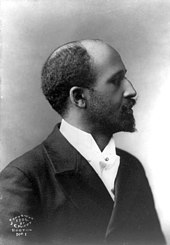

W. E. B. Du Bois | |

|---|---|

Portrait by James E. Purdy, 1907 | |

| Signature | |

| |

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (/djuːˈbɔɪs/ dew-BOYSS; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relatively tolerant and integrated community. After completing graduate work at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin and Harvard University, where he was its first African American to earn a doctorate, Du Bois rose to national prominence as a leader of the Niagara Movement, a group of black civil rights activists seeking equal rights. Du Bois and his supporters opposed the Atlanta Compromise. Instead, Du Bois insisted on full civil rights and increased political representation, which he believed would be brought about by the African-American intellectual elite. He referred to this group as the Talented Tenth, a concept under the umbrella of racial uplift, and believed that African Americans needed the chances for advanced education to develop its leadership.

Du Bois was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. Du Bois used his position in the NAACP to respond to racist incidents. After the First World War, he attended the Pan-African Congresses, embraced socialism and became a professor at Atlanta University. Once the Second World War had ended, he engaged in peace activism and was targeted by the FBI. He spent the last years of his life in Ghana and died in Accra on August 27, 1963.

Du Bois was a prolific author. Du Bois primarily targeted racism in his polemics, which protested strongly against lynching, Jim Crow laws, and discrimination in education and employment. His cause included people of color everywhere, particularly Africans and Asians in colonies. He was a proponent of Pan-Africanism and helped organize several Pan-African Congresses to fight for the independence of African colonies from European powers. Du Bois made several trips to Europe, Africa and Asia. His collection of essays, The Souls of Black Folk, is a seminal work in African-American literature; and his 1935 magnum opus, Black Reconstruction in America, challenged the prevailing orthodoxy that blacks were responsible for the failures of the Reconstruction era. Borrowing a phrase from Frederick Douglass, he popularized the use of the term color line to represent the injustice of the separate but equal doctrine prevalent in American social and political life. His 1940 autobiography Dusk of Dawn is regarded in part as one of the first scientific treatises in the field of American sociology. In his role as editor of the NAACP's journal The Crisis, he published many influential pieces. Du Bois believed that capitalism was a primary cause of racism and was sympathetic to socialist causes.

Early life

Family and childhood

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born on February 23, 1868, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, to Alfred and Mary Silvina Burghardt Du Bois. Mary Silvina Burghardt's family was part of the very small free black population of Great Barrington and had long owned land in the state. She was descended from Dutch, African, and English ancestors. William Du Bois's maternal great-great-grandfather was Tom Burghardt, a slave (born in West Africa around 1730) who was held by the Dutch colonist Conraed Burghardt. Tom briefly served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, which may have been how he gained his freedom during the late 18th century. His son Jack Burghardt was the father of Othello Burghardt, who in turn was the father of Mary Silvina Burghardt.

William Du Bois claimed Elizabeth Freeman as his relative; he wrote that she had married his great-grandfather Jack Burghardt. But Freeman was 20 years older than Burghardt, and no record of such a marriage has been found. It may have been Freeman's daughter, Betsy Humphrey, who married Burghardt after her first husband, Jonah Humphrey, left the area "around 1811", and after Burghardt's first wife died (c. 1810). If so, Freeman would have been William Du Bois's step-great-great-grandmother. Anecdotal evidence supports Humphrey's marrying Burghardt; a close relationship of some form is likely.

William Du Bois's paternal great-grandfather was James Du Bois of Poughkeepsie, New York, an ethnic French-American of Huguenot origin who fathered several children with slave women. One of James' mixed-race sons was Alexander, who was born on Long Cay in the Bahamas in 1803; in 1810, he immigrated to the United States with his father. Alexander Du Bois traveled and worked in Haiti, where he fathered a son, Alfred, with a mistress. Alexander returned to Connecticut, leaving Alfred in Haiti with his mother.

Sometime before 1860, Alfred Du Bois immigrated to the United States, settling in Massachusetts. He married Mary Silvina Burghardt on February 5, 1867, in Housatonic, a village in Great Barrington. Alfred left Mary in 1870, two years after their son William was born. Mary Du Bois moved with her son back to her parents' house in Great Barrington, and they lived there until he was five. She worked to support her family (receiving some assistance from her brother and neighbors), until she suffered a stroke in the early 1880s. She died in 1885.

Great Barrington had a majority European American community, who generally treated Du Bois well. He attended the local integrated public school and played with white schoolmates. As an adult, he wrote about racism that he felt as a fatherless child and being a minority in the town. But teachers recognized his ability and encouraged his intellectual pursuits, and his rewarding experience with academic studies led him to believe that he could use his knowledge to empower African Americans. In 1884, he graduated from the town's Great Barrington High School with honors. When he decided to attend college, the congregation of his childhood church, the First Congregational Church of Great Barrington, raised the money for his tuition.

University education

Relying on this money donated by neighbors, Du Bois attended Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee, from 1885 to 1888. Like other Fisk students who relied on summer and intermittent teaching to support their university studies, Du Bois taught school during the summer of 1886 after his sophomore year. His travel to and residency in the South was Du Bois's first experience with Southern racism, which at the time encompassed Jim Crow laws, bigotry, suppression of black voting, and lynchings; the lattermost reached a peak in the next decade.

After receiving a bachelor's degree from Fisk, he attended Harvard College (which did not accept course credits from Fisk) from 1888 to 1890, where he was strongly influenced by professor William James, prominent in American philosophy. Du Bois paid his way through three years at Harvard with money from summer jobs, an inheritance, scholarships, and loans from friends. In 1890, Harvard awarded Du Bois his second bachelor's degree, cum laude, in history. In 1891, Du Bois received a scholarship to attend the sociology graduate school at Harvard.

In 1892, Du Bois received a fellowship from the John F. Slater Fund for the Education of Freedmen to attend the Friedrich Wilhelm University for graduate work. While a student in Berlin, he traveled extensively throughout Europe. He came of age intellectually in the German capital while studying with some of that nation's most prominent social scientists, including Gustav von Schmoller, Adolph Wagner, and Heinrich von Treitschke. He also met Max Weber who was highly impressed with Du Bois and later cited Du Bois as a counter-example to racists alleging the inferiority of Blacks. Weber met Du Bois again in 1904 on a visit to the US just ahead of the publication of the seminal The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

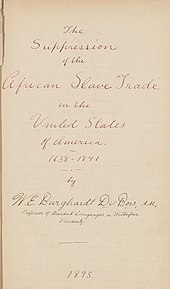

He wrote about his time in Germany: "I found myself on the outside of the American world, looking in. With me were white folk – students, acquaintances, teachers – who viewed the scene with me. They did not always pause to regard me as a curiosity, or something sub-human; I was just a man of the somewhat privileged student rank, with whom they were glad to meet and talk over the world; particularly, the part of the world whence I came." After returning from Europe, Du Bois completed his graduate studies; in 1895, he was the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University.

Wilberforce

Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: ... How does it feel to be a problem? ... One ever feels his two-ness, – an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder ... He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face.

—Du Bois, "Strivings of the Negro People", 1897

In the summer of 1894, Du Bois received several job offers, including from Tuskegee Institute; he accepted a teaching job at Wilberforce University in Ohio. At Wilberforce, Du Bois was strongly influenced by Alexander Crummell, who believed that ideas and morals are necessary tools to effect social change. While at Wilberforce, Du Bois married Nina Gomer, one of his students, on May 12, 1896.

Philadelphia

After two years at Wilberforce, Du Bois accepted a one-year research job from the University of Pennsylvania as an "assistant in sociology" in the summer of 1896. He performed sociological field research in Philadelphia's African-American neighborhoods, which formed the foundation for his landmark study, The Philadelphia Negro, published in 1899 while he was teaching at Atlanta University. It was the first case study of a black community in the United States. Among his Philadelphia consultants on the project was William Henry Dorsey, an artist who collected documents, paintings and artifact pertaining to Black history. Dorsey compiled hundreds of scrapbooks on the lives of Black people during the 19th century and built a collection that he laid out in his home in Philadelphia. Du Bois used the scrapbooks in his research.

By the 1890s, Philadelphia's black neighborhoods had a negative reputation in terms of crime, poverty, and mortality. Du Bois's book undermined the stereotypes with empirical evidence and shaped his approach to segregation and its negative impact on black lives and reputations. The results led him to realize that racial integration was the key to democratic equality in American cities. The methodology employed in The Philadelphia Negro, namely the description and the mapping of social characteristics onto neighborhood areas was a forerunner to the studies under the Chicago School of Sociology.

While taking part in the American Negro Academy (ANA) in 1897, Du Bois presented a paper in which he rejected Frederick Douglass's plea for black Americans to integrate into white society. He wrote: "we are Negroes, members of a vast historic race that from the very dawn of creation has slept, but half awakening in the dark forests of its African fatherland". In the August 1897 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, Du Bois published "Strivings of the Negro People", his first work aimed at the general public, in which he enlarged upon his thesis that African Americans should embrace their African heritage while contributing to American society.

Atlanta University

In July 1897, Du Bois left Philadelphia and took a professorship in history and economics at the historically black Atlanta University in Georgia. His first major academic work was his book The Philadelphia Negro (1899), a detailed and comprehensive sociological study of the African-American people of Philadelphia, based on his fieldwork in 1896–1897. This breakthrough in scholarship was the first scientific study of African Americans and a major contribution to early scientific sociology in the U.S.

Du Bois coined the phrase "the submerged tenth" to describe the black underclass in the study. Later in 1903, he popularized the term, the "Talented tenth", applied to society's elite class. His terminology reflected his opinion that the elite of a nation, both black and white, were critical to achievements in culture and progress. During this period he wrote dismissively of the underclass, describing them as "lazy" or "unreliable", but – in contrast to other scholars – he attributed many of their societal problems to the ravages of slavery.

Du Bois's output at Atlanta University was prodigious, in spite of a limited budget: he produced numerous social science papers and annually hosted the Atlanta Conference of Negro Problems. He also received grants from the U.S. government to prepare reports about African-American workforce and culture. His students considered him to be a teacher that was brilliant, but aloof and strict.

First Pan-African Conference

Du Bois attended the First Pan-African Conference, held in London on July 23–25, 1900, shortly ahead of the Paris Exhibition of 1900 ("to allow tourists of African descent to attend both events".) The Conference had been organized by people from the Caribbean: Haitians Anténor Firmin and Benito Sylvain and Trinidadian barrister Henry Sylvester Williams. Du Bois played a leading role in drafting a letter ("Address to the Nations of the World"), asking European leaders to struggle against racism, to grant colonies in Africa and the West Indies the right to self-government and to demand political and other rights for African Americans. By this time, southern states were passing new laws and constitutions to disfranchise most African Americans, an exclusion from the political system that lasted into the 1960s.

At the conclusion of the conference, delegates unanimously adopted the "Address to the Nations of the World", and sent it to various heads of state where people of African descent were living and suffering oppression. The address implored the United States and the imperial European nations to "acknowledge and protect the rights of people of African descent" and to respect the integrity and independence of "the free Negro States of Abyssinia, Liberia, Haiti, etc." It was signed by Bishop Alexander Walters (President of the Pan-African Association), the Canadian Rev. Henry B. Brown (vice-president), Williams (General Secretary) and Du Bois (chairman of the committee on the Address). The address included Du Bois's observation, "The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the colour-line." He used this again three years later in the "Forethought" of his book The Souls of Black Folk (1903).

1900 Paris Exposition

Du Bois was the primary organizer of The Exhibit of American Negroes at the Exposition Universelle held in Paris between April and November 1900, for which he put together a series of 363 photographs aiming to commemorate the lives of African Americans at the turn of the century and challenge the racist caricatures and stereotypes of the day. Also included were charts, graphs, and maps. He was awarded a gold medal for his role as compiler of the materials, which are now housed at the Library of Congress.

Booker T. Washington and the Atlanta Compromise

In the first decade of the new century, Du Bois emerged as a spokesperson for his race, second only to Booker T. Washington. Washington was the director of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, and wielded tremendous influence within the African-American and white communities. Washington was the architect of the Atlanta Compromise, an unwritten deal that he had struck in 1895 with Southern white leaders who dominated state governments after Reconstruction. Essentially the agreement provided that Southern blacks, who overwhelmingly lived in rural communities, would submit to the current discrimination, segregation, disenfranchisement, and non-unionized employment; that Southern whites would permit blacks to receive a basic education, some economic opportunities, and justice within the legal system; and that Northern whites would invest in Southern enterprises and fund black educational charities.

Despite initially sending congratulations to Washington for his Atlanta Exposition Speech, Du Bois later came to oppose Washington's plan, along with many other African Americans, including Archibald H. Grimke, Kelly Miller, James Weldon Johnson, and Paul Laurence Dunbar – representatives of the class of educated blacks that Du Bois would later call the "talented tenth". Du Bois felt that African Americans should fight for equal rights and higher opportunities, rather than passively submit to the segregation and discrimination of Washington's Atlanta Compromise.

Du Bois was inspired to greater activism by the lynching of Sam Hose, which occurred near Atlanta in 1899. Hose was tortured, burned, and hanged by a mob of two thousand whites. When walking through Atlanta to discuss the lynching with newspaper editor Joel Chandler Harris, Du Bois encountered Hose's burned knuckles in a storefront display. The episode stunned Du Bois, and he resolved that "one could not be a calm, cool, and detached scientist while Negroes were lynched, murdered, and starved". Du Bois realized that "the cure wasn't simply telling people the truth, it was inducing them to act on the truth".

In 1901, Du Bois wrote a review critical of Washington's autobiography Up from Slavery, which he later expanded and published to a wider audience as the essay "Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others" in The Souls of Black Folk. Later in life, Du Bois regretted having been critical of Washington in those essays. One of the contrasts between the two leaders was their approach to education: Washington felt that African-American schools should focus primarily on industrial education topics such as agricultural and mechanical skills, to prepare southern blacks for the opportunities in the rural areas where most lived. Du Bois felt that black schools should focus more on liberal arts and academic curriculum (including the classics, arts, and humanities), because liberal arts were required to develop a leadership elite.

However, as sociologist E. Franklin Frazier and economists Gunnar Myrdal and Thomas Sowell have argued, such disagreement over education was a minor point of difference between Washington and Du Bois; both men acknowledged the importance of the form of education that the other emphasized. Sowell has also argued that, despite genuine disagreements between the two leaders, the supposed animosity between Washington and Du Bois actually formed among their followers, not between Washington and Du Bois themselves. Du Bois also made this observation in an interview published in The Atlantic Monthly in November 1965.

Niagara Movement

In 1905, Du Bois and several other African-American civil rights activists – including Fredrick McGhee, Max Barber and William Monroe Trotter – met in Canada, near Niagara Falls, where they wrote a declaration of principles opposing the Atlanta Compromise, and which were incorporated as the Niagara Movement in 1906. They wanted to publicize their ideals to other African Americans, but most black periodicals were owned by publishers sympathetic to Washington, so Du Bois bought a printing press and started publishing Moon Illustrated Weekly in December 1905. It was the first African-American illustrated weekly, and Du Bois used it to attack Washington's positions, but the magazine lasted only for about eight months. Du Bois soon founded and edited another vehicle for his polemics, The Horizon: A Journal of the Color Line, which debuted in 1907. Freeman H. M. Murray and Lafayette M. Hershaw served as The Horizon's co-editors.

The Niagarites held a second conference in August 1906, in celebration of the 100th anniversary of abolitionist John Brown's birth, at the West Virginia site of Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry. Reverdy C. Ransom spoke, explaining that Washington's primary goal was to prepare blacks for employment in their current society: "Today, two classes of Negroes ...are standing at the parting of the ways. The one counsels patient submission to our present humiliations and degradations ... The other class believe that it should not submit to being humiliated, degraded, and remanded to an inferior place. ...[I]t does not believe in bartering its manhood for the sake of gain."

The Souls of Black Folk

In an effort to portray the genius and humanity of the black race, Du Bois published The Souls of Black Folk (1903), a collection of 14 essays. James Weldon Johnson said the book's effect on African Americans was comparable to that of Uncle Tom's Cabin. The introduction famously proclaimed that "the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line". Each chapter begins with two epigraphs – one from a white poet, and one from a black spiritual – to demonstrate intellectual and cultural parity between black and white cultures.

A major theme of the work was the double consciousness faced by African Americans: being both American and black. This was a unique identity which, according to Du Bois, had been a handicap in the past, but could be a strength in the future: "Henceforth, the destiny of the race could be conceived as leading neither to assimilation nor separatism but to proud, enduring hyphenation."

Jonathon S. Kahn in Divine Discontent: The Religious Imagination of Du Bois shows how Du Bois, in his The Souls of Black Folk, represents an exemplary text of pragmatic religious naturalism. On page 12, Kahn writes: "Du Bois needs to be understood as an African American pragmatic religious naturalist. By this I mean that, like Du Bois the American traditional pragmatic religious naturalism, which runs through William James, George Santayana, and John Dewey, seeks religion without metaphysical foundations." Kahn's interpretation of religious naturalism is very broad but he relates it to specific thinkers. Du Bois's anti-metaphysical viewpoint places him in the sphere of religious naturalism as typified by William James and others.

Racial violence

Two calamities in the autumn of 1906 shocked African Americans, and they contributed to strengthening support for Du Bois's struggle for civil rights to prevail over Booker T. Washington's accommodationism. First, President Theodore Roosevelt dishonorably discharged 167 Buffalo Soldiers because they were accused of crimes as a result of the Brownsville affair. Many of the discharged soldiers had served for 20 years and were near retirement. Second, in September, riots broke out in Atlanta, precipitated by unfounded allegations of black men assaulting white women. This was a catalyst for racial tensions based on a job shortage and employers playing black workers against white workers. Ten thousand whites rampaged through Atlanta, beating every black person they could find, resulting in over 25 deaths. In the aftermath of the 1906 violence, Du Bois urged blacks to withdraw their support from the Republican Party, because Republicans Roosevelt and William Howard Taft did not sufficiently support blacks. Most African Americans had been loyal to the Republican Party since the time of Abraham Lincoln. Du Bois endorsed Taft's rival William Jennings Bryan in the 1908 presidential election despite Bryan's acceptance of segregation.

Du Bois wrote the essay, "A Litany at Atlanta", which asserted that the riot demonstrated that the Atlanta Compromise was a failure. Despite upholding their end of the bargain, blacks had failed to receive legal justice in the South. Historian David Levering Lewis has written that the Compromise no longer held because white patrician planters, who took a paternalistic role, had been replaced by aggressive businessmen who were willing to pit blacks against whites. These two calamities were watershed events for the African American community, marking the ascendancy of Du Bois's vision of equal rights.

Academic work

Once we were told: Be worthy and fit and the ways are open. Today, the avenues of advancement in the army, navy, civil service, and even business and professional life are continually closed to black applicants of proven fitness, simply on the bald excuse of race and color.

—Du Bois, "Address at Fourth Niagara Conference", 1908

In addition to writing editorials, Du Bois continued to produce scholarly work at Atlanta University. In 1909, after five years of effort, he published a biography of abolitionist John Brown. It contained many insights, but also contained some factual errors. The work was strongly criticized by The Nation, which was owned by Oswald Garrison Villard, who was writing his own, competing biography of John Brown. Possibly as a result, Du Bois's work was largely ignored by white scholars. After publishing a piece in Collier's magazine warning of the end of "white supremacy", Du Bois had difficulty getting pieces accepted by major periodicals, although he did continue to publish columns regularly in The Horizon magazine.

Du Bois was the first African American invited by the American Historical Association (AHA) to present a paper at their annual conference. He read his paper, Reconstruction and Its Benefits, to an astounded audience at the AHA's December 1909 conference. The paper went against the mainstream historical view, promoted by the Dunning School of scholars at Columbia University, that Reconstruction was a disaster, caused by the ineptitude and sloth of blacks. To the contrary, Du Bois asserted that the brief period of African-American leadership in the South accomplished three important goals: democracy, free public schools, and new social welfare legislation.

Du Bois asserted that it was the federal government's failure to manage the Freedmen's Bureau, to distribute land, and to establish an educational system, that doomed African-American prospects in the South. When Du Bois submitted the paper for publication a few months later in The American Historical Review, he asked that the word 'Negro' be capitalized. The editor, J. Franklin Jameson, refused, and published the paper without the capitalization. The paper was mostly ignored by white historians. Du Bois later developed his paper as his 1935 book, Black Reconstruction in America, which marshaled extensive references to support his assertions. The AHA did not invite another African-American speaker until 1940.

NAACP era

In May 1909, Du Bois attended the National Negro Conference in New York. The meeting led to the creation of the National Negro Committee, chaired by Oswald Garrison Villard, and dedicated to campaigning for civil rights, equal voting rights, and equal educational opportunities. The following spring, in 1910, at the second National Negro Conference, the attendees created the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). At Du Bois's suggestion, the word "colored", rather than "black", was used to include "dark skinned people everywhere". Dozens of civil rights supporters, black and white, participated in the founding, but most executive officers were white, including Mary White Ovington, Charles Edward Russell, William English Walling, and its first president, Moorfield Storey.

Feeling inspired by this, Indian social reformer and civil rights activist B. R. Ambedkar contacted Du Bois in the 1940s. In a letter to Du Bois in 1946, he introduced himself as a member of the "Untouchables of India" and "a student of the Negro problem" and expressed his interest in the NAACP's petition to the United Nations. He noted that his group was "thinking of following suit"; and requested copies of the proposed statement from Du Bois. In a letter dated July 31, 1946, Du Bois responded by telling Ambedkar he was familiar with his name, and that he had "every sympathy with the Untouchables of India."

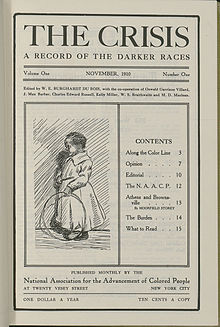

The Crisis

NAACP leaders offered Du Bois the position of Director of Publicity and Research. He accepted the job in the summer of 1910, and moved to New York after resigning from Atlanta University. His primary duty was editing the NAACP's monthly magazine, which he named The Crisis. The first issue appeared in November 1910, and Du Bois wrote that its aim was to set out "those facts and arguments which show the danger of race prejudice, particularly as manifested today toward colored people". The journal was phenomenally successful, and its circulation would reach 100,000 in 1920. Typical articles in the early editions polemics against the dishonesty and parochialism of black churches, and discussions on the Afrocentric origins of Egyptian civilization. Du Bois's African-centered view of ancient Egypt was in direct opposition to many Egyptologists of his day, including Flinders Petrie, whom Du Bois had met a conference.

A 1911 Du Bois editorial helped initiate a nationwide push to induce the federal government to outlaw lynching. Du Bois, employing the sarcasm he frequently used, commented on a lynching in Pennsylvania: "The point is he was black. Blackness must be punished. Blackness is the crime of crimes ... It is therefore necessary, as every white scoundrel in the nation knows, to let slip no opportunity of punishing this crime of crimes. Of course if possible, the pretext should be great and overwhelming – some awful stunning crime, made even more horrible by the reporters' imagination. Failing this, mere murder, arson, barn burning or impudence may do."

The Crisis carried Du Bois editorials supporting the ideals of unionized labor but denouncing its leaders' racism; blacks were barred from membership. Du Bois also supported the principles of the Socialist Party of America (he held party membership from 1910 to 1912), but he denounced the racism demonstrated by some socialist leaders. Frustrated by Republican president Taft's failure to address widespread lynching, Du Bois endorsed Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson in the 1912 presidential race, in exchange for Wilson's promise to support black causes.

Throughout his writings, Du Bois supported women's rights and women's suffrage, but he found it difficult to publicly endorse the women's right-to-vote movement because leaders of the suffragism movement refused to support his fight against racial injustice. A 1913 Crisis editorial broached the taboo subject of interracial marriage: although Du Bois generally expected persons to marry within their race, he viewed the problem as a women's rights issue, because laws prohibited white men from marrying black women. Du Bois wrote "[anti-miscegenation] laws leave the colored girls absolutely helpless for the lust of white men. It reduces colored women in the eyes of the law to the position of dogs. As low as the white girl falls, she can compel her seducer to marry her ... We must kill [anti-miscegenation laws] not because we are anxious to marry the white men's sisters, but because we are determined that white men will leave our sisters alone."

During 1915−1916, some leaders of the NAACP – disturbed by financial losses at The Crisis, and worried about the inflammatory rhetoric of some of its essays – attempted to oust Du Bois from his editorial position. Du Bois and his supporters prevailed, and he continued in his role as editor. In a 1919 column titled "The True Brownies", he announced the creation of The Brownies' Book, the first magazine published for African-American children and youth, which he founded with Augustus Granville Dill and Jessie Redmon Fauset.

Historian and author

The 1910s were a productive time for Du Bois. In 1911, he attended the First Universal Races Congress in London and he published his first novel, The Quest of the Silver Fleece. Two years later, Du Bois wrote, produced, and directed a pageant for the stage, The Star of Ethiopia. In 1915, Du Bois published The Negro, a general history of black Africans, and the first of its kind in English. The book rebutted claims of African inferiority, and would come to serve as the basis of much Afrocentric historiography in the 20th century. The Negro predicted unity and solidarity for colored people around the world, and it influenced many who supported the Pan-African movement.

In 1915, The Atlantic Monthly carried a Du Bois essay, "The African Roots of the War", which consolidated his ideas on capitalism, imperialism, and race. He argued that the Scramble for Africa was at the root of World War I. He also anticipated later communist doctrine, by suggesting that wealthy capitalists had pacified white workers by giving them just enough wealth to prevent them from revolting, and by threatening them with competition by the lower-cost labor of colored workers.

Combating racism

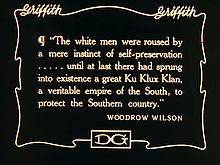

Du Bois used his influential NAACP position to oppose a variety of racist incidents. When the silent film The Birth of a Nation premiered in 1915, Du Bois and the NAACP led the fight to ban the movie, because of its racist portrayal of blacks as brutish and lustful. The fight was not successful, and possibly contributed to the film's fame, but the publicity drew many new supporters to the NAACP.

The private sector was not the only source of racism: under President Wilson, the plight of African Americans in government jobs suffered. Many federal agencies adopted whites-only employment practices, the Army excluded blacks from officer ranks, and the immigration service prohibited the immigration of persons of African ancestry. Du Bois wrote an editorial in 1914 deploring the dismissal of blacks from federal posts, and he supported William Monroe Trotter when Trotter brusquely confronted Wilson about the President's failure to fulfill his campaign promise of justice for blacks.

The Crisis continued to wage a campaign against lynching. In 1915, it published an article with a year-by-year tabulation of 2,732 lynchings from 1884 to 1914. The April 1916 edition covered the group lynching of six African Americans in Lee County, Georgia. Later in the June 1916 issue, the "Waco Horror" article covered the lynching of Jesse Washington, a mentally impaired 17-year-old African American. Du Bois included photographs of it in the article. The article broke new ground by utilizing undercover reporting to expose the conduct of local whites in Waco, Texas.

The early 20th century was the era of the Great Migration of blacks from the Southern United States to the Northeast, Midwest, and West. Du Bois wrote an editorial supporting the Great Migration, because he felt it would help blacks escape Southern racism, find economic opportunities, and assimilate into American society.

Also in the 1910s the American eugenics movement was in its infancy, and many leading eugenicists were openly racist, defining Blacks as "a lower race". Du Bois opposed this view as an unscientific aberration, but still maintained the basic principle of eugenics: that different persons have different inborn characteristics that make them more or less suited for specific kinds of employment, and that by encouraging the most talented members of all races to procreate would better the "stocks" of humanity.

World War I

As the United States prepared to enter World War I in 1917, Du Bois's colleague in the NAACP, Joel Spingarn, established a camp to train African Americans to serve as officers in the United States Armed Forces. The camp was controversial, because some whites felt that blacks were not qualified to be officers, and some blacks felt that African Americans should not participate in what they considered a white man's war. Du Bois supported Spingarn's training camp, but was disappointed when the Army forcibly retired one of its few black officers, Charles Young, on a pretense of ill health. The Army agreed to create 1,000 officer positions for blacks, but insisted that 250 come from enlisted men, conditioned to taking orders from whites, rather than from independent-minded blacks who came from the camp. Over 700,000 blacks enlisted on the first day of the draft, but were subject to discriminatory conditions which prompted vocal protests from Du Bois.

After the East St. Louis riots occurred in the summer of 1917, Du Bois traveled to St. Louis to report on the riots. Between 40 and 250 African Americans were massacred by whites, primarily due to resentment caused by St. Louis industry hiring blacks to replace striking white workers. Du Bois's reporting resulted in an article "The Massacre of East St. Louis", published in the September issue of The Crisis, which contained photographs and interviews detailing the violence. Historian David Levering Lewis concluded that Du Bois distorted some of the facts in order to increase the propaganda value of the article. To publicly demonstrate the black community's outrage over the riots, Du Bois organized the Silent Parade, a march of around 9,000 African Americans down New York City's Fifth Avenue, the first parade of its kind in New York, and the second instance of blacks publicly demonstrating for civil rights.

The Houston riot of 1917 disturbed Du Bois and was a major setback to efforts to permit African Americans to become military officers. The riot began after Houston police arrested and beat two black soldiers; in response, over 100 black soldiers took to the streets of Houston and killed 16 whites. A military court martial was held, and 19 of the soldiers were hanged, and 67 others were imprisoned. In spite of the Houston riot, Du Bois and others successfully pressed the Army to accept the officers trained at Spingarn's camp, resulting in over 600 black officers joining the Army in October 1917.

Federal officials, concerned about subversive viewpoints expressed by NAACP leaders, attempted to frighten the NAACP by threatening it with investigations. Du Bois was not intimidated, and in 1918 he predicted that World War I would lead to an overthrow of the European colonial system and to the "liberation" of colored people worldwide – in China, in India, and especially in the Americas. NAACP chairman Joel Spingarn was enthusiastic about the war, and he persuaded Du Bois to consider an officer's commission in the Army, contingent on Du Bois writing an editorial repudiating his anti-war stance. Du Bois accepted this bargain and wrote the pro-war "Close Ranks" editorial in June 1918 and soon thereafter he received a commission in the Army. Many black leaders, who wanted to leverage the war to gain civil rights for African Americans, criticized Du Bois for his sudden reversal. Southern officers in Du Bois's unit objected to his presence, and his commission was withdrawn.

After the war

When the war ended, Du Bois traveled to Europe in 1919 to attend the first Pan-African Congress and to interview African-American soldiers for a planned book on their experiences in World War I. He was trailed by U.S. agents who were searching for evidence of treasonous activities. Du Bois discovered that the vast majority of black American soldiers were relegated to menial labor as stevedores and laborers. Some units were armed, and one in particular, the 92nd Division (the Buffalo soldiers), engaged in combat. Du Bois discovered widespread racism in the Army, and concluded that the Army command discouraged African Americans from joining the Army, discredited the accomplishments of black soldiers, and promoted bigotry.

Du Bois returned from Europe more determined than ever to gain equal rights for African Americans. Black soldiers returning from overseas felt a new sense of power and worth, and were representative of an emerging attitude referred to as the New Negro. In the editorial "Returning Soldiers" he wrote: "But, by the God of Heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if, now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land."

Many blacks moved to northern cities in search of work, and some northern white workers resented the competition. This labor strife was one of the causes of the Red Summer, a series of race riots across America in 1919, in which over 300 African Americans were killed in over 30 cities. Du Bois documented the atrocities in the pages of The Crisis, culminating in the December publication of a gruesome photograph of a lynching that occurred during a race riot in Omaha, Nebraska.

The most violent episode during the Red Summer was a massacre in Elaine, Arkansas in which nearly 200 blacks were murdered. Reports coming out of the South blamed the blacks, alleging that they were conspiring to take over the government. Infuriated with the distortions, Du Bois published a letter in the New York World, claiming that the only crime the black sharecroppers had committed was daring to challenge their white landlords by hiring an attorney to investigate contractual irregularities.

Over 60 of the surviving blacks were arrested and tried for conspiracy, in the case known as Moore v. Dempsey. Du Bois rallied blacks across America to raise funds for the legal defense, which, six years later, resulted in a Supreme Court ruling authored by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Although the victory had little immediate impact on justice for blacks in the South, it marked the first time the federal government used the 14th Amendment guarantee of due process to prevent states from shielding mob violence.

In 1920, Du Bois published Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil, the first of his three autobiographies. The "veil" was that which covered colored people around the world. In the book, he hoped to lift the veil and show white readers what life was like behind the veil, and how it distorted the viewpoints of those looking through it – in both directions. The book contained Du Bois's feminist essay, "The Damnation of Women", which was a tribute to the dignity and worth of women, particularly black women.

Concerned that textbooks used by African-American children ignored black history and culture, Du Bois created a monthly children's magazine, The Brownies' Book. Initially published in 1920, it was aimed at black children, who Du Bois called "the children of the sun".

Pan-Africanism and Marcus Garvey

Du Bois traveled to Europe in 1921 to attend the second Pan-African Congress. The assembled black leaders from around the world issued the London Resolutions and established a Pan-African Association headquarters in Paris. Under Du Bois's guidance, the resolutions insisted on racial equality, and that Africa be ruled by Africans (not, as in the 1919 congress, with the consent of Africans).[190] Du Bois restated the resolutions of the congress in his Manifesto to the League of Nations, which implored the newly formed League of Nations to address labor issues and to appoint Africans to key posts. The League took little action on the requests.

Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey, promoter of the Back-to-Africa movement and founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), denounced Du Bois's efforts to achieve equality through integration, and instead endorsed racial separatism. Du Bois initially supported the concept of Garvey's Black Star Line, a shipping company that was intended to facilitate commerce within the African diaspora. But Du Bois later became concerned that Garvey was threatening the NAACP's efforts, leading Du Bois to describe him as fraudulent and reckless. Responding to Garvey's slogan "Africa for the Africans", Du Bois said that he supported that concept, but denounced Garvey's intention that Africa be ruled by African Americans.

Du Bois wrote a series of articles in The Crisis between 1922 and 1924 attacking Garvey's movement, calling him the "most dangerous enemy of the Negro race in America and the world." Du Bois and Garvey never made a serious attempt to collaborate, and their dispute was partly rooted in the desire of their respective organizations (NAACP and UNIA) to capture a larger portion of the available philanthropic funding.

Du Bois decried Harvard's decision to ban blacks from its dormitories in 1921 as an instance of a broad effort in the U.S. to renew "the Anglo-Saxon cult; the worship of the Nordic totem, the disfranchisement of Negro, Jew, Irishman, Italian, Hungarian, Asiatic and South Sea Islander – the world rule of Nordic white through brute force." When Du Bois sailed for Europe in 1923 for the third Pan-African Congress, the circulation of The Crisis had declined to 60,000 from its World War I high of 100,000, but it remained the preeminent periodical of the civil rights movement. President Calvin Coolidge designated Du Bois an "Envoy Extraordinary" to Liberia and – after the third congress concluded – Du Bois rode a German freighter from the Canary Islands to Africa, visiting Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Senegal.

Harlem Renaissance

Du Bois frequently promoted African-American artistic creativity in his writings, and when the Harlem Renaissance emerged in the mid-1920s, his article "A Negro Art Renaissance" celebrated the end of the long hiatus of blacks from creative endeavors. His enthusiasm for the Harlem Renaissance waned as he came to believe that many whites visited Harlem for voyeurism, not for genuine appreciation of black art. Du Bois insisted that artists recognize their moral responsibilities, writing that "a black artist is first of all a black artist." He was also concerned that black artists were not using their art to promote black causes, saying "I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda." By the end of 1926, he stopped employing The Crisis to support the arts.

Debate with Lothrop Stoddard

In 1929, a debate organised by the Chicago Forum Council billed as "One of the greatest debates ever held" was held between Du Bois and Lothrop Stoddard, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, proponent of eugenics and so-called scientific racism. The debate was held in Chicago and Du Bois was arguing the affirmative to the question "Shall the Negro be encouraged to seek cultural equality? Has the Negro the same intellectual possibilities as other races?"

Du Bois knew that the racists would be unintentionally funny onstage; as he wrote to Moore, Senator J. Thomas Heflin "would be a scream" in a debate. Du Bois let the overconfident and bombastic Stoddard walk into a comic moment, which Stoddard then made even funnier by not getting the joke. This moment was captured in headlines "DuBois Shatters Stoddard's Cultural Theories in Debate; Thousands Jam Hall ... Cheered as He Proves Race Equality," The Chicago Defender's front-page headline ran "5,000 Cheer W.E.B. DuBois, Laugh at Lothrop Stoddard". Ian Frazier of The New Yorker wrotes that the comic potential of Stoddard's bankrupt ideas was left untapped until Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove.

Socialism

When Du Bois became editor of The Crisis magazine in 1911, he joined the Socialist Party of America on the advice of NAACP founders Mary White Ovington, William English Walling and Charles Edward Russell. However, he supported the Democrat Woodrow Wilson in the 1912 presidential campaign, a breach of the rules, and was forced to resign from the Socialist Party. In 1913, his support for Wilson was shaken when racial segregation in government hiring was reported. Du Bois remained "convinced that socialism was an excellent way of life, but I thought it might be reached by various methods."

Nine years after the 1917 Russian Revolution, Du Bois extended a trip to Europe to include a visit to the Soviet Union, where he was struck by the poverty and disorganization he encountered in the Soviet Union, yet was impressed by the intense labors of the officials and by the recognition given to workers. Although Du Bois was not yet familiar with the communist theories of Karl Marx or Vladimir Lenin, he concluded that socialism might be a better path towards racial equality than capitalism.

Although Du Bois generally endorsed socialist principles, his politics were strictly pragmatic: in the 1929 New York City mayoral election, he endorsed Democrat Jimmy Walker for mayor of New York, rather than the socialist Norman Thomas, believing that Walker could do more immediate good for blacks, even though Thomas's platform was more consistent with Du Bois's views. Throughout the 1920s, Du Bois and the NAACP shifted support back and forth between the Republican Party and the Democratic Party, induced by promises from the candidates to fight lynchings, improve working conditions, or support voting rights in the South; invariably, the candidates failed to deliver on their promises.

And herein lies the tragedy of the age: not that men are poor – all men know something of poverty; not that men are wicked – who is good? Not that men are ignorant – what is Truth? Nay, but that men know so little of men.

—Du Bois, "Of Alexander Crummell", in The Souls of Black Folk, 1903

A rivalry emerged in 1931 between the NAACP and the Communist Party, when the communists responded quickly and effectively to support the Scottsboro Boys, nine African American youth arrested in 1931 in Alabama for rape. Du Bois and the NAACP felt that the case would not be beneficial to their cause, so they chose to let the Communist Party organize the defense efforts. Du Bois was impressed with the vast amount of publicity and funds which the communists devoted to the partially successful defense effort, and he came to suspect that the communists were attempting to present their party to African Americans as a better solution than the NAACP.

Responding to criticisms of the NAACP from the Communist Party, Du Bois wrote articles condemning the party, claiming that it unfairly attacked the NAACP, and that it failed to fully appreciate racism in the United States. In their turn, the communist leaders accused him of being a "class enemy", and claimed that the NAACP leadership was an isolated elite, disconnected from the working-class blacks they ostensibly fought for.

Return to Atlanta

Du Bois did not have a good working relationship with Walter White, president of the NAACP since 1931. That conflict, combined with the financial stresses of the Great Depression, precipitated a power struggle over The Crisis. Du Bois, concerned that his position as editor would be eliminated, resigned his job at The Crisis and accepted an academic position at Atlanta University in early 1933. The rift with the NAACP grew larger in 1934 when Du Bois reversed his stance on segregation, stating that "separate but equal" was an acceptable goal for African Americans. The NAACP leadership was stunned, and asked Du Bois to retract his statement, but he refused, and the dispute led to Du Bois's resignation from the NAACP.

After arriving at his new professorship in Atlanta, Du Bois wrote a series of articles generally supportive of Marxism. He was not a strong proponent of labor unions or the Communist Party, but he felt that Marx's scientific explanation of society and the economy were useful for explaining the situation of African Americans in the United States. Marx's atheism also struck a chord with Du Bois, who routinely criticized black churches for dulling blacks' sensitivity to racism. In his 1933 writings, Du Bois embraced socialism, but asserted that "[c]olored labor has no common ground with white labor", a controversial position that was rooted in Du Bois's dislike of American labor unions, which had systematically excluded blacks for decades. Du Bois did not support the Communist Party in the U.S. and did not vote for their candidate in the 1932 presidential election, in spite of an African American on their ticket.

Black Reconstruction in America

Back in the world of academia, Du Bois was able to resume his study of Reconstruction, the topic of the 1910 paper that he presented to the American Historical Association. In 1935, he published his magnum opus, Black Reconstruction in America. The book presented the thesis, in the words of the historian David Levering Lewis, that "black people, suddenly admitted to citizenship in an environment of feral hostility, displayed admirable volition and intelligence as well as the indolence and ignorance inherent in three centuries of bondage."

Du Bois documented how black people were central figures in the American Civil War and Reconstruction era, and also showed how they made alliances with white politicians. He provided evidence that the coalition governments established public education in the South, and many needed social service programs. The book also demonstrated the ways in which black emancipation – the crux of Reconstruction – promoted a radical restructuring of United States society, as well as how and why the country failed to continue support for civil rights for blacks in the aftermath of Reconstruction.

The book's thesis ran counter to the orthodox interpretation of Reconstruction maintained by white historians, and the book was virtually ignored by mainstream historians until the 1960s. Thereafter, however, it ignited a "revisionist" trend in the historiography of Reconstruction, which emphasized black people's search for freedom and the era's radical policy changes. By the 21st century, Black Reconstruction was widely perceived as "the foundational text of revisionist African American historiography."

In the final chapter of the book, "XIV. The Propaganda of History", Du Bois evokes his efforts at writing an article for the Encyclopædia Britannica on the "history of the American Negro". After the editors had cut all reference to Reconstruction, he insisted that the following note appear in the entry: "White historians have ascribed the faults and failures of Reconstruction to Negro ignorance and corruption. But the Negro insists that it was Negro loyalty and the Negro vote alone that restored the South to the Union; established the new democracy, both for white and black, and instituted the public schools." The editors refused and, so, Du Bois withdrew his article.

Projected encyclopedia

In 1932, Du Bois was selected by several philanthropies, including the Phelps Stokes Fund, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, and the General Education Board, to be the managing editor for a proposed Encyclopedia of the Negro, a work which Du Bois had been contemplating for 30 years. After several years of planning and organizing, the philanthropies canceled the project in 1938 because some board members believed that Du Bois was too biased to produce an objective encyclopedia.

Trip around the world

Du Bois took a trip around the world in 1936, which included visits to Germany, China, and Japan. While in Germany, Du Bois remarked that he was treated with warmth and respect. After his return to the United States, he expressed his ambivalence about the Nazi regime. He admired how the Nazis had improved the German economy, but he was horrified by their treatment of the Jewish people, which he described as "an attack on civilization, comparable only to such horrors as the Spanish Inquisition and the African slave trade".

Following the 1905 Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War, Du Bois became impressed by the growing strength of Imperial Japan. He came to view the ascendant Japanese Empire as an antidote to Western imperialism, arguing for over three decades after the war that its rise represented a chance to break the monopoly that white nations had on international affairs. A representative of Japan's "Negro Propaganda Operations" traveled to the United States during the 1920s and 1930s, meeting with Du Bois and giving him a positive impression of Imperial Japan's racial policies.

In 1936, the Japanese ambassador arranged a trip to Japan for Du Bois and a small group of academics, visiting China, Japan, and Manchukuo (Manchuria). Du Bois viewed Japanese colonialism in Manchuria as benevolent; he wrote that "colonial enterprise by a colored nation need not imply the caste, exploitation and subjection which it has always implied in the case of white Europe." He also believed that it was natural for Chinese and Japanese to quarrel with each other as "relatives" and that the segregated schools in Manchuria were established because the natives spoke Chinese only. While disturbed by the eventual Japanese alliance with Nazi Germany, Du Bois also argued Japan was only compelled to enter the pact because of the hostility of the United States and United Kingdom, and he viewed American apprehensions over Japanese expansion in Asia as racially motivated both before and after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He was similarly disturbed by how Chinese culture might be extinguished under Japanese rule but argued that Western imperialism was a greater existential concern.

World War II

Du Bois opposed the US intervention in World War II, particularly in the Pacific War, because he believed that China and Japan were emerging from the clutches of white imperialists. He felt that the European Allies waging war against Japan was an opportunity for whites to reestablish their influence in Asia. He was deeply disappointed by the US government's plan for African Americans in the armed forces: Blacks were limited to 5.8% of the force, and there were to be no African-American combat units – virtually the same restrictions as in World War I. With blacks threatening to shift their support to President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Republican opponent Wendell Willkie in the 1940 election, Roosevelt appointed a few blacks to leadership posts in the military.

Dusk of Dawn, Du Bois's second autobiography, was published in 1940. The title refers to his hope that African Americans were passing out of the darkness of racism into an era of greater equality. The work is part autobiography, part history, and part sociological treatise. Du Bois described the book as "the autobiography of a concept of race ... elucidated and magnified and doubtless distorted in the thoughts and deeds which were mine ... Thus for all time my life is significant for all lives of men."

In 1943, at age 75, Du Bois was abruptly fired from his position at Atlanta University by college president Rufus Early Clement. Many scholars expressed outrage, prompting Atlanta University to provide Du Bois with a lifelong pension and the title of professor emeritus. Arthur Spingarn remarked that Du Bois spent his time in Atlanta "battering his life out against ignorance, bigotry, intolerance and slothfulness, projecting ideas nobody but he understands, and raising hopes for change which may be comprehended in a hundred years."

Turning down job offers from Fisk and Howard, Du Bois re-joined the NAACP as director of the Department of Special Research. Surprising many NAACP leaders, Du Bois jumped into the job with vigor and determination. During his 10−years hiatus, the NAACP's income had increased fourfold, and its membership had soared to 325,000 members.

Later life

United Nations

Du Bois was a member of the three-person delegation from the NAACP that attended the 1945 conference in San Francisco at which the United Nations was established. The NAACP delegation wanted the United Nations to endorse racial equality and to bring an end to the colonial era. To push the United Nations in that direction, Du Bois drafted a proposal that pronounced "[t]he colonial system of government ... is undemocratic, socially dangerous and a main cause of wars". The NAACP proposal received support from China, India, and the Soviet Union, but it was virtually ignored by the other major powers, and the NAACP proposals were not included in the final United Nations Charter.

After the United Nations conference, Du Bois published Color and Democracy: Colonies and Peace, a book that attacked colonial empires and, in the words of a most sympathetic reviewer, "contains enough dynamite to blow up the whole vicious system whereby we have comforted our white souls and lined the pockets of generations of free-booting capitalists."

In late 1945, Du Bois attended the fifth, and final, Pan-African Congress, in Manchester, England. The congress was the most productive of the five congresses, and there Du Bois met Kwame Nkrumah, the future first president of Ghana, who would later invite him to Africa.

Du Bois helped to submit petitions to the UN concerning discrimination against African Americans, the most noteworthy of which was the NAACP's "An Appeal to the World: A Statement on the Denial of Human Rights to Minorities in the Case of Citizens of Negro Descent in the United States of America and an Appeal to the United Nations for Redress". This advocacy laid the foundation for the later report and petition called "We Charge Genocide", submitted in 1951 by the Civil Rights Congress. "We Charge Genocide" accuses the U.S. of systematically sanctioning murders and inflicting harm against African Americans and therefore committing genocide.

Cold War

When the Cold War commenced in the mid-1940s, the NAACP distanced itself from communists, lest its funding or reputation suffer. The NAACP redoubled its efforts in 1947 after Life magazine published a piece by Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. claiming that the NAACP was heavily influenced by communists. Ignoring the NAACP's desires, Du Bois continued to fraternize with communist sympathizers such as Paul Robeson, Howard Fast and Shirley Graham (his future second wife). Du Bois wrote "I am not a communist ... On the other hand, I ... believe ... that Karl Marx ... put his finger squarely upon our difficulties ...".

In 1946, Du Bois wrote articles giving his assessment of the Soviet Union; he did not embrace communism and he criticized its dictatorship. However, he felt that capitalism was responsible for poverty and racism, and felt that socialism was an alternative that might ameliorate those problems. The Soviets explicitly rejected racial distinctions and class distinctions, leading Du Bois to conclude that the USSR was the "most hopeful country on earth".

Du Bois's association with prominent communists made him a liability for the NAACP, especially since the Federal Bureau of Investigation was starting to aggressively investigate communist sympathizers; so – by mutual agreement – he resigned from the NAACP for the second time in late 1948. After departing the NAACP, Du Bois started writing regularly for the leftist weekly newspaper the National Guardian, a relationship that would endure until 1961.

Du Bois was an early and lifelong supporter of Zionism. He viewed Palestinians as uncivilized and viewed Islam as the main factor in what he saw as a lack of progress. However, he did not express support for Israel during the Suez Crisis, instead backing Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Peace activism

Du Bois was a lifelong anti-war activist, but his efforts became more pronounced after World War II. In 1949, Du Bois spoke at the Scientific and Cultural Conference for World Peace in New York: "I tell you, people of America, the dark world is on the move! It wants and will have Freedom, Autonomy and Equality. It will not be diverted in these fundamental rights by dialectical splitting of political hairs ... Whites may, if they will, arm themselves for suicide. But the vast majority of the world's peoples will march on over them to freedom!"

In the spring of 1949, he spoke at the World Congress of the Partisans of Peace in Paris, saying to the large crowd: "Leading this new colonial imperialism comes my own native land built by my father's toil and blood, the United States. The United States is a great nation; rich by grace of God and prosperous by the hard work of its humblest citizens ... Drunk with power we are leading the world to hell in a new colonialism with the same old human slavery which once ruined us; and to a third World War which will ruin the world." Du Bois affiliated himself with a leftist organization, the National Council of Arts, Sciences and Professions, and he traveled to Moscow as its representative to speak at the All-Soviet Peace Conference in late 1949.

During this period, Du Bois also visited the remains of the Warsaw Ghetto, an experience he spoke about in a speech titled, "The Negro and the Warsaw Ghetto" delivered in 1949 and later published in 1952 in the magazine Jewish Life. In the address, Du Bois reflects on the destruction caused by the Nazi assault against Jewish peoples and considers the way in which the "race problem" could extend past a "color-line" and become "a matter of cultural patterns, perverted teaching and human hate and prejudice, which reached all sorts of people and caused endless evil to all men". Du Bois' speech champions a broader and more transnational approach to humanitarianism.

The FBI, McCarthyism, and trial

During the 1950s, the U.S. government's anti-communist McCarthyism campaign targeted Du Bois because of his socialist leanings. Socialist historian Manning Marable characterizes the government's treatment of Du Bois as "ruthless repression" and a "political assassination".

The FBI began to compile a file on Du Bois in 1942, investigating him for possible subversive activities. The original investigation appears to have ended in 1943 because the FBI was unable to discover sufficient evidence against Du Bois, but the FBI resumed its investigation in 1949, suspecting he was among a group of "Concealed Communists". The most aggressive government attack against Du Bois occurred in the early 1950s, as a consequence of his opposition to nuclear weapons. In 1950 he became chair of the newly created Peace Information Center (PIC), which worked to publicize the Stockholm Appeal in the United States. The primary purpose of the appeal was to gather signatures on a petition, asking governments around the world to ban all nuclear weapons.

In United States v. Peace Information Center, 97 F. Supp. 255 (D.D.C. 1951), the U.S. Justice Department alleged that the PIC was acting as an agent of a foreign state, and thus required the PIC to register with the federal government under the Foreign Agents Registration Act. Du Bois and other PIC leaders refused, and they were indicted for failure to register. After the indictment, some of Du Bois's associates distanced themselves from him, and the NAACP refused to issue a statement of support; but many labor figures and leftists – including Langston Hughes – supported Du Bois.

He was finally tried in 1951 and was represented by civil rights attorney Vito Marcantonio. The case was dismissed when the defense attorney told the judge that "Dr. Albert Einstein has offered to appear as character witness for Dr. Du Bois". Du Bois's memoir of the trial is In Battle for Peace. Even though Du Bois was not convicted, the government confiscated Du Bois's passport and withheld it for eight years.

Communism

Du Bois was bitterly disappointed that many of his colleagues – particularly the NAACP – did not support him during his 1951 PIC trial, whereas working class whites and blacks supported him enthusiastically. After the trial, Du Bois lived in Manhattan, writing and speaking, and continuing to associate primarily with leftist acquaintances. His primary concern was world peace, and he railed against military actions such as the Korean War, which he viewed as efforts by imperialist whites to maintain colored people in a submissive state.

In 1950, at the age of 82, Du Bois ran for U.S. Senator from New York on the American Labor Party ticket and received about 200,000 votes, or 4% of the statewide total. He continued to believe that capitalism was the primary culprit responsible for the subjugation of colored people around the world, and although he recognized the faults of the Soviet Union, he continued to uphold communism as a possible solution to racial problems. In the words of biographer David Lewis, Du Bois did not endorse communism for its own sake, but did so because "the enemies of his enemies were his friends". The same ambiguity characterized his opinions of Joseph Stalin: in 1940 he wrote disdainfully of the "Tyrant Stalin", but when Stalin died in 1953, Du Bois wrote a eulogy characterizing Stalin as "simple, calm, and courageous", and lauding him for being the "first [to] set Russia on the road to conquer race prejudice and make one nation out of its 140 groups without destroying their individuality".

The U.S. government prevented Du Bois from attending the 1955 Bandung Conference in Indonesia. The conference was the culmination of 40 years of Du Bois's dreams – a meeting of 29 nations from Africa and Asia, many recently independent, representing most of the world's colored peoples. The conference celebrated those nations' independence as they began to assert their power as non-aligned nations during the Cold War. Du Bois praised the conference as "pan-colored" and believed it would have decisive and long-lasting influence.

After the United States Supreme Court ruled in Kent v. Dulles[ that the State Department could not deny passports to citizens who refused to sign affidavits that they were not communists, Du Bois and his wife Shirley Graham Du Bois immediately applied for passports. The two visited both the Soviet Union and China during a 1958 to 1959 trip which Du Bois described as the most significant journey of his life. Du Bois later wrote approvingly of the conditions in both countries. In 1959, Du Bois gave a speech at Peking University in which he advocated for increased ties between the black people in the United States and China because "China is colored and knows to what a colored skin in this modern world subjects its owner." Du Bois stated that Africa and China should stand together. The speech was reprinted and widely circulated in China, including through the People's Daily and the Peking Review.

Du Bois and Graham Du Bois were staying at the border between Sichuan and Tibet when the 1959 Tibetan uprising began. Describing the events in his Autobiography, Du Bois concluded, "The landholders and slave drivers and religious fanatics revolted against the Chinese and failed as they deserved to. Tibet has belonged to China for centuries. The Communists linked the two by roads and began reforms in landholding, schools and trade, which now move quickly."

Du Bois became incensed in 1961 when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the 1950 McCarran Internal Security Act, a key piece of McCarthyist legislation which required communists to register with the government. To demonstrate his outrage, he joined the Communist Party in October 1961, at the age of 93. Around that time, he wrote: "I believe in communism. I mean by communism, a planned way of life in the production of wealth and work designed for building a state whose object is the highest welfare of its people and not merely the profit of a part." He asked Herbert Aptheker, a communist and historian of African American history, to be his literary executor.

Death in Africa

Nkrumah invited Du Bois to the Dominion of Ghana to participate in their independence celebration in 1957, but he was unable to attend because the U.S. government had confiscated his passport in 1951. By 1960 – the "Year of Africa" – Du Bois had recovered his passport, and was able to cross the Atlantic and celebrate the creation of the Republic of Ghana. Du Bois returned to Africa in late 1960 to attend the inauguration of Nnamdi Azikiwe as the first African governor of Nigeria.

While visiting Ghana in 1960, Du Bois spoke with its president about the creation of a new encyclopedia of the African diaspora, the Encyclopedia Africana. In early 1961, Ghana notified Du Bois that they had appropriated funds to support the encyclopedia project, and they invited him to travel to Ghana and manage the project there. In October 1961, at the age of 93, Du Bois and his wife traveled to Ghana to take up residence and commence work on the encyclopedia. In early 1963, the United States refused to renew his passport, so he made the symbolic gesture of becoming a citizen of Ghana.

While it is sometimes stated that Du Bois renounced his U.S. citizenship at that time, and he stated his intention to do so, Du Bois never actually did. His health declined during the two years he was in Ghana; he died on August 27, 1963, in the capital, Accra, at the age of 95. The following day, at the March on Washington, speaker Roy Wilkins asked the hundreds of thousands of marchers to honor Du Bois with a moment of silence. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, embodying many of the reforms Du Bois had campaigned for during his entire life, was enacted almost a year after his death.

Du Bois was given a state funeral on August 29–30, 1963, at Nkrumah's request, and was buried near the western wall of Christiansborg Castle (now Osu Castle), then the seat of government in Accra. In 1985, another state ceremony honored Du Bois. With the ashes of his wife Shirley Graham Du Bois, who had died in 1977, his body was re-interred at their former home in Accra, which was dedicated the W. E. B. Du Bois Memorial Centre for Pan African Culture in his memory. Du Bois's first wife Nina, their son Burghardt, and their daughter Yolande, who died in 1961, were buried in the cemetery of Great Barrington, Massachusetts, his hometown.

Personal life

Du Bois was organized and disciplined: his lifelong regimen was to rise at 7:15, work until 5:00, eat dinner and read a newspaper until 7:00, then read or socialize until he was in bed, invariably before 10:00. He was a meticulous planner, and frequently mapped out his schedules and goals on large pieces of graph paper. Many acquaintances found him to be distant and aloof, and he insisted on being addressed as "Dr. Du Bois". According to biographer David Levering, Du Bois would also "unfailingly insist upon the 'correct' pronunciation of his surname. 'The pronunciation of my name is Due Boyss, with the accent on the last syllable,' he would patiently explain to the uninformed." Although he was not gregarious, he formed several close friendships with associates such as Charles Young, Paul Laurence Dunbar, John Hope, Mary White Ovington, and Albert Einstein.

His closest friend was Joel Spingarn – a white man – but Du Bois never accepted Spingarn's offer to be on a first-name basis.[344] Du Bois was something of a dandy – he dressed formally, carried a walking stick, and walked with an air of confidence and dignity.[345] He was relatively short, standing at 5 feet 5.5 inches (166 cm), and always maintained a well-groomed mustache and goatee.[346] He enjoyed singing[347] and playing tennis.[52]

Du Bois married Nina Gomer (b. about 1870, m. 1896, d. 1950), with whom he had two children. Their son Burghardt died as an infant before their second child, daughter Yolande, was born. Yolande attended Fisk University and became a high school teacher in Baltimore.[348] Her father encouraged her marriage to Countee Cullen, a nationally known poet of the Harlem Renaissance.[349] They divorced within two years. She married again and had a daughter, Du Bois's only grandchild. That marriage also ended in divorce.

As a widower, Du Bois married Shirley Graham (m. 1951, d. 1977), an author, playwright, composer, and activist. She brought her son David Graham to the marriage. David grew close to Du Bois and took his stepfather's name; he also worked for African-American causes. The historian David Levering Lewis wrote that Du Bois engaged in several extramarital relationships.

Religion

Although Du Bois attended a New England Congregational church as a child, he abandoned organized religion while at Fisk College. As an adult, Du Bois described himself as agnostic or a freethinker, but at least one biographer concluded that Du Bois was virtually an atheist. However, another analyst of Du Bois's writings concluded that he had a religious voice, albeit radically different from other African-American religious voices of his era. Du Bois was credited with inaugurating a 20th-century spirituality to which Ralph Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston, and James Baldwin also belong.

When asked to lead public prayers, Du Bois would refuse. In his autobiography, Du Bois wrote:

When I became head of a department at Atlanta, the engagement was held up because again I balked at leading in prayer ... I flatly refused again to join any church or sign any church creed. ... I think the greatest gift of the Soviet Union to modern civilization was the dethronement of the clergy and the refusal to let religion be taught in the public schools.

Du Bois accused American churches of being the most discriminatory of all institutions. He also provocatively linked African American Christianity to indigenous African religions. He did occasionally acknowledge the beneficial role that religion played in African American life – as the "basic rock" which served as an anchor for African American communities – but in general disparaged African American churches and clergy because he felt they did not support the goals of racial equality and hindered activists' efforts.

Although Du Bois was not personally religious, he infused his writings with religious symbology. Many contemporaries viewed him as a prophet. His 1904 prose poem, "Credo", was written in the style of a religious creed and widely read by the African-American community. Moreover, Du Bois, both in his own fiction and in stories published in The Crisis, often drew analogies between the lynchings of African Americans and the crucifixion of Jesus. Between 1920 and 1940, Du Bois shifted from overt black messiah symbolism to more subtle messianic language.

Voting

In 1889, Du Bois became eligible to vote at the age of 21. During his life he followed the philosophy of voting for third parties if the Democratic and Republican parties were unsatisfactory; or voting for the lesser of two evils if a third option was not available.