In chemical analysis, chromatography is a laboratory technique for the separation of a mixture into its components. The mixture is dissolved in a fluid solvent (gas or liquid) called the mobile phase, which carries it through a system (a column, a capillary tube, a plate, or a sheet) on which a material called the stationary phase is fixed. Because the different constituents of the mixture tend to have different affinities for the stationary phase and are retained for different lengths of time depending on their interactions with its surface sites, the constituents travel at different apparent velocities in the mobile fluid, causing them to separate. The separation is based on the differential partitioning between the mobile and the stationary phases. Subtle differences in a compound's partition coefficient result in differential retention on the stationary phase and thus affect the separation.

Chromatography may be preparative or analytical. The purpose of preparative chromatography is to separate the components of a mixture for later use, and is thus a form of purification. This process is associated with higher costs due to its mode of production. Analytical chromatography is done normally with smaller amounts of material and is for establishing the presence or measuring the relative proportions of analytes in a mixture. The two types are not mutually exclusive.

Etymology and pronunciation

Chromatography, pronounced /ˌkroʊməˈtɒɡrəfi/, is derived from Greek χρῶμα chroma, which means "color", and γράφειν graphein, which means "to write". The combination of these two terms was directly inherited from the invention of the technique first used to separate biological pigments.

History

Chromatography was first devised at the University of Kazan by the Italian-born Russian scientist Mikhail Tsvet in 1900. He developed the technique and coined the term chromatography in the first decade of the 20th century, primarily for the separation of plant pigments such as chlorophyll, carotenes, and xanthophylls. Since these components separate in bands of different colors (green, orange, and yellow, respectively) they directly inspired the name of the technique. New types of chromatography developed during the 1930s and 1940s made the technique useful for many separation processes.

Chromatography technique developed substantially as a result of the work of Archer John Porter Martin and Richard Laurence Millington Synge during the 1940s and 1950s, for which they won the 1952 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. They established the principles and basic techniques of partition chromatography, and their work encouraged the rapid development of several chromatographic methods: paper chromatography, gas chromatography, and what would become known as high-performance liquid chromatography. Since then, the technology has advanced rapidly. Researchers found that the main principles of Tsvet's chromatography could be applied in many different ways, resulting in the different varieties of chromatography described below. Advances are continually improving the technical performance of chromatography, allowing the separation of increasingly similar molecules.

Terms

- Analyte – the substance to be separated during chromatography. It is also normally what is needed from the mixture.

- Analytical chromatography – the use of chromatography to determine the existence and possibly also the concentration of analyte(s) in a sample.

- Bonded phase – a stationary phase that is covalently bonded to the support particles or to the inside wall of the column tubing.

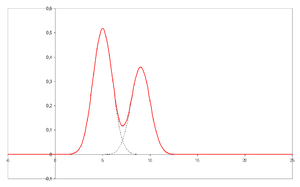

- Chromatogram – the visual output of the chromatograph. In the

case of an optimal separation, different peaks or patterns on the

chromatogram correspond to different components of the separated

mixture.

Plotted on the x-axis is the retention time and plotted on the y-axis a signal (for example obtained by a spectrophotometer, mass spectrometer

or a variety of other detectors) corresponding to the response created

by the analytes exiting the system. In the case of an optimal system the

signal is proportional to the concentration of the specific analyte

separated.

Plotted on the x-axis is the retention time and plotted on the y-axis a signal (for example obtained by a spectrophotometer, mass spectrometer

or a variety of other detectors) corresponding to the response created

by the analytes exiting the system. In the case of an optimal system the

signal is proportional to the concentration of the specific analyte

separated. - Chromatograph – an instrument that enables a sophisticated separation, e.g. gas chromatographic or liquid chromatographic separation.

- Chromatography – a physical method of separation that distributes components to separate between two phases, one stationary (stationary phase), the other (the mobile phase) moving in a definite direction.

- Eluent (sometimes spelled eluant) – the solvent or solvent fixure used in elution chromatography and is synonymous with mobile phase.

- Eluate – the mixture of solute (see Eluite) and solvent (see Eluent) exiting the column.

- Effluent – the stream flowing out of a chromatographic column. In practise, it is used synonymously with eluate, but the term more precisely refers to the stream independent of separation taking place.

- Eluite – a more precise term for solute or analyte. It is a sample component leaving the chromatographic column.

- Eluotropic series – a list of solvents ranked according to their eluting power.

- Immobilized phase – a stationary phase that is immobilized on the support particles, or on the inner wall of the column tubing.

- Mobile phase – the phase that moves in a definite direction. It may be a liquid (LC and capillary electrochromatography, CEC), a gas (GC), or a supercritical fluid (supercritical-fluid chromatography, SFC). The mobile phase consists of the sample being separated/analyzed and the solvent that moves the sample through the column. In the case of HPLC the mobile phase consists of a non-polar solvent(s) such as hexane in normal phase or a polar solvent such as methanol in reverse phase chromatography and the sample being separated. The mobile phase moves through the chromatography column (the stationary phase) where the sample interacts with the stationary phase and is separated.

- Preparative chromatography – the use of chromatography to purify sufficient quantities of a substance for further use, rather than analysis.

- Retention time – the characteristic time it takes for a particular analyte to pass through the system (from the column inlet to the detector) under set conditions. See also: Kovats' retention index

- Sample – the matter analyzed in chromatography. It may consist of a single component or it may be a mixture of components. When the sample is treated in the course of an analysis, the phase or the phases containing the analytes of interest is/are referred to as the sample whereas everything out of interest separated from the sample before or in the course of the analysis is referred to as waste.

- Solute – the sample components in partition chromatography.

- Solvent – any substance capable of solubilizing another substance, and especially the liquid mobile phase in liquid chromatography.

- Stationary phase – the substance fixed in place for the chromatography procedure. Examples include the silica layer in thin-layer chromatography

- Detector – the instrument used for qualitative and quantitative detection of analytes after separation.

Chromatography is based on the concept of partition coefficient. Any solute partitions between two immiscible solvents. When one make one solvent immobile (by adsorption on a solid support matrix) and another mobile it results in most common applications of chromatography. If the matrix support, or stationary phase, is polar (e.g, cellulose, silica etc.) it is forward phase chromatography. Otherwise this technique is known as reversed phase, where a non-polar stationary phase (e.g, non-polar derivative of C-18) is used.

Techniques by chromatographic bed shape

Column chromatography

Column chromatography is a separation technique in which the stationary bed is within a tube. The particles of the solid stationary phase or the support coated with a liquid stationary phase may fill the whole inside volume of the tube (packed column) or be concentrated on or along the inside tube wall leaving an open, unrestricted path for the mobile phase in the middle part of the tube (open tubular column). Differences in rates of movement through the medium are calculated to different retention times of the sample. In 1978, W. Clark Still introduced a modified version of column chromatography called flash column chromatography (flash). The technique is very similar to the traditional column chromatography, except that the solvent is driven through the column by applying positive pressure. This allowed most separations to be performed in less than 20 minutes, with improved separations compared to the old method. Modern flash chromatography systems are sold as pre-packed plastic cartridges, and the solvent is pumped through the cartridge. Systems may also be linked with detectors and fraction collectors providing automation. The introduction of gradient pumps resulted in quicker separations and less solvent usage.

In expanded bed adsorption, a fluidized bed is used, rather than a solid phase made by a packed bed. This allows omission of initial clearing steps such as centrifugation and filtration, for culture broths or slurries of broken cells.

Phosphocellulose chromatography utilizes the binding affinity of many DNA-binding proteins for phosphocellulose. The stronger a protein's interaction with DNA, the higher the salt concentration needed to elute that protein.

Planar chromatography

Planar chromatography is a separation technique in which the stationary phase is present as or on a plane. The plane can be a paper, serving as such or impregnated by a substance as the stationary bed (paper chromatography) or a layer of solid particles spread on a support such as a glass plate (thin-layer chromatography). Different compounds in the sample mixture travel different distances according to how strongly they interact with the stationary phase as compared to the mobile phase. The specific Retention factor (Rf) of each chemical can be used to aid in the identification of an unknown substance.

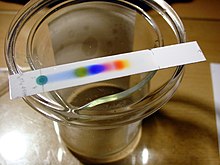

Paper chromatography

Paper chromatography is a technique that involves placing a small dot or line of sample solution onto a strip of chromatography paper. The paper is placed in a container with a shallow layer of solvent and sealed. As the solvent rises through the paper, it meets the sample mixture, which starts to travel up the paper with the solvent. This paper is made of cellulose, a polar substance, and the compounds within the mixture travel further if they are less polar. More polar substances bond with the cellulose paper more quickly, and therefore do not travel as far.

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC)

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) is a widely employed laboratory technique used to separate different biochemicals on the basis of their relative attractions to the stationary and mobile phases. It is similar to paper chromatography. However, instead of using a stationary phase of paper, it involves a stationary phase of a thin layer of adsorbent like silica gel, alumina, or cellulose on a flat, inert substrate. TLC is very versatile; multiple samples can be separated simultaneously on the same layer, making it very useful for screening applications such as testing drug levels and water purity.

Possibility of cross-contamination is low since each separation is performed on a new layer. Compared to paper, it has the advantage of faster runs, better separations, better quantitative analysis, and the choice between different adsorbents. For even better resolution and faster separation that utilizes less solvent, high-performance TLC can be used. An older popular use had been to differentiate chromosomes by observing distance in gel (separation of was a separate step).

Displacement chromatography

The basic principle of displacement chromatography is: A molecule with a high affinity for the chromatography matrix (the displacer) competes effectively for binding sites, and thus displaces all molecules with lesser affinities. There are distinct differences between displacement and elution chromatography. In elution mode, substances typically emerge from a column in narrow, Gaussian peaks. Wide separation of peaks, preferably to baseline, is desired for maximum purification. The speed at which any component of a mixture travels down the column in elution mode depends on many factors. But for two substances to travel at different speeds, and thereby be resolved, there must be substantial differences in some interaction between the biomolecules and the chromatography matrix. Operating parameters are adjusted to maximize the effect of this difference. In many cases, baseline separation of the peaks can be achieved only with gradient elution and low column loadings. Thus, two drawbacks to elution mode chromatography, especially at the preparative scale, are operational complexity, due to gradient solvent pumping, and low throughput, due to low column loadings. Displacement chromatography has advantages over elution chromatography in that components are resolved into consecutive zones of pure substances rather than "peaks". Because the process takes advantage of the nonlinearity of the isotherms, a larger column feed can be separated on a given column with the purified components recovered at significantly higher concentrations.

Techniques by physical state of mobile phase

Gas chromatography

Gas chromatography (GC), also sometimes known as gas-liquid chromatography, (GLC), is a separation technique in which the mobile phase is a gas. Gas chromatographic separation is always carried out in a column, which is typically "packed" or "capillary". Packed columns are the routine work horses of gas chromatography, being cheaper and easier to use and often giving adequate performance. Capillary columns generally give far superior resolution and although more expensive are becoming widely used, especially for complex mixtures. Further, capillary columns can be split into three classes: porous layer open tubular (PLOT), wall-coated open tubular (WCOT) and support-coated open tubular (SCOT) columns. PLOT columns are unique in a way that the stationary phase is adsorbed to the column walls, while WCOT columns have a stationary phase that is chemically bonded to the walls. SCOT columns are in a way the combination of the two types mentioned in a way that they have support particles adhered to column walls, but those particles have liquid phase chemically bonded onto them. Both types of column are made from non-adsorbent and chemically inert materials. Stainless steel and glass are the usual materials for packed columns and quartz or fused silica for capillary columns.

Gas chromatography is based on a partition equilibrium of analyte between a solid or viscous liquid stationary phase (often a liquid silicone-based material) and a mobile gas (most often helium). The stationary phase is adhered to the inside of a small-diameter (commonly 0.53 – 0.18mm inside diameter) glass or fused-silica tube (a capillary column) or a solid matrix inside a larger metal tube (a packed column). It is widely used in analytical chemistry; though the high temperatures used in GC make it unsuitable for high molecular weight biopolymers or proteins (heat denatures them), frequently encountered in biochemistry, it is well suited for use in the petrochemical, environmental monitoring and remediation, and industrial chemical fields. It is also used extensively in chemistry research.

Liquid chromatography

Liquid chromatography (LC) is a separation technique in which the mobile phase is a liquid. It can be carried out either in a column or a plane. Present day liquid chromatography that generally utilizes very small packing particles and a relatively high pressure is referred to as high-performance liquid chromatography.

In HPLC the sample is forced by a liquid at high pressure (the mobile phase) through a column that is packed with a stationary phase composed of irregularly or spherically shaped particles, a porous monolithic layer, or a porous membrane. Monoliths are "sponge-like chromatographic media" and are made up of an unending block of organic or inorganic parts. HPLC is historically divided into two different sub-classes based on the polarity of the mobile and stationary phases. Methods in which the stationary phase is more polar than the mobile phase (e.g., toluene as the mobile phase, silica as the stationary phase) are termed normal phase liquid chromatography (NPLC) and the opposite (e.g., water-methanol mixture as the mobile phase and C18 (octadecylsilyl) as the stationary phase) is termed reversed phase liquid chromatography (RPLC).

Supercritical fluid chromatography

Supercritical fluid chromatography is a separation technique in which the mobile phase is a fluid above and relatively close to its critical temperature and pressure.

Specific techniques under this broad heading are listed below.

Affinity chromatography

Affinity chromatography is based on selective non-covalent interaction between an analyte and specific molecules. It is very specific, but not very robust. It is often used in biochemistry in the purification of proteins bound to tags. These fusion proteins are labeled with compounds such as His-tags, biotin or antigens, which bind to the stationary phase specifically. After purification, these tags are usually removed and the pure protein is obtained.

Affinity chromatography often utilizes a biomolecule's affinity for the cations of a metal (Zn, Cu, Fe, etc.). Columns are often manually prepared and could be designed specifically for the proteins of interest. Traditional affinity columns are used as a preparative step to flush out unwanted biomolecules, or as a primary step in analyzing a protein with unknown physical properties.

However, liquid chromatography techniques exist that do utilize affinity chromatography properties. Immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) is useful to separate the aforementioned molecules based on the relative affinity for the metal. Often these columns can be loaded with different metals to create a column with a targeted affinity.

Techniques by separation mechanism

Ion exchange chromatography

Ion exchange chromatography (usually referred to as ion chromatography) uses an ion exchange mechanism to separate analytes based on their respective charges. It is usually performed in columns but can also be useful in planar mode. Ion exchange chromatography uses a charged stationary phase to separate charged compounds including anions, cations, amino acids, peptides, and proteins. In conventional methods the stationary phase is an ion-exchange resin that carries charged functional groups that interact with oppositely charged groups of the compound to retain. There are two types of ion exchange chromatography: Cation-Exchange and Anion-Exchange. In the Cation-Exchange Chromatography the stationary phase has negative charge and the exchangeable ion is a cation, whereas, in the Anion-Exchange Chromatography the stationary phase has positive charge and the exchangeable ion is an anion. Ion exchange chromatography is commonly used to purify proteins using FPLC.

Size-exclusion chromatography

Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) is also known as gel permeation chromatography (GPC) or gel filtration chromatography and separates molecules according to their size (or more accurately according to their hydrodynamic diameter or hydrodynamic volume). Smaller molecules are able to enter the pores of the media and, therefore, molecules are trapped and removed from the flow of the mobile phase. The average residence time in the pores depends upon the effective size of the analyte molecules. However, molecules that are larger than the average pore size of the packing are excluded and thus suffer essentially no retention; such species are the first to be eluted. It is generally a low-resolution chromatography technique and thus it is often reserved for the final, "polishing" step of a purification. It is also useful for determining the tertiary structure and quaternary structure of purified proteins, especially since it can be carried out under native solution conditions.

Expanded bed adsorption chromatographic separation

An expanded bed chromatographic adsorption (EBA) column for a biochemical separation process comprises a pressure equalization liquid distributor having a self-cleaning function below a porous blocking sieve plate at the bottom of the expanded bed, an upper part nozzle assembly having a backflush cleaning function at the top of the expanded bed, a better distribution of the feedstock liquor added into the expanded bed ensuring that the fluid passed through the expanded bed layer displays a state of piston flow. The expanded bed layer displays a state of piston flow. The expanded bed chromatographic separation column has advantages of increasing the separation efficiency of the expanded bed.

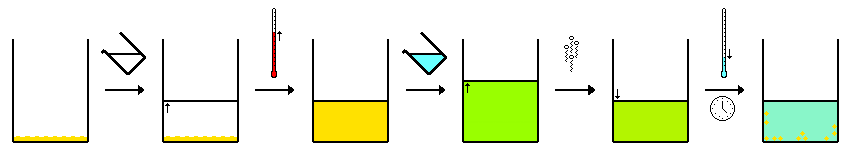

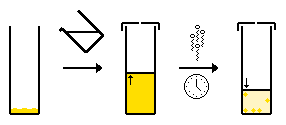

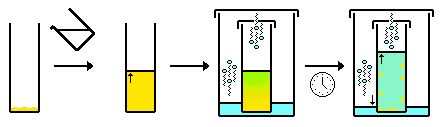

Expanded-bed adsorption (EBA) chromatography is a convenient and effective technique for the capture of proteins directly from unclarified crude sample. In EBA chromatography, the settled bed is first expanded by upward flow of equilibration buffer. The crude feed, which is a mixture of soluble proteins, contaminants, cells, and cell debris, is then passed upward through the expanded bed. Target proteins are captured on the adsorbent, while particulates and contaminants pass through. A change to elution buffer while maintaining upward flow results in desorption of the target protein in expanded-bed mode. Alternatively, if the flow is reversed, the adsorbed particles will quickly settle and the proteins can be desorbed by an elution buffer. The mode used for elution (expanded-bed versus settled-bed) depends on the characteristics of the feed. After elution, the adsorbent is cleaned with a predefined cleaning-in-place (CIP) solution, with cleaning followed by either column regeneration (for further use) or storage.

Special techniques

Reversed-phase chromatography

Reversed-phase chromatography (RPC) is any liquid chromatography procedure in which the mobile phase is significantly more polar than the stationary phase. It is so named because in normal-phase liquid chromatography, the mobile phase is significantly less polar than the stationary phase. Hydrophobic molecules in the mobile phase tend to adsorb to the relatively hydrophobic stationary phase. Hydrophilic molecules in the mobile phase will tend to elute first. Separating columns typically comprise a C8 or C18 carbon-chain bonded to a silica particle substrate.

Hydrophobic interaction chromatography

Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC) is a purification and analytical technique that separates analytes, such as proteins, based on hydrophobic interactions between that analyte and the chromatographic matrix. It can provide a non-denaturing orthogonal approach to reversed phase separation, preserving native structures and potentially protein activity. In hydrophobic interaction chromatography, the matrix material is lightly substituted with hydrophobic groups. These groups can range from methyl, ethyl, propyl, butyl, octyl, or phenyl groups. At high salt concentrations, non-polar sidechains on the surface on proteins "interact" with the hydrophobic groups; that is, both types of groups are excluded by the polar solvent (hydrophobic effects are augmented by increased ionic strength). Thus, the sample is applied to the column in a buffer which is highly polar, which drives an association of hydrophobic patches on the analyte with the stationary phase. The eluent is typically an aqueous buffer with decreasing salt concentrations, increasing concentrations of detergent (which disrupts hydrophobic interactions), or changes in pH. Of critical importance is the type of salt used, with more kosmotropic salts as defined by the Hofmeister series providing the most water structuring around the molecule and resulting hydrophobic pressure. Ammonium sulfate is frequently used for this purpose. The addition of organic solvents or other less polar constituents may assist in improving resolution.

In general, Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC) is advantageous if the sample is sensitive to pH change or harsh solvents typically used in other types of chromatography but not high salt concentrations. Commonly, it is the amount of salt in the buffer which is varied. In 2012, Müller and Franzreb described the effects of temperature on HIC using Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) with four different types of hydrophobic resin. The study altered temperature as to effect the binding affinity of BSA onto the matrix. It was concluded that cycling temperature from 40 to 10 degrees Celsius would not be adequate to effectively wash all BSA from the matrix but could be very effective if the column would only be used a few times. Using temperature to effect change allows labs to cut costs on buying salt and saves money.

If high salt concentrations along with temperature fluctuations want to be avoided one can use a more hydrophobic to compete with one's sample to elute it. This so-called salt independent method of HIC showed a direct isolation of Human Immunoglobulin G (IgG) from serum with satisfactory yield and used β-cyclodextrin as a competitor to displace IgG from the matrix. This largely opens up the possibility of using HIC with samples which are salt sensitive as we know high salt concentrations precipitate proteins.

Hydrodynamic chromatography

Hydrodynamic chromatography (HDC) is derived from the observed phenomenon that large droplets move faster than small ones. In a column, this happens because the center of mass of larger droplets is prevented from being as close to the sides of the column as smaller droplets because of their larger overall size. Larger droplets will elute first from the middle of the column while smaller droplets stick to the sides of the column and elute last. This form of chromatography is useful for separating analytes by molar mass (or molecular mass), size, shape, and structure when used in conjunction with light scattering detectors, viscometers, and refractometers. The two main types of HDC are open tube and packed column. Open tube offers rapid separation times for small particles, whereas packed column HDC can increase resolution and is better suited for particles with an average molecular mass larger than daltons. HDC differs from other types of chromatography because the separation only takes place in the interstitial volume, which is the volume surrounding and in between particles in a packed column.

HDC shares the same order of elution as Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) but the two processes still vary in many ways. In a study comparing the two types of separation, Isenberg, Brewer, Côté, and Striegel use both methods for polysaccharide characterization and conclude that HDC coupled with multiangle light scattering (MALS) achieves more accurate molar mass distribution when compared to off-line MALS than SEC in significantly less time. This is largely due to SEC being a more destructive technique because of the pores in the column degrading the analyte during separation, which tends to impact the mass distribution. However, the main disadvantage of HDC is low resolution of analyte peaks, which makes SEC a more viable option when used with chemicals that are not easily degradable and where rapid elution is not important.

HDC plays an especially important role in the field of microfluidics. The first successful apparatus for HDC-on-a-chip system was proposed by Chmela, et al. in 2002. Their design was able to achieve separations using an 80 mm long channel on the timescale of 3 minutes for particles with diameters ranging from 26 to 110 nm, but the authors expressed a need to improve the retention and dispersion parameters. In a 2010 publication by Jellema, Markesteijn, Westerweel, and Verpoorte, implementing HDC with a recirculating bidirectional flow resulted in high resolution, size based separation with only a 3 mm long channel. Having such a short channel and high resolution was viewed as especially impressive considering that previous studies used channels that were 80 mm in length. For a biological application, in 2007, Huh, et al. proposed a microfluidic sorting device based on HDC and gravity, which was useful for preventing potentially dangerous particles with diameter larger than 6 microns from entering the bloodstream when injecting contrast agents in ultrasounds. This study also made advances for environmental sustainability in microfluidics due to the lack of outside electronics driving the flow, which came as an advantage of using a gravity based device.

Two-dimensional chromatography

In some cases, the selectivity provided by the use of one column can be insufficient to provide resolution of analytes in complex samples. Two-dimensional chromatography aims to increase the resolution of these peaks by using a second column with different physico-chemical (chemical classification) properties. Since the mechanism of retention on this new solid support is different from the first dimensional separation, it can be possible to separate compounds by two-dimensional chromatography that are indistinguishable by one-dimensional chromatography. Furthermore, the separation on the second dimension occurs faster than the first dimension. An example of a TDC separation is where the sample is spotted at one corner of a square plate, developed, air-dried, then rotated by 90° and usually redeveloped in a second solvent system.

Two-dimensional chromatography can be applied to GC or LC separations. The heart-cutting approach selects a specific region of interest on the first dimension for separation, and the comprehensive approach uses all analytes in the second-dimension separation.

Simulated moving-bed chromatography

The simulated moving bed (SMB) technique is a variant of high performance liquid chromatography; it is used to separate particles and/or chemical compounds that would be difficult or impossible to resolve otherwise. This increased separation is brought about by a valve-and-column arrangement that is used to lengthen the stationary phase indefinitely. In the moving bed technique of preparative chromatography the feed entry and the analyte recovery are simultaneous and continuous, but because of practical difficulties with a continuously moving bed, simulated moving bed technique was proposed. In the simulated moving bed technique instead of moving the bed, the sample inlet and the analyte exit positions are moved continuously, giving the impression of a moving bed. True moving bed chromatography (TMBC) is only a theoretical concept. Its simulation, SMBC is achieved by the use of a multiplicity of columns in series and a complex valve arrangement. This valve arrangement provides for sample and solvent feed and analyte and waste takeoff at appropriate locations of any column, whereby it allows switching at regular intervals the sample entry in one direction, the solvent entry in the opposite direction, whilst changing the analyte and waste takeoff positions appropriately as well.

Pyrolysis gas chromatography

Pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry is a method of chemical analysis in which the sample is heated to decomposition to produce smaller molecules that are separated by gas chromatography and detected using mass spectrometry.

Pyrolysis is the thermal decomposition of materials in an inert atmosphere or a vacuum. The sample is put into direct contact with a platinum wire, or placed in a quartz sample tube, and rapidly heated to 600–1000 °C. Depending on the application even higher temperatures are used. Three different heating techniques are used in actual pyrolyzers: Isothermal furnace, inductive heating (Curie point filament), and resistive heating using platinum filaments. Large molecules cleave at their weakest points and produce smaller, more volatile fragments. These fragments can be separated by gas chromatography. Pyrolysis GC chromatograms are typically complex because a wide range of different decomposition products is formed. The data can either be used as fingerprints to prove material identity or the GC/MS data is used to identify individual fragments to obtain structural information. To increase the volatility of polar fragments, various methylating reagents can be added to a sample before pyrolysis.

Besides the usage of dedicated pyrolyzers, pyrolysis GC of solid and liquid samples can be performed directly inside Programmable Temperature Vaporizer (PTV) injectors that provide quick heating (up to 30 °C/s) and high maximum temperatures of 600–650 °C. This is sufficient for some pyrolysis applications. The main advantage is that no dedicated instrument has to be purchased and pyrolysis can be performed as part of routine GC analysis. In this case, quartz GC inlet liners have to be used. Quantitative data can be acquired, and good results of derivatization inside the PTV injector are published as well.

Fast protein liquid chromatography

Fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC), is a form of liquid chromatography that is often used to analyze or purify mixtures of proteins. As in other forms of chromatography, separation is possible because the different components of a mixture have different affinities for two materials, a moving fluid (the "mobile phase") and a porous solid (the stationary phase). In FPLC the mobile phase is an aqueous solution, or "buffer". The buffer flow rate is controlled by a positive-displacement pump and is normally kept constant, while the composition of the buffer can be varied by drawing fluids in different proportions from two or more external reservoirs. The stationary phase is a resin composed of beads, usually of cross-linked agarose, packed into a cylindrical glass or plastic column. FPLC resins are available in a wide range of bead sizes and surface ligands depending on the application.

Countercurrent chromatography

Countercurrent chromatography (CCC) is a type of liquid-liquid chromatography, where both the stationary and mobile phases are liquids and the liquid stationary phase is held stagnant by a strong centrifugal force.

Hydrodynamic countercurrent chromatography (CCC)

The operating principle of CCC instrument requires a column consisting of an open tube coiled around a bobbin. The bobbin is rotated in a double-axis gyratory motion (a cardioid), which causes a variable gravity (G) field to act on the column during each rotation. This motion causes the column to see one partitioning step per revolution and components of the sample separate in the column due to their partitioning coefficient between the two immiscible liquid phases used. There are many types of CCC available today. These include HSCCC (High Speed CCC) and HPCCC (High Performance CCC). HPCCC is the latest and best-performing version of the instrumentation available currently.

Centrifugal partition chromatography (CPC)

In the CPC (centrifugal partition chromatography or hydrostatic countercurrent chromatography) instrument, the column consists of a series of cells interconnected by ducts attached to a rotor. This rotor rotates on its central axis creating the centrifugal field necessary to hold the stationary phase in place. The separation process in CPC is governed solely by the partitioning of solutes between the stationary and mobile phases, which mechanism can be easily described using the partition coefficients (KD) of solutes. CPC instruments are commercially available for laboratory, pilot, and industrial-scale separations with different sizes of columns ranging from some 10 milliliters to 10 liters in volume.

Periodic counter-current chromatography

In contrast to Counter current chromatography (see above), periodic counter-current chromatography (PCC) uses a solid stationary phase and only a liquid mobile phase. It thus is much more similar to conventional affinity chromatography than to counter current chromatography. PCC uses multiple columns, which during the loading phase are connected in line. This mode allows for overloading the first column in this series without losing product, which already breaks through the column before the resin is fully saturated. The breakthrough product is captured on the subsequent column(s). In a next step the columns are disconnected from one another. The first column is washed and eluted, while the other column(s) are still being loaded. Once the (initially) first column is re-equilibrated, it is re-introduced to the loading stream, but as last column. The process then continues in a cyclic fashion.

Chiral chromatography

Chiral chromatography involves the separation of stereoisomers. In the case of enantiomers, these have no chemical or physical differences apart from being three-dimensional mirror images. To enable chiral separations to take place, either the mobile phase or the stationary phase must themselves be made chiral, giving differing affinities between the analytes. Chiral chromatography HPLC columns (with a chiral stationary phase) in both normal and reversed phase are commercially available.

Conventional chromatography are incapable of separating racemic mixtures of enantiomers. However, in some cases nonracemic mixtures of enantiomers may be separated unexpectedly by conventional liquid chromatography (e.g. HPLC without chiral mobile phase or stationary phase ).

Aqueous normal-phase chromatography

Aqueous normal-phase (ANP) chromatography is characterized by the elution behavior of classical normal phase mode (i.e. where the mobile phase is significantly less polar than the stationary phase) in which water is one of the mobile phase solvent system components. It is distinguished from hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) in that the retention mechanism is due to adsorption rather than partitioning.