In order to understand the radical animal rights and environmental movements, it helps to know a bit about punk rock.

—Will Potter, 2011

Animal rights are closely associated with two ideologies of the punk subculture: anarcho-punk and straight edge. This association dates back to the 1980s and has been expressed in areas that include song lyrics, benefit concerts for animal rights organisations, and militant actions of activists influenced by punk music. Among the latter, Rod Coronado, Peter Daniel Young and members of SHAC are notable. This issue spread into various punk rock and hardcore subgenres, e.g. crust punk, metalcore and grindcore, eventually becoming a distinctive feature of punk culture.

The inculcation of some concepts and practices related to animal rights in the collective consciousness has been substantially pioneered and influenced by the punk movement. This association continues on into the 21st century, as evinced by the prominence of international vegan punk events such as Ieperfest in Belgium, Fluff Fest in Czech Republic, and Verdurada in Brazil.

Overview and analysis

The relationship between punk and animal rights is highlighted in the imagery and lyrics of these bands, the content of zines, benefit concerts and albums for animal activist causes, and the convergence between punk and veganism in cafés, social centres, Food Not Bombs chapters, organisations such as the Animal Defense League and ABC No Rio (United States), and hunt saboteur groups (United Kingdom). Veganism has become the social norm in some communities of the anarcho-punk (current within punk rock that promotes anarchism) and straight edge (hardcore punk subculture based on abstinence from alcohol, tobacco and other recreational drugs) subcultures. For their part, the devotees of the Hare Krishna tradition, present in the krishnacore subgenre, are required to be vegetarians.

A 2014 study indicates that vegan punks are more likely to remain politically active through their diets and lifestyles than those who do not belong to this subculture. The majority of those incarcerated for illicit animal activism in the late 1990s and early 2000s were involved in hardcore punk music. In the anglosphere, although women are probably the greatest part of animal rights and environmental advocacy, young white men constitute the majority of both eco-animal rights criminality and the "hypermasculine" vegan straight edge milieu, coinciding with the propaganda success of organisations such as the Earth Liberation Front. Despite these correlations, the sociologists Will Boisseau and Jim Donaghey state that not all punks are vegans or are even interested in animal rights, while sociologist Ross Haenfler writes that tolerant straight edgers have always outnumbered their militant counterparts, who, nevertheless, "overshadowed much of the scene" for their violent actions.

Politics and religion

Vegetarianism, widely stigmatized as an Oriental and feminine practice, helps to differentiate punks from the mainstream, neatly corresponds to punk egalitarian values, and offers a direct challenge to the gender relations perceived in meat.

—Dylan Clark, 2004

Researcher Kirsty Lohman points out that punk's concern for animal welfare is placed in broader politics of environmental awareness and anti-consumerism, suggesting a form of continuity with previous countercultures such as the hippies and avant-gardes. One of the main characteristics of punk is its anti-authoritarian nature that includes a belief in liberation, concept which quickly extended into compassion for animals. In line with this, author Craig O'Hara said that "politically minded punks have viewed our treatment of animals as another of the many existing forms of oppression." Furthermore, due to the substantial affiliation between meat eating and masculinity, many punks consider their vegetarian lifestyles as, at least partly, a feminist practice. For these reasons, Boisseau and Donaghey suggest that the relationship between punk culture and animal rights and veganism is best understood within the framework of anarchism and intersectionality.

Unlike anarcho-punk, straight edge is not inherently political. For many straight edgers, as stated by Haenfler, "the personal is the political", choosing to live out their lifestyle (e.g. by adopting vegetarian diets) rather than engaging in traditional political protest. There have also been left-wing, conservative, radical, anarchist and religious interpretations of straight edge. Some straight edge people became Hare Krishnas because the latter provides a transcendental and philosophical framework wherein lay the commitments of non-drug use, vegetarianism and avoidance of illicit sex. Francis Stewart of the University of Stirling explained that there is still an anarchist influence on hardcore punk and straight edge, even if it were subtle, especially in regards to veganism and animal liberation and in the position of these within larger patterns of oppression. In 2017, she observed that straight edge has had an increasing hybridisation with anarchism.

Some radical political circles and authors have criticised some straight edge branches, in particular its 1990s American form, for their "self-righteous militancy", "reductionist focus on animal rights and environmental issues," and a religious leaning "that, in its worst forms, resembled reactionary Christian doctrines", according to anarchist writer Gabriel Kuhn. By the same token, other authors, such as music theorist Jonathan Pieslak, as well as straight edge activists argue that left-wing socio-political and politically correct agendas are detrimental to the movement because the scope of supporters is actually narrowed in broadening its causes since not everyone agrees on all of them. Instead, they propose the initial biocentrism which allowed highly divergent perspectives so long as the animals and earth were first.

Despite their differences, sociologist Erik Hannerz highlights that anarcho-punk and straight edge not only coincide with animal rights, but both also emphasise a do-it-yourself (DIY) ethic and downplay a conspicuous style in favour of calling to action, linking their lifestyles to political action. Elsewhere, Boisseau and Donaghey write that many people exposed to animal rights and veganism continue their activism after ending their involvement in punk scenes, indicating the politicising role of these subcultures.

Influence on participants

Politicisation through punk typically involves an awareness of animal liberation through song lyrics and albums that include information and images of animal cruelty. Zines also played a fundamental part by discussing animal rights, factory farming, and the health and environmental effects of diets, often drawing on academic authors. For many listeners, punk rock scenes provided their first encounter with the horrors of slaughterhouses or laboratories, as noted by the comparative religion scholar Sarah M. Pike and vocalist Markus Meißner, especially "before the Internet made documentaries available to everyone." Regarding vegan straight edge activists, Pieslak writes that the "movement had an intense impact on listeners, with the music playing a transformative role". Pike said that it generated an "internal revolution" in them through "the intensity of hardcore music and [its illustrative] lyrics"; the music working on them together with documentaries that reported the harshness of seal hunting or fur farms; or simply the aural experiences "affirmed at a visceral level" the activists' desire for animal liberation.

Reception from the animal rights movement

The reception of punk's activism has varied through the broader animal rights movement, which reflects the "much more diverse" ideological and tactical differences existent within both movements "than they might at first appear." Sociologist and animal rights advocate Donna Maurer positively exemplified vegan straight edge as a movement that includes ethical veganism as part of their collective identity, therefore furthering the cause, but warned that teens who adopt it only to be part of the group can contribute to the free-rider problem. Strategies such as arson and property damage have often been attributed to the youthfulness and punk subcultural affiliation of A.L.F. activists and other related organisations. The more mainstream advocates tend to condemn these tactics and sometimes their relationship with punk. Others have supported them because, in their opinion, they seem to produce more quick changes. Another controversy has been the anti-abortion stance of some of the most religiously committed activists which, in the case of hardcore punk, were influenced by the sanctity of life belief of Krishna Consciousness and hardline.

Anarcho-punk

Background

The association of anarcho-punk and animal rights and environmentalism dates from the 1980s in the United Kingdom. This relationship (and subgenre) arises in the context of political upheaval, with a conservative government that waged war against Argentina (1982) and would eventually deploy nuclear missiles in the country. Anarcho-punk tried to restore punk rock's original objective of a subversive change in the world, countering the "disappointment, self-destruction, and commercial corruption" that permeated its key first-wave bands, and instead abiding by a devoted do-it-yourself ethic and philosophical anarchism. Anarcho-punk bands, which at first were widely pacifists, called to live consciously and to engage in activism; while some like Discharge and Crass emphasised their anti-war positions, others focused on animal rights such as Flux of Pink Indians and Conflict.

Journalist Nora Kusche states that anarcho-punk was the first music genre that made animal rights activism one of its main characteristics. Some punks, most remarkably Joe Strummer of the Clash, were already vegetarians before the establishment of this movement.

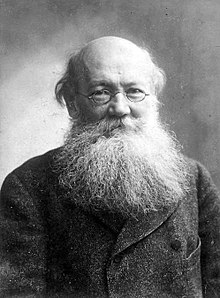

Researcher Aragorn Eloff notes that throughout the history of anarchism there had been some strands that criticised speciesism and embraced plant-based diets, but none had done so with such militancy as anarcho-punk in the 1980s. This was particularly true in its British political tradition.

Characteristics

In the anarchist DIY scenes, one of the most notable demonstrations of the punk lifestyle is a vegetarian or vegan diet. The anarchist philosophy of punk, which favoured action rather than a formal political organisation, was expressed in punks mobilising as hunt saboteurs (whose size was "swelled" by them), raising funds for activist groups and circulating British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection's propaganda. Images of animal testing were commonly exhibited in album covers, stickers, patches and buttons. An already well-established animal rights counterculture inspired some of these strategies, including leafleting at gigs. Kusche highlights that hunting was traditionally linked to the British aristocracy who then were disrupted by the "scruffy, antisocial" punks.

During this period there was also a proliferation of punk zines that discussed animal rights and ecological practices of consumption. The scholars Russ Bestley and Rebecca Binns argue that the early establishment of animal rights in anarcho-punk led to a form of "two-way dialogue" between bands and participants instead of a "top-down" ideological imposition, which became more the case with other developments.

Many traditional British anarchists differed in several ways from anarcho-punk, considering their interest in the Animal Liberation Front (A.L.F.), the counterculture of the punk underground and other concerns as "at best secondary and at worst irrelevant." Likewise, punks found many of the intellectual debates around anarchist politics and, initially, the violence supported by revolutionary traditionalists equally alienating. Although the separation was not unbridgeable, the tensions remained unresolved.

Establishment

An antecedent of this association is the 1979 song "Time Out" by the band Crass, initiators of anarcho-punk, in which they compare the human and animal fleshes. The band Flux of Pink Indians pioneered this trend with their 1981 EP Neu Smell. During their career, Flux gave out thousands of leaflets on vivisection and other subjects at their gigs. In the following years, numerous anarcho-punk bands composed songs promoting animal rights and sometimes made it the principal topic, encompassing vegetarianism, anti-vivisection and opposition to hunting. Furthermore, they would often include information and images of animal cruelty in their records. The most important advocates of vegetarianism and animal rights were the group Conflict, who aligned themselves with the Animal Liberation Front (A.L.F.) This band made a "call to arms" against different institutions, including slaughterhouses, and projected video footage of these while they played. The title of their 1983 song "Meat Means Murder" turned into a slogan which quickly propagated through the punk scene; articles on the topic appeared on fanzines, even on American (Flipside and Maximumrocknroll) and Australian ones. Their follow-up single To a Nation of Animal Lovers (1983) featured Steve Ignorant of Crass as co-vocalist and included illustrated vivisection essays in addition to addresses of scientists, food producers and fur farms.

Early anarcho-punk bands such as Amebix, Antisect, Dirt, Exit-Stance, Liberty, Lost Cherrees, Poison Girls, Rudimentary Peni, and Subhumans all wrote songs dealing with animal rights issues as well, as did non-political bands such as the Business. Other remarkable works dedicated to the cause were the compilation albums of bands The Animals Packet (1983), organised by Chumbawamba, and This is the A.L.F. (1989), organised by Conflict and which was described in a retrospective review as "one of the most crucial anarcho-punk compilations of the '80s (and beyond)". American political bands of the early 1980s such as MDC and Crucifix, both from California and influenced by Crass, also promoted vegetarianism.

Sociologist Peter Webb ascribed the growth of vegan and vegetarian cafés, organic food suppliers, and A.L.F. and Hunt Saboteurs Association increasing recruitment in Bristol through the first half of the 1980s to its anarcho-punk scene. Several members of political and anarcho-punk bands engaged in direct action activism, for example one member of Polemic Attack from Surrey was imprisoned for raiding an animal laboratory and two members of Anti-System from Bradford for destroying butcher shops and breaking into an abattoir, while the members of Wartoys (Manchester), Virus (Dorset), Polemic Attack, Disorder (Bristol), and Icons of Filth (Wales) all reported to have been hunt saboteurs, the last of whom also made songs against the meat industry and whose vocalist, Stig Sewell, staunchly supported the A.L.F.

In the mid- to late 1980s, the stripped-down and coarse style of anarcho-punk mixed with different subgenres of heavy metal and brought forth crust punk and grindcore, which shared its emphasis on political and animal rights issues. Early grindcore bands such as Napalm Death, Agathocles and Carcass made animal rights one of their primary lyrical themes. Early crust punk bands including Nausea, Electro Hippies and Extreme Noise Terror also advocated vegetarian lifestyles.

In Spain, the anarchist ska punk band Ska-P, formed in 1994, have written several songs criticising animal abuse and endorsed animal rights organisations.

In 2018, Gerfried Ambrosch of the University of Graz called the Canadian anarcho-punk band Propagandhi "the most renowned contemporary vegan punk band".

Impact

Some authors credit the anarcho-punk scene originated by Crass as the introduction of diverse concepts and counter-cultural practices in popular culture, including those related to animal rights. Eloff stated that the sudden growth of animal liberation theory and practice within anarchism since the 1980s, which also developed into philosophies such as veganarchism, was most probably caused by the anarcho-punk subculture. According to author John King, the animal stance of anarcho-punk spread through all areas of punk, especially the traveller, hardcore, straight edge, and folk-punk scenes. Despite this, writer and musician Andy Martin of the influential band the Apostles was not as enthusiastic, stating in 2014 that "Dave Morris and Helen Steel, for example, have achieved more for the campaign against McDonald's than every punk band there has ever been. This is not to unduly berate punk bands, but they must be regarded in the correct perspective..."

Several animal rights activists such as Rod Coronado, Craig Rosebraugh, Isa Chandra Moskowitz, and David J. Wolfson were initially inspired by anarcho-punk bands.

Straight edge and hardcore punk

Characteristics

Beyond the basic tenets of straight edge (complete abstention from alcohol, tobacco and any recreational drug), its participants can lead their lifestyles freely, but an investigation by Ross Haenfler of the University of Mississippi revealed some underlying values across the movement: healthy living, improving one's and others' lives, commitment to straight edge, refraining from casual sex, and involvement in progressive causes. Among the last, two of the most adopted are animal rights and vegetarian lifestyles, which many see as a logical extension of living a positive, non-exploitative lifestyle and equate the harm and immorality of drugs with animal products. Many straight edge activists credit their empathy towards animal suffering and their actions to stop it to the permanent state of consciousness that their sober lifestyle gives them.

Straight edge, as most subcultures, is not inherently political but its participants seek to "remoralise" dominant culture through their individual acts of resistance. However, it often serves as a bridge to further political involvement, especially in social justice and progressive causes. The scholar Simon J. Bronner observes the lack of political homogeneity within the ideology, noting that there have been radical, religious, anarchist, and conservative straight edge bands, sometimes-tensely-coexisting in local scenes. For example, Earth Crisis, Vegan Reich and Chokehold all advocate veganism and sobriety, but disagree on other issues. Sociologist William Tsitsos pointed out that some of the most influential American straight edge bands that espoused animal rights focused only on personal morality, even when referring to corporations, while some of their European counterparts saw these lifestyles as part of a larger left-wing challenge against capitalism. He argues that, to a large extent, this was the result of the neoliberal and welfare politics that respectively dominated these territories.

The most controversial offshoot that advocated animal rights was hardline, a biocentric militant ideology that combines veganism, revolutionary politics and an Abrahamic view of the natural order, thus abjuring homosexuality and abortion. Hardline was largely marginalised and remained a fringe phenomenon. The sacredness of life belief introduced by hardline and Krishna Consciousness did not only embrace animals, but also unborn children. This influenced the anti-abortion stance of some of the most religiously committed animal rights activists and created a rift with those who supported it.

Influences and first contacts

In the mid- to late 1980s, American hardcore punk music and particularly its subculture straight edge began to get involved in animal rights and environmentalism. Journalist Brian Peterson attributes diverse influences on this relationship beyond anarcho-punk: the post-hardcore band Beefeater, the 1985 album Meat Is Murder by British post-punk band the Smiths, the Hare Krishna tradition, and the vegetarian rapper KRS-One. On the other hand, Pike notes two origins for the activists that would later emerge from the scene: the political one, which started with the arrival of the Animal Liberation Front from England, and the religious one, influenced by the Hare Krishna faith. Pioneering this trend were the 1986 songs "Do Unto Others" by Cro-Mags, a band with Hare Krishna members, and "Free At Last" by Youth of Today, straight edgers, both criticising slaughterhouses in a verse.

Establishment

After those first contacts, works such as Diet for a New America (1987) by John Robbins and Animal Liberation (1975) by Peter Singer increasingly began to circulate between the members of the scene, influencing bands and zines. By this time Youth of Today had become the most popular straight edge group, propagating the youth crew subculture, and included the pro-vegetarian song "No More" and a recommendation of vegetarian literature in their 1988 album We're Not in This Alone. Several straight edge bands followed this trend, including Insted and Gorilla Biscuits. In the early 1990s, the straight edge offshoot krishnacore was developed, which among its principles includes vegetarianism, centred on the bands Shelter (formed by two ex members of Youth of Today) and 108. Haenfler estimates that at this time three out of four straight edgers in Denver, Colorado were vegetarians and that among them were many vegans. However, it did not take long before the new vocal vegetarians received a backlash from punks who considered these issues private.

Analogously, in the late 1980s, the hardcore punk subgenre powerviolence was established in California, featuring politically militant lyrics that also address animal rights. One of its most notable bands are Dropdead, who took cues from anarcho-punk and a strong animal activist stance.

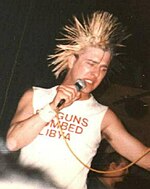

Propagation and militance

The American band Vegan Reich, formed in the anarcho-punk community, released their self-titled EP in 1990 along with a manifesto that ushered in hardline, a biocentric, militant, vegan, anti-drugs, and sexually conservative ideology. Vegan Reich frontman Sean Muttaqi stated he started the band to "spread a militant animal liberation message," but ended up disillusioned with hardliners as they were "all-consumed with minute details or inward shit" by the end of his band in 1993. The hardline scene was small, had few associated acts (including Raid and Statement), and its principles on sexuality and abortion marginalised them to a large extent, but its stances on animal rights were innovative and helped to push veganism, direct action and increase awareness on animal liberation in hardcore punk. Vegan Reich also infused a more metal sound into straight edge.

The debates arising from the new moral tendencies in hardcore prompted animal rights to become predominant in the 1990s. Animal groups such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) began to set up stalls at shows, distributing free literature. These organisations paid for advertisement in zines, some of which devoted their entire content to discuss these causes. Consequently, the association between straight edge and vegetarianism or veganism soon permeated the whole scene and gave rise to a predominantly militant branch centred on veganism: vegan straight edge. One of its pioneering bands was Chokehold from Ontario, Canada, but the ideology was largely popularised and radicalised by Earth Crisis from Syracuse, New York, whose lyrics from their 1995 debut album Destroy the Machines "read like passages from Earth First!, Animal Liberation Front, and Earth Liberation Front direct-action essays." Other notable American vegan straight edge bands during the 1990s were Birthright (Indiana), Culture (Florida), Day of Suffering (North Carolina), Green Rage (New York), Morning Again (Florida), and Warcry (Indiana). By and large, their style was a blend of hardcore punk and extreme metal known as metalcore. The vegan straight edge record label Catalyst Records was founded in Indiana in the early 1990s as well.

Vegan straight edge soon influenced bands from many countries, including Sweden (Refused and Abhinanda), Portugal (New Winds), and Brazil (Point of No Return). In Belgium, straight edge bands such as ManLiftingBanner also advocated vegetarian diets and the Ieperfest vegan hardcore festival was founded in 1993, which would also influence the creation of the Czech vegan Fluff Fest in 2000. In Umeå, the city of Refused and Abhinanda, the number of 15-year-old vegetarians increased to 16% in 1996. Since the mid-1990s, the hardcore scene of São Paulo, Brazil has been highly organised, politicised and involved in animal rights by a collective that incorporated straight edge, anarchism, and the Hare Krishna tradition. One of its branches established the Verdurada drug and meat free festival in 1996, in which a vegan dinner is served at the end to the attendees. A portion of the Israeli hardcore scene intertwined straight edge, animal rights and anarchism at this period as well.

Inspired by these developments, some young people joined radical groups for animal rights and environmentalism such as the Animal Liberation Front (A.L.F.), Animal Defense League (A.D.L.), Sea Shepherd Conservation Society and Earth First! An increase in Animal Liberation Front activism in North America corresponds with the rise of vegan straight edge and hardline bands through the 1990s. The majority of animal rights activists imprisoned in the late 1990s and early 2000s were involved in hardcore punk. Despite the preponderance of this association, some people in the scene felt that militancy was taken to the extreme and they often responded reactionarily. Direct action methods were especially debated for the aggression and sometimes criminality they meant.

In the late 1990s, several vegan straight edge bands had split up and soon the ideology took a back seat in the American hardcore subculture, but its impact on the scene has lasted and become "almost inextricably linked" to it.

Impact

Journalist Will Potter affirms that the hardcore subculture "was even more influential" for activists than its British predecessor, with both having "had a formative, lasting impact on" the radical animal rights and environmental movements. Peterson states that the impact of animal rights on hardcore is felt not only in the scene, but also in the collective consciousness and many activists who developed there. Dylan Clark of the University of Toronto wrote that straight edge's advocacy of veganism ultimately fed it into the entire punk spectrum. Several animal rights activists such as Peter Daniel Young, several members of Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty 7 (SHAC 7), and Walter Bond were initially inspired by straight edge bands.

Other manifestations

In Germany, the punk zine Ox-Fanzine was founded in 1989 and began publishing vegan cookbooks. In later years, there has been an influx of punk-themed cookbooks published by large publishing houses, including How It All Vegan (1999) by Sarah Kramer and Tanya Barnard, and Vegan with a Vengeance (2005) by Isa Chandra Moskowitz. Several punks have set up vegetarian restaurants across the United States after noticing the lack of catering towards them. Cosmetic and clothing companies also began to serve to their new punk-vegan niche market, including lines by Manic Panic (company started by former members of Blondie) and Kat Von D.

Since 2001, Vans Warped Tour has been affiliated with PETA, including food vendors that distribute animal rights information. Other large punk festivals such as Rebellion in 2011 have turned their backstage caterings entirely vegetarian.

The ska-punk band Goldfinger, formed in 1994, started as a "fun" project but since their fourth album, Open Your Eyes (2002), their frontman and producer John Feldmann became a member of PETA and put animal rights at the forefront of their music.

In Spain and some Latin American countries, several punk bands have written songs against bullfighting.