| Foot-and-mouth disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hoof-and-mouth disease, Aphthae epizooticae, Apthous fever |

| |

| Ruptured oral blister in a diseased cow | |

| Specialty | Veterinary medicine |

Foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) or hoof-and-mouth disease (HMD) is an infectious and sometimes fatal viral disease that affects cloven-hoofed animals, including domestic and wild bovids. The virus causes a high fever lasting two to six days, followed by blisters inside the mouth and near the hoof that may rupture and cause lameness.

FMD has very severe implications for animal farming, since it is highly infectious and can be spread by infected animals comparatively easily through contact with contaminated farming equipment, vehicles, clothing, and feed, and by domestic and wild predators. Its containment demands considerable efforts in vaccination, strict monitoring, trade restrictions, quarantines, and the culling of both infected and healthy (uninfected) animals.

Susceptible animals include cattle, water buffalo, sheep, goats, pigs, antelope, deer, and bison. It has also been known to infect hedgehogs and elephants; llamas and alpacas may develop mild symptoms, but are resistant to the disease and do not pass it on to others of the same species. In laboratory experiments, mice, rats, and chickens have been artificially infected, but they are not believed to contract the disease under natural conditions. Cattle, Asian and African buffalo, sheep, and goats can become carriers following an acute infection, meaning they are still infected with a small amount of virus but appear healthy. Animals can be carriers for up to 1–2 years and are considered very unlikely to infect other animals, although laboratory evidence suggests that transmission from carriers is possible.

Humans are only extremely rarely infected by foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV). (Humans, particularly young children, can be affected by hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMDV), which is often confused for FMDV. Similarly, HFMDV is a viral infection belonging to the Picornaviridae family, but it is distinct from FMDV. HFMDV also affects cattle, sheep, and swine.)

The virus responsible for FMD is an aphthovirus, foot-and-mouth disease virus. Infection occurs when the virus particle is taken into a cell of the host. The cell is then forced to manufacture thousands of copies of the virus, and eventually bursts, releasing the new particles in the blood. The virus is genetically highly variable, which limits the effectiveness of vaccination. The disease was first documented in 1870.

Signs and symptoms

The incubation period for FMD virus has a range between one and 12 days. The disease is characterized by high fever that declines rapidly after two to three days, blisters inside the mouth that lead to excessive secretion of stringy or foamy saliva and to drooling, and blisters on the feet that may rupture and cause lameness. Adult animals may suffer weight loss from which they do not recover for several months, as well as swelling in the testicles of mature males, and cows' milk production can decline significantly. Though most animals eventually recover from FMD, the disease can lead to myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) and death, especially in newborn animals. Some infected ruminants remain asymptomatic carriers, but they nonetheless carry the virus and may be able to transmit it to others. Pigs cannot serve as asymptomatic carriers.

Subclinical Infection

Subclinical (asymptomatic) infections can be classified as neoteric or persistent based on when they occur and whether the animal is infectious. Neoteric subclinical infections are acute infections, meaning they occur soon after an animal is exposed to the FMD virus (about 1 to 2 days) and last about 8 to 14 days. Acute infections are characterized by a high degree of replicating virus in the pharynx. In a neoteric subclinical infection, the virus remains in the pharynx and does not spread into the blood as it would in a clinical infection. Although animals with neoteric subclinical infections do not appear to have disease, they shed substantial amounts of virus in nasal secretions and saliva, so they are able to transmit the FMD virus to other animals. Neoteric subclinical infections often occur in vaccinated animals but can occur in unvaccinated animals as well.

Persistent subclinical infection (also referred to as a carrier state) occurs when an animal recovers from an acute infection but continues to have a small amount of replicating virus present in the pharynx. Cattle, buffalo, sheep, and goats can all become carriers, but pigs cannot. Animals can become carriers following acute infections with or without symptoms. Both vaccinated and unvaccinated animals can become carriers. Transmission of the FMD virus from carriers to susceptible animals is considered very unlikely under natural conditions and has not been conclusively demonstrated in field studies.

However, in an experiment where virus was collected from the pharynx of carrier cattle and inserted in the pharynx of susceptible cattle, the susceptible cattle became infected and developed characteristic blisters in the mouth and on the feet. This supports the theory that while the likelihood of a carrier spreading FMD is quite low, it is not impossible. It is not fully understood why ruminants but not pigs can become carriers or why some animals develop persistent infection while others do not. Both are areas of ongoing study.

Because vaccinated animals can become carriers, the waiting period to prove FMD-freedom is longer when vaccination rather than slaughter is used as an outbreak-control strategy. As a result, many FMD-free countries are resistant to emergency vaccination in case of in outbreak out of concern for the serious trade and economic implications of a prolonged period without FMD-free status.

Although the risk of transmission from an individual FMD carrier is considered to be very low, there are many carriers in FMD-endemic regions, possibly increasing the number of chances for carrier transmission to occur. Also, it can be difficult to determine if an asymptomatic infection is neoteric or persistent in the field, as both would be apparently healthy animals that test positive for the FMD virus. This fact complicates disease control, as the two types of subclinical infections have significantly different risks of spreading disease.

Cause

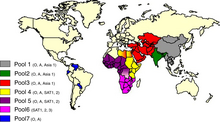

Of the seven serotypes of this virus, A, C, O, Asia 1, and SAT3 appear to be distinct lineages; SAT 1 and SAT 2 are unresolved clades. The mutation rate of the protein-encoding sequences of strains isolated between 1932 and 2007 has been estimated to be 1.46 × 10−3 substitutions/site/year, a rate similar to that of other RNA viruses. The most recent common ancestor appears to have evolved about 481 years ago (early 16th century). This ancestor then diverged into two clades which have given rise to the extant circulating Euro-Asiatic and South African. SAT 1 diverged first 397 years ago, followed by sequential divergence of serotype SAT 2 (396 years ago), A (147 years ago), O (121 years ago), Asia 1 (89 years ago), C (86 years ago), and SAT 3 (83 years ago). Bayesian skyline plot reveals a population expansion in the early 20th century that is followed by a rapid decline in population size from the late 20th century to the present day. Within each serotype, there was no apparent periodic, geographic, or host species influence on the evolution of global FMD viruses. At least seven genotypes of serotype Asia 1 are known.

Transmission

The FMD virus can be transmitted in a number of ways, including close-contact, animal-to-animal spread, long-distance aerosol spread and fomites, or inanimate objects, typically fodder and motor vehicles. The clothes and skin of animal handlers such as farmers, standing water, and uncooked food scraps and feed supplements containing infected animal products can harbor the virus, as well. Cows can also catch FMD from the semen of infected bulls. Control measures include quarantine and destruction of both infected and healthy (uninfected) livestock, and export bans for meat and other animal products to countries not infected with the disease.

There is significant variation in both susceptibility to infection and ability to spread disease between different species, virus strains, and transmission routes. For example, cattle are far more vulnerable than pigs to infection with aerosolized virus, and infected pigs produce 30 times the amount of aerosolized virus compared to infected cattle and sheep. Also, pigs are particularly vulnerable to infection through the oral route. It has been demonstrated experimentally that FMD can be spread to pigs when they eat commercial feed products contaminated by the FMD virus. Also, the virus can remain active for extended periods of time in certain feed ingredients, especially soybean meal. Feed biosecurity practices have become an important area of study since a 2013 outbreak of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus (PEDV) in the US, thought to be introduced through contaminated feed.

Just as humans may spread the disease by carrying the virus on their clothes and bodies, animals that are not susceptible to the disease may still aid in spreading it. This was the case in Canada in 1952, when an outbreak flared up again after dogs had carried off bones from dead animals. Wolves are thought to play a similar role in the former Soviet Union.

Daniel Rossouw Kannemeyer (1843–1925) published a note in the Transactions of the South African Philosophical Society volume 8 part 1 in which he links saliva-covered locusts with the spread of the disease.

Transmission of the FMD virus is possible before an animal has apparent signs of disease, a factor that increases the risk that significant spread of the virus has occurred before an outbreak is detected. A 2011 experiment measured transmission timing in cattle infected with serotype O virus by exposing susceptible cattle in 24-hour increments. It estimated the infectious period of the infected cattle to be 1.7 days, but showed the cattle were only infectious for a few hours before they developed fevers or classic FMD lesions. The authors also showed that the infectious period would have been estimated to be much higher (4.2 to 8.2 days) if detection of virus had been used as a substitute for infectiousness. A similar 2016 experiment using serotype A virus exposed susceptible pigs to infected pigs for 8 hour periods and found that pigs were able to spread disease for a full day before developing signs of disease. Analysis of this experimental data estimated the infectious period to be approximately 7 days. Again, the study showed that detection of virus was not an accurate substitution for infectiousness. An accurate understanding of the parameters of infectiousness is an important component of building epidemiological models which inform disease control strategies and policies.

Infecting humans

Humans can be infected with FMD through contact with infected animals, but this is extremely rare. Some cases were caused by laboratory accidents. Because the virus that causes FMD is sensitive to stomach acid, it cannot spread to humans via consumption of infected meat, except in the mouth before the meat is swallowed. In the UK, the last confirmed human case occurred in 1966, and only a few other cases have been recorded in countries of continental Europe, Africa, and South America. Symptoms of FMD in humans include malaise, fever, vomiting, red ulcerative lesions (surface-eroding damaged spots) of the oral tissues, and sometimes vesicular lesions (small blisters) of the skin. According to a newspaper report, FMD killed two children in England in 1884, supposedly due to infected milk.

Another viral disease with similar symptoms, hand, foot and mouth disease, occurs more frequently in humans, especially in young children; the cause, Coxsackie A virus, is different from the FMD virus. Coxsackie viruses belong to the Enteroviruses within the Picornaviridae.

Because FMD rarely infects humans, but spreads rapidly among animals, it is a much greater threat to the agriculture industry than to human health.

Prevention

Like other RNA viruses, the FMD virus continually evolves and mutates, thus one of the difficulties in vaccinating against it is the huge variation between, and even within, serotypes. No cross-protection has been seen between serotypes (a vaccine for one serotype will not protect against any others) and in addition, two strains within a given serotype may have nucleotide sequences that differ by as much as 30% for a given gene. This means FMD vaccines must be highly specific to the strain involved. Vaccination only provides temporary immunity that lasts from months to years.

Currently, the World Organisation for Animal Health recognizes countries to be in one of three disease states with regard to FMD: FMD present with or without vaccination, FMD-free with vaccination, and FMD-free without vaccination.[36] Countries designated FMD-free without vaccination have the greatest access to export markets, so many developed nations, including Canada, the United States, and the UK, work hard to maintain their current status. Some countries such as Brazil and Argentina, which have large beef-exporting industries, practise vaccination in some areas, but have other vaccination-free zones.

Reasons cited for restricting export from countries using FMD vaccines include, probably most importantly, routine blood tests relying on antibodies cannot distinguish between an infected and a vaccinated animal, which severely hampers screening of animals used in export products, risking a spread of FMD to importing countries. A widespread preventive vaccination would also conceal the existence of the virus in a country. From there, it could potentially spread to countries without vaccine programs. Lastly, an animal infected shortly after being vaccinated can harbor and spread FMD without showing symptoms itself, hindering containment and culling of sick animals as a remedy.

Many early vaccines used dead samples of the FMD virus to inoculate animals, but those early vaccines sometimes caused real outbreaks. In the 1970s, scientists discovered that a vaccine could be made using only a single key protein from the virus. The task was to produce enough quantities of the protein to be used in the vaccination. On June 18, 1981, the US government announced the creation of a vaccine targeted against FMD, the world's first genetically engineered vaccine.

The North American FMD Vaccine Bank is housed at the United States Department of Agriculture's Foreign Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory at Plum Island Animal Disease Center. The center, located 1.5 mi (2.4 km) off the coast of Long Island, New York, is the only place in the United States where scientists can conduct research and diagnostic work on highly contagious animal diseases such as FMD. Because of this limitation, US companies working on FMD usually use facilities in other countries where such diseases are endemic.

Epidemiology

United States (1870–1929)

The US has had nine FMD outbreaks since it was first recognized on the northeastern coast in 1870; the most devastating happened in 1914. It originated from Michigan, but its entry into the stockyards in Chicago turned it into an epizootic. About 3,500 livestock herds were infected across the US, totaling over 170,000 cattle, sheep, and swine. The eradication came at a cost of US$4.5 million (equivalent to $137 million in 2023).

A 1924 outbreak in California resulted not only in the slaughter of 109,000 farm animals, but also 22,000 deer.

The US had its latest FMD outbreak in Montebello, California, in 1929. This outbreak originated in hogs that had eaten infected meat scraps from a tourist steamship that had stocked meat in Argentina. Over 3,600 animals were slaughtered and the disease was contained in less than a month.

Mexico–U.S. border (1947)

On December 26, 1946, the United States and Mexico jointly declared that FMD had been found in Mexico. Initially, proposals from Texans were for an animal-proof wall, to prevent animals from crossing the border and spreading the disease, but the two countries eventually managed to cooperate in a bilateral effort and eradicated the disease without building a wall. To prevent tension between ranchers and the veterinarians, public broadcasts over the radio and with speakers on trucks were used to inform Mexican ranchers why the U.S. veterinarians were working on their livestock. Ranchers who lost cattle due to being culled by the vets would receive financial compensation. However, the tension remained and resulted in clashes between local citizens and the military-protected U.S. veterinarians. These teams of veterinarians worked from outside the infection zone of the disease and worked their way to the heart of the epidemic. Over 60,000,000 injections were administered to livestock by the end of 1950.

United Kingdom (1967)

In October 1967, a farmer in Shropshire reported a lame sow, which was later diagnosed with FMD. The source was believed to be remains of legally imported infected lamb from Argentina and Chile. The virus spread, and in total, 442,000 animals were slaughtered and the outbreak had an estimated cost of £370 million (equivalent to £8 billion in 2023).

Taiwan (1997)

Taiwan had previous epidemics of FMD in 1913–14 and 1924–29, but had since been spared, and considered itself free of FMD as late as in the 1990s. On the 19th of March 1997, a sow at a farm in Hsinchu, Taiwan, was diagnosed with a strain of FMD that only infects swine. Mortality was high, nearing 100% in the infected herd. The cause of the epidemic was not determined, but the farm was near a port city known for its pig-smuggling industry and illegal slaughterhouses. Smuggled swine or contaminated meat are thus likely sources of the disease.

The disease spread rapidly among swine herds in Taiwan, with 200–300 new farms being infected daily. Causes for this include the high swine density in the area, with up to 6,500 hogs per square mile, feeding of pigs with untreated garbage, and the farms' proximity to slaughterhouses. Other systemic issues, such as lack of laboratory facilities, slow response, and initial lack of a vaccination program, contributed.

A complicating factor is the endemic spread of swine vesicular disease (SVD) in Taiwan. The symptoms are indistinguishable from FMD, which may have led to previous misdiagnosing of FMD as SVD. Laboratory analysis was seldom used for diagnosis, and FMD may thus have gone unnoticed for some time.

The swine depopulation was a massive undertaking, with the military contributing substantial manpower. At peak capacity, 200,000 hogs per day were disposed of, mainly by electrocution. Carcasses were disposed of by burning and burial, but burning was avoided in water resource-protection areas. In April, industrial incinerators were running around the clock to dispose of the carcasses.

Initially, 40,000 combined vaccine doses for the strains O-1, A-24, and Asia-1 were available and administered to zoo animals and valuable breeding hogs. At the end of March, half a million new doses for O-1 and Asia-1 were made available. On the May 3rd, 13 million doses of O-1 vaccine arrived, and both the March and May shipments were distributed free of charge. With a danger of vaccination crews spreading the disease, only trained farmers were allowed to administer the vaccine under veterinary supervision.

Taiwan had previously been the major exporter of pork to Japan, and among the top 15 pork producers in the world in 1996. During the outbreak, over 3.8 million swine were destroyed at a cost of US$6.9 billion (equivalent to $13.1 billion in 2023). The Taiwanese pig industry was devastated as a result, and the export market was in ruins. In 2007, Taiwan was considered free of FMD, but was still conducting a vaccination program, which restricts the export of meat from Taiwan.

United Kingdom (2001)

The epidemic of FMD in the United Kingdom in the spring and summer of 2001 was caused by the "Type O pan Asia" strain of the disease. This episode resulted in more than 2,000 cases of the disease in farms throughout the British countryside. More than six million sheep and cattle were killed in an eventually successful attempt to halt the disease. The county of Cumbria was the most seriously affected area of the country, with 843 cases. By the time the disease was halted in October 2001, the crisis was estimated to have cost Britain £8 billion (equivalent to £17 billion in 2023) to the agricultural and support industries, and to the outdoor industry. What made this outbreak so serious was the amount of time between infection being present at the first outbreak locus, and when countermeasures were put into operation against the disease, such as transport bans and detergent washing of both vehicles and personnel entering livestock areas. The epidemic was probably caused by pigs that had been fed infected rubbish that had not been properly heat-sterilized. Further, the rubbish is believed to have contained remains of infected meat that had been illegally imported to Britain.

China (2005)

In April 2005, an Asia-1 strain of FMD appeared in the eastern provinces of Shandong and Jiangsu. During April and May, it spread to suburban Beijing, the northern province of Hebei, and the Xinjiang autonomous region in northwest China. On 13 May, China reported the FMD outbreak to the World Health Organization and the OIE. This was the first time China has publicly admitted to having FMD. China is still reporting FMD outbreaks. In 2007, reports filed with the OIE documented new or ongoing outbreaks in the provinces of Gansu, Qinghai and Xinjiang. This included reports of domestic yak showing signs of infection. FMD is endemic in pastoral regions of China from Heilongjiang Province in the northeast to Sichuan Province and the Tibetan Autonomous region in the southwest. Chinese domestic media reports often use a euphemism "Disease Number Five" (五号病 wǔhàobìng) rather than FMD in reports because of the sensitivity of the FMD issue. In March 2010, Southern Rural News (Nanfang Nongcunbao), in an article "Breaking the Hoof and Mouth Disease Taboo", noted that FMD has long been covered up in China by referring to it that way. FMD is also called canker (口疮, literally "mouth ulcers" kǒuchuāng) or hoof jaundice (蹄癀 tíhuáng) in China, so information on FMD in China can be found online using those words as search terms. One can find online many provincial orders and regulations on FMD control antedating China's acknowledgment that the disease existed in China, for example Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region 1991 regulation on preventing the spread of Disease No.5.

United Kingdom (2007)

An infection of FMD in the United Kingdom was confirmed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, on 3 August 2007, on farmland located in Normandy, Surrey. All livestock in the vicinity were culled on 4 August. A nationwide ban on the movement of cattle and pigs was imposed, with a 3-km (1.9-mi) protection zone placed around the outbreak sites and the nearby virus research and vaccine production establishments, together with a 10-km (6.2-mi) increased surveillance zone.

On 4 August, the strain of the virus was identified as a "01 BFS67-like" virus, one linked to vaccines and not normally found in animals, and isolated in the 1967 outbreak. The same strain was used at the nearby Institute for Animal Health and Merial Animal Health Ltd at Pirbright, 2.5 miles (4.0 km) away, which is an American/French-owned BSL-4 vaccine manufacturing facility, and was identified as the likely source of infection.

On 12 September, a new outbreak of the disease was confirmed in Egham, Surrey, 19 km (12 mi) from the original outbreak, with a second case being confirmed on a nearby farm on 14 September.

These outbreaks caused a cull of all at-risk animals in the area surrounding Egham, including two farms near the famous four-star hotel Great Fosters. These outbreaks also caused the closure of Windsor Great Park due to the park containing deer; the park remained closed for three months. On 19 September 2007, a suspected case of FMD was found in Solihull, where a temporary control zone was set up by Defra.

Japan and Korea (2010–2011)

In April 2010, a report of three incursions of FMD in Japan and South Korea led the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to issue a call for increased global surveillance. Japan veterinary authorities confirmed an outbreak of type O FMD virus, currently more common in Asian countries where FMD is endemic.

South Korea was hit by the rarer type A FMD in January, and then the type O infection in April. The most serious case of foot-and-mouth outbreak in South Korea's history started in November 2010 in pig farms in Andong city of Gyeongsangbuk-do, and has since spread in the country rapidly. More than 100 cases of the disease have been confirmed in the country so far, and in January 2011, South Korean officials started a mass cull of approximately 12%, or around three million in total, of the entire domestic pig population, and 107,000 of three million cattle of the country to halt the outbreak. According to the report based on complete 1D gene sequences, Korean serotype A virus was linked with those from Laos. Korean serotype O viruses were divided into three clades and were closely related to isolates from Japan, Thailand, the UK, France, Ireland, South Africa, and Singapore, as well as Laos.

On 10 February 2011, North Korea reported an outbreak affecting pigs in the region around Pyongyang, by then ongoing since at least December 2010. Efforts to control the outbreak were hampered by illicit sales of infected meat.

Indonesia (2022)

After being eradicated there in 1986, FMD was again detected in Indonesia in May 2022. The Australian government has offered its assistance but remains unconcerned, considering the risk to the country's biosecurity to be low. The Department of Agriculture (DAWE) is the responsible body and has been monitoring the situation. DAWE has determined there is only a low risk and has stockpiled vaccines since 2004 anyhow.

In response to the Indonesian outbreak, Australian authorities began checking parcels and baggage from Indonesia and China. Disinfectant floormats were also installed at Australian airports to clean footwear. The Albanese Government rejected calls by opposition parties to close the border to travel from Indonesia. In addition, New Zealand authorities have banned travellers from Indonesia from bringing meat products, screened baggage from Indonesia, and installed floor mats. New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and Biosecurity Minister Damien O'Connor have expressed concern about the impact of foot and mouth disease on New Zealand's substantial cattle, sheep and pig populations as well as wildlife.

History

The cause of FMD was first shown to be viral in 1897 by Friedrich Loeffler. He passed the blood of an infected animal through a Chamberland filter and found the collected fluid could still cause the disease in healthy animals.

FMD occurs throughout much of the world, and while some countries have been free of FMD for some time, its wide host range and rapid spread represent cause for international concern. After World War II, the disease was widely distributed throughout the world. In 1996, endemic areas included Asia, Africa, and parts of South America; as of August 2007, Chile is disease-free, and Uruguay and Argentina have not had an outbreak since 2001. In May 2014, the FAO informed that Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru were "just one step away" from eradication;[73] North America and Australia have been free of FMD for many years. New Zealand has never had a case of foot-and-mouth disease. Most European countries have been recognized as disease-free, and countries belonging to the European Union have stopped FMD vaccination.

However, in 2001, a serious outbreak of FMD in Britain resulted in the slaughter of many animals, the postponing of the general election for a month, and the cancellation of many sporting events and leisure activities, such as the Isle of Man TT. Due to strict government policies on sale of livestock, disinfection of all persons leaving and entering farms, and the cancellation of large events likely to be attended by farmers, a potentially economically disastrous epizootic was avoided in Ireland, with just one case recorded in Proleek, County Louth. As one result, the Animal Health Act 2002 was designed by Parliament to provide the regulators with more powers to deal with FMD.

In August 2007, FMD was found at two farms in Surrey, England. All livestock were culled and a quarantine erected over the area. Two other suspected outbreaks have occurred since, although these seem now not to be related to FMD. The only reported case in 2010 was a false alarm from GIS Alex Baker, as proven false by the Florida Farm and Agricultural Department, and quarantine/slaughter of cattle and pigs was confirmed from Miyazaki Prefecture in Japan in June after three cows tested positive. Some 270,000 cattle have been ordered slaughtered following the disease's outbreak.

In 2022, the disease was once again seen in cattle in Indonesia. Other countries are worried that it might spread to their countries soon.

Ethical considerations

Great Britain's response to the 2001 outbreak of foot and mouth disease was a controversial policy of culling all animals within 3 km of an infected farm within 48 hours, leading to the slaughter of over 4 million animals. This was stated to be "a response to a desperate situation, not a pre-meditated response to a known, assessed risk". FMD is usually nonfatal to adult animals. Pigs are capable of airborn transmission of the virus in one extreme case 250 km across the English Channel, although not usually more than 10 km. There are no known cases of cattle or sheep spreading the virus beyond 3 km. The 2007 outbreak was caught much earlier, and was able to be contained after culling only 1,578 animals.

For the farmer, culling animals often results in financial devastation with no ability to honor existing contractual arrangements, thus facing the prospective loss of farm, equipment, and future earning potential. Farmers, especially in more traditional systems, may also have emotional attachments to some of the animals. On the ethical side, one must also consider that FMD is a painful disease for the affected animals. The vesicles and blisters are painful in themselves, and restrict both eating and movement. Through ruptured blisters, the animal is also at risk from secondary bacterial infections. Production loss and vaccination in areas where the disease is endemic costs and estimated US$6.5 billion to 21 billion yearly, and controlling outbreaks in countries normally free of it costs and additional >US$1.5 billion per year. This cost is disproportionately borne by some of the poorest countries in the world. Controlling the virus with vaccines is difficult because there are multiple serotypes of the virus which require distinct vaccines. When an outbreak occurs, the virus must be analyzed before the correct vaccine can be identified. Research is ongoing to improve vaccination technology.