Penal transportation was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies became their destination. While the prisoners may have been released once the sentences were served, they generally did not have the resources to return home.

Origin and implementation

Banishment or forced exile from a polity or society has been used as a punishment since at least the 5th century BCE in Ancient Greece. The practice of penal transportation reached its height in the British Empire during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Transportation removed the offender from society, mostly permanently, but was seen as more merciful than capital punishment. This method was used for criminals, debtors, military prisoners, and political prisoners.

Penal transportation was also used as a method of colonization. For example, from the earliest days of English colonial schemes, new settlements beyond the seas were seen as a way to alleviate domestic social problems of criminals and the poor as well as to increase the colonial labour force, for the overall benefit of the realm.

Great Britain and the British Empire

Initially based on the royal prerogative of mercy, and later under English law, transportation was an alternative sentence imposed for a felony. It was typically imposed for offences for which death was deemed too severe. By 1670, as new felonies were defined, the option of being sentenced to transportation was allowed. Depending on the crime, the sentence was imposed for life or for a set period of years. If imposed for a period of years, the offender was permitted to return home after serving their time, but had to make their own way back. Many offenders thus stayed in the colony as free persons, and might obtain employment as jailers or other servants of the penal colony.

England transported an estimated 50,000 to 120,000 convicts and political prisoners, as well as prisoners of war from Scotland and Ireland, to its overseas colonies in the Americas from the 1610s until early in the American Revolution in 1776, when transportation to America was temporarily suspended by the Criminal Law Act 1776 (16 Geo. 3. c. 43). The practice was mandated in Scotland by an act of 1785, but was less used there than in England. Transportation on a large scale resumed with the departure of the First Fleet to Australia in 1787, and continued there until 1868.

Transportation was not used by Scotland before the Act of Union 1707; following union, the Transportation Act 1717 specifically excluded its use in Scotland. Under the Transportation, etc. Act 1785 (25 Geo. 3. c. 46) the Parliament of Great Britain specifically extended the usage of transportation to Scotland. It remained little used under Scots Law until the early 19th century.

In Australia, a convict who had served part of his time might apply for a ticket of leave, permitting some prescribed freedoms. This enabled some convicts to resume a more normal life, to marry and raise a family, and to contribute to the development of the colony.

Historical background

Trend towards more flexibility of sentencing

In England in the 17th and 18th centuries criminal justice was severe, later termed the Bloody Code. This was due to both the particularly large number of offences which were punishable by execution (usually by hanging), and to the limited choice of sentences available to judges for convicted criminals. With modifications to the traditional benefit of clergy, which originally exempted only clergymen from the general criminal law, it developed into a legal fiction by which many common offenders of "clergyable" offences were extended the privilege to avoid execution. Many offenders were pardoned as it was considered unreasonable to execute them for relatively minor offences, but under the rule of law, it was equally unreasonable for them to escape punishment entirely. With the development of colonies, transportation was introduced as an alternative punishment, although legally it was considered a condition of a pardon, rather than a sentence in itself. Convicts who represented a menace to the community were sent away to distant lands. A secondary aim was to discourage crime for fear of being transported. Transportation continued to be described as a public exhibition of the king's mercy. It was a solution to a real problem in the domestic penal system. There was also the hope that transported convicts could be rehabilitated and reformed by starting a new life in the colonies. In 1615, in the reign of James I, a committee of the council had already obtained the power to choose from the prisoners those that deserved pardon and, consequently, transportation to the colonies. Convicts were chosen carefully: the Acts of the Privy Council showed that prisoners "for strength of bodie or other abilities shall be thought fit to be employed in foreign discoveries or other services beyond the Seas".

During the Commonwealth, Oliver Cromwell overcame the popular prejudice against subjecting Christians to slavery or selling them into foreign parts, and initiated group transportation of military and civilian prisoners. With the Restoration, the penal transportation system and the number of people subjected to it, started to change inexorably between 1660 and 1720, with transportation replacing the simple discharge of clergyable felons after branding the thumb. Alternatively, under the second act dealing with Moss-trooper brigands on the Scottish border, offenders had their benefit of clergy taken away, or otherwise at the judge's discretion, were to be transported to America, "there to remaine and not to returne". There were various influential agents of change: judges' discretionary powers influenced the law significantly, but the king's and Privy Council's opinions were decisive in granting a royal pardon from execution.

The system changed one step at a time: in February 1663, after that first experiment, a bill was proposed to the House of Commons to allow the transporting of felons, and was followed by another bill presented to the Lords to allow the transportation of criminals convicted of felony within clergy or petty larceny. These bills failed, but it was clear that change was needed. Transportation was not a sentence in itself, but could be arranged by indirect means. The reading test, crucial for the benefit of clergy, was a fundamental feature of the penal system, but to prevent its abuse, this pardoning process was used more strictly. Prisoners were carefully selected for transportation based on information about their character and previous criminal record. It was arranged that they fail the reading test, but they were then reprieved and held in jail, without bail, to allow time for a royal pardon (subject to transportation) to be organised.

Transportation as a commercial transaction

Transportation became a business: merchants chose from among the prisoners on the basis of the demand for labour and their likely profits. They obtained a contract from the sheriffs, and after the voyage to the colonies they sold the convicts as indentured servants. The payment they received also covered the jail fees, the fees for granting the pardon, the clerk's fees, and everything necessary to authorise the transportation. These arrangements for transportation continued until the end of the 17th century and beyond, but they diminished in 1670 due to certain complications. The colonial opposition was one of the main obstacles: colonies were unwilling to collaborate in accepting prisoners: the convicts represented a danger to the colony and were unwelcome. Maryland and Virginia enacted laws to prohibit transportation in 1670, and the king was persuaded to respect these.

The penal system was also influenced by economics: the profits obtained from convicts' labour boosted the economy of the colonies and, consequently, of England. Nevertheless, it could be argued that transportation was economically deleterious because the aim was to enlarge population, not diminish it; but the character of an individual convict was likely to harm the economy. King William's War (1688–1697) (part of the Nine Years' War) and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14) adversely affected merchant shipping and hence transportation. In the post-war period there was more crime and hence potentially more executions, and something needed to be done. In the reigns of Queen Anne (1702–14) and George I (1714–27), transportation was not easily arranged, but imprisonment was not considered enough to punish hardened criminals or those who had committed capital offences, so transportation was the preferred punishment.

Transportation Act 1717

There were several obstacles to the use of transportation. In 1706 the reading test for claiming benefit of clergy was abolished (6 Ann. c. 9). This allowed judges to sentence "clergyable" offenders to a workhouse or a house of correction. But the punishments that then applied were not enough of a disincentive to commit crime: another solution was needed. The Transportation Act was introduced into the House of Commons in 1717 under the Whig government. It legitimised transportation as a direct sentence, thus simplifying the penal process.

Non-capital convicts (clergyable felons usually destined for branding on the thumb, and petty larceny convicts usually destined for public whipping) were directly sentenced to transportation to the American colonies for seven years. A sentence of fourteen years was imposed on prisoners guilty of capital offences pardoned by the king. Returning from the colonies before the stated period was a capital offence. The bill was introduced by William Thomson, the Solicitor General, who was "the architect of the transportation policy". Thomson, a supporter of the Whigs, was Recorder of London and became a judge in 1729. He was a prominent sentencing officer at the Old Bailey and the man who gave important information about capital offenders to the cabinet.

One reason for the success of this Act was that transportation was financially costly. The system of sponsorship by merchants had to be improved. Initially the government rejected Thomson's proposal to pay merchants to transport convicts, but three months after the first transportation sentences were pronounced at the Old Bailey, his suggestion was proposed again, and the Treasury contracted Jonathan Forward, a London merchant, for the transportation to the colonies. The business was entrusted to Forward in 1718: for each prisoner transported overseas, he was paid £3 (equivalent to £590 in 2023), rising to £5 in 1727 (equivalent to £940 in 2023). The Treasury also paid for the transportation of prisoners from the Home Counties.

The "Felons' Act" (as the Transportation Act was called) was printed and distributed in 1718, and in April twenty-seven men and women were sentenced to transportation. The Act led to significant changes: both petty and grand larceny were punished by transportation (seven years), and the sentence for any non-capital offence was at the judge's discretion. In 1723 an Act was presented in Virginia to discourage transportation by establishing complex rules for the reception of prisoners, but the reluctance of colonies did not stop transportation.

In a few cases before 1734, the court changed sentences of transportation to sentences of branding on the thumb or whipping, by convicting the accused for lesser crimes than those of which they were accused. This manipulation phase came to an end in 1734. With the exception of those years, the Transportation Act led to a decrease in whipping of convicts, thus avoiding potentially inflammatory public displays. Clergyable discharge continued to be used when the accused could not be transported for reasons of age or infirmity.

Women and children

Penal transportation was not limited to men or even to adults. Men, women, and children were sentenced to transportation, but its implementation varied by sex and age. From 1660 to 1670, highway robbery, burglary, and horse theft were the offences most often punishable with transportation for men. In those years, five of the nine women who were transported after being sentenced to death were guilty of simple larceny, an offence for which benefit of clergy was not available for women until 1692. Also, merchants preferred young and able-bodied men for whom there was a demand in the colonies.

All these factors meant that most women and children were simply left in jail. Some magistrates supported a proposal to release women who could not be transported, but this solution was considered absurd: this caused the Lords Justices to order that no distinction be made between men and women. Women were sent to the Leeward Islands, the only colony that accepted them, and the government had to pay to send them overseas. In 1696 Jamaica refused to welcome a group of prisoners because most of them were women; Barbados similarly accepted convicts but not "women, children nor other infirm persons".

Thanks to transportation, the number of men whipped and released diminished, but whipping and discharge were chosen more often for women. The reverse was true when women were sentenced for a capital offence, but actually served a lesser sentence due to a manipulation of the penal system: one advantage of this sentence was that they could be discharged thanks to benefit of clergy while men were whipped. Women with young children were also supported since transportation unavoidably separated them. The facts and numbers revealed how transportation was less frequently applied to women and children because they were usually guilty of minor crimes and they were considered a minimal threat to the community.

The end of transportation

| Criminal Law Act 1776 |

|---|

The outbreak of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) halted transportation to America. Parliament claimed that "the transportation of convicts to his Majesty's colonies and plantations in America ... is found to be attended with various inconveniences, particularly by depriving this kingdom of many subjects whose labour might be useful to the community, and who, by proper care and correction, might be reclaimed from their evil course"; they then passed the Criminal Law Act 1776 (16 Geo. 3. c. 43) "An act to authorize ... the punishment by hard labour of offenders who, for certain crimes, are or shall become liable to be transported to any of his Majesty's colonies and plantations."

| Criminal Law Act 1778 |

|---|

| Criminal Law Act 1779 |

|---|

For the ensuing decade, men were instead sentenced to hard labour and women were imprisoned. Finding alternative locations to send convicts was not easy, and the act was extended twice by the Criminal Law Act 1778 (18 Geo. 3. c. 62) and the Criminal Law Act 1779 (19 Geo. 3. c. 54).

This resulted in a 1779 inquiry by a parliamentary committee on the entire subject of transportation and punishment; initially the Penitentiary Act 1779 was passed, introducing a policy of state prisons as a measure to reform the system of overcrowded prison hulks that had developed, but no prisons were ever built as a result of the act. The Transportation, etc. Act 1784 (24 Geo. 3. Sess. 2. c. 56) and the Transportation, etc. Act 1785 (25 Geo. 3. c. 46) also resulted to help alleviate overcrowding. Both acts empowered the Crown to appoint certain places within his dominions, or outside them, as the destination for transported criminals; the acts would move convicts around the country as needed for labour, or where they could be utilized and accommodated.

The overcrowding situation and the resumption of transportation would be initially resolved by Orders in Council on 6 December 1786, by the decision to establish a penal colony in New South Wales, on land previously claimed for Britain in 1770, but as yet not settled by Britain or any other European power. The British policy toward Australia, specifically for use as a penal colony, within their overall plans to populate and colonise the continent, would differentiate it from America, where the use of convicts was only a minor adjunct to its overall policy. In 1787, when transportation resumed to the chosen Australian colonies, the far greater distance added to the terrible experience of exile, and it was considered more severe than the methods of imprisonment employed for the previous decade. The Transportation Act 1790 (30 Geo. 3. c. 47) officially enacted the previous orders in council into law, stating "his Majesty hath declared and appointed... that the eastern coast of New South Wales, and the islands thereunto adjacent, should be the place or places beyond the seas to which certain felons, and other offenders, should be conveyed and transported ... or other places". The act also gave "authority to remit or shorten the time or term" of the sentence "in cases where it shall appear that such felons, or other offenders, are proper objects of the royal mercy"

| Transportation Act 1824 |

|---|

At the beginning of the 19th century, transportation for life became the maximum penalty for several offences which had previously been punishable by death. With complaints starting in the 1830s, sentences of transportation became less common in 1840 since the system was perceived to be a failure: crime continued at high levels, people were not dissuaded from committing felonies, and the conditions of convicts in the colonies were inhumane. Although a concerted programme of prison building ensued, the Short Titles Act 1896 lists seven other laws relating to penal transportation in the first half of the 19th century.

The system of criminal punishment by transportation, as it had developed over nearly 150 years, was officially ended in Britain in the 1850s, when that sentence was substituted by imprisonment with penal servitude, and intended to punish. The Penal Servitude Act 1853 (16 & 17 Vict. c. 99), long titled "An Act to substitute, in certain Cases, other Punishment in lieu of Transportation,"[54] enacted that with judicial discretion, lesser felonies, those subject to transportation for less than 14 years, could be sentenced to imprisonment with labour for a specific term. To provide confinement facilities, the general change in sentencing was passed in conjunction with the Convict Prisons Act 1853 (16 & 17 Vict. c. 121), long titled "An Act for providing Places of Confinement in England or Wales for Female Offenders under Sentence or Order of Transportation." The Penal Servitude Act 1857 (20 & 21 Vict. c. 3) ended the sentence of transportation in virtually all cases, with the terms of sentence initially being of the same duration as transportation. While transport was greatly reduced following enactment of the 1857 act, the last convicts sentenced to transportation arrived in Western Australia in 1868. During the 80 years of its use to Australia, the number of transported convicts totalled about 162,000 men and women. Over time the alternative terms of imprisonment would be somewhat reduced from their terms of transportation.

Transportation locations

Transportation to North America

From the early 1600s until the American Revolution of 1776, the British colonies in North America received transported British criminals. Destinations were the island colonies of the West Indies and the mainland colonies that became the United States of America.

In the 17th century transportation was carried out at the expense of the convicts or the shipowners. The Transportation Act 1717 allowed courts to sentence convicts to seven years' transportation to America. In 1720, an extension authorized payments by the Crown to merchants contracted to take the convicts to America. The Transportation Act made returning from transportation a capital offence. The number of convicts transported to North America is not verified: John Dunmore Lang has estimated 50,000, and Thomas Keneally has proposed 120,000. Maryland received a larger felon quota than any other province. Many prisoners were taken in battle from Ireland or Scotland and sold into indentured servitude, usually for a number of years. The American Revolution brought transportation to the North American mainland to an end. The remaining British colonies (in what is now Canada) were regarded as unsuitable for various reasons, including the possibility that transportation might increase dissatisfaction with British rule among settlers and/or the possibility of annexation by the United States – as well as the ease with which prisoners could escape across the border.

After the termination of transportation to North America, British prisons became overcrowded, and dilapidated ships moored in various ports were pressed into service as floating gaols known as "hulks". Following an 18th-century experiment in transporting convicted prisoners to Cape Coast Castle (modern Ghana) and the Gorée (Senegal) in West Africa, British authorities turned their attention to New South Wales (in what would become Australia).

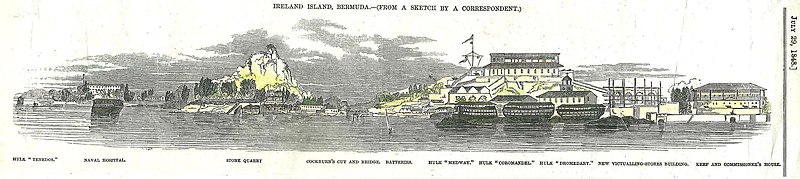

From the 1820s until the 1860s, convicts were sent to the Imperial fortress colony of Bermuda (part of British North America) to work on the construction of the Royal Naval Dockyard and other defence works, including at the East End of the archipelago, where they were accommodated aboard the hulk of HMS Thames at an area still known as "Convict Bay", at St. George's town.

Transportation to Australia

In 1787, the First Fleet, a group of convict ships departed from England to establish the first colonial settlement in Australia, as a penal colony. The First Fleet included boats containing food and animals from London. The ships and boats of the fleet would explore the coast of Australia by sailing all around it looking for suitable farming land and resources. The fleet arrived at Botany Bay, Sydney on 18 January 1788, then moved to Sydney Cove (modern-day Circular Quay) and established the first permanent European settlement in Australia. This marked the beginning of the European colonisation of Australia.

Violent conflict on the Australian frontier between indigenous Australians and the colonists began only months after the First Fleet landed, lasting over a century. Convicts forced to work in the bush on the frontier were sometimes the victims of indigenous attacks, while convicts and ex-convicts also attacked indigenous people in some instances, such as the Myall Creek Massacre. In the Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars, a group of Irish convicts joined the Aboriginal coalition of Eora, Gandangara, Dharug and Tharawal nations in their fight against the colonists.

Norfolk Island, east of the Australian mainland, was a convict penal settlement from 1788 to 1794, and again from 1824 to 1847. In 1803, Van Diemen's Land (modern-day Tasmania) was also settled as a penal colony, followed by the Moreton Bay Settlement (modern Brisbane, Queensland) in 1824. The other Australian colonies were established as "free settlements", as non-convict colonies were known. However, the Swan River Colony (Western Australia) accepted transportation from England and Ireland in 1851, to resolve a long-standing labour shortage.

Two penal settlements were established near modern-day Melbourne in Victoria but both were abandoned shortly after. Later, a free settlement was established and this settlement later accepted some convict transportation.

Until the massive influx of immigrants during the Australian gold rushes of the 1850s, free settlers had been outnumbered by penal convicts and their descendants. However, compared to the British American colonies, Australia received a larger number of convicts.

Convicts were generally treated harshly, forced to work against their will, often doing hard physical labour and dangerous jobs. In some cases they were cuffed and chained in work gangs. The majority of convicts were men, although a significant portion were women. Some were as young as 10 when convicted and transported to Australia. Most were guilty of relatively minor crimes like theft of food/clothes/small items, but some were convicted of serious crimes like rape or murder. Convict status was not inherited by children, and convicts were generally freed after serving their sentence, although many died during transportation or during their sentence.

Convict assignment (sending convicts to work for private individuals) occurred in all penal colonies aside from Western Australia, and can be compared with the practice of convict leasing in the United States.

Transportation from Great Britain and Ireland ended at different times in different colonies, with the last being in 1868, although it had become uncommon several years earlier thanks to the loosening of laws in Britain, changing sentiment in Australia, and groups such as the Anti-Transportation League.

In 2015, an estimated 20% of the Australian population had convict ancestry. In 2013, an estimated 30% of the Australian population (about 7 million) had Irish ancestry – the highest percentage outside of Ireland – thanks partially to historical convict transportation.

Transportation from British India

In British India – including the province of Burma (now Myanmar) and the port of Karachi (now part of Pakistan) – Indian independence activists were penally transported to the Andaman Islands. A penal colony was established there in 1857 with prisoners from the Indian Rebellion of 1857. As the Indian independence movement swelled, so did the number of prisoners who were penally transported.

The Cellular Jail in Port Blair, South Andaman Island, also called Kālā Pānī or Kalapani (Hindi for black waters), was constructed between 1896 and 1906 as a high-security prison with 698 individual cells for solitary confinement. Surviving prisoners were repatriated in 1937. The penal settlement was shut down in 1945. An estimated 80,000 political prisoners were transported to the Cellular Jail[73] which became known for its harsh conditions, including forced labor; prisoners who went on hunger strikes were frequently force-fed.[74]

France

France transported convicts to Devil's Island and New Caledonia in the 19th and early-to-mid 20th centuries. Devil's Island, a French penal colony in Guiana, was used for transportation from 1852 to 1953. New Caledonia became a French penal colony from the 1860s until the end of the transportations in 1897; about 22,000 criminals and political prisoners (most notably Communards) were sent to New Caledonia.

Henri Charrière (16 November 1906 – 29 July 1973) was a French writer, convicted in 1931 as a murderer by the French courts and pardoned in 1970. He wrote the novel Papillon, a semi-autobiographical novel of his incarceration in and escape from a penal colony in French Guiana.

The most significant individual transported prisoner is probably French army officer Alfred Dreyfus, wrongly convicted of treason in a trial in 1894, held in an atmosphere of antisemitism. He was sent to Devil's Island. The case became a cause célèbre known as the Dreyfus Affair, and Dreyfus was fully exonerated in 1906.

The Soviet Union

Unlike normal penal transportation, many Soviet people were transported as criminals in forms of deportation being proclaimed as enemies of people in a form of collective punishment. During the Second World War, the Soviet Union transported up to 1.9 million people from its western republics to Siberia and the Central Asian republics of the Union. Most were persons accused of treasonous collaboration with Nazi Germany, or of Anti-Soviet rebellion. Following death of Joseph Stalin, most of them were rehabilitated. Populations targeted included Volga Germans, Chechens, and Caucasian Turkic populations. The transportations had a twofold objective: to remove potential liabilities from the warfront, and to provide human capital for the settlement and industrialization of the largely underpopulated eastern regions. The policy continued until February 1956, when Nikita Khrushchev in his speech, "On the Personality Cult and Its Consequences", condemned the transportation as a violation of Leninist principles. Whilst the policy itself was rescinded, the transported populations did not begin to return to their original metropoles until after the collapse of the Soviet Union, in 1991.

Modern Russia

The Russian government today still sends their convicts and political prisoners to prisons that echo those of the Soviet Union. The journey to these prisons and labor camps is long and arduous.

Conditions on the Stolypins (specialized train cars) are very poor. In many cases, the Russian penitentiary system utilizes special cars. These cars contain five large compartments and three smaller compartments. The larger car is 3.5 meters squared. The size of the larger car is approximately the same as normal Russian railcar spaces. The larger compartments have six and a half individual sleeping spaces. There are three bunks on each wall and a half bunk that goes between the two middle bunks. The half bunk is not full sized and prevents prisoners from standing up in the car. For food, prisoners are given dehydrated food three times a day and limited amounts of hot water to rehydrate their meals. Bedding is not provided nor are mattresses. During transit, prisoners do not have access to proper medical treatment. The medication that a prisoner would normally take is carried by guards. Transportation routes are often cyclical and prisoners do not know where they are going. This sense of unease and unknowing has been known to increase feelings of isolation. This process can take 3–5 hours which further prolongs travel time. Prisoners have very limited access to toilets while on the trains, about every five to six hours. While the trains are stationary they have no access at all. This can be very difficult as trains often are kept at stations or train depots for extended periods of time.

While traveling to and from train stations, prisoners are transported in vans. While the time spent in vans is usually shorter than the time spent in trains, the conditions are still quite bad. The vans normally have two larger compartments that can fit 10 prisoners. Within the compartments there is a smaller compartment that is used to keep "at risk" prisoners safe. The smaller compartment is known as a stakan and is smaller than 0.5 meter squared.

In addition to poor transit conditions, prisoners are severely limited in their communication with the outside world. Prisoners are denied the right to communicate with their lawyers and families. This can be difficult for their families because they do not know where the prisoner is or what has happened to them.

In popular culture

Performing arts

Penal transportation is a feature of many broadsides, a new type of folk song that developed in eighteenth-century England. A number of these transportation ballads have been collected from traditional singers. Examples include "Van Diemen's Land," "The Black Velvet Band," "The Peeler and the Goat", and "The Fields of Athenry."

Timberlake Wertenbaker's play Our Country's Good is set in 1780s in the first Australian penal colony. In the 1988 play, convicts and Royal Marines arrive aboard a First Fleet ship and settle New South Wales. Convicts and guards interact as they rehearse a theatre production, which the governor had suggested as an alternate form of entertainment instead of watching public hangings.

In the TV show American Gods, episode 7 season 1, for one of a side story Emily Browning is playing Essie that is transported twice in her life, bringing with her in America the Leprechaun legend.

In the TV show, Murdoch Mysteries, episode 6 season 14, "The Ministry of Virtue," Murdoch must investigate the death of a woman who was sentenced to a bridal version of the punishment. Namely, Murdoch learns of "Virtue Girls," British female convicts who have accepted the alternative of agreeing to marry bachelors in Canada instead of being sentenced to prison.

Literature

One of the key characters in Charles Dickens's novel Great Expectations is an escaped convict, Abel Magwitch. Pip helps him in the opening pages of the novel. Magwitch, who had been apprehended shortly after the young Pip had helped him, was thereafter sentenced to transportation for life to New South Wales in Australia. While so exiled, he earned the fortune that he later would use to help Pip. Further, it was Magwitch's desire to see the "gentleman" that Pip had become that motivated him to illegally return to England, which ultimately led to his arrest and death. Great Expectations was published in serial form in 1860–1861. In Dickens's novel Oliver Twist, the Artful Dodger is convicted and transported to Australia.

My Transportation for Life, Indian freedom fighter Veer Savarkar's memoir of his imprisonment, is set in the British Cellular Jail in the Andaman Islands. Savarkar was imprisoned there from 1911 to 1921.

Franz Kafka's story "In der Strafkolonie" ("In the Penal Colony"), published in 1919, was set in an unidentified penal settlement where condemned prisoners were executed by a brutal machine. The work was later adapted for several other media, including an opera by Philip Glass.

The novel Papillon tells the story of Henri Charrière, a French man convicted of murder in 1931 and exiled to the French Guiana penal colony on Devil's Island. A film adaptation of the book was made in 1973, starring Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman.

The British author W. Somerset Maugham set several stories in the French Caribbean penal colonies. In 1935 he had stayed at Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni in French Guiana. His 1939 novel Christmas Holiday and two short stories in 1940's The Mixture as Before were set there, although he "ignored the brutal punishments and painted a pleasant picture of the infamous colony."

Penal transportation, typically to other planets, sometimes appears in works of science fiction. A classic example is The Moon is a Harsh Mistress by Robert Heinlein (1966), in which convicts and political dissidents are transported to lunar colonies in order to grow food for Earth. In Heinlein's book, a sentence of lunar transportation is necessarily permanent, as the long-term physiological effects of the moon's weak surface gravity (about one-sixth that of Earth) leave "loonies" unable to return safely to Earth.