Socialist states based on the Soviet model have used central planning, although a minority such as the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia have adopted some degree of market socialism. Market abolitionist socialism replaces factor markets with direct calculation as the means to coordinate the activities of the various socially owned economic enterprises that make up the economy. More recent approaches to socialist planning and allocation have come from some economists and computer scientists proposing planning mechanisms based on advances in computer science and information technology.

Planned economies contrast with unplanned economies, specifically market economies, where autonomous firms operating in markets make decisions about production, distribution, pricing and investment. Market economies that use indicative planning are variously referred to as planned market economies, mixed economies and mixed market economies. A command economy follows an administrative-command system and uses Soviet-type economic planning which was characteristic of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc before most of these countries converted to market economies. This highlights the central role of hierarchical administration and public ownership of production in guiding the allocation of resources in these economic systems.

Overview

In the Hellenistic and post-Hellenistic world, "compulsory state planning was the most characteristic trade condition for the Egyptian countryside, for Hellenistic India, and to a lesser degree the more barbaric regions of the Seleucid, the Pergamenian, the southern Arabian, and the Parthian empires". Scholars have argued that the Incan economy was a flexible type of command economy, centered around the movement and utilization of labor instead of goods. One view of mercantilism sees it as involving planned economies.

The Soviet-style planned economy in Soviet Russia evolved in the wake of a continuing existing World War I war-economy as well as other policies, known as war communism (1918–1921), shaped to the requirements of the Russian Civil War of 1917–1923. These policies began their formal consolidation under an official organ of government in 1921, when the Soviet government founded Gosplan. However, the period of the New Economic Policy (c. 1921 to c. 1928) intervened before the planned system of regular five-year plans started in 1928. Leon Trotsky was one of the earliest proponents of economic planning during the NEP period. Trotsky argued that specialization, the concentration of production and the use of planning could "raise in the near future the coefficient of industrial growth not only two, but even three times higher than the pre-war rate of 6% and, perhaps, even higher". According to historian Sheila Fitzpatrick, the scholarly consensus was that Stalin appropriated the position of the Left Opposition on such matters as industrialisation and collectivisation.

After World War II (1939–1945) France and Great Britain practiced dirigisme – government direction of the economy through non-coercive means. The Swedish government planned public-housing models in a similar fashion as urban planning in a project called Million Programme, implemented from 1965 to 1974. Some decentralized participation in economic planning occurred across Revolutionary Spain, most notably in Catalonia, during the Spanish Revolution of 1936.

Relationship with socialism

In the May 1949 issue of the Monthly Review titled "Why Socialism?", Albert Einstein wrote:

I am convinced there is only one way to eliminate these grave evils, namely through the establishment of a socialist economy, accompanied by an educational system which would be oriented toward social goals. In such an economy, the means of production are owned by society itself and are utilized in a planned fashion. A planned economy, which adjusts production to the needs of the community, would distribute the work to be done among all those able to work and would guarantee a livelihood to every man, woman, and child. The education of the individual, in addition to promoting his own innate abilities, would attempt to develop in him a sense of responsibility for his fellow-men in place of the glorification of power and success in our present society.

While socialism is not equivalent to economic planning or to the concept of a planned economy, an influential conception of socialism involves the replacement of capital markets with some form of economic planning in order to achieve ex-ante coordination of the economy. The goal of such an economic system would be to achieve conscious control over the economy by the population, specifically so that the use of the surplus product is controlled by the producers. The specific forms of planning proposed for socialism and their feasibility are subjects of the socialist calculation debate.

Computational economic planning

In 1959 Anatoly Kitov proposed a distributed computing system (Project "Red Book", Russian: Красная книга) with a focus on the management of the Soviet economy. Opposition from the Defence Ministry killed Kitov's plan.

In 1971 the socialist Allende administration of Chile launched Project Cybersyn to install a telex machine in every corporation and organization in the economy for the communication of economic data between firms and the government. The data was also fed into a computer-simulated economy for forecasting. A control room was built for real-time observation and management of the overall economy. The prototype-stage of the project showed promise when it was used to redirect supplies around a trucker's strike, but after CIA-backed Augusto Pinochet led a coup in 1973 that established a military dictatorship under his rule the program was abolished and Pinochet moved Chile towards a more liberalized market economy.

In their book Towards a New Socialism (1993), the computer scientist Paul Cockshott from the University of Glasgow and the economist Allin Cottrell from Wake Forest University claim to demonstrate how a democratically planned economy built on modern computer technology is possible and drives the thesis that it would be both economically more stable than the free-market economies and also morally desirable.

Cybernetics

The use of computers to coordinate production in an optimal fashion has been variously proposed for socialist economies. The Polish economist Oskar Lange (1904–1965) argued that the computer is more efficient than the market process at solving the multitude of simultaneous equations required for allocating economic inputs efficiently (either in terms of physical quantities or monetary prices).

In the Soviet Union, Anatoly Kitov had proposed to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union a detailed plan for the re-organization of the control of the Soviet armed forces and of the Soviet economy on the basis of a network of computing centers in 1959. Kitov's proposal was rejected, as later was the 1962 OGAS economy management network project. Soviet cybernetician, Viktor Glushkov argued that his OGAS information network would have delivered a fivefold savings return for the Soviet economy over the first fifteen-year investment.

Salvador Allende's socialist government pioneered the 1970 Chilean distributed decision support system Project Cybersyn in an attempt to move towards a decentralized planned economy with the experimental viable system model of computed organisational structure of autonomous operative units through an algedonic feedback setting and bottom-up participative decision-making in the form of participative democracy by the Cyberfolk component.

Fictional portrayals

The 1888 novel Looking Backward by Edward Bellamy depicts a fictional planned economy in a United States around the year 2000 which has become a socialist utopia.

The World State in Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932) and Airstrip One in George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) provide fictional depictions of command economies, albeit with diametrically opposed aims. The former is a consumer economy designed to engender productivity while the latter is a shortage economy designed as an agent of totalitarian social control. Airstrip One is organized by the euphemistically named Ministry of Plenty.

Other literary portrayals of planned economies include Yevgeny Zamyatin's We (1924), which influenced Orwell's work. Like Nineteen Eighty-Four, Ayn Rand's dystopian 1938 story Anthem offered an artistic portrayal of a command economy that was influenced by We. The difference is that it was a primitivist planned economy as opposed to the advanced technology of We or Brave New World.

Central planning

Advantages

The government can harness land, labor, and capital to serve the economic objectives of the state. Consumer demand can be restrained in favor of greater capital investment for economic development in a desired pattern. In international comparisons, state-socialist nations have compared favorably with capitalist nations in health indicators such as infant mortality and life expectancy. However, according to Michael Ellman, the reality of this, at least regarding infant mortality, varies depending on whether official Soviet or WHO definitions are used.

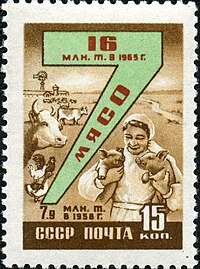

The state can begin building massive heavy industries at once in an underdeveloped economy without waiting years for capital to accumulate through the expansion of light industry and without reliance on external financing. This is what happened in the Soviet Union during the 1930s when the government forced the share of gross national income dedicated to private consumption down from 80% to 50%. As a result of this development, the Soviet Union experienced massive growth in heavy industry, with a concurrent massive contraction of its agricultural sector due to the labor shortage.

Disadvantages

Economic instability

Studies of command economies of the Eastern Bloc in the 1950s and 1960s by both American and Eastern European economists found that contrary to the expectations of both groups they showed greater fluctuations in output than market economies during the same period.

Inefficient resource distribution

Critics of planned economies argue that planners cannot detect consumer preferences, shortages and surpluses with sufficient accuracy and therefore cannot efficiently co-ordinate production (in a market economy, a free price system is intended to serve this purpose). This difficulty was notably written about by economists Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek, who referred to subtly distinct aspects of the problem as the economic calculation problem and local knowledge problem, respectively. These distinct aspects were also present in the economic thought of Michael Polanyi.

Whereas the former stressed the theoretical underpinnings of a market economy to subjective value theory while attacking the labor theory of value, the latter argued that the only way to satisfy individuals who have a constantly changing hierarchy of needs and are the only ones to possess their particular individual's circumstances is by allowing those with the most knowledge of their needs to have it in their power to use their resources in a competing marketplace to meet the needs of the most consumers most efficiently. This phenomenon is recognized as spontaneous order. Additionally, misallocation of resources would naturally ensue by redirecting capital away from individuals with direct knowledge and circumventing it into markets where a coercive monopoly influences behavior, ignoring market signals. According to Tibor Machan, "[w]ithout a market in which allocations can be made in obedience to the law of supply and demand, it is difficult or impossible to funnel resources with respect to actual human preferences and goals".

Historian Robert Vincent Daniels regarded the Stalinist period to represent an abrupt break with Lenin's government in terms of economic planning in which an deliberated, scientific system of planning that featured former Menshevik economists at Gosplan had been replaced with a hasty version of planning with unrealistic targets, bureaucratic waste, bottlenecks and shortages. Stalin's formulations of national plans in terms of physical quantity of output was also attributed by Daniels as a source for the stagnant levels of efficiency and quality.

Suppression of economic democracy and self-management

Economist Robin Hahnel, who supports participatory economics, a form of socialist decentralized planned economy, notes that even if central planning overcame its inherent inhibitions of incentives and innovation, it would nevertheless be unable to maximize economic democracy and self-management, which he believes are concepts that are more intellectually coherent, consistent and just than mainstream notions of economic freedom. Furthermore, Hahnel states:

Combined with a more democratic political system, and redone to closer approximate a best case version, centrally planned economies no doubt would have performed better. But they could never have delivered economic self-management, they would always have been slow to innovate as apathy and frustration took their inevitable toll, and they would always have been susceptible to growing inequities and inefficiencies as the effects of differential economic power grew. Under central planning neither planners, managers, nor workers had incentives to promote the social economic interest. Nor did impeding markets for final goods to the planning system enfranchise consumers in meaningful ways. But central planning would have been incompatible with economic democracy even if it had overcome its information and incentive liabilities. And the truth is that it survived as long as it did only because it was propped up by unprecedented totalitarian political power.

Command economy

Planned economies contrast with command economies in that a planned economy is "an economic system in which the government controls and regulates production, distribution, prices, etc." whereas a command economy necessarily has substantial public ownership of industry while also having this type of regulation. In command economies, important allocation decisions are made by government authorities and are imposed by law.

This is contested by some Marxists. Decentralized planning has been proposed as a basis for socialism and has been variously advocated by anarchists, council communists, libertarian Marxists and other democratic and libertarian socialists who advocate a non-market form of socialism, in total rejection of the type of planning adopted in the economy of the Soviet Union.

Most of a command economy is organized in a top-down administrative model by a central authority, where decisions regarding investment and production output requirements are decided upon at the top in the chain of command, with little input from lower levels. Advocates of economic planning have sometimes been staunch critics of these command economies. Leon Trotsky believed that those at the top of the chain of command, regardless of their intellectual capacity, operated without the input and participation of the millions of people who participate in the economy and who understand/respond to local conditions and changes in the economy. Therefore, they would be unable to effectively coordinate all economic activity.

Historians have associated planned economies with Marxist–Leninist states and the Soviet economic model. Since the 1980s, it has been contested that the Soviet economic model did not actually constitute a planned economy in that a comprehensive and binding plan did not guide production and investment. The further distinction of an administrative-command system emerged as a new designation in some academic circles for the economic system that existed in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc, highlighting the role of centralized hierarchical decision-making in the absence of popular control over the economy. The possibility of a digital planned economy was explored in Chile between 1971 and 1973 with the development of Project Cybersyn and by Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Kharkevich, head of the Department of Technical Physics in Kiev in 1962.

While both economic planning and a planned economy can be either authoritarian or democratic and participatory, democratic socialist critics argue that command economies under modern-day communism is highly undemocratic and totalitarian in practice. Indicative planning is a form of economic planning in market economies that directs the economy through incentive-based methods. Economic planning can be practiced in a decentralized manner through different government authorities. In some predominantly market-oriented and Western mixed economies, the state utilizes economic planning in strategic industries such as the aerospace industry. Mixed economies usually employ macroeconomic planning while micro-economic affairs are left to the market and price system.

Decentralized planning

A decentralized-planned economy, occasionally called horizontally planned economy due to its horizontalism, is a type of planned economy in which the investment and allocation of consumer and capital goods is explicated accordingly to an economy-wide plan built and operatively coordinated through a distributed network of disparate economic agents or even production units itself. Decentralized planning is usually held in contrast to centralized planning, in particular the Soviet-type economic planning of the Soviet Union's command economy, where economic information is aggregated and used to formulate a plan for production, investment and resource allocation by a single central authority. Decentralized planning can take shape both in the context of a mixed economy as well as in a post-capitalist economic system. This form of economic planning implies some process of democratic and participatory decision-making within the economy and within firms itself in the form of industrial democracy. Computer-based forms of democratic economic planning and coordination between economic enterprises have also been proposed by various computer scientists and radical economists. Proponents present decentralized and participatory economic planning as an alternative to market socialism for a post-capitalist society.

Decentralized planning has been a feature of anarchist and socialist economics. Variations of decentralized planning such as economic democracy, industrial democracy and participatory economics have been promoted by various political groups, most notably anarchists, democratic socialists, guild socialists, libertarian Marxists, libertarian socialists, revolutionary syndicalists and Trotskyists. During the Spanish Revolution, some areas where anarchist and libertarian socialist influence through the CNT and UGT was extensive, particularly rural regions, were run on the basis of decentralized planning resembling the principles laid out by anarcho-syndicalist Diego Abad de Santillan in the book After the Revolution. Trotsky had urged economic decentralisation between the state, oblast regions and factories during the NEP period to counter structural inefficiency and the problem of bureaucracy.

Models

Negotiated coordination

Economist Pat Devine has created a model of decentralized economic planning called "negotiated coordination" which is based upon social ownership of the means of production by those affected by the use of the assets involved, with the allocation of consumer and capital goods made through a participatory form of decision-making by those at the most localized level of production. Moreover, organizations that utilize modularity in their production processes may distribute problem solving and decision making.

Participatory planning

The planning structure of a decentralized planned economy is generally based on a consumers council and producer council (or jointly, a distributive cooperative) which is sometimes called a consumers' cooperative. Producers and consumers, or their representatives, negotiate the quality and quantity of what is to be produced. This structure is central to guild socialism, participatory economics and the economic theories related to anarchism.

Practice

Kerala

Some decentralized participation in economic planning has been implemented in various regions and states in India, most notably in Kerala. Local level planning agencies assess the needs of people who are able to give their direct input through the Gram Sabhas (village-based institutions) and the planners subsequently seek to plan accordingly.

Revolutionary Catalonia

Some decentralized participation in economic planning has been implemented across Revolutionary Spain, most notably in Catalonia, during the Spanish Revolution of 1936.