Liberal democracy, western-style democracy, or substantive democracy is a form of government that combines the organization of a representative democracy with ideas of liberal political philosophy.

Common elements within a liberal democracy are: elections between or among multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into different branches of government, the rule of law in everyday life as part of an open society, a market economy with private property, universal suffrage, and the equal protection of human rights, civil rights, civil liberties, and political freedoms for all citizens. Substantive democracy refers to substantive rights and substantive laws, which can include substantive equality, the equality of outcome for subgroups in society. Liberal democracy emphasizes the separation of powers, an independent judiciary, and a system of checks and balances between branches of government. Multi-party systems with at least two persistent, viable political parties are characteristic of liberal democracies.

Governmental authority is legitimately exercised only in accordance with written, publicly disclosed laws adopted and enforced in accordance with established procedure. To define the system in practice, liberal democracies often draw upon a constitution, either codified or uncodified, to delineate the powers of government and enshrine the social contract. A liberal democracy may take various and mixed constitutional forms: it may be a constitutional monarchy or a republic. It may have a parliamentary system, presidential system, or semi-presidential system. Liberal democracies are contrasted with illiberal democracies and dictatorships. Some liberal democracies, especially those with large populations, use federalism (also known as vertical separation of powers) in order to prevent abuse and increase public input by dividing governing powers between municipal, provincial and national governments. The characteristics of liberal democracies are correlated with increased political stability, lower corruption, better management of resources, and better health indicators such as life expectancy and infant mortality. Liberal democracy traces its origins—and its name—to the Age of Enlightenment. The conventional views supporting monarchies and aristocracies were challenged at first by a relatively small group of Enlightenment intellectuals, who believed that human affairs should be guided by reason and principles of liberty and equality. They argued that all people are created equal, that governments exist to serve the people—not vice versa—and that laws should apply to those who govern as well as to the governed (a concept known as rule of law), formulated in Europe as Rechtsstaat. Some of these ideas began to be expressed in England in the 17th century. By the late 18th century, leading philosophers such as John Locke had published works that spread around the European continent and beyond. These ideas and beliefs influenced the American Revolution and the French Revolution. After a period of expansion in the second half of the 20th century, liberal democracy became a prevalent political system in the world.

Origins

Liberal democracy traces its origins—and its name—to 18th-century Europe, during the Age of Enlightenment. At the time, the vast majority of European states were monarchies, with political power held either by the monarch or the aristocracy. The possibility of democracy had not been a seriously considered political theory since classical antiquity and the widely held belief was that democracies would be inherently unstable and chaotic in their policies due to the changing whims of the people. It was further believed that democracy was contrary to human nature, as human beings were seen to be inherently evil, violent and in need of a strong leader to restrain their destructive impulses. Many European monarchs held that their power had been ordained by God and that questioning their right to rule was tantamount to blasphemy.

These conventional views were challenged at first by a relatively small group of Enlightenment intellectuals, who believed that human affairs should be guided by reason and principles of liberty and equality. They argued that all people are created equal and therefore political authority cannot be justified on the basis of noble blood, a supposed privileged connection to God or any other characteristic that is alleged to make one person superior to others. They further argued that governments exist to serve the people—not vice versa—and that laws should apply to those who govern as well as to the governed (a concept known as rule of law).

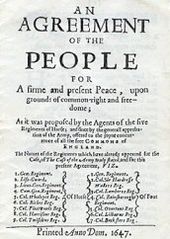

Some of these ideas began to be expressed in England in the 17th century. There was renewed interest in Magna Carta, and passage of the Petition of Right in 1628 and Habeas Corpus Act in 1679 established certain liberties for subjects. The idea of a political party took form with groups debating rights to political representation during the Putney Debates of 1647. After the English Civil Wars (1642–1651) and the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the Bill of Rights was enacted in 1689, which codified certain rights and liberties. The Bill set out the requirement for regular elections, rules for freedom of speech in Parliament and limited the power of the monarch, ensuring that, unlike almost all of Europe at the time, royal absolutism would not prevail. This led to significant social change in Britain in terms of the position of individuals in society and the growing power of Parliament in relation to the monarch.

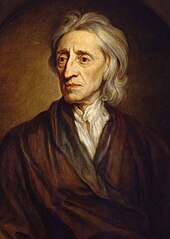

By the late 18th century, leading philosophers of the day had published works that spread around the European continent and beyond. One of the most influential of these philosophers was English empiricist John Locke, who refuted monarchical absolutism in his Two Treatises of Government. According to Locke, individuals entered into a social contract with a state, surrendering some of their liberties in exchange for the protection of their natural rights. Locke advanced that governments were only legitimate if they maintained the consent of the governed and that citizens had the right to instigate a rebellion against their government if that government acted against their interests. These ideas and beliefs influenced the American Revolution and the French Revolution, which gave birth to the philosophy of liberalism and instituted forms of government that attempted to put the principles of the Enlightenment philosophers into practice.

When the first prototypical liberal democracies were founded, the liberals themselves were viewed as an extreme and rather dangerous fringe group that threatened international peace and stability. The conservative monarchists who opposed liberalism and democracy saw themselves as defenders of traditional values and the natural order of things and their criticism of democracy seemed vindicated when Napoleon Bonaparte took control of the young French Republic, reorganized it into the first French Empire and proceeded to conquer most of Europe. Napoleon was eventually defeated and the Holy Alliance was formed in Europe to prevent any further spread of liberalism or democracy. However, liberal democratic ideals soon became widespread among the general population and over the 19th century traditional monarchy was forced on a continuous defensive and withdrawal. The Dominions of the British Empire became laboratories for liberal democracy from the mid 19th century onward. In Canada, responsible government began in the 1840s and in Australia and New Zealand, parliamentary government elected by male suffrage and secret ballot was established from the 1850s and female suffrage achieved from the 1890s.

Reforms and revolutions helped move most European countries towards liberal democracy. Liberalism ceased being a fringe opinion and joined the political mainstream. At the same time, a number of non-liberal ideologies developed that took the concept of liberal democracy and made it their own. The political spectrum changed; traditional monarchy became more and more a fringe view and liberal democracy became more and more mainstream. By the end of the 19th century, liberal democracy was no longer only a liberal idea, but an idea supported by many different ideologies. After World War I and especially after World War II, liberal democracy achieved a dominant position among theories of government and is now endorsed by the vast majority of the political spectrum.

Although liberal democracy was originally put forward by Enlightenment liberals, the relationship between democracy and liberalism has been controversial since the beginning and was problematized in the 20th century. In his book Freedom and Equality in a Liberal Democratic State, Jasper Doomen posited that freedom and equality are necessary for a liberal democracy. In his book The End of History and the Last Man, Francis Fukuyama says that since the French Revolution, liberal democracy has repeatedly proven to be a fundamentally better system (ethically, politically, economically) than any of the alternatives, and that democracy will become more and more prevalent in the long term, although it may suffer temporary setbacks. The research institute Freedom House today simply defines liberal democracy as an electoral democracy also protecting civil liberties.

Rights and freedoms

Political freedom is a central concept in history and political thought and one of the most important features of democratic societies. Political freedom was described as freedom from oppression or coercion, the absence of disabling conditions for an individual and the fulfillment of enabling conditions, or the absence of life conditions of compulsion, e.g. economic compulsion, in a society. Although political freedom is often interpreted negatively as the freedom from unreasonable external constraints on action, it can also refer to the positive exercise of rights, capacities and possibilities for action and the exercise of social or group rights. The concept can also include freedom from internal constraints on political action or speech (e.g. social conformity, consistency, or inauthentic behaviour). The concept of political freedom is closely connected with the concepts of civil liberties and human rights, which in democratic societies are usually afforded legal protection from the state.

Laws in liberal democracies may limit certain freedoms. The common justification for these limits is that they are necessary to guarantee the existence of democracy, or the existence of the freedoms themselves. For example, democratic governments may impose restrictions on free speech, with examples including Holocaust denial and hate speech. Some discriminatory behavior may be prohibited. For example, public accommodations in the United States may not discriminate on the basis of "race, color, religion, or national origin." There are various legal limitations such as copyright and laws against defamation. There may be limits on anti-democratic speech, on attempts to undermine human rights and on the promotion or justification of terrorism. In the United States more than in Europe, during the Cold War such restrictions applied to communists. Now they are more commonly applied to organizations perceived as promoting terrorism or the incitement of group hatred. Examples include anti-terrorism legislation, the shutting down of Hezbollah satellite broadcasts and some laws against hate speech. Critics claim that these limitations may go too far and that there may be no due and fair judicial process. Opinion is divided on how far democracy can extend to include the enemies of democracy in the democratic process. If relatively small numbers of people are excluded from such freedoms for these reasons, a country may still be seen as a liberal democracy. Some argue that this is only quantitatively (not qualitatively) different from autocracies that persecute opponents, since only a small number of people are affected and the restrictions are less severe, but others emphasize that democracies are different. At least in theory, opponents of democracy are also allowed due process under the rule of law.

Since it is possible to disagree over which rights are considered fundamental, different countries may treat particular rights in different ways. For example:

- The constitutions of Canada, India, Israel, Mexico and the United States guarantee freedom from double jeopardy, a right not provided in some other legal systems.

- Legal systems that use politically elected court jurors, such as Sweden, view a (partly) politicized court system as a main component of accountable government. Other democracies employ trial by jury with the intent of shielding against the influence of politicians over trials.

Liberal democracies usually have universal suffrage, granting all adult citizens the right to vote regardless of ethnicity, sex, property ownership, race, age, sexuality, gender, income, social status, or religion. However, historically some countries regarded as liberal democracies have had a more limited franchise. Even today, some countries, considered to be liberal democracies, do not have truly universal suffrage. In some countries, members of political organizations with connections to historical totalitarian governments (for example formerly predominant communist, fascist or Nazi governments in some European countries) may be deprived of the vote and the privilege of holding certain jobs. In the United Kingdom people serving long prison sentences are unable to vote, a policy which has been ruled a human rights violation by the European Court of Human Rights. A similar policy is also enacted in most of the United States. According to a study by Coppedge and Reinicke, at least 85% of democracies provided for universal suffrage. Many nations require positive identification before allowing people to vote. For example, in the United States two thirds of the states require their citizens to provide identification to vote, which also provide state IDs for free. The decisions made through elections are made by those who are members of the electorate and who choose to participate by voting.

In 1971, Robert Dahl summarized the fundamental rights and freedoms shared by all liberal democracies as eight rights:

- Freedom to form and join organizations.

- Freedom of expression.

- Right to vote.

- Right to run for public office.

- Right of political leaders to compete for support and votes.

- Freedom of alternative sources of information

- Free and fair elections.

- Right to control government policy through votes and other expressions of preference.

Preconditions

For a political regime to be considered a liberal democracy it must contain in its governing over a nation-state the provision of civil rights- the non-discrimination in the provision of public goods such as justice, security, education and health- in addition to, political rights- the guarantee of free and fair electoral contests, which allow the winners of such contests to determine policy subject to the constraints established by other rights, when these are provided- and property rights- which protect asset holders and investors against expropriation by the state or other groups. In this way, liberal democracy is set apart from electoral democracy, as free and fair elections – the hallmark of electoral democracy – can be separated from equal treatment and non-discrimination – the hallmarks of liberal democracy. In liberal democracy, an elected government cannot discriminate against specific individuals or groups when it administers justice, protects basic rights such as freedom of assembly and free speech, provides for collective security, or distributes economic and social benefits. According to Seymour Martin Lipset, although they are not part of the system of government as such, a modicum of individual and economic freedoms, which result in the formation of a significant middle class and a broad and flourishing civil society, are seen as pre-conditions for liberal democracy.

For countries without a strong tradition of democratic majority rule, the introduction of free elections alone has rarely been sufficient to achieve a transition from dictatorship to democracy; a wider shift in the political culture and gradual formation of the institutions of democratic government are needed. There are various examples—for instance, in Latin America—of countries that were able to sustain democracy only temporarily or in a limited fashion until wider cultural changes established the conditions under which democracy could flourish.

One of the key aspects of democratic culture is the concept of a loyal opposition, where political competitors may disagree, but they must tolerate one another and acknowledge the legitimate and important roles that each play. This is an especially difficult cultural shift to achieve in nations where transitions of power have historically taken place through violence. The term means in essence that all sides in a democracy share a common commitment to its basic values. The ground rules of the society must encourage tolerance and civility in public debate. In such a society, the losers accept the judgement of the voters when the election is over and allow for the peaceful transfer of power. According to Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira, this is tied to another key concept of democratic cultures, the protection of minorities, where the losers are safe in the knowledge that they will neither lose their lives nor their liberty and will continue to participate in public life. They are loyal not to the specific policies of the government, but to the fundamental legitimacy of the state and to the democratic process itself.

One requirement of liberal democracy is political equality amongst voters (ensuring that all voices and all votes count equally) and that these can properly influence government policy, requiring quality procedure and quality content of debate that provides an accountable result, this may apply within elections or to procedures between elections. This requires universal, adult suffrage; recurring, free elections, competitive and fair elections; multiple political parties and a wide variety of information so that citizens can rationally and effectively put pressure onto the government, including that it can be checked, evaluated and removed. This can include or lead to accountability, responsiveness to the desires of citizens, the rule of law, full respect of rights and implementation of political, social and economic freedom. Other liberal democracies consider the requirement of minority rights and preventing tyranny of the majority. One of the most common ways is by actively preventing discrimination by the government (bill of rights) but can also include requiring concurrent majorities in several constituencies (confederalism); guaranteeing regional government (federalism); broad coalition governments (consociationalism) or negotiating with other political actors, such as pressure groups (neocorporatism). These split political power amongst many competing and cooperating actors and institutions by requiring the government to respect minority groups and give them their positive freedoms, negotiate across multiple geographical areas, become more centrist among cooperative parties and open up with new social groups.

In a new study published in Nature Human Behaviour, Damian J. Ruck and his co-authors take a major step toward resolving this long-standing and seemingly irresolvable debate about whether culture shapes regimes or regimes shape culture. This study resolves the debate in favor of culture's causal primacy and shows that it is the civic and emancipative values (liberty, impartiality and contractarianism) among a country's citizens that give rise to democratic institutions, not vice versa.

Liberal democracies around the world

Several organizations and political scientists maintain lists of free and unfree states, both in the present and going back a couple centuries. Of these, the best known may be the Polity Data Set and that produced by Freedom House and Larry Diamond.

There is agreement amongst several intellectuals and organizations such as Freedom House that the states of the European Union (with the exception of Poland and Hungary), United Kingdom, Norway, Iceland, Switzerland, Japan, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, South Korea, Taiwan, the United States, India, Canada, Uruguay, Costa Rica, Israel, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand are liberal democracies. Liberal democracies are susceptible to democratic backsliding and this is taking place or has taken place in several countries, including, but not limited to, the United States, Poland, Hungary, and Israel.

Freedom House considers many of the officially democratic governments in Africa and the former Soviet Union to be undemocratic in practice, usually because the sitting government has a strong influence over election outcomes. Many of these countries are in a state of considerable flux.

Officially non-democratic forms of government, such as single-party states and dictatorships, are more common in East Asia, the Middle East and North Africa.

The 2019 Freedom in the World report noted a fall in the number of countries with liberal democracies over the 13 years from 2005 to 2018, citing declines in 'political rights and civil liberties'. The 2020 and 2021 reports document further reductions in the number of free countries in the world.

Types

Proportional vs. plurality representation

Plurality voting system award seats according to regional majorities. The political party or individual candidate who receives the most votes, wins the seat which represents that locality. There are other democratic electoral systems, such as the various forms of proportional representation, which award seats according to the proportion of individual votes that a party receives nationwide or in a particular region.

One of the main points of contention between these two systems is whether to have representatives who are able to effectively represent specific regions in a country, or to have all citizens' vote count the same, regardless of where in the country they happen to live.

Some countries, such as Germany and New Zealand, address the conflict between these two forms of representation by having two categories of seats in the lower house of their national legislative bodies. The first category of seats is appointed according to regional popularity and the remainder are awarded to give the parties a proportion of seats that is equal—or as equal as practicable—to their proportion of nationwide votes. This system is commonly called mixed member proportional representation.

The Australian Government incorporates both systems in having the preferential voting system applicable to the lower house and proportional representation by state in the upper house. This system is argued to result in a more stable government, while having a better diversity of parties to review its actions. The various state and territory governments in Australia employ a range of a different electoral systems.

Presidential vs. parliamentary systems

A presidential system is a system of government of a republic in which the executive branch is elected separately from the legislative. A parliamentary system is distinguished by the executive branch of government being dependent on the direct or indirect support of the parliament, often expressed through a vote of confidence.

The presidential system of democratic government has been adopted in Latin America, Africa and parts of the former Soviet Union, largely by the example of the United States. Constitutional monarchies (dominated by elected parliaments) are present in Northern Europe and some former colonies which peacefully separated, such as Australia and Canada. Others have also arisen in Spain, East Asia and a variety of small nations around the world. Former British territories such as South Africa, India, Ireland and the United States opted for different forms at the time of independence. The parliamentary system is widely used in the European Union and neighbouring countries.

Impact on economic growth

Recent academic studies have found that democratisation is beneficial for national growth. However, the effect of democratisation has not been studied as yet. The most common factors that determine whether a country's economy grows or not are the country's level of development and the educational level of its newly elected democratic leaders. As a result, there is no clear indication of how to determine which factors contribute to economic growth in a democratic country.

However, there is disagreement regarding how much credit the democratic system can take for this growth. One observation is that democracy became widespread only after the Industrial Revolution and the introduction of capitalism. On the other hand, the Industrial Revolution started in England which was one of the most democratic nations for its time within its own borders, but this democracy was very limited and did not apply to the colonies which contributed significantly to the wealth.

Several statistical studies support the theory that a higher degree of economic freedom, as measured with one of the several Indices of Economic Freedom which have been used in numerous studies, increases economic growth and that this in turn increases general prosperity, reduces poverty and causes democratisation. This is a statistical tendency and there are individual exceptions like Mali, which is ranked as "Free" by Freedom House, but is a Least Developed Country, or Qatar, which has arguably the highest GDP per capita in the world, but has never been democratic. There are also other studies suggesting that more democracy increases economic freedom, although a few find no or even a small negative effect.

Some argue that economic growth due to its empowerment of citizens will ensure a transition to democracy in countries such as Cuba. However, other dispute this and even if economic growth has caused democratisation in the past, it may not do so in the future. Dictators may now have learned how to have economic growth without this causing more political freedom.

A high degree of oil or mineral exports is strongly associated with nondemocratic rule. This effect applies worldwide and not only to the Middle East. Dictators who have this form of wealth can spend more on their security apparatus and provide benefits which lessen public unrest. Also, such wealth is not followed by the social and cultural changes that may transform societies with ordinary economic growth.

A 2006 meta-analysis found that democracy has no direct effect on economic growth. However, it has strong and significant indirect effects which contribute to growth. Democracy is associated with higher human capital accumulation, lower inflation, lower political instability and higher economic freedom. There is also some evidence that it is associated with larger governments and more restrictions on international trade.

If leaving out East Asia, then during the last forty-five years poor democracies have grown their economies 50% more rapidly than nondemocracies. Poor democracies such as the Baltic countries, Botswana, Costa Rica, Ghana and Senegal have grown more rapidly than nondemocracies such as Angola, Syria, Uzbekistan and Zimbabwe.

Of the eighty worst financial catastrophes during the last four decades, only five were in democracies. Similarly, poor democracies are half likely as non-democracies to experience a 10 per cent decline in GDP per capita over the course of a single year.

Justifications and support

Increased political stability

Several key features of liberal democracies are associated with political stability, including economic growth, as well as robust state institutions that guarantee free elections, the rule of law, and individual liberties.

One argument for democracy is that by creating a system where the public can remove administrations, without changing the legal basis for government, democracy aims at reducing political uncertainty and instability and assuring citizens that however much they may disagree with present policies, they will be given a regular chance to change those who are in power, or change policies with which they disagree. This is preferable to a system where political change takes place through violence.

One notable feature of liberal democracies is that their opponents (those groups who wish to abolish liberal democracy) rarely win elections. Advocates use this as an argument to support their view that liberal democracy is inherently stable and can usually only be overthrown by external force, while opponents argue that the system is inherently stacked against them despite its claims to impartiality. In the past, it was feared that democracy could be easily exploited by leaders with dictatorial aspirations, who could get themselves elected into power. However, the actual number of liberal democracies that have elected dictators into power is low. When it has occurred, it is usually after a major crisis has caused many people to doubt the system or in young/poorly functioning democracies. Some possible examples include Adolf Hitler during the Great Depression and Napoleon III, who became first President of the Second French Republic and later Emperor.

Effective response in wartime

By definition, a liberal democracy implies that power is not concentrated. One criticism is that this could be a disadvantage for a state in wartime, when a fast and unified response is necessary. The legislature usually must give consent before the start of an offensive military operation, although sometimes the executive can do this on its own while keeping the legislature informed. If the democracy is attacked, then no consent is usually required for defensive operations. The people may vote against a conscription army.

However, actual research shows that democracies are more likely to win wars than non-democracies. One explanation attributes this primarily to "the transparency of the polities, and the stability of their preferences, once determined, democracies are better able to cooperate with their partners in the conduct of wars". Other research attributes this to superior mobilisation of resources or selection of wars that the democratic states have a high chance of winning.

Stam and Reiter also note that the emphasis on individuality within democratic societies means that their soldiers fight with greater initiative and superior leadership. Officers in dictatorships are often selected for political loyalty rather than military ability. They may be exclusively selected from a small class or religious/ethnic group that support the regime. The leaders in nondemocracies may respond violently to any perceived criticisms or disobedience. This may make the soldiers and officers afraid to raise any objections or do anything without explicit authorisation. The lack of initiative may be particularly detrimental in modern warfare. Enemy soldiers may more easily surrender to democracies since they can expect comparatively good treatment. In contrast, Nazi Germany killed almost 2/3 of the captured Soviet soldiers and 38% of the American soldiers captured by North Korea in the Korean War were killed.

Better information on and corrections of problems

A democratic system may provide better information for policy decisions. Undesirable information may more easily be ignored in dictatorships, even if this undesirable or contrarian information provides early warning of problems. Anders Chydenius put forward the argument for freedom of the press for this reason in 1776. The democratic system also provides a way to replace inefficient leaders and policies, thus problems may continue longer and crises of all kinds may be more common in autocracies.

Reduction of corruption

Research by the World Bank suggests that political institutions are extremely important in determining the prevalence of corruption: (long term) democracy, parliamentary systems, political stability and freedom of the press are all associated with lower corruption. Freedom of information legislation is important for accountability and transparency. The Indian Right to Information Act "has already engendered mass movements in the country that is bringing the lethargic, often corrupt bureaucracy to its knees and changing power equations completely".

Better use of resources

Democracies can put in place better education, longer life expectancy, lower infant mortality, access to drinking water and better health care than dictatorships. This is not due to higher levels of foreign assistance or spending a larger percentage of GDP on health and education, as instead the available resources are managed better.

Prominent economist Amartya Sen has noted that no functioning democracy has ever suffered a large scale famine. Refugee crises almost always occur in non-democracies. From 1985 to 2008, the eighty-seven largest refugee crises occurred in autocracies.

Health and human development

Democracy correlates with a higher score on the Human Development Index and a lower score on the human poverty index.

Several health indicators (life expectancy and infant and maternal mortality) have a stronger and more significant association with democracy than they have with GDP per capita, rise of the public sector or income inequality.

In the post-communist nations, after an initial decline those that are the most democratic have achieved the greatest gains in life expectancy.

Democratic peace theory

Numerous studies using many different kinds of data, definitions and statistical analyses have found support for the democratic peace theory. The original finding was that liberal democracies have never made war with one another. More recent research has extended the theory and finds that democracies have few militarized interstate disputes causing less than 1,000 battle deaths with one another, that those militarized interstate disputes that have occurred between democracies have caused few deaths and that democracies have few civil wars. There are various criticisms of the theory, including at least as many refutations as alleged proofs of the theory, some 200 deviant cases, failure to treat democracy as a multidimensional concept and that correlation is not causation.

Minimization of political violence

Rudolph Rummel's Power Kills says that liberal democracy, among all types of regimes, minimizes political violence and is a method of nonviolence. Rummel attributes this firstly to democracy instilling an attitude of tolerance of differences, an acceptance of losing and a positive outlook towards conciliation and compromise.

A study published by the British Academy, on Violence and Democracy, argues that in practice, liberal democracy has not stopped those running the state from exerting acts of violence both within and outside their borders. The paper also argues that police killings, profiling of racial and religious minorities, online surveillance, data collection, or media censorship are a couple of ways in which successful states maintain a monopoly on violence.

Objections and criticism

Campaign costs

In Athenian democracy, some public offices were randomly allocated to citizens, in order to inhibit the effects of plutocracy. Aristotle described the law courts in Athens which were selected by lot as democratic and described elections as oligarchic.

Political campaigning in representative democracies can favor the rich due to campaign costs, a form of plutocracy where only a very small number of wealthy individuals can actually affect government policy in their favor and toward plutonomy. Stringent campaign finance laws can correct this perceived problem.

Other studies predicted that the global trend toward plutonomies would continue, for various reasons, including "capitalist-friendly governments and tax regimes". However, they also say that, since "political enfranchisement remains as was—one person, one vote, at some point it is likely that labor will fight back against the rising profit share of the rich and there will be a political backlash against the rising wealth of the rich."

Economist Steven Levitt says in his book Freakonomics that campaign spending is no guarantee of electoral success. He compared electoral success of the same pair of candidates running against one another repeatedly for the same job, as often happens in United States congressional elections, where spending levels varied. He concludes:

- A winning candidate can cut his spending in half and lose only 1 percent of the vote. Meanwhile, a losing candidate who doubles his spending can expect to shift the vote in his favor by only that same 1 percent.

On September 18, 2014, Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page's study concluded "Multivariate analysis indicates that economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence. The results provide substantial support for theories of Economic-Elite Domination and for theories of Biased Pluralism, but not for theories of Majoritarian Electoral Democracy or Majoritarian Pluralism."

Media

Critics of the role of the media in liberal democracies allege that concentration of media ownership leads to major distortions of democratic processes. In Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky argue via their Propaganda Model that the corporate media limits the availability of contesting views and assert this creates a narrow spectrum of elite opinion. This is a natural consequence, they say, of the close ties between powerful corporations and the media and thus limited and restricted to the explicit views of those who can afford it. Furthermore, the media's negative influence can be seen in social media where vast numbers of individuals seek their political information which is not always correct and may be controlled. For example, as of 2017, two-thirds (67%) of Americans report that they get at least some of their news from social media, as well as a rising number of countries are exercising extreme control over the flow of information. This may contribute to large numbers of individuals using social media platforms but not always gaining correct political information. This may cause conflict with liberal democracy and some of its core principles, such as freedom, if individuals are not entirely free since their governments are seizing that level of control on media sites. The notion that the media is used to indoctrinate the public is also shared by Yascha Mounk's The People Vs Democracy which states that the government benefits from the public having a relatively similar worldview and that this one-minded ideal is one of the principles in which Liberal Democracy stands.

Defenders responding to such arguments say that constitutionally protected freedom of speech makes it possible for both for-profit and non-profit organisations to debate the issues. They argue that media coverage in democracies simply reflects public preferences and does not entail censorship. Especially with new forms of media such as the Internet, it is not expensive to reach a wide audience, if an interest in the ideas presented exists.

Limited voter turnout

Low voter turnout, whether the cause is disenchantment, indifference or contentment with the status quo, may be seen as a problem, especially if disproportionate in particular segments of the population. Although turnout levels vary greatly among modern democratic countries and in various types and levels of elections within countries, at some point low turnout may prompt questions as to whether the results reflect the will of the people, whether the causes may be indicative of concerns to the society in question, or in extreme cases the legitimacy of the electoral system.

Get out the vote campaigns, either by governments or private groups, may increase voter turnout, but distinctions must be made between general campaigns to raise the turnout rate and partisan efforts to aid a particular candidate, party or cause. Other alternatives include increased use of absentee ballots, or other measures to ease or improve the ability to vote, including electronic voting.

Several nations have forms of compulsory voting, with various degrees of enforcement. Proponents argue that this increases the legitimacy—and thus also popular acceptance—of the elections and ensures political participation by all those affected by the political process and reduces the costs associated with encouraging voting. Arguments against include restriction of freedom, economic costs of enforcement, increased number of invalid and blank votes and random voting.

Bureaucracy

A persistent libertarian and monarchist critique of democracy is the claim that it encourages the elected representatives to change the law without necessity and in particular to pour forth a flood of new laws, as described in Herbert Spencer's The Man Versus The State. This is seen as pernicious in several ways. New laws constrict the scope of what were previously private liberties. Rapidly changing laws make it difficult for a willing non-specialist to remain law-abiding. This may be an invitation for law-enforcement agencies to misuse power. The claimed continual complication of the law may be contrary to a claimed simple and eternal natural law—although there is no consensus on what this natural law is, even among advocates. Supporters of democracy point to the complex bureaucracy and regulations that has occurred in dictatorships, like many of the former communist states.

The bureaucracy in liberal democracies is often criticised for a claimed slowness and complexity of their decision-making. The term "red tape" is a synonym of slow bureaucratic functioning that hinders quick results in a liberal democracy.

Short-term focus

By definition, modern liberal democracies allow for regular changes of government. That has led to a common criticism of their short-term focus. In four or five years the government will face a new election and it must think of how it will win that election. That would encourage a preference for policies that will bring short term benefits to the electorate (or to self-interested politicians) before the next election, rather than unpopular policy with longer term benefits. This criticism assumes that it is possible to make long term predictions for a society, something Karl Popper has criticised as historicism.

Besides the regular review of governing entities, short-term focus in a democracy could also be the result of collective short-term thinking. For example, consider a campaign for policies aimed at reducing environmental damage while causing temporary increase in unemployment. However, this risk applies also to other political systems.

Majoritarianism

The tyranny of the majority is the fear that a direct democratic government, reflecting the majority view, can take action that oppresses a particular minority. For instance, a minority holding wealth, property ownership or power (see Federalist No. 10), or a minority of a certain racial and ethnic origin, class or nationality. Theoretically, the majority is a majority of all citizens. If citizens are not compelled by law to vote, it is usually a majority of those who choose to vote. If such of group constitutes a minority, then it is possible that a minority could in theory oppress another minority in the name of the majority. However, such an argument could apply to both direct democracy or representative democracy. Several de facto dictatorships also have compulsory, but not "free and fair" voting in order to try to increase the legitimacy of the regime, such as North Korea.

In her book World on Fire, Yale Law School professor Amy Chua posits that "when free market democracy is pursued in the presence of a market-dominant minority, the almost invariable result is backlash. This backlash typically takes one of three forms. The first is a backlash against markets, targeting the market-dominant minority's wealth. The second is a backlash against democracy by forces favorable to the market-dominant minority. The third is violence, sometimes genocidal, directed against the market-dominant minority itself".

Cases that have been cited as examples of a minority being oppressed by or in the name of the majority include the practice of conscription and laws against homosexuality, pornography, and recreational drug use. Homosexual acts were widely criminalised in democracies until several decades ago and in some democracies like Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, Tunisia, Nigeria, and Malaysia, they still are, reflecting the religious or sexual mores of the majority. The Athenian democracy and the early United States practiced slavery, and even proponents of liberal democracy in the 17th and 18th century were often pro-slavery, which is contradictory of a liberal democracy. Another often quoted example of the "tyranny of the majority" is that Adolf Hitler came to power by "legitimate" democratic procedures. The Nazi Party gained the largest share of votes in the democratic Weimar Republic in 1933. However, his regime's large-scale human rights violations took place after the democratic system had been abolished. Furthermore, the Weimar Constitution in an "emergency" allowed dictatorial powers and suspension of the essentials of the constitution itself without any vote or election.

Proponents of democracy make a number of defenses concerning "tyranny of the majority". One is to argue that the presence of a constitution protecting the rights of all citizens in many democratic countries acts as a safeguard. Generally, changes in these constitutions require the agreement of a supermajority of the elected representatives, or require a judge and jury to agree that evidentiary and procedural standards have been fulfilled by the state, or two different votes by the representatives separated by an election, or sometimes a referendum. These requirements are often combined. The separation of powers into legislative branch, executive branch and judicial branch also makes it more difficult for a small majority to impose their will. This means a majority can still legitimately coerce a minority (which is still ethically questionable), but such a minority would be very small and as a practical matter it is harder to get a larger proportion of the people to agree to such actions.

Another argument is that majorities and minorities can take a markedly different shape on different issues. People often agree with the majority view on some issues and agree with a minority view on other issues. One's view may also change, thus the members of a majority may limit oppression of a minority since they may well in the future themselves be in a minority.

A third common argument is that despite the risks majority rule is preferable to other systems and the tyranny of the majority is in any case an improvement on a tyranny of a minority. All the possible problems mentioned above can also occur in non-democracies with the added problem that a minority can oppress the majority. Proponents of democracy argue that empirical statistical evidence strongly shows that more democracy leads to less internal violence and mass murder by the government. This is sometimes formulated as Rummel's Law, which states that the less democratic freedom a people have, the more likely their rulers are to murder them.

Marxist criticism

Marxists and communists, as well as some non-Marxist socialists and anarchists, argue that liberal democracy under capitalism is constitutively class-based and therefore can never be democratic or participatory. They refer to it as "bourgeois democracy" because they say that ultimately, politicians fight mainly for the interests of the bourgeoisie. As such, liberal democracy is said to represent "the rule of capital".

According to Karl Marx, representation of the interests of different classes is proportional to the influence which a particular class can purchase (through bribes, transmission of propaganda through mass media, economic blackmail, donations for political parties and their campaigns and so on). Thus, the public interest in so-called liberal democracies is systematically corrupted by the wealth of those classes rich enough to gain the appearance of representation. Because of this, he said that multi-party democracies under capitalism are always distorted and anti-democratic, their operation merely furthering the class interests of the owners of the means of production, and the bourgeois class becomes wealthy through a drive to appropriate the surplus-value of the creative labours of the working class. This drive obliges the bourgeois class to amass ever-larger fortunes by increasing the proportion of surplus-value by exploiting the working class through capping workers' terms and conditions as close to poverty levels as possible. Incidentally, this obligation demonstrates the clear limit to bourgeois freedom even for the bourgeoisie itself. According to Marx, parliamentary elections are no more than a cynical, systemic attempt to deceive the people by permitting them, every now and again, to endorse one or other of the bourgeoisie's predetermined choices of which political party can best advocate the interests of capital. Once elected, he said that this parliament, as a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, enacts regulations that actively support the interests of its true constituency, the bourgeoisie (such as bailing out Wall St investment banks; direct socialisation/subsidisation of business—GMH, US/European agricultural subsidies; and even wars to guarantee trade in commodities such as oil).

Vladimir Lenin once argued that liberal democracy had simply been used to give an illusion of democracy whilst maintaining the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, giving as an example the United States's representative democracy which he said consisted of "spectacular and meaningless duels between two bourgeois parties" led by "multimillionaires".

Socialist and communist criticism

Some socialists, such as The Left party in Germany, say that liberal democracy is a dishonest farce used to keep the masses from realizing that their will is irrelevant in the political process. The Chinese Communist Party political concept of whole-process people's democracy criticizes liberal democracy for excessively relying on procedural formalities without genuinely reflecting the interests of the people. Under this primarily consequentialist concept, the most important criteria for a democracy is whether it can "solve the people's real problems", while a system in which "the people are awakened only for voting" is not truly democratic. For example, the Chinese government's 2021 white paper China: Democracy that Works criticizes liberal democracy's shortcoming based on principles of whole process people's democracy.

Vulnerabilities

Authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is perceived by many to be a direct threat to the liberalised democracy practised in many countries. According to American political sociologist and authors Larry Diamond, Marc F. Plattner and Christopher Walker, undemocratic regimes are becoming more assertive. They suggest that liberal democracies introduce more authoritarian measures to counter authoritarianism itself and cite monitoring elections and more control on media in an effort to stop the agenda of undemocratic views. Diamond, Plattner and Walker uses an example of China using aggressive foreign policy against western countries to suggest that a country's society can force another country to behave in a more authoritarian manner. In their book 'Authoritarianism Goes Global: The Challenge to Democracy' they claim that Beijing confronts the United States by building its navy and missile force and promotes the creation of global institutions designed to exclude American and European influence; as such authoritarian states pose a threat to liberal democracy as they seek to remake the world in their own image.

Various authors have also analysed the authoritarian means that are used by liberal democracies to defend economic liberalism and the power of political elites.

War

There are ongoing debates surrounding the effect that war may have on liberal democracy, and whether it cultivates or inhibits democratization.

War may cultivate democratization by "mobilizing the masses, and creating incentives for the state to bargain with the people it needs to contribute to the war effort". An example of this may be seen in the extension of suffrage in the UK after World War I.

War may however inhibit democratization by "providing an excuse for the curtailment of liberties".

Terrorism

Several studies have concluded that terrorism is most common in nations with intermediate political freedom, meaning countries transitioning from autocratic governance to democracy. Nations with strong autocratic governments and governments that allow for more political freedom experience less terrorism.

Populism

There is no one agreed upon definition of populism, with a broader definition settled upon following a conference at the London School of Economics in 1967. Academically, the term "populism" faces criticism that it should be abandoned as a descriptor due to its vagueness. It is typically not fundamentally undemocratic, but it is often anti-liberal. Many will agree on certain features that characterize populism and populists: a conflict between 'the people' and 'the elites', with populists siding with 'the people' and strong disdain for opposition and negative media using labels such as 'fake news'.

Populism is a form of majoritarianism, threatening some of the core principles of liberal democracy such as the rights of the individual. Examples of these can vary from freedom of movement via control on immigration, or opposition to liberal social values such as gay marriage. Populists do this by appealing to the feelings and emotions of the people whilst offering solutions - often vastly simplified - to complex problems.

Populism is a particular threat to the liberal democracy because it exploits the weaknesses of the liberal democratic system. A key weakness of liberal democracies highlighted in 'How Democracies Die', is the conundrum that suppressing populist movements or parties can be seen to be illiberal. Another reason that populism is a threat to liberal democracy is because it exploits the inherent differences between 'Democracy' and 'Liberalism'. For liberal democracy to be effective, a degree of compromise is required as protecting the rights of the individual take precedence if they are threatened by the will of the majority, more commonly known as a tyranny of the majority. Majoritarianism is so ingrained in populism that this core value of a liberal democracy is under threat. This therefore brings into question how effectively liberal democracy can defend itself from populism.

According to Takis Papas in his work Populism and Liberal Democracy: A Comparative and Theoretical Analysis, "democracy has two opposites, one liberal, the other populist". Whereas liberalism accepts a notion of society composed of multiple divisions, populism only acknowledges a society of 'the people' versus 'the elites'. The fundamental beliefs of the populist voter consist of: the belief that oneself is powerless and is a victim of the powerful; a "sense of enmity" rooted in "moral indignation and resentfulness"; and a "longing for future redemption" through the actions of a charismatic leader. Papas says this mindset results in a feeling of victimhood caused by the belief that the society is "made up of victims and perpetrators". Other characteristic of a populist voter is that they are "distinctively irrational" because of the "disproportionate role of emotions and morality" when making a political decision like voting. Moreover, through self-deception they are "wilfully ignorant". In addition, they are "intuitively… and unsettlingly principled" rather than a more "pragmatic" liberal voter.

An example of a populist movement is the 2016 Brexit campaign. The role of the 'elite' in this circumstance was played by the EU and 'London-centric liberals', while the Brexit campaign appealed to workers in industries such as agriculture who were allegedly worse off due to EU membership. This case study also illustrates the potential threat populism can pose to a liberal democracy with the movement heavily relying on disdain for the media. This was done by labeling criticism of Brexit as 'Project Fear'.