Stereotype threat is a situational predicament in which people are or feel themselves to be at risk of conforming to stereotypes about their social group. It is theorized to be a contributing factor to long-standing racial and gender gaps in academic performance. Since its introduction into the academic literature, stereotype threat has become one of the most widely studied topics in the field of social psychology.

Situational factors that increase stereotype threat can include the difficulty of the task, the belief that the task measures their abilities, and the relevance of the stereotype to the task. Individuals show higher degrees of stereotype threat on tasks they wish to perform well on and when they identify strongly with the stereotyped group. These effects are also increased when they expect discrimination due to their identification with a negatively stereotyped group. Repeated experiences of stereotype threat can lead to a vicious circle of diminished confidence, poor performance, and loss of interest in the relevant area of achievement. Stereotype threat has been argued to show a reduction in the performance of individuals who belong to negatively stereotyped groups. Its role in affecting public health disparities has also been suggested.

According to the theory, if negative stereotypes are present regarding a specific group, group members are likely to become anxious about their performance, which may hinder their ability to perform to their full potential. Importantly, the individual does not need to subscribe to the stereotype for it to be activated. It is hypothesized that the mechanism through which anxiety (induced by the activation of the stereotype) decreases performance is by depleting working memory (especially the phonological aspects of the working memory system).

The opposite of stereotype threat is stereotype boost, which is when people perform better than they otherwise would have, because of exposure to positive stereotypes about their social group. A variant of stereotype boost is stereotype lift, which is people achieving better performance because of exposure to negative stereotypes about other social groups.

Some researchers have suggested that stereotype threat should not be interpreted as a factor in real-life performance gaps, and have raised the possibility of publication bias. Other critics have focused on correcting what they claim are misconceptions of early studies showing a large effect. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have shown significant evidence for the effects of stereotype threat, though the phenomenon defies over-simplistic characterization.

Empirical studies

As of 2015, more than 300 studies have been published showing the effects of stereotype threat on performance in a variety of domains. Stereotype threat is considered by some researchers to be a contributing factor to long-standing racial and gender achievement gaps, such as under-performance of black students relative to white ones in various academic subjects, and under-representation of women at higher echelons in the field of mathematics.

The strength of the stereotype threat that occurs depends on how the task is framed. If a task is framed to be neutral, stereotype threat is not likely to occur; however, if tasks are framed in terms of active stereotypes, participants are likely to perform worse on the task. For example, a study on chess players revealed that female players performed more poorly than expected when they were told they would be playing against a male opponent. In contrast, women who were told that their opponent was female performed as would be predicted by past ratings of performance. Female participants who were made aware of the stereotype of females performing worse at chess than males performed worse in their chess games.

A 2007 study extended stereotype threat research to entrepreneurship, a traditionally male-stereotyped profession. The study revealed that stereotype threat can depress women's entrepreneurial intentions while boosting men's intentions. However, when entrepreneurship is presented as a gender-neutral profession, men and women express a similar level of interest in becoming entrepreneurs. Another experiment involved a golf game which was described as a test of "natural athletic ability" or of "sports intelligence". When it was described as a test of athletic ability, European-American students performed worse, but when the description mentioned intelligence, African-American students performed worse.

Other studies have demonstrated how stereotype threat can negatively affect the performance of European Americans in athletic situations as well as the performance of men who are being tested on their social sensitivity. Although the framing of a task can produce stereotype threat in most individuals, certain individuals appear to be more likely to experience stereotype threat than others. Individuals who highly identify with a particular group appear to be more vulnerable to experiencing stereotype threat than individuals who do not identify strongly with the stereotyped group.

The mere presence of other people can evoke stereotype threat. In one experiment, women who took a mathematics exam along with two other women got 70% of the answers right, whereas women who took the same exam in the presence of two men got an average score of 55%.

The goal of a study conducted by Desert, Preaux, and Jund in 2009 was to see if children from lower socioeconomic groups are affected by stereotype threat. The study compared children that were 6–7 years old with children that were 8–9 years old from multiple elementary schools. These children were presented with the Raven's Matrices test, which is an intellectual ability test. Separate groups of children were given directions in an evaluative way and other groups were given directions in a non-evaluative way. The "evaluative" group received instructions that are usually given with the Raven Matrices test, while the "non-evaluative" group was given directions which made it seem as if the children were simply playing a game. The results showed that third graders performed better on the test than the first graders did, which was expected. However, the lower socioeconomic status children did worse on the test when they received directions in an evaluative way than the higher socioeconomic status children did when they received directions in an evaluative way. These results suggested that the framing of the directions given to the children may have a greater effect on performance than socioeconomic status. This was shown by the differences in performance based on which type of instructions they received. This information can be useful in classroom settings to help improve the performance of students of lower socioeconomic status.

There have been studies on the effects of stereotype threat based on age. A study was done on 99 senior citizens ranging in age from 60–75 years. These seniors were given multiple tests on certain factors and categories such as memory and physical abilities, and were also asked to evaluate how physically fit they believe themselves to be. Additionally, they were asked to read articles that contained both positive and negative outlooks about seniors, and they watched someone reading the same articles. The goal of this study was to see if priming the participants before the tests would affect performance. The results showed that the control group performed better than those that were primed with either negative or positive words prior to the tests. The control group seemed to feel more confident in their abilities than the other two groups. Other studies have found that stereotype activation in older adults can improve memory performance, resulting in a distinction between stereotype threat mechanisms in aging compared with other groups.

Many psychological experiments carried out on Stereotype Threat focus on the physiological effects of negative stereotype threat on performance, looking at both high and low status groups. Scheepers and Ellemers tested the following hypothesis: when assessing a performance situation on the basis of current beliefs the low status group members would show a physiological threat response, and high-status members would also show a physiological threat response when examining a possible alteration of the status quo (Scheepers & Ellemers, 2005). The results of this experiment were in line with expectations. As predicted, participants in the low status condition showed higher blood pressure immediately after the status feedback, while participants in the high-status condition showed a spike in blood pressure while anticipating the second round of the task.

In 2012, Scheepers et al. hypothesized that when high social power is stimulated 'an efficient cardiovascular pattern (challenge)' is produced, whereas, 'an inefficient cardiovascular pattern' or threat is caused by the activation of low social power (Scheepers, de Wit, Ellemers & Sassenberg, 2012). Two experiments were carried out in order to test this hypothesis. The first experiment looked at power priming and the second experiment related to role play. Both results from these two experiments provided evidence in support for the hypothesis.

Cleopatra Abdou and Adam Fingerhut were the first to develop experimental methods to study stereotype threat in a health care context, including the first study indicating that health care stereotype threat is linked with adverse health outcomes and disparities.

Some studies have found null results. The single largest experimental test of stereotype threat (N = 2064), conducted on Dutch high school students, found no effect. The authors state, however, that these results are limited to a narrow age-range, experimental procedure and cultural context, and call for further registered reports and replication studies on the topic. Despite these limitations, they state in conclusion that their study shows "that the effects of stereotype threat on math test performance should not be overgeneralized."

Numerous meta-analyses and systematic reviews have shown significant evidence for the effects of stereotype threat. However they also point to ways in which the phenomenon defies over-simplistic characterization. For instance, one meta-analysis found that with female subjects "subtle threat-activating cues produced the largest effect, followed by blatant and moderately explicit cues" while with minorities "moderately explicit stereotype threat-activating cues produced the largest effect, followed by blatant and subtle cues".

Mechanisms

Although numerous studies demonstrate the effects of stereotype threat on performance, questions remain as to the specific cognitive factors that underlie these effects. Steele and Aronson originally speculated that attempts to suppress stereotype-related thoughts lead to anxiety and the narrowing of attention. This could contribute to the observed deficits in performance. In 2008, Toni Schmader, Michael Johns, and Chad Forbes published an integrated model of stereotype threat that focused on three interrelated factors:

- stress arousal;

- performance monitoring, which narrows attention; and,

- efforts to suppress negative thoughts and emotions.

Schmader et al. suggest that these three factors summarize the pattern of evidence that has been accumulated by past experiments on stereotype threat. For example, stereotype threat has been shown to disrupt working memory and executive function, increase arousal, increase self-consciousness about one's performance, and cause individuals to try to suppress negative thoughts as well as negative emotions such as anxiety. People have a limited amount of cognitive resources available. When a large portion of these resources are spent focusing on anxiety and performance pressure, the individual is likely to perform worse on the task at hand.

A number of studies looking at physiological and neurological responses support Schmader and colleagues' integrated model of the processes that produce stereotype threat. Supporting an explanation in terms of stress arousal, one study found that African Americans under stereotype threat exhibit larger increases in arterial blood pressure. One study found increased cardiovascular activation amongst women who watched a video in which men outnumbered women at a math and science conference. Other studies have similarly found that individuals under stereotype threat display increased heart rates. Stereotype threat may also activate a neuroendocrine stress response, as measured by increased levels of cortisol while under threat. The physiological reactions that are induced by stereotype threat can often be subconscious, and can distract and interrupt cognitive focus from the task.

With regard to performance monitoring and vigilance, studies of brain activity have supported the idea that stereotype threat increases both of these processes. Forbes and colleagues recorded electroencephalogram (EEG) signals that measure electrical activity along the scalp, and found that individuals experiencing stereotype threat were more vigilant for performance-related stimuli.

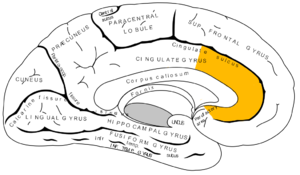

Another study used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to investigate brain activity associated with stereotype threat. The researchers found that women experiencing stereotype threat while taking a math test showed heightened activation in the ventral stream of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a neural region thought to be associated with social and emotional processing. Wraga and colleagues found that women under stereotype threat showed increased activation in the ventral ACC and that the amount of this activation predicted performance decrements on the task. When individuals were made aware of performance-related stimuli, they were more likely to experience stereotype threat. However, a study using fMRI to investigate stereotype threat in older adults showed heightened activation in parietal midline regions including the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and precuneus during both working memory and episodic memory tasks. The heightened activation in these brain areas also was associated with better memory accuracy, inconsistent with the notion that stereotype threat always leads to impaired performance.

A study conducted by Boucher, Rydell, Loo, and Rydell has shown that stereotype threat not only affects performance, but can also affect the ability to learn new information. In the study, undergraduate men and women had a session of learning followed by an assessment of what they learned. Some participants were given information intended to induce stereotype threat, and some of these participants were later given "gender fair" information, which it was predicted would reduce or remove stereotype threat. As a result, participants were split into four separate conditions: control group, stereotype threat only, stereotype threat removed before learning, and stereotype threat removed after learning. The results of the study showed that the women who were presented with the "gender fair" information performed better on the math related test than the women who were not presented with this information. This study also showed that it was more beneficial to women for the "gender fair" information to be presented prior to learning rather than after learning. These results suggest that eliminating stereotype threat prior to taking mathematical tests can help women perform better, and that eliminating stereotype threat prior to mathematical learning can help women learn better.

Original study

In 1995, Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson performed the first experiments demonstrating that stereotype threat can undermine intellectual performance. Steele and Aronson measured this through a word completion task.

They had African-American and European-American college students take a difficult verbal portion of the Graduate Record Examination test. As would be expected based on national averages, the African-American students did not perform as well on the test. Steele and Aronson split students into three groups: stereotype-threat (in which the test was described as being "diagnostic of intellectual ability"), non-stereotype threat (in which the test was described as "a laboratory problem-solving task that was nondiagnostic of ability"), and a third condition (in which the test was again described as nondiagnostic of ability, but participants were asked to view the difficult test as a challenge). All three groups received the same test.

Steele and Aronson concluded that changing the instructions on the test could reduce African-American students' concern about confirming a negative stereotype about their group. Supporting this conclusion, they found that African-American students who regarded the test as a measure of intelligence had more thoughts related to negative stereotypes of their group. Additionally, they found that African Americans who thought the test measured intelligence were more likely to complete word fragments using words associated with relevant negative stereotypes (e.g., completing "__mb" as "dumb" rather than as "numb").

Adjusted for previous SAT scores, subjects in the non-diagnostic-challenge condition performed significantly better than those in the non-diagnostic-only condition and those in the diagnostic condition. In the first experiment, the race-by-condition interaction was marginally significant. However, the second study reported in the same paper found a significant interaction effect of race and condition. This suggested that placement in the diagnostic condition significantly impacted African Americans compared with European Americans.

Stereotype lift and stereotype boost

Stereotype threat concerns how stereotype cues can harm performance. However, in certain situations, stereotype activation can also lead to performance enhancement through stereotype lift or stereotype boost. Stereotype lift increases performance when people are exposed to negative stereotypes about another group. This enhanced performance has been attributed to increases in self-efficacy and decreases in self-doubt as a result of negative outgroup stereotypes. Stereotype boost suggests that positive stereotypes may enhance performance. Stereotype boost occurs when a positive aspect of an individual's social identity is made salient in an identity-relevant domain. Although stereotype boost is similar to stereotype lift in enhancing performance, stereotype lift is the result of a negative outgroup stereotype, whereas stereotype boost occurs due to activation of a positive ingroup stereotype.

Consistent with the positive racial stereotype concerning their superior quantitative skills, Asian American women performed better on a math test when their Asian identity was primed compared to a control condition where no social identity was primed. Conversely, these participants did worse on the math test when instead their gender identity—which is associated with stereotypes of inferior quantitative skills—was made salient, which is consistent with stereotype threat. Two replications of this result have been attempted. In one case, the effect was only reproduced after excluding participants who were unaware of stereotypes about the mathematical abilities of Asians or women, while the other replication failed to reproduce the original results even considering several moderating variables.

Long-term and other consequences

Decreased performance is the most recognized consequence of stereotype threat. However, research has also shown that stereotype threat can cause individuals to blame themselves for perceived failures, self-handicap, discount the value and validity of performance tasks, distance themselves from negatively stereotyped groups, and disengage from situations that are perceived as threatening.

Studies examining stereotype threat in Black Americans have found that when subjects are aware of the stereotype of Black criminality, anxiety about encountering police increases. This, in turn, can lead to self-regulatory efforts, more anxiety, and other behaviors that are commonly perceived as suspicious to police officers. Because police officers tend to perceive Black people as threatening, their reactions to these anxiety-induced behaviors are commonly more harsh than reactions to White people with the same behavior, and influences whether or not they decide to shoot the person.

In the long run, the chronic experience of stereotype threat may lead individuals to disidentify with the stereotyped group. For example, a woman may stop seeing herself as "a math person" after experiencing a series of situations in which she experienced stereotype threat. This disidentification is thought to be a psychological coping strategy to maintain self-esteem in the face of failure. Repeated exposure to anxiety and nervousness can lead individuals to choose to distance themselves from the stereotyped group.

Although much of the research on stereotype threat has examined the effects of coping with negative stereotype on academic performance, recently there has been an emphasis on how coping with stereotype threat could "spillover" to dampen self-control and thereby affect a much broader category of behaviors, even in non-stereotyped domains. Research by Michael Inzlicht and colleagues suggest that, when women cope with negative stereotypes about their math ability, they perform worse on math tests, and that, well after completing the math test, women may continue to show deficits even in unrelated domains. For example, women might overeat, be more aggressive, make more risky decisions, and show less endurance during physical exercise.

The perceived discrimination associated with stereotype threat can also have negative long-term consequences on individuals' mental health. Perceived discrimination has been extensively investigated in terms of its effects on mental health, with a particular emphasis on depression. Cross-sectional studies involving diverse minority groups, including those relating to internalized racism, have found that individuals who experience more perceived discrimination are more likely to exhibit depressive symptoms. Additionally, perceived discrimination has also been found to predict depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. Other negative mental health outcomes associated with perceived discrimination include a reduced general well-being, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and rebellious behavior. A meta-analysis conducted by Pascoe and Smart Richman has shown that the strong link between perceived discrimination and negative mental health persists even after controlling for factors such as education, socioeconomic status, and employment.

Mitigation

Additional research seeks ways to boost the test scores and academic achievement of students in negatively stereotyped groups. Such studies suggest various ways in which the effects of stereotype threat may be mitigated. For example, there have been increasing concerns about the negative effects of stereotype threats on MCAT, SAT, LSAT scores, etc. One effort at mitigation of the negative consequences of stereotype threat involves rescaling standardized test scores to adjust for the adverse effects of stereotypes.

Perhaps most prominently, well replicated findings suggest that teaching students to re-evaluate stress and adopt an incremental theory of intelligence can be an effective way to mitigate the effects of stereotype threat. Two studies sought to measure the effects of persuading participants that intelligence is malleable and can be increased through effort. Both suggested that if people believe that they can improve their performance based on effort, they are more likely to believe that they can overcome negative stereotypes, and thus perform well. Another study found that having students reexamine their situation or anxiety can help their executive resources (attentional control, working memory, etc.), rather than allowing stress to deplete them, and thus improve test performance. Subsequent research has found that students who are taught an incremental view of intelligence do not attribute academic setbacks to their innate ability, but rather to a situational attribute such as a poor study strategy. As a result, students are more likely to implement alternative study strategies and seek help from others.

Research on the power of self-affirmation exercises has shown promising results as well. One such study found that a self-affirmation exercise (in the form of a brief in-class writing assignment about a value that is important to them) significantly improved the grades of African-American middle-school students, and reduced the racial achievement gap by 40%. The authors of this study suggest that the racial achievement gap could be at least partially ameliorated by brief and targeted social-psychological interventions. Another such intervention was attempted with UK medical students, who were given a written assignment and a clinical assessment. For the written assignment group, white students performed worse than minority students. For the clinical assessment, both groups improved their performance, though the gap between racial groups was maintained. Allowing participants to think about a positive value or attribute about themselves prior to completing the task seemed to make them less susceptible to stereotype threat. Self-affirmation has also been shown to mitigate the performance gap between female and male participants on mathematical and geometrical reasoning tests. Similarly, it has been shown that encouraging women to think about their multiple roles and identities by creating self-concept map can eliminate the gender gap on a relatively difficult standardized test. Women given such an opportunity for reflection did equally well as men on the math portion of the GRE, while women who did not create a self-concept map did significantly worse on the math section than men did.

Increasing the representation of minority groups in a field has also been shown to mitigate stereotype threat. In one study, women in STEM fields were shown a video of a conference with either a balanced or unbalanced ratio of men to women. The women viewing an unbalanced ratio reported a lower sense of belonging and less desire to participate. Decreasing cues that reflect only a majority group and increasing cues of minority groups can create environments that mitigate against stereotype threat. Further research has focused on constructing environments such that the physical objects in the environment do not reflect one majority group. For instance, in one study, researchers argued that individuals make decisions about group membership based on the group's environment and showed that altering the physical objects in a room boosted minority participation. In this study, removing stereotypical computer science objects and replacing them with non-stereotypical objects increased female participation in computer science to an equal level as male peers.

Directly communicating that diversity is valued may also be effective. One study revealed that a company's pamphlet stating a direct value of diversity, compared to a color blind approach, caused African Americans to report an increase in trust and comfort towards the company. Promoting cross-group relations between people of varying backgrounds has also been shown to be effective at promoting a sense of belonging among minority group members. For instance, a 2008 study indicates that students have a lower sense of belonging at institutions where they are the minority, but developing friendships with members of other racial groups increased their sense of belonging. In 2007, a study by Greg Walton and Geoffrey Cohen showed results in boosting the grades of African-American college students, and eliminating the racial achievement gap between them and their white peers over the first year of college, by emphasizing to participants that concerns about social belonging tend to lessen over time. These findings suggest that allowing individuals to feel as though they are welcomed into a desirable group makes them more likely to ignore stereotypes. The upshot is that if minority college students are welcomed into the world of academia, they are less likely to be influenced by the negative stereotypes of poor minority performance on academic tasks.

One early study suggested that simply informing college women about stereotype threat and its effects on performance was sufficient to eliminate the predicted gender gap on a difficult math test. The authors of this study argued that making people aware of the fact that they will not necessarily perform worse despite the existence of a stereotype can boost their performance. However, other research has found that merely providing information is not enough, and can even have the opposite effect. In one study, women were given a text "summarizing an experiment in which stereotypes, and not biological differences, were shown to be the cause of women's underperformance in math", and then they performed a math exercise. It was found that "women who properly understood the meaning of the information provided, and thus became knowledgeable about stereotype threat, performed significantly worse at a calculus task". In such cases, further research suggests that the manner in which the information is presented –– that is, whether subjects are made to perceive themselves as targets of negative stereotyping –– may be decisive.

Criticism

Some researchers have argued that stereotype threat should not be interpreted as a factor in real-world achievement gaps. Reviews have raised concerns that the effect might have been over-estimated in the performance of schoolgirls and argued that the field likely suffers from publication bias.

According to Paul R. Sackett, Chaitra M. Hardison, and Michael J. Cullen, both the media and scholarly literature have wrongly concluded that eliminating stereotype threat could completely eliminate differences in test performance between European Americans and African Americans. Sackett et al. argued that, in Steele and Aronson's (1995) experiments where stereotype threat was mitigated, an achievement gap of approximately one standard deviation remained between the groups, which is very close in size to that routinely reported between African American and European Americans' average scores on large-scale standardized tests such as the SAT. In subsequent correspondence between Sackett et al. and Steele and Aronson, Sackett et al. wrote that "They [Steele and Aronson] agree that it is a misinterpretation of the Steele and Aronson (1995) results to conclude that eliminating stereotype threat eliminates the African American-White test-score gap." However, in that same correspondence, Steele and Aronson point out that "it is the stereotype threat conditions, and not the no-threat conditions, that produce group differences most like those of real-life testing."

In a 2009 meta-analysis, Gregory M. Walton and Steven J. Spencer argued that studies of stereotype threat may in fact systematically under-represent its effects, since such studies measure "only that portion of psychological threat that research has identified and remedied. To the extent that unidentified or unremedied psychological threats further undermine performance, the results underestimate the bias." Despite these limitations, they found that efforts to mitigate stereotype threat significantly reduced group differences on high-stakes tests.

In 1998, Arthur R. Jensen criticized stereotype threat theory on the basis that it invokes an additional mechanism to explain effects which could be, according to him, explained by other, at the time better known and more established theories, such as test anxiety and especially the Yerkes–Dodson law. In Jensen's view, the effects which are attributed to stereotype threat may simply reflect "the interaction of ability level with test anxiety as a function of test complexity". However, a subsequent study by Johannes Keller specifically controlled for Jensen's hypothesis and still found significant stereotype threat effects.

Gijsbert Stoet and David C. Geary reviewed the evidence for the stereotype threat explanation of the achievement gap in mathematics between men and women. They concluded that the relevant stereotype threat research has many methodological problems, such as failing to adjust for pre-existing mathematics scores and not having a control group, and that some literature on this topic misrepresents stereotype threat as being more well-established than it is. It was only when using the studies that used adjusted mathematics scores, and not when including the studies that did not make such adjustments, that they found evidence for an effect of stereotype threat.

Publication bias

A meta-analysis by Flore and Wicherts (2015) concluded that the average reported effect of stereotype threat is small, and that those reports may be inflated by publication bias. They argued that, correcting for this, the most likely effect size may be near zero.

Ganley et al. (2013) examined stereotype threat in a well-powered (total number approximately 1000) multi-experiment study and concluded that "no evidence that the mathematics performance of school-age girls was impacted by stereotype threat" was found. Positing that large, well-controlled studies have tended to find smaller or non-significant effects, the authors argued that evidence for stereotype threat in children may reflect publication bias. They also suggested that, among the many underpowered studies run, researchers may have selectively published those in which false-positive effects reached significance.

A 2020 meta-analysis by Liu et al. found that, while publication bias may inflate the effectiveness of interventions to mitigate stereotype threat, the level of bias is insufficient to overturn the consensus that such interventions are associated with performance benefits. The authors broke down the studies they analyzed into three types – belief-based, identity-based, and resilience-based – finding greater evidence for publication bias in the last of these and more robust evidence for the effectiveness of intervention in the first two types.