Liberal socialism has been particularly prominent in British and Italian politics. Its seminal ideas can be traced to John Stuart Mill, who theorised that capitalist societies should experience a gradual process of socialisation through worker-controlled enterprises, coexisting with private enterprises. Mill rejected centralised models of socialism that he thought might discourage competition and creativity, but he argued that representation is essential in a free government and democracy could not subsist if economic opportunities were not well distributed, therefore conceiving democracy not just as a form of representative government, but as an entire social organisation. While some socialists have been hostile to liberalism, accused of "providing an ideological cover for the depredation of capitalism", it has been pointed out that "the goals of liberalism are not so different from those of the socialists", although this similarity in goals has been described as being deceptive due to the different meanings liberalism and socialism give to liberty, equality and solidarity. In a modern context, liberal socialism is sometimes used interchangeably with modern social liberalism or social democracy.

Theory

Liberal socialism opposes laissez-faire-style economic liberalism and state socialism. It considers both liberty and equality as compatible with each other and mutually needed to achieve greater economic equality that is necessary to achieve greater economic liberty. To Polanyi, liberal socialism's goal was overcoming exploitative aspects of capitalism by expropriation of landlords and opening to all the opportunity to own land. It represented the culmination of a tradition initiated by the physiocrats, among others.

Ethical socialism

Ethical socialism is a variant of liberal socialism developed by British socialists. A key component of ethical socialism is in its emphasis on moral and ethical critiques of capitalism and building a case for socialism on moral or spiritual grounds as opposed to rationalist and materialist grounds. Ethical socialists advocated a mixed economy that involves an acceptance of a role of both public enterprise as well as socially responsible private enterprise. Ethical socialism was founded by Christian socialist R. H. Tawney and its ideals were also connected to Fabian and guild-socialist values.

It emphasises the need for a morally conscious economy based upon the principles of service, cooperation and social justice while opposing possessive individualism. Ethical socialism is distinct in its focus on criticism of the ethics of capitalism and not merely criticism of material issues of capitalism. Tawney denounced the self-seeking amoral and immoral behaviour that he claimed is supported by capitalism. He opposed what he called the "acquisitive society" that causes private property to be used to transfer surplus profit to "functionless owners"—capitalist rentiers. However, Tawney did not denounce managers as a whole, believing that management and employees could join together in a political alliance for reform. He supported the pooling of surplus profit through means of progressive taxation to redistribute these funds to provide social welfare, including public health care, public education and public housing.

Tawney advocated nationalisation of strategic industries and services. He also advocated worker participation in the business of management in the economy as well as consumer, employee, employer and state cooperation in the economy. Though he supported a substantial role for public enterprise in the economy, Tawney stated that where private enterprise provided a service that was commensurate with its rewards that was functioning private property, then a business could be usefully and legitimately be left in private hands. Ethical socialist Thomas Hill Green supported the right of equal opportunity for all individuals to be able freely appropriate property, but he claimed that acquisition of wealth did not imply that an individual could do whatever they wanted to once that wealth was in their possession. Green opposed "property rights of the few" that were preventing the ownership of property by the many.

Country by country

Argentina

During the National Autonomist Party governments, liberal socialism emerged in Argentina's politics as opposed to the Julio Argentino Roca's ruling conservative liberalism, though president Domingo Faustino Sarmiento had previously implemented an agenda influenced by John Stuart Mill's writings. The first spokesperson for the new trend was Leandro N. Alem, founder of the Radical Civil Union. Liberal socialists never governed in Argentina, but they constituted the main opposition from 1880 to 1914 and again from 1930 until the rise of Peronism. Adolfo Dickman, Enrique Dickmann, José Ingenieros, Juan B. Justo, Moisés Lebensohn, Alicia Moreau de Justo and Nicolás Repetto are among the representatives of the trend during the Década Infame in the 1930s as part of the Radical Civic Union or the Socialist Party.

Ingenieros' work has diffused all over Latin America. In the 2003 Argentine general election, Ricardo López Murphy (who has declared himself a liberal socialist in the tradition of Alem and Juan Bautista Alberdi) ended third with 16.3 per cent of the popular vote. Contemporary Argentine liberal socialists include Mario Bunge, Carlos Fayt and Juan José Sebreli.

Belgium

Chantal Mouffe is a prominent Belgian advocate of liberal socialism. She describes liberal socialism as follows:

To deepen and enrich the pluralist conquests of liberal democracy, the articulation between political liberalism and individualism must be broken, to make possible a new approach to individuality that restores its social nature without reducing it to a simple component of an organic whole. This is where the socialist tradition of thought might still have something to contribute to the democratic project and herein lies the promise of a liberal socialism.

United Kingdom

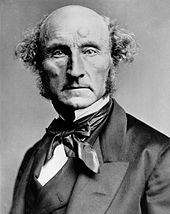

John Stuart Mill

The main classical liberal English thinker John Stuart Mill's early economic philosophy was one of free markets. However, he accepted interventions in the economy. He also accepted the principle of legislative intervention for the purpose of animal welfare. Mill originally believed that equality of taxation meant equality of sacrifice and that progressive taxation penalised those who worked harder and saved more and therefore was a "mild form of robbery".

Given an equal tax rate regardless of income, Mill agreed that inheritance should be taxed. A utilitarian society would agree that everyone should be equal one way or another. Therefore, receiving inheritance would put one ahead of society unless taxed on the inheritance. Those who donate should consider and choose carefully where their money goes—some charities are more deserving than others. Public charities boards such as a government (i.e. social welfare) will disburse the money equally. However, a private charity board like a church would disburse the monies fairly to those who are in more need than others.

Mill later altered his views toward a more socialist bent, adding chapters to his Principles of Political Economy in defence of a socialist outlook and defending some socialist causes. Within this revised work, he also made the radical proposal that the whole wage system be abolished in favour of a co-operative wage system. Nonetheless, some of his views on the idea of flat taxation remained, albeit altered in the third edition of the Principles of Political Economy to reflect a concern for differentiating restrictions on unearned incomes which he favoured; and those on earned incomes which he did not favour.

In the case of Oxford University, Mill's Principles of Political Economy, first published in 1848, was the standard text until 1919 when it was replaced by Alfred Marshall's Principles of Economics. As Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations had during an earlier period, Mill's Principles of Economy dominated economics teaching and was one of the most widely read of all books on economics in the period.

In later editions of Principles of Political Economy, Mill would argue that "as far as economic theory was concerned, there is nothing in principle in economic theory that precludes an economic order based on socialist policies". Mill also promoted substituting capitalist businesses with worker cooperatives, writing:

The form of association, however, which if mankind continue to improve, must be expected in the end to predominate, is not that which can exist between a capitalist as chief, and work-people without a voice in the management, but the association of the labourers themselves on terms of equality, collectively owning the capital with which they carry on their operations, and working under managers elected and removable by themselves.

Ethical socialism in Britain

Liberal socialism has exercised influence in British politics, especially in the variant known as ethical socialism. Ethical socialism is an important ideology of the Labour Party. Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee supported the ideology, which played a large role in his party's policies during the postwar 1940s. Half a century after Attlee's tenure, Tony Blair, another Labour Prime Minister, also described himself as an adherent of ethical socialism, which for him embodies the values of "social justice, the equal worth of each citizen, equality of opportunity, community". Influenced by Attlee and John Macmurray (who himself was influenced by Green), Blair has defined the ideology in similar terms as earlier adherents—with an emphasis on the common good, rights and responsibilities as well as support of an organic society in which individuals flourish through cooperation. Blair argued that Labour ran into problems in the 1960s and 1970s when it abandoned ethical socialism and that its recovery required a return to the values promoted by the Attlee government. However, Blair's critics (both inside and outside Labour) have accused him of completely abandoning socialism in favour of capitalism.

France

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

While Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was a revolutionary, his social revolution did not mean civil war or violent upheaval, but rather the transformation of society. This transformation was essentially moral in nature and demanded the highest ethics from those who sought change. It was monetary reform, combined with organizing a credit bank and workers associations, that Proudhon proposed to use as a lever to bring about the organization of society along new lines. Proudhon's ethical socialism has been described as part of the liberal socialist tradition which is for egalitarianism and free markets, with Proudhon taking "a commitment to narrow down the sphere of activity of the state".

Proudhon was a supporter of both free markets and property, but he distinguished between the privileged private property that he opposed and the earned personal property that he supported. In his in-depth analysis of this aspect of Proudhon's ideas, K. Steven Vincent noted that "Proudhon consistently advanced a program of industrial democracy which would return control and direction of the economy to the workers". For Proudhon, "strong workers' associations [...] would enable the workers to determine jointly by election how the enterprise was to be directed and operated on a day-to-day basis".

Germany

An early version of liberal socialism was developed in Germany by Franz Oppenheimer. Although he was committed to socialism, Oppenheimer's theories inspired the development of the social liberalism that was pursued by German Chancellor Ludwig Erhard, who said the following: "As long as I live, I will not forget Franz Oppenheimer! I will be as happy if the social market economy—as perfect or imperfect as it might be—continues to bear witness to the work, to the intellectual stance of the ideas and teachings of Franz Oppenheimer."

In the 1930s, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), a reformist socialist political party that was up to then based upon revisionist Marxism, began a transition away from orthodox Marxism towards liberal socialism. After it was banned by the Nazi regime in 1933, the SPD acted in exile through the Sopade. In 1934, the Sopade began to publish material that indicated that the SPD was turning towards liberal socialism.

Curt Heyer, a prominent proponent of liberal socialism within the Sopade, declared that Sopade represented the tradition of Weimar Republic social democracy (a form of liberal democratic socialism) and declared that Sopade's held true to its mandate of traditional liberal principles combined with the political realism of socialism. After the restoration of democracy in West Germany, the SPD's Godesberg Program in 1959 eliminated the party's remaining Marxist policies. The SPD then became officially based upon liberal socialism (German: freiheitlicher Sozialismus). West German Chancellor Willy Brandt has been identified as a liberal socialist.

Hungary

In 1919, the Hungarian politician Oszkár Jászi declared his support for what he termed "liberal socialism" while denouncing "communist socialism". Opposed to classical social democracy's prevalent focus on support from the working class, Jászi saw the middle class and smallholder peasants as essential to the development of socialism and spoke of the need of a "radical middle-class". His views were especially influenced by events in Hungary in 1919 involving the Bolshevik revolution and establishment of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, after the collapse of which he specifically denounced the Marxist worldview, calling his views "Anti-Marx". His criticism of orthodox Marxism was centered on its mechanical, valueless, and amoral methodology. He argued that "[i]n no small measure, the present terrible, bewildering world crisis is a consequence of Marxism's mechanical Communism and amoral nihilism. New formulas of spirit, freedom and solidarity have to be found".

Jászi promoted a form of co-operative socialism that included liberal principles of freedom, voluntarism and decentralization. He juxtaposed this ideal version of socialism with the then-existing political system in the Soviet Union, which he identified as being based upon dictatorial and militarist perils, statism, and a crippled economic order where competition and quality are disregarded.

Jászi's views on socialism and works denouncing Bolshevik communism came back into Hungarian public interest in the 1980s when copies of his manuscripts were discovered and were smuggled into Hungary that was then under communist party-rule. Another famous Hungarian politician, Bibó Istvan, was a prolific and unique liberal socialist writer. After the Second World War and the crushing of the Revolution of 1956, he wrote essays from a similar viewpoint. His views were unique in the sense that he had accepted the political system prevalent in the nation at that time, yet remained a follower of liberal and socialist ideas, such as private property and free speech. Therefore, he wished to reconcile them in his works. He felt that Marxism and socialism are (and must be) the road to the goals and ideals of liberalism. ("kisember szocializmus", "kispolgár szocializmus": "little people's socialism" (as white and blue collar worker/lower middle class socialism), "petite bourgeoisie socialism")

Italy

Going back to Italian revolutionaries and socialists such as Giuseppe Garibaldi and Giuseppe Mazzini, Italian socialist Carlo Rosselli was inspired by the definition of socialism by the founder of social democracy, Eduard Bernstein, who defined socialism as "organised liberalism". Rosselli expanded on Bernstein's arguments by developing his notion of liberal socialism (Italian: socialismo liberale). In 1925, Rosselli defined the ideology in his work of the same name in which he supported the type of socialist economy defined by socialist economist Werner Sombart in Der modern Kapitalismus (1908) that envisaged a new modern mixed economy that included both public and private property, limited economic competition and increased economic cooperation.

While appreciating principles of liberalism as an ideology that emphasised liberation, Rosselli was deeply disappointed with liberalism as a system that he described as having been used by the bourgeoisie to support their privileges while neglecting the liberation components of liberalism as an ideology and thus viewed conventional liberalism as a system that had merely become an ideology of "bourgeois capitalism". At the same time, Rosselli appreciated socialism as an ideology, but he was also deeply disappointed with conventional socialism as a system.

In response to his disappointment with conventional socialism in practice, Rosselli declared: "The recent experiences, all the experiences of the past thirty years, have hopelessly condemned the primitive programs of the socialists. State socialism especially—collectivist, centralising socialism—has been defeated". Rosselli's liberal socialism was partly based upon his study and admiration of British political themes of the Fabian Society and John Stuart Mill (he was able to read the English versions of Mill's work On Liberty prior to its availability in Italian that began in 1925). His admiration of British socialism increased after his visit to the United Kingdom in 1923 where he met George Drumgoole Coleman, R. H. Tawney and other members of the Fabian Society.

An important component of Italian liberal socialism developed by Rosselli was its anti-fascism. Rosselli opposed fascism and believed that fascism would only be defeated by a revival of socialism. Rosselli founded Giustizia e Libertà as a resistance movement founded in the 1930s in opposition to the Fascist regime in Italy. Ferruccio Parri—who later became Prime Minister of Italy—and Sandro Pertini—who later became President of Italy—were among Giustizia e Libertà's leaders. Giustizia e Libertà was committed to militant action to fight the Fascist regime and it saw Benito Mussolini as a ruthless murderer who himself deserved to be killed as punishment. Various early schemes were designed by the movement in the 1930s to assassinate Mussolini, including one dramatic plan of using an aircraft to drop a bomb on Piazza Venezia where Mussolini resided. Rosselli was also a prominent member of the liberal-socialist Action Party.

After Rosselli's death, liberal socialism was developed in Italian political thought by Guido Calogero. Unlike Rosselli, Calogero considered the ideology as a unique ideology called liberalsocialism (Italian: liberalsocialismo) that was separate from existing liberal and socialist ideologies. Calogero created the "First Manifesto of Liberalsocialism" in 1940 that stated the following:

At the basis of liberalsocialism stands the concept of the substantial unity and identity of ideal reason, which supports and justifies socialism in its demand for justice as much as it does liberalism in its demand for liberty. This ideal reason coincides with that same ethical principle to whose rule humanity and civilization, both past and future, must always measure up. This is the principle by which we recognize the personhood of others in contrast to our own person and assign to each of them a right to own their own.

After World War II, Ferruccio Parri of the liberal socialist Action Party briefly served as Prime Minister of Italy in 1945. In 1978, liberal socialist Sandro Pertini of the Italian Socialist Party was elected President of Italy in 1978 and served as President until 1985.

Brazil

Lula da Silva (President of Brazil from 2003 to 2010, re-elected President in 2022) set out to show that contemporary 'liberal socialism' can work with the market and capitalism for the benefit of all the people, while promoting public services. While advocating socialism, Lulism aims for a 'social liberal' approach that gradually resolves the gap between the rich and the poor in a market-oriented way.

Iran

In 1904 or 1905, the Social Democratic Party was formed by Persian emigrants in Transcaucasia with the help of local revolutionaries, maintaining close ties to the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party and Hemmat Party. The party created its own mélange of European socialism and indigenous ideas and also upheld liberalism and nationalism. It was the first Iranian socialist organization. It maintained some religious beliefs while being critical of the conservative ulama and embracing separation of church and state. It was founded by Haydar Khan Amo-oghli and led by Nariman Narimanov. Iran Party, another political party that supported both socialism and liberalism, founded by mostly of European-educated technocrats, it advocated "a diluted form of French socialism" (i.e. it "modeled itself on" the moderate Socialist Party of France) and promoted social democracy and liberal nationalism. The socialist tent of the party was more akin to that of the Fabian Society than to the scientific socialism of Karl Marx. Its focus on liberal socialism and democratic socialism principles, made it quite different from pure left-wing parties and it did not show much involvement in labour rights discussions.