It is a reconceptualization of social democracy and is positioned to the right of the centre-left. It supports workfare instead of welfare, work training programs, educational opportunities and other government programs that give citizens a 'hand-up' instead of a 'hand-out'. The Third Way seeks a compromise between a less interventionist economic system as supported by neoliberals and Keynesian Social democratic spending policy supported by social democrats and progressives.

The Third Way was born from a reevaluation of political policies within various centre to centre-left progressive movements in the 1980s in response to doubt regarding the economic viability of the state and the perceived overuse of economic interventionist policies that had previously been popularised by Keynesianism, but which at that time contrasted with the rise of popularity for neoliberalism and the New Right starting in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s.

The Third Way has been promoted by social liberal and social-democratic parties. In the United States, a leading proponent of the Third Way was Bill Clinton, who served as the country's president from 1993 to 2001. In the United Kingdom, Third Way social-democratic proponent Tony Blair claimed that the socialism he advocated was different from traditional conceptions of socialism and said: "My kind of socialism is a set of values based around notions of social justice. ... Socialism as a rigid form of economic determinism has ended, and rightly." Blair referred to it as a "social-ism" involving politics that recognised individuals as socially interdependent and advocated social justice, social cohesion, equal worth of each citizen and equal opportunity.

Third Way social-democratic interpreter Anthony Giddens has said that the Third Way rejects the state socialist conception of socialism and instead accepts the conception of socialism as conceived of by Anthony Crosland as an ethical doctrine that views social democratic governments as having achieved a viable ethical socialism by removing the unjust elements of capitalism by providing social welfare and other policies and that contemporary socialism has outgrown the Marxist claim for the need of the abolition of capitalism as a mode of production. In 2009, Blair publicly declared support for a "new capitalism".

Policies supported by self-purported Third Way supporters vary by region, political circumstances, and ideological leanings. Third Way advocates generally support public-private partnerships, a commitment to fiscal conservatism, combining equality of opportunity with personal responsibility, improving human and social capital, and protection of the environment. But even to these ends Third Way advocates differ due to conflicting priorities. Anthony Giddens for example called for abolishing the retirement age so people can exit the workforce whenever they save enough, believing society should be more inclusive to the elderly; Emmanuel Macron did the exact opposite, raising the retirement age to balance the budget. The Bill Clinton administration, influenced by the works of the controversial political scientist Charles Murray, was less friendly to the welfare state than Tony Blair.

The Third Way has been criticised by other social democrats, as well as anarchists, communists, and in particular democratic socialists as a betrayal of left-wing values, with some analysts characterising the Third Way as an effectively neoliberal movement. It has also been criticised by conservatives, classical liberals, and libertarians who advocate for laissez-faire capitalism.

Overview

Origins

As a term, the third way has been used to explain a variety of political courses and ideologies in the last few centuries. These ideas were implemented by progressives in the early 20th century. The term was picked up again in the 1950s by German ordoliberal economists such as Wilhelm Röpke, resulting in the development of the concept of the social market economy. Röpke later distanced himself from the term and located the social market economy as first way in the sense of an advancement of the free-market economy.

During the Prague Spring of 1968, reform economist Ota Šik proposed third way economic reform as part of political liberalisation and democratisation within the country. In historical context, such proposals were better described as liberalised centrally-planned economy rather than the socially-sensitive capitalism that Third Way policies tend to have been identified with in the West. In the 1970s and 1980s, Enrico Berlinguer, leader of the Italian Communist Party, came to advocate a vision of a socialist society that was more pluralist than the real socialism which was typically advocated by official communist parties whilst being more economically egalitarian than social democracy. This was part of the wider trend of Eurocommunism in the communist movement and provided a theoretical basis for Berlinguer's pursuit of the Historic Compromise with the Christian Democrats.

Modern usage

Third Way politics is visible in Anthony Giddens' works such as Consequences of Modernity (1990), Modernity and Self-Identity (1991), The Transformation of Intimacy (1992), Beyond Left and Right (1994) and The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy (1998). In Beyond Left and Right, Giddens criticises market socialism and constructs a six-point framework for a reconstituted radical politics that includes the following values:

- Repair damaged solidarities.

- Recognise the centrality of life politics.

- Accept that active trust implies generative politics.

- Embrace dialogic democracy.

- Rethink the welfare state.

- Confront violence.

In The Third Way, Giddens provides the framework within which the Third Way, also termed by Giddens as the radical centre, is justified. In addition, it supplies a broad range of policy proposals aimed at what Giddens calls the "progressive centre-left" in British politics.

Bill Clinton espoused the ideas of the Third Way during his 1992 presidential campaign.

The Third Way has been defined as such:

[S]omething different and distinct from liberal capitalism with its unswerving belief in the merits of the free market and democratic socialism with its demand management and obsession with the state. The Third Way is in favour of growth, entrepreneurship, enterprise and wealth creation but it is also in favour of greater social justice and it sees the state playing a major role in bringing this about. So in the words of ... Anthony Giddens of the LSE the Third Way rejects top down socialism as it rejects traditional neo liberalism.

The Third Way has been advocated by its proponents as a "radical-centrist" alternative to both capitalism and what it regards as the traditional forms of socialism, including Marxian and state socialism. It advocates ethical socialism, reformism and gradualism that includes advocating the humanisation of capitalism, a mixed economy, political pluralism and liberal democracy.

The Third Way has been often hard to holistically summarize, partly due to its flexible nature of putting ends before means, that is prioritizing achieving social justice rather than focusing on the methods by which one achieves social justice. Often cited as the easiest summary of the Third Way is 'rights with responsibilities'—for example, pairing the right to education with the responsibility to put effort towards achieving good grades. On economics specifically, a great deal of emphasize of the Third Way is placed on tax revenue, and the means by which it is generated. The Third Way argues that wealth must be enticed in a globalized economy, and that any capital flight caused by high taxes is counterproductive to generating tax revenue, as said tax revenue will be lost. The Third Way argues that growth is the best way to raise tax revenue, and that growth can be achieved through a free market economy, fiscal discipline and a healthy human capital stock.

Within social democracy

The Third Way has been advocated by proponents as competition socialism, an ideology in between traditional socialism and capitalism. Anthony Giddens, a prominent proponent of the Third Way, has publicly supported a modernised form of socialism within the social democracy movement, but he claims that traditional socialist ideology (referring to state socialism) that involves economic management and planning are flawed and states that as a theory of the managed economy it barely exists any longer.

In defining the Third Way, Tony Blair once wrote: "The Third Way stands for a modernised social democracy, passionate in its commitment to social justice".

History

Australia

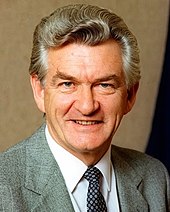

Under the centre-left Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1983 to 1996, the Bob Hawke and Paul Keating governments pursued many economic policies associated with economic rationalism such as floating the Australian Dollar in 1983, reductions in trade tariffs, taxation reforms, changing from centralised wage-fixing to enterprise bargaining, restrictions on trade union activities including on strike action and pattern bargaining, the privatisation of government-run services and enterprises such as Qantas and the Commonwealth Bank and wholesale deregulation of the banking system. Keating also proposed a Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 1985, but this was scrapped due to its unpopularity amongst both ALP and electorate. The party also desisted from other reforms such as wholesale labour market deregulation, the eventual GST, the privatisation of Telstra and welfare reform. The Hawke-Keating governments have been considered by some as laying the groundwork for the later development of both the New Democrats in the United States and New Labour in the United Kingdom. One political commentator agreed that it led centre-left parties towards the path to neoliberalism. Meanwhile, others, particularly former Labor MP and current National President Wayne Swan, acknowledge several economically conservative reforms, but at the same time disagreed and focused on the prosperity and social equality that they provided in the "26 years of uninterrupted economic growth since 1991", seeing it as fitting well within "Australian Laborism". Swan also mentioned the fact that the policies and reforms of the Hawke–Keating governments, described as Third Way, predated the idea by a decade or more.

Both Hawke and Keating made some criticism too. In the lead-up to the 2019 federal election, Hawke made a joint statement with Keating endorsing Labor's economic plan and condemned the Liberal Party for "completely [giving] up the economic reform agenda". They stated that "[Bill] Shorten's Labor is the only party of government focused on the need to modernise the economy to deal with the major challenge of our time: human induced climate change".

Various ideological beliefs were factionalised under reforms to the ALP under Gough Whitlam, resulting in what is now known as the Labor Left, who tend to favour a more interventionist economic policy, more authoritative top-down controls and some socially progressive ideals; and Labor Right, the now dominant faction that is pro-business, more economically liberal and in some cases, more socially conservative.

Former Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd's first speech to parliament in 1998 stated:

Competitive markets are massive and generally efficient generators of economic wealth. They must therefore have a central place in the management of the economy. But markets sometimes fail, requiring direct government intervention through instruments such as industry policy. There are also areas where the public good dictates that there should be no market at all. We are not afraid of a vision in the Labor Party, but nor are we afraid of doing the hard policy yards necessary to turn that vision into reality. Parties of the Centre Left around the world are wrestling with a similar challenge—the creation of a competitive economy while advancing the overriding imperative of a just society. Some call this the "third way". The nomenclature is unimportant. What is important is that it is a repudiation of Thatcherism and its Australian derivatives represented opposite. It is in fact a new formulation of the nation's economic and social imperatives.

While critical of economists such as Friedrich Hayek, Rudd described himself as "basically a conservative when it comes to questions of public financial management", pointing to his slashing of public service jobs as a Queensland governmental advisor. Rudd's government has been praised and credited "by most economists, both local and international, for helping Australia avoiding a post-global-financial-crisis recession" during the Global Recession.

Brazil

Examples of Brazilian Third Way politicians include current Vice President Geraldo Alckmin and former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso. Other politicians include Simone Tebet, José Serra, and to a lesser extent Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Ciro Gomes.

France

Examples of French Third Way politicians include current President Emmanuel Macron, and to a lesser extent François Hollande, Dominique Strauss-Kahn and Manuel Valls.

Germany

Former German chancellor Gerhard Schroder (1998–2005) was a proponent of Third Way policies. Throughout his campaign for chancellor, he portrayed himself as a pragmatic new Social Democrat who would promote economic growth while strengthening Germany's generous social welfare system. During Schröder's time in office, economic growth slowed to only 0.2% in 2002 and Gross Domestic Product shrank in 2003, while German unemployment was over the 10% mark. Most voters soon associated Schröder with the Agenda 2010 reform program, which included cuts in the social welfare system (national health insurance, unemployment payments, pensions), lower taxes, and reformed regulations on employment and payment. He also eliminated capital gains tax on the sale of corporate stocks and thereby made the country more attractive to foreign investors.

Incumbent German chancellor Olaf Scholz (2021–present) has not explicitly stated support for Third way policies, but is widely seen as part of the moderate wing of within the SPD. During his tenure as minister of finance in the Fourth Merkel cabinet (2018–2021), Scholz prioritized not taking on new government debt and limiting public spending.

Italy

The Italian Democratic Party is a plural social democratic party including several distinct ideological trends. Politicians such as former Prime Ministers Romano Prodi and Matteo Renzi are proponents of the Third Way. Renzi has occasionally been compared to former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair for his political views. Renzi himself has previously claimed to be a supporter of Blair's ideology of the Third Way, regarding an objective to synthesise liberal economics and left-wing social policies.

Under Renzi's secretariat, the Democratic Party took a strong stance in favour of constitutional reform and of a new electoral law on the road toward a two-party system. It is not an easy task to find the exact political trend represented by Renzi and his supporters, who have been known as Renziani. The nature of Renzi's progressivism is a matter of debate and has been linked both to liberalism and populism. According to Maria Teresa Meli of Corriere della Sera, Renzi "pursues a precise model, borrowed from the Labour Party and Bill Clinton's Democratic Party", comprising "a strange mix (for Italy) of liberal policy in the economic sphere and populism. This means that on one side he will attack the privileges of trade unions, especially of the CGIL, which defends only the already protected, while on the other he will sharply attack the vested powers, bankers, Confindustria and a certain type of capitalism".

After the Democratic Party's defeat in the 2018 general election in which the party gained 18.8% and 19.1% of the vote (down from 25.5% and 27.4% in 2013) and lost 185 deputies and 58 senators, respectively, Renzi resigned as the party's secretary. In March 2019, Nicola Zingaretti, a social democrat and prominent member of the party's left-wing with solid roots in the Italian Communist Party, won the leadership election by a landslide, defeating Maurizio Martina (Renzi's former deputy secretary) and Roberto Giachetti (supported by most Renziani). Zingaretti focused his campaign on a clear contrast with Renzi's policies and his victory opened the way for a new party.

In September 2019, Renzi announced his intention to leave the Democratic Party and create a new parliamentary group. He officially launched Italia Viva to continue the liberal and Third Way tradition within a pro-Europeanism framework, especially as represented by the French President Emmanuel Macron's La République En Marche!.

United Kingdom

In 1939, Harold Macmillan wrote a book entitled The Middle Way, advocating a compromise between capitalism and socialism which was a precursor to the contemporary notion of the Third Way.

In 1979, the Labour Party professed a complete adherence to social democratic ideals and rejected the choice between a "prosperous and efficient Britain" and a "caring and compassionate Britain". Coherent with this position, the main commitment of the party was the reduction of economic inequality via the introduction of a wealth tax. This was rejected in the 1997 manifesto, along with many changes in the 1990s like the progressive dismissal of traditional social democratic ideology and the transformation into New Labour, de-emphasising the need to tackle economic inequality and focusing instead on the expansion of opportunities for all whilst fostering social capital.

Former Prime Minister Tony Blair is cited as a Third Way politician. According to a former member of Blair's staff, Blair and the Labour Party learnt from and owes a debt to Bob Hawke's government in Australia in the 1980s on how to govern as a Third Way party. Blair wrote in a Fabian pamphlet in 1994 of the existence of two prominent variants of socialism, namely one based on a Marxist–Leninist economic determinist and collectivist tradition and the other being an ethical socialism based on values of "social justice, the equal worth of each citizen, equality of opportunity, community". Blair is a particular follower of the ideas and writings of Giddens.

In 1998, Blair, then Labour Party Leader and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, described the Third Way, how it relates to social democracy and its relation with both the Old Left and the New Right, as follows:

The Third Way stands for a modernised social democracy, passionate in its commitment to social justice and the goals of the centre-left. ... But it is a third way because it moves decisively beyond an Old Left preoccupied by state control, high taxation and producer interests; and a New Right treating public investment, and often the very notions of "society" and collective endeavour, as evils to be undone.

In 2002, Anthony Giddens listed problems facing the New Labour government, naming spin as the biggest failure because its damage to the party's image was difficult to rebound from. He also challenged the failure of the Millennium Dome project and Labour's inability to deal with irresponsible businesses. Giddens saw Labour's ability to marginalise the Conservative Party as a success as well its economic policy, welfare reform and certain aspects of education. Giddens criticised what he called Labour's "half-way houses", including the National Health Service and environmental and constitutional reform.

In 2008, Charles Clarke, a former United Kingdom Home Secretary and the first senior Blairite to attack Prime Minister Gordon Brown openly and in print, stated: "We should discard the techniques of 'triangulation' and 'dividing lines' with the Conservatives, which lead to the not entirely unjustified charge that we simply follow proposals from the Conservatives or the right-wing media, to minimise differences and remove lines of attack against us".

Brown was succeeded by Ed Miliband's One Nation Labour in 2010 and self-described democratic socialist Jeremy Corbyn in 2015 as the Leader of the Labour Party. This led some to comment that New Labour is "dead and buried". Keir Starmer, now the Prime Minister, succeeded Corbyn in 2020, and has since reverted on his initial more left-wing pledges, in favour policies more associated with New Labour.

The Third Way as practised under New Labour has been criticised as being effectively a new, centre-right and neoliberal party. Some such as Glen O'Hara have argued that while containing "elements that we could term neoliberal", New Labour was more left-leaning than it is given credit for.

United States

In the United States, Third Way adherents historically embraced fiscal conservatism to a greater extent than traditional economic liberals, advocated for some replacement of welfare with workfare, and sometimes held a stronger preference for market solutions to traditional problems (as in pollution markets) while rejecting pure laissez-faire economics and other libertarian positions. The Third Way style of governing was firmly adopted and partly redefined during the administration of President Bill Clinton.

As a term, it was introduced by political scientist Stephen Skowronek. Third Way presidents "undermine the opposition by borrowing policies from it in an effort to seize the middle and with it to achieve political dominance". Examples of this are Richard Nixon's economic policies, which were a continuation of Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society, as well as Clinton's welfare reform later.

Along with Blair, Prodi, Gerhard Schröder and other leading Third Way adherents, Clinton organised conferences to promote the Third Way philosophy in 1997 at Chequers in England. The Third Way think tank and the Democratic Leadership Council are adherents of Third Way politics.

In 2013, American lawyer and former bank regulator William K. Black criticized then-extant Third Way movements: "Third Way is this group that pretends sometimes to be centre-left but is actually completely a creation of Wall Street—it's run by Wall Street for Wall Street with this false flag operation as if it were a center-left group. It's nothing of the sort".

Other countries

Other leaders who have adopted elements of the Third Way style of governance include:

- Edi Rama in

Albania

Albania - Fernando de la Rúa in

Argentina

Argentina - Viktor Klima and Alfred Gusenbauer in

Austria

Austria - Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (only his first term) in

Brazil

Brazil - Kiril Petkov in

Bulgaria

Bulgaria - Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin in

Canada

Canada - Ricardo Lagos and Michelle Bachelet (only her first term) in

Chile

Chile - Juan Manuel Santos in

Colombia

Colombia - Óscar Arias, José María Figueres, Laura Chinchilla, Carlos Alvarado Quesada, Luis Guillermo Solís and Rodrigo Chaves Robles in

Costa Rica

Costa Rica - Vlado Gotovac in

Croatia

Croatia - Helle Thorning-Schmidt in

Denmark

Denmark - Leonel Fernández, Hipólito Mejía, Danilo Medina and Luis Abinader in the

Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic - Rodrigo Borja Cevallos, Abdalá Bucaram, Lucio Gutiérrez and Lenín Moreno in

Ecuador

Ecuador - Paavo Lipponen in

Finland

Finland - Gerhard Schröder and Olaf Scholz in

Germany

Germany - Costas Simitis in

Greece

Greece - Álvaro Colom in

Guatemala

Guatemala - Ferenc Gyurcsány in

Hungary

Hungary - Ehud Barak, Ehud Olmert and Yair Lapid in

Israel

Israel - Muammar Gaddafi in

Libya

Libya - Joseph Muscat and Robert Abela in

Malta

Malta - Ernesto Zedillo in

Mexico

Mexico - Milo Đukanović in

Montenegro

Montenegro - Wim Kok in

Netherlands

Netherlands - Helen Clark in

New Zealand

New Zealand - Ernesto Pérez Balladares, Martín Torrijos and Laurentino Cortizo in

Panama

Panama - Alan García, Alejandro Toledo and Ollanta Humala in

Peru

Peru - António Guterres and José Sócrates in

Portugal

Portugal - Borut Pahor in

Slovenia

Slovenia - Thabo Mbeki in

South Africa

South Africa - Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun in

South Korea

South Korea - Ingvar Carlsson and Göran Persson in

Sweden

Sweden - Thaksin Shinawatra in

Thailand

Thailand - Carlos Andrés Pérez (only his second term) in

Venezuela

Venezuela

Recent developments

By the 2010s, social democratic parties that accepted Third Way politics such as triangulation and the neoliberal shift in policies such as austerity, deregulation, free trade, privatisation and welfare reforms such as workfare experienced a drastic decline as the Third Way had largely fallen out of favour in a phenomenon known as Pasokification. Scholars have linked the decline of social democratic parties to the declining number of industrial workers, greater economic prosperity of voters and a tendency for these parties to shift closer to the centre-right on economic issues, alienating their former base of supporters and voters. This decline has been matched by increased support for more left-wing and populist parties as well as Left and Green social-democratic parties that rejected neoliberal and Third Way policies.

Democratic socialism has emerged in opposition to Third Way social democracy on the basis that democratic socialists are committed to systemic transformation of the economy from capitalism to socialism whereas social-democratic supporters of the Third Way were more concerned about challenging the New Right and win social democracy back to power. This has resulted in analysts and critics alike arguing that in effect it endorsed capitalism, even if it was due to recognising that outspoken opposition to capitalism in these circumstances was politically nonviable; and that it was anti-social democratic in practice. Others saw it as theoretically fitting with modern socialism, especially liberal socialism, distinguishing it from both classical socialism and traditional democratic socialism or social democracy.

Third Way economic policies began to be challenged following the Great Recession, and the rise of right-wing populism has put the ideology into question. Many on the left have become more vocal in opposition to the Third Way, with the most prominent example in the United Kingdom being the rise of self-identified democratic socialist former Labour Party Leader Jeremy Corbyn as well as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders in the United States.

Criticism

The Third Way has been criticized as being a vague ideology with no specific commitments:

The Third Way is no more than a crude attempt to construct a bogus coalition between the haves and the haves not: Bogus because it entices the haves by assuring them that the economy will be sound and their interests would not be threatened, while promising the have-nots a world free from poverty and injustice. Based on opportunism, it has no ideological commitment at all.

After the dismantling of his country's Marxist–Leninist government, Czechoslovakia's conservative finance minister Václav Klaus declared in 1990: "We want a market economy without any adjectives. Any compromises with that will only fuzzy up the problems we have. To pursue a so-called 'third way' [between central planning and the market economy] is foolish. We had our experience with this in the 1960s when we looked for a socialism with a human face. It did not work, and we must be explicit that we are not aiming for a more efficient version of a system that has failed. The market is indivisible; it cannot be an instrument in the hands of central planners".

Left-wing opponents of the Third Way argue that it represents social democrats who responded to the New Right by accepting capitalism. The Third Way most commonly uses market mechanics and private ownership of the means of production and in that sense it is fundamentally capitalist. In addition to opponents who have noticed this, other reviews have claimed that Third Way social democrats adjusted to the political climate since the 1980s that favoured capitalism by recognising that outspoken opposition to capitalism in these circumstances was politically nonviable and that accepting capitalism as the current status quo and seeking to administer it to challenge laissez-faire liberals was a more pressing immediate concern. With the rise of neoliberalism in the late 1970s and early 1980s and the Third Way between the 1990s and 2000s, social democracy became synonymous with it. As a result, the section of social democracy that remained committed to the gradual abolition of capitalism and opposed the Third Way merged into democratic socialism. Many social democrats opposed to the Third Way overlap with democratic socialists in their committiment to an alternative to capitalism and a post-capitalist economy and have not only criticised the Third Way as anti-socialist and neoliberal, but also as anti-social-democratic in practice.

Democratic and market socialists argue that the major reason for the economic shortcomings of command economies was their authoritarian nature rather than socialism itself, that it was a failure of a specific model and that therefore socialists should support democratic models rather than abandon it. Economists Pranab Bardhan and John Roemer argue that Soviet-type economies and Marxist–Leninist states failed because they did not create rules and operational criteria for the efficient operation of state enterprises in their administrative, command allocation of resources and commodities and the lack of democracy in the political systems that the Soviet-type economies were combined with. According to them, a form of competitive socialism that rejects dictatorship and authoritarian allocation in favor of democracy could work and prove superior to the market economy.

Although close to New Labour and a key figure in the development of the Third Way, sociologist Anthony Giddens dissociated himself from many of the interpretations of the Third Way made in the sphere of day-to-day politics. For him, it was not a succumbing to neoliberalism or the dominance of capitalist markets. The point was to get beyond both market fundamentalism and top-down socialism—to make the values of the centre-left count in a globalising world. He argued that "the regulation of financial markets is the single most pressing issue in the world economy" and that "global commitment to free trade depends upon effective regulation rather than dispenses with the need for it".