An essay is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a letter, a paper, an article, a pamphlet, and a short story. Essays have been sub-classified as formal and informal: formal essays are characterized by "serious purpose, dignity, logical organization, length," whereas the informal essay is characterized by "the personal element (self-revelation, individual tastes and experiences, confidential manner), humor, graceful style, rambling structure, unconventionality or novelty of theme," etc.

Essays are commonly used as literary criticism, political manifestos, learned arguments, observations of daily life, recollections, and reflections of the author. Almost all modern essays are written in prose, but works in verse have been dubbed essays (e.g., Alexander Pope's An Essay on Criticism and An Essay on Man). While brevity usually defines an essay, voluminous works like John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding and Thomas Malthus's An Essay on the Principle of Population are counterexamples.

In some countries (e.g., the United States and Canada), essays have become a major part of formal education. Secondary students are taught structured essay formats to improve their writing skills; admission essays are often used by universities in selecting applicants, and in the humanities and social sciences essays are often used as a way of assessing the performance of students during final exams.

The concept of an "essay" has been extended to other media beyond writing. A film essay is a movie that often incorporates documentary filmmaking styles and focuses more on the evolution of a theme or idea. A photographic essay covers a topic with a linked series of photographs that may have accompanying text or captions.

Definitions

The word essay derives from the French infinitive essayer, "to try" or "to attempt". In English essay first meant "a trial" or "an attempt", and this is still an alternative meaning. The Frenchman Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) was the first author to describe his work as essays; he used the term to characterize these as "attempts" to put his thoughts into writing.

Subsequently, essay has been defined in a variety of ways. One definition is a "prose composition with a focused subject of discussion" or a "long, systematic discourse". It is difficult to define the genre into which essays fall. Aldous Huxley, a leading essayist, gives guidance on the subject. He notes that "the essay is a literary device for saying almost everything about almost anything", and adds that "by tradition, almost by definition, the essay is a short piece". Furthermore, Huxley argues that "essays belong to a literary species whose extreme variability can be studied most effectively within a three-poled frame of reference". These three poles (or worlds in which the essay may exist) are:

- The personal and the autobiographical: The essayists that feel most comfortable in this pole "write fragments of reflective autobiography and look at the world through the keyhole of anecdote and description".

- The objective, the factual, and the concrete particular: The essayists that write from this pole "do not speak directly of themselves, but turn their attention outward to some literary or scientific or political theme. Their art consists of setting forth, passing judgment upon, and drawing general conclusions from the relevant data".

- The abstract-universal: In this pole "we find those essayists who do their work in the world of high abstractions", who are never personal and who seldom mention the particular facts of experience.

Huxley adds that the most satisfying essays "...make the best not of one, not of two, but of all the three worlds in which it is possible for the essay to exist."

History

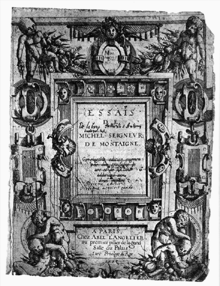

Montaigne

Montaigne's "attempts" grew out of his commonplacing. Inspired in particular by the works of Plutarch, a translation of whose Œuvres Morales (Moral works) into French had just been published by Jacques Amyot, Montaigne began to compose his essays in 1572; the first edition, entitled Essais, was published in two volumes in 1580. For the rest of his life, he continued revising previously published essays and composing new ones. A third volume was published posthumously; together, their over 100 examples are widely regarded as the predecessor of the modern essay.

Europe

While Montaigne's philosophy was admired and copied in France, none of his most immediate disciples tried to write essays. But Montaigne, who liked to fancy that his family (the Eyquem line) was of English extraction, had spoken of the English people as his "cousins", and he was early read in England, notably by Francis Bacon.

Bacon's essays, published in book form in 1597 (only five years after the death of Montaigne, containing the first ten of his essays), 1612, and 1625, were the first works in English that described themselves as essays. Ben Jonson first used the word essayist in 1609, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. Other English essayists included Sir William Cornwallis, who published essays in 1600 and 1617 that were popular at the time, Robert Burton (1577–1641) and Sir Thomas Browne (1605–1682). In Italy, Baldassare Castiglione wrote about courtly manners in his essay Il Cortigiano. In the 17th century, the Spanish Jesuit Baltasar Gracián wrote about the theme of wisdom.

In England, during the Age of Enlightenment, essays were a favored tool of polemicists who aimed at convincing readers of their position; they also featured heavily in the rise of periodical literature, as seen in the works of Joseph Addison, Richard Steele and Samuel Johnson. Addison and Steele used the journal Tatler (founded in 1709 by Steele) and its successors as storehouses of their work, and they became the most celebrated eighteenth-century essayists in England. Johnson's essays appear during the 1750s in various similar publications. As a result of the focus on journals, the term also acquired a meaning synonymous with "article", although the content may not the strict definition. On the other hand, Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding is not an essay at all, or cluster of essays, in the technical sense, but still it refers to the experimental and tentative nature of the inquiry which the philosopher was undertaking.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Edmund Burke and Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote essays for the general public. The early 19th century, in particular, saw a proliferation of great essayists in English—William Hazlitt, Charles Lamb, Leigh Hunt and Thomas De Quincey all penned numerous essays on diverse subjects, reviving the earlier graceful style. Thomas Carlyle's essays were highly influential, and one of his readers, Ralph Waldo Emerson, became a prominent essayist himself. Later in the century, Robert Louis Stevenson also raised the form's literary level. In the 20th century, a number of essayists, such as T.S. Eliot, tried to explain the new movements in art and culture by using essays. Virginia Woolf, Edmund Wilson, and Charles du Bos wrote literary criticism essays.

In France, several writers produced longer works with the title of essai that were not true examples of the form. However, by the mid-19th century, the Causeries du lundi, newspaper columns by the critic Sainte-Beuve, are literary essays in the original sense. Other French writers followed suit, including Théophile Gautier, Anatole France, Jules Lemaître and Émile Faguet.

Japan

As with the novel, essays existed in Japan several centuries before they developed in Europe with a genre of essays known as zuihitsu—loosely connected essays and fragmented ideas. Zuihitsu have existed since almost the beginnings of Japanese literature. Many of the most noted early works of Japanese literature are in this genre. Notable examples include The Pillow Book (c. 1000), by court lady Sei Shōnagon, and Tsurezuregusa (1330), by particularly renowned Japanese Buddhist monk Yoshida Kenkō. Kenkō described his short writings similarly to Montaigne, referring to them as "nonsensical thoughts" written in "idle hours". Another noteworthy difference from Europe is that women have traditionally written in Japan, though the more formal, Chinese-influenced writings of male writers were more prized at the time.

China

The eight-legged essay (Chinese: 八股文; pinyin: bāgǔwén; lit. 'eight bone text') was a style of essay in imperial examinations during the Ming and Qing dynasties in China. The eight-legged essay was needed for those test takers in these civil service tests to show their merits for government service, often focusing on Confucian thought and knowledge of the Four Books and Five Classics, in relation to governmental ideals. Test takers could not write in innovative or creative ways, but needed to conform to the standards of the eight-legged essay. Various skills were examined, including the ability to write coherently and to display basic logic. In certain times, the candidates were expected to spontaneously compose poetry upon a set theme, whose value was also sometimes questioned, or eliminated as part of the test material. This was a major argument in favor of the eight-legged essay, arguing that it were better to eliminate creative art in favor of prosaic literacy. In the history of Chinese literature, the eight-legged essay is often said to have caused China's "cultural stagnation and economic backwardness" in the 19th century.

Forms and styles

This section describes the different forms and styles of essay writing. These are used by an array of authors, including university students and professional essayists.

Cause and effect

The defining features of a "cause and effect" essay are causal chains that connect from a cause to an effect, careful language, and chronological or emphatic order. A writer using this rhetorical method must consider the subject, determine the purpose, consider the audience, think critically about different causes or consequences, consider a thesis statement, arrange the parts, consider the language, and decide on a conclusion.

Classification and division

Classification is the categorization of objects into a larger whole while division is the breaking of a larger whole into smaller parts.

Compare and contrast

Compare and contrast essays are characterized by a basis for comparison, points of comparison, and analogies. It is grouped by the object (chunking) or by point (sequential). The comparison highlights the similarities between two or more similar objects while contrasting highlights the differences between two or more objects. When writing a compare/contrast essay, writers need to determine their purpose, consider their audience, consider the basis and points of comparison, consider their thesis statement, arrange and develop the comparison, and reach a conclusion. Compare and contrast is arranged emphatically.

Expository

An expository essay is used to inform, describe or explain a topic, using important facts to teach the reader about a topic. Mostly written in third-person, using "it", "he", "she", "they," the expository essay uses formal language to discuss someone or something. Examples of expository essays are: a medical or biological condition, social or technological process, life or character of a famous person. The writing of an expository essay often consists of the following steps: organizing thoughts (brainstorming), researching a topic, developing a thesis statement, writing the introduction, writing the body of essay, and writing the conclusion. Expository essays are often assigned as a part of SAT and other standardized testing or as homework for high school and college students.

Descriptive

Descriptive writing is characterized by sensory details, which appeal to the physical senses, and details that appeal to a reader's emotional, physical, or intellectual sensibilities. Determining the purpose, considering the audience, creating a dominant impression, using descriptive language, and organizing the description are the rhetorical choices to consider when using a description. A description is usually arranged spatially but can also be chronological or emphatic. The focus of a description is the scene. Description uses tools such as denotative language, connotative language, figurative language, metaphor, and simile to arrive at a dominant impression. One university essay guide states that "descriptive writing says what happened or what another author has discussed; it provides an account of the topic". Lyric essays are an important form of descriptive essays.

Dialectic

In the dialectic form of the essay, which is commonly used in philosophy, the writer makes a thesis and argument, then objects to their own argument (with a counterargument), but then counters the counterargument with a final and novel argument. This form benefits from presenting a broader perspective while countering a possible flaw that some may present. This type is sometimes called an ethics paper.

Exemplification

An exemplification essay is characterized by a generalization and relevant, representative, and believable examples including anecdotes. Writers need to consider their subject, determine their purpose, consider their audience, decide on specific examples, and arrange all the parts together when writing an exemplification essay.

Familiar

An essayist writes a familiar essay if speaking to a single reader, writing about both themselves, and about particular subjects. Anne Fadiman notes that "the genre's heyday was the early nineteenth century," and that its greatest exponent was Charles Lamb. She also suggests that while critical essays have more brain than the heart, and personal essays have more heart than brain, familiar essays have equal measures of both.

History (thesis)

A history essay sometimes referred to as a thesis essay describes an argument or claim about one or more historical events and supports that claim with evidence, arguments, and references. The text makes it clear to the reader why the argument or claim is as such.

Narrative

A narrative uses tools such as flashbacks, flash-forwards, and transitions that often build to a climax. The focus of a narrative is the plot. When creating a narrative, authors must determine their purpose, consider their audience, establish their point of view, use dialogue, and organize the narrative. A narrative is usually arranged chronologically.

Argumentative

An argumentative essay is a critical piece of writing, aimed at presenting objective analysis of the subject matter, narrowed down to a single topic. The main idea of all the criticism is to provide an opinion either of positive or negative implication. As such, a critical essay requires research and analysis, strong internal logic and sharp structure. Its structure normally builds around introduction with a topic's relevance and a thesis statement, body paragraphs with arguments linking back to the main thesis, and conclusion. In addition, an argumentative essay may include a refutation section where conflicting ideas are acknowledged, described, and criticized. Each argument of an argumentative essay should be supported with sufficient evidence, relevant to the point.

Process

A process essay is used for an explanation of making or breaking something. Often, it is written in chronological order or numerical order to show step-by-step processes. It has all the qualities of a technical document with the only difference is that it is often written in descriptive mood, while a technical document is mostly in imperative mood.

Economic

An economic essay can start with a thesis, or it can start with a theme. It can take a narrative course and a descriptive course. It can even become an argumentative essay if the author feels the need. After the introduction, the author has to do his/her best to expose the economic matter at hand, to analyze it, evaluate it, and draw a conclusion. If the essay takes more of a narrative form then the author has to expose each aspect of the economic puzzle in a way that makes it clear and understandable for the reader

Reflective

A reflective essay is an analytical piece of writing in which the writer describes a real or imaginary scene, event, interaction, passing thought, memory, or form—adding a personal reflection on the meaning of the topic in the author's life. Thus, the focus is not merely descriptive. The writer doesn't just describe the situation, but revisits the scene with more detail and emotion to examine what went well, or reveal a need for additional learning—and may relate what transpired to the rest of the author's life.

Other logical structures

The logical progression and organizational structure of an essay can take many forms. Understanding how the movement of thought is managed through an essay has a profound impact on its overall cogency and ability to impress. A number of alternative logical structures for essays have been visualized as diagrams, making them easy to implement or adapt in the construction of an argument.

Academic

In countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, essays have become a major part of a formal education in the form of free response questions. Secondary students in these countries are taught structured essay formats to improve their writing skills, and essays are often used by universities in these countries in selecting applicants (see admissions essay). In both secondary and tertiary education, essays are used to judge the mastery and comprehension of the material. Students are asked to explain, comment on, or assess a topic of study in the form of an essay. In some courses, university students must complete one or more essays over several weeks or months. In addition, in fields such as the humanities and social sciences, mid-term and end of term examinations often require students to write a short essay in two or three hours.

In these countries, so-called academic essays, also called papers, are usually more formal than literary ones. They may still allow the presentation of the writer's own views, but this is done in a logical and factual manner, with the use of the first person often discouraged. Longer academic essays (often with a word limit of between 2,000 and 5,000 words) are often more discursive. They sometimes begin with a short summary analysis of what has previously been written on a topic, which is often called a literature review.

Longer essays may also contain an introductory page that defines words and phrases of the essay's topic. Most academic institutions require that all substantial facts, quotations, and other supporting material in an essay be referenced in a bibliography or works cited page at the end of the text. This scholarly convention helps others (whether teachers or fellow scholars) to understand the basis of facts and quotations the author uses to support the essay's argument. The bibliography also helps readers evaluate to what extent the argument is supported by evidence and to evaluate the quality of that evidence. The academic essay tests the student's ability to present their thoughts in an organized way and is designed to test their intellectual capabilities.

One of the challenges facing universities is that in some cases, students may submit essays purchased from an essay mill (or "paper mill") as their own work. An "essay mill" is a ghostwriting service that sells pre-written essays to university and college students. Since plagiarism is a form of academic dishonesty or academic fraud, universities and colleges may investigate papers they suspect are from an essay mill by using plagiarism detection software, which compares essays against a database of known mill essays and by orally testing students on the contents of their papers.

Magazine or newspaper

Essays often appear in magazines, especially magazines with an intellectual bent, such as The Atlantic and Harpers. Magazine and newspaper essays use many of the essay types described in the section on forms and styles (e.g., descriptive essays, narrative essays, etc.). Some newspapers also print essays in the op-ed section.

Employment

Employment essays detailing experience in a certain occupational field are required when applying for some jobs, especially government jobs in the United States. Essays known as Knowledge Skills and Executive Core Qualifications are required when applying to certain US federal government positions.

A KSA, or "Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities", is a series of narrative statements that are required when applying to Federal government job openings in the United States. KSAs are used along with resumes to determine who the best applicants are when several candidates qualify for a job. The knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary for the successful performance of a position are contained on each job vacancy announcement. KSAs are brief and focused essays about one's career and educational background that presumably qualify one to perform the duties of the position being applied for.

An Executive Core Qualification, or ECQ, is a narrative statement that is required when applying to Senior Executive Service positions within the US Federal government. Like the KSAs, ECQs are used along with resumes to determine who the best applicants are when several candidates qualify for a job. The Office of Personnel Management has established five executive core qualifications that all applicants seeking to enter the Senior Executive Service must demonstrate.

Non-literary types

Film

A film essay (also essay film or cinematic essay) consists of the evolution of a theme or an idea rather than a plot per se, or the film literally being a cinematic accompaniment to a narrator reading an essay. From another perspective, an essay film could be defined as a documentary film visual basis combined with a form of commentary that contains elements of self-portrait (rather than autobiography), where the signature (rather than the life story) of the filmmaker is apparent. The cinematic essay often blends documentary, fiction, and experimental film making using tones and editing styles.

The genre is not well-defined but might include propaganda works of early Soviet filmmakers like Dziga Vertov, present-day filmmakers including Chris Marker, Michael Moore (Roger & Me, Bowling for Columbine and Fahrenheit 9/11), Errol Morris (The Thin Blue Line), Morgan Spurlock (Supersize Me) and Agnès Varda. Jean-Luc Godard describes his recent work as "film-essays". Two filmmakers whose work was the antecedent to the cinematic essay include Georges Méliès and Bertolt Brecht. Méliès made a short film (The Coronation of Edward VII (1902)) about the 1902 coronation of King Edward VII, which mixes actual footage with shots of a recreation of the event. Brecht was a playwright who experimented with film and incorporated film projections into some of his plays. Orson Welles made an essay film in his own pioneering style, released in 1974, called F for Fake, which dealt specifically with art forger Elmyr de Hory and with the themes of deception, "fakery", and authenticity in general.

David Winks Gray's article "The essay film in action" states that the "essay film became an identifiable form of filmmaking in the 1950s and '60s". He states that since that time, essay films have tended to be "on the margins" of the filmmaking the world. Essay films have a "peculiar searching, questioning tone ... between documentary and fiction" but without "fitting comfortably" into either genre. Gray notes that just like written essays, essay films "tend to marry the personal voice of a guiding narrator (often the director) with a wide swath of other voices". The University of Wisconsin Cinematheque website echoes some of Gray's comments; it calls a film essay an "intimate and allusive" genre that "catches filmmakers in a pensive mood, ruminating on the margins between fiction and documentary" in a manner that is "refreshingly inventive, playful, and idiosyncratic".

Video

Video essays are an emerging media type similar to film essays. Video essays have gained significant prominence on YouTube, as YouTube's policies on free uploads of arbitrary lengths have made it a hotbed. Some video essays feature long, documentary style writing and editing, going deep into the research and history of a particular topic. Others are more akin to an argumentative essay in which a single argument is developed and supported throughout the video. Video essay styles have become especially prominent among BreadTube creators such as ContraPoints and PhilosophyTube.

Music

In the realm of music, composer Samuel Barber wrote a set of "Essays for Orchestra", relying on the form and content of the music to guide the listener's ear, rather than any extra-musical plot or story.

Photography

A photographic essay strives to cover a topic with a linked series of photographs. Photo essays range from purely photographic works to photographs with captions or small notes to full-text essays with a few or many accompanying photographs. Photo essays can be sequential in nature, intended to be viewed in a particular order—or they may consist of non-ordered photographs viewed all at once or in an order that the viewer chooses. All photo essays are collections of photographs, but not all collections of photographs are photo essays. Photo essays often address a certain issue or attempt to capture the character of places and events.

Visual arts

In the visual arts, an essay is a preliminary drawing or sketch that forms a basis for a final painting or sculpture, made as a test of the work's composition (this meaning of the term, like several of those following, comes from the word essay's meaning of "attempt" or "trial").