Synergy is an interaction or cooperation giving rise to a

whole that is greater than the simple sum of its parts (i.e., a

non-linear addition of force, energy, or effect). The term synergy comes from the Attic Greek word συνεργία synergia from synergos, συνεργός, meaning "working together". Synergy is similar in concept to emergence.

History

The words synergy and synergetic have been used in the field of physiology since at least the middle of the 19th century:

SYN'ERGY, Synergi'a, Synenergi'a, (F.) Synergie; from συν, 'with', and εργον, 'work'. A correlation or concourse of action between different organs in health; and, according to some, in disease.

- —Dunglison, Robley Medical Lexicon Blanchard and Lea, 1853

In 1896, Henri Mazel applied the term "synergy" to social psychology by writing La synergie sociale,

in which he argued that Darwinian theory failed to account of "social

synergy" or "social love", a collective evolutionary drive. The highest

civilizations were the work not only of the elite but of the masses too;

those masses must be led, however, because the crowd, a feminine and

unconscious force, cannot distinguish between good and evil.

In 1909, Lester Frank Ward defined synergy as the universal constructive principle of nature:

I have characterized the social struggle as centrifugal and social

solidarity as centripetal. Either alone is productive of evil

consequences. Struggle is essentially destructive of the social order,

while communism removes individual initiative. The one leads to

disorder, the other to degeneracy. What is not seen—the truth that has

no expounders—is that the wholesome, constructive movement consists in

the properly ordered combination and interaction of both these

principles. This is social synergy, which is a form of cosmic synergy, the universal constructive principle of nature.

- —Ward, Lester F. Glimpses of the Cosmos, volume VI (1897–1912) G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1918, p. 358

In Christian theology, synergism is the idea that salvation involves some form of cooperation between divine grace and human freedom.

A modern view of synergy in natural sciences derives from the relationship between energy and information. Synergy is manifested when the system makes the transition between the different information (i.e. order, complexity) embedded in both systems.

Abraham Maslow and John Honigmann drew attention to an important development in the cultural anthropology field which arose in lectures by Ruth Benedict

from 1941, for which the original manuscripts have been lost but the

ideas preserved in "Synergy: Some Notes of Ruth Benedict" (1969).

Descriptions and usages

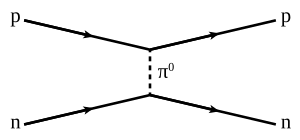

In the natural world, synergistic phenomena are ubiquitous, ranging from physics (for example, the different combinations of quarks that produce protons and neutrons)

to chemistry (a popular example is water, a compound of hydrogen and

oxygen), to the cooperative interactions among the genes in genomes, the division of labor in bacterial colonies, the synergies of scale in multicellular organisms, as well as the many different kinds of synergies produced by socially-organized groups, from honeybee colonies to wolf packs and human societies: compare stigmergy, a mechanism of indirect coordination between agents or actions that results in the self-assembly of complex systems.

Even the tools and technologies that are widespread in the natural

world represent important sources of synergistic effects. The tools that

enabled early hominins to become systematic big-game hunters is a primordial human example.

In the context of organizational behavior,

following the view that a cohesive group is more than the sum of its

parts, synergy is the ability of a group to outperform even its best

individual member. These conclusions are derived from the studies

conducted by Jay Hall on a number of laboratory-based group ranking and

prediction tasks. He found that effective groups actively looked for the

points in which they disagreed and in consequence encouraged conflicts

amongst the participants in the early stages of the discussion. In

contrast, the ineffective groups felt a need to establish a common view

quickly, used simple decision making methods such as averaging, and

focused on completing the task rather than on finding solutions they

could agree on.

In a technical context, its meaning is a construct or collection of

different elements working together to produce results not obtainable by

any of the elements alone. The elements, or parts, can include people,

hardware, software, facilities, policies, documents: all things required

to produce system-level results. The value added by the system as a

whole, beyond that contributed independently by the parts, is created

primarily by the relationship among the parts, that is, how they are

interconnected. In essence, a system constitutes a set of interrelated

components working together with a common objective: fulfilling some

designated need.

If used in a business application, synergy means that teamwork

will produce an overall better result than if each person within the

group were working toward the same goal individually. However, the

concept of group cohesion

needs to be considered. Group cohesion is that property that is

inferred from the number and strength of mutual positive attitudes among

members of the group. As the group becomes more cohesive, its

functioning is affected in a number of ways. First, the interactions and

communication between members increase. Common goals, interests and

small size all contribute to this. In addition, group member

satisfaction increases as the group provides friendship and support

against outside threats.

There are negative aspects of group cohesion that have an effect

on group decision-making and hence on group effectiveness. There are two

issues arising. The risky shift

phenomenon is the tendency of a group to make decisions that are

riskier than those that the group would have recommended individually.

Group Polarisation

is when individuals in a group begin by taking a moderate stance on an

issue regarding a common value and, after having discussed it, end up

taking a more extreme stance.

A second, potential negative consequence of group cohesion is

group think. Group think is a mode of thinking that people engage in

when they are deeply involved in cohesive group, when the members'

striving for unanimity overrides their motivation to appraise

realistically the alternative courses of action. Studying the events of

several American policy "disasters" such as the failure to anticipate

the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (1941) and the Bay of Pigs Invasion

fiasco (1961), Irving Janis argued that they were due to the cohesive

nature of the committees that made the relevant decisions.

That decisions made by committees lead to failure in a simple system is noted by Dr. Chris Elliot. His case study looked at IEEE-488,

an international standard set by the leading US standards body; it led

to a failure of small automation systems using the IEEE-488 standard

(which codified a proprietary communications standard HP-IB).

But the external devices used for communication were made by two

different companies, and the incompatibility between the external

devices led to a financial loss for the company. He argues that systems

will be safe only if they are designed, not if they emerge by chance.

The idea of a systemic approach is endorsed by the United Kingdom Health and Safety Executive.

The successful performance of the health and safety management depends

upon the analyzing the causes of incidents and accidents and learning

correct lessons from them. The idea is that all events (not just those

causing injuries) represent failures in control, and present an

opportunity for learning and improvement. UK Health and Safety Executive, Successful health and safety management

(1997): this book describes the principles and management practices,

which provide the basis of effective health and safety management. It

sets out the issues that need to be addressed, and can be used for

developing improvement programs, self-audit, or self-assessment. Its

message is that organizations must manage health and safety with the

same degree of expertise and to the same standards as other core

business activities, if they are to effectively control risks and

prevent harm to people.

The term synergy was refined by R. Buckminster Fuller, who analyzed some of its implications more fully and coined the term synergetics.

- A dynamic state in which combined action is favored over the difference of individual component actions.

- Behavior of whole systems unpredicted by the behavior of their parts taken separately, known as emergent behavior.

- The cooperative action of two or more stimuli (or drugs), resulting

in a different or greater response than that of the individual stimuli.

Mathematical formalizations of synergy have been proposed using information theory to rigorously define the relationships between "wholes" and "parts".

In this context, synergy is said to occur when there is information

present in the joint state of multiple variables that cannot be

extracted from the individual parts considered individually. For

example, consider the logical XOR gate. If  for three binary variables, the mutual information between any individual source and the target is 0 bit. However, the joint mutual information

for three binary variables, the mutual information between any individual source and the target is 0 bit. However, the joint mutual information  bit. There is information about the target that can only be extracted

from the joint state of the inputs considered jointly, and not any

others.

bit. There is information about the target that can only be extracted

from the joint state of the inputs considered jointly, and not any

others.

There is, thus far, no universal agreement on how synergy can

best be quantified, with different approaches that decompose information

into redundant, unique, and synergistic components appearing in the

literature.

Despite the lack of universal agreement, information-theoretic

approaches to statistical synergy have been applied to diverse fields,

including climatology, neuroscience sociology, and machine learning Synergy has also been proposed as a possible foundation on which to build a mathematically robust definition of emergence in complex systems and may be relevant to formal theories of consciousness.

Biological sciences

Synergy of various kinds has been advanced by Peter Corning

as a causal agency that can explain the progressive evolution of

complexity in living systems over the course of time. According to the

Synergism Hypothesis, synergistic effects have been the drivers of

cooperative relationships of all kinds and at all levels in living

systems. The thesis, in a nutshell, is that synergistic effects have

often provided functional advantages (economic benefits) in relation to

survival and reproduction that have been favored by natural selection.

The cooperating parts, elements, or individuals become, in effect,

functional "units" of selection in evolutionary change.

Similarly, environmental systems may react in a non-linear way to

perturbations, such as climate change, so that the outcome may be

greater than the sum of the individual component alterations.

Synergistic responses are a complicating factor in environmental

modeling.

Pest synergy

Pest synergy would occur in a biological host organism population, where, for example, the introduction of parasite

A may cause 10% fatalities, and parasite B may also cause 10% loss.

When both parasites are present, the losses would normally be expected

to total less than 20%, yet, in some cases, losses are significantly

greater. In such cases, it is said that the parasites in combination

have a synergistic effect.

Drug synergy

Mechanisms that may be involved in the development of synergistic effects include:

- Effect on the same cellular system (e.g. two different antibiotics like a penicillin and an aminoglycoside; penicillins damage the cell wall of gram-positive bacteria and improve the penetration of aminoglycosides).

- Bioavailability (e.g. ayahuasca (or pharmahuasca) consists of DMT combined with MAOIs that interfere with the action of the MAO enzyme and stop the breakdown of chemical compounds such as DMT).

- Reduced risk for substance abuse (e.g. lisdexamfetamine, which is a combination of the amino acid L-lysine, attached to dextroamphetamine, may have a lower liability for abuse as a recreational drug)

- Increased potency (e.g. as with other NSAIDs, combinations of aspirin and caffeine provide slightly greater pain relief than aspirin alone).

- Prevention or delay of degradation in the body (e.g. the antibiotic Ciprofloxacin inhibits the metabolism of Theophylline).[30]: 931

- Slowdown of excretion (e.g. Probenecid delays the renal excretion of Penicillin and thus prolongs its effect).

- Anticounteractive action: for example, the effect of oxaliplatin and irinotecan. Oxaliplatin intercalates DNA, thereby preventing the cell from replicating DNA. Irinotecan inhibits topoisomerase 1, consequently the cytostatic effect is increased.

- Effect on the same receptor but different sites (e.g. the

coadministration of benzodiazepines and barbiturates, both act by

enhancing the action of GABA on GABAA receptors, but

benzodiazepines increase the frequency of channel opening, whilst

barbiturates increase the channel closing time, making these two drugs

dramatically enhance GABAergic neurotransmission).

- In addition to the chemical nature of the drug itself, the topology

of the chemical reaction network that connect the two targets determines

the type of drug-drug interaction.

More mechanisms are described in an exhaustive 2009 review.

Toxicological synergy

Toxicological

synergy is of concern to the public and regulatory agencies because

chemicals individually considered safe might pose unacceptable health or

ecological risk in combination. Articles in scientific and lay journals

include many definitions of chemical or toxicological synergy, often

vague or in conflict with each other. Because toxic interactions are

defined relative to the expectation under "no interaction", a

determination of synergy (or antagonism) depends on what is meant by "no

interaction". The United States Environmental Protection Agency has one of the more detailed and precise definitions of toxic interaction, designed to facilitate risk assessment.

In their guidance documents, the no-interaction default assumption is

dose addition, so synergy means a mixture response that exceeds that

predicted from dose addition. The EPA emphasizes that synergy does not

always make a mixture dangerous, nor does antagonism always make the

mixture safe; each depends on the predicted risk under dose addition.

For example, a consequence of pesticide use is the risk of health effects. During the registration of pesticides in the United States

exhaustive tests are performed to discern health effects on humans at

various exposure levels. A regulatory upper limit of presence in foods

is then placed on this pesticide. As long as residues in the food stay

below this regulatory level, health effects are deemed highly unlikely

and the food is considered safe to consume.

However, in normal agricultural practice, it is rare to use only a

single pesticide. During the production of a crop, several different

materials may be used. Each of them has had determined a regulatory

level at which they would be considered individually safe. In many

cases, a commercial pesticide is itself a combination of several

chemical agents, and thus the safe levels actually represent levels of

the mixture. In contrast, a combination created by the end user, such as

a farmer, has rarely been tested in that combination. The potential for

synergy is then unknown or estimated from data on similar combinations.

This lack of information also applies to many of the chemical

combinations to which humans are exposed, including residues in food,

indoor air contaminants, and occupational exposures to chemicals. Some

groups think that the rising rates of cancer, asthma, and other health

problems may be caused by these combination exposures; others have

alternative explanations. This question will likely be answered only

after years of exposure by the population in general and research on

chemical toxicity, usually performed on animals. Examples of pesticide

synergists include Piperonyl butoxide and MGK 264.

Human synergy

Synergy

exists in individual and social interactions among humans, with some

arguing that social cooperation cannot be requires synergy to continue.

One way of quantifying synergy in human social groups is via energy

use, where larger groups of humans (i.e., cities) use energy more

efficiently that smaller groups of humans.

Human synergy can also occur on a smaller scale, like when

individuals huddle together for warmth or in workplaces where labor

specialization increase efficiencies.

When synergy occurs in the work place, the individuals involved

get to work in a positive and supportive working environment. When

individuals get to work in environments such as these, the company reaps

the benefits. The authors of Creating the Best Workplace on Earth

Rob Goffee and Gareth Jones, state that "highly engaged employees are,

on average, 50% more likely to exceed expectations that the

least-engaged workers. And companies with highly engaged people

outperform firms with the most disengaged folks- by 54% in employee retention, by 89% in customer satisfaction, and by fourfold in revenue growth.

Also, those that are able to be open about their views on the company,

and have confidence that they will be heard, are likely to be a more

organized employee who helps his/ her fellow team members succeed.

Human interaction with technology can also increase synergy. Organismic computing is an approach to improving group efficacy by increasing synergy in human groups via technological means.

Theological synergism

In Christian theology, synergism is the belief that salvation involves a cooperation between divine grace and human freedom. Eastern Orthodox

theology, in particular, uses the term "synergy" to describe this

relationship, drawing on biblical language: "in Paul's words, 'We are

fellow-workers (synergoi) with God' (1 Corinthians iii, 9)".

Corporate synergy

Corporate synergy

occurs when corporations interact congruently. A corporate synergy

refers to a financial benefit that a corporation expects to realize when

it merges with or acquires

another corporation. This type of synergy is a nearly ubiquitous

feature of a corporate acquisition and is a negotiating point between

the buyer and seller that impacts the final price both parties agree to.

There are distinct types of corporate synergies, as follows.

Marketing

A marketing synergy refers to the use of information campaigns, studies, and scientific discovery or experimentation for research and development. This promotes the sale of products for varied use or off-market sales as well as development of marketing tools and in several cases exaggeration of effects. It is also often a meaningless buzzword used by corporate leaders.

Microsoft Word offers "cooperation" as a refinement suggestion to the word "synergy."

Revenue

A revenue

synergy refers to the opportunity of a combined corporate entity to

generate more revenue than its two predecessor stand-alone companies

would be able to generate. For example, if company A sells product X

through its sales force, company B sells product Y, and company A

decides to buy company B, then the new company could use each

salesperson to sell products X and Y, thereby increasing the revenue

that each salesperson generates for the company.

In media revenue, synergy is the promotion and sale of a product throughout the various subsidiaries of a media conglomerate, e.g. films, soundtracks, or video games.

Financial

Financial

synergy gained by the combined firm is a result of number of benefits

which flow to the entity as a consequence of acquisition and merger.

These benefits may be:

Cash slack

This

is when a firm having a number of cash extensive projects acquires a

firm which is cash-rich, thus enabling the new combined firm to enjoy

the profits from investing the cash of one firm in the projects of the

other.

Debt capacity

If two firms have no or little capacity to carry debt

before individually, it is possible for them to join and gain the

capacity to carry the debt through decreased gearing (leverage). This

creates value for the firm, as debt is thought to be a cheaper source of

finance.

Tax benefits

It is possible for one firm to have unused tax benefits

which might be offset against the profits of another after combination,

thus resulting in less tax being paid. However this greatly depends on

the tax law of the country.

Management

Synergy in management and in relation to teamwork refers to the combined effort of individuals as participants of the team.

The condition that exists when the organization's parts interact to

produce a joint effect that is greater than the sum of the parts acting

alone. Positive or negative synergies can exist. In these cases,

positive synergy has positive effects such as improved efficiency in

operations, greater exploitation of opportunities, and improved

utilization of resources. Negative synergy on the other hand has

negative effects such as: reduced efficiency of operations, decrease in

quality, underutilization of resources and disequilibrium with the

external environment.

Cost

A

cost synergy refers to the opportunity of a combined corporate entity to

reduce or eliminate expenses associated with running a business. Cost

synergies are realized by eliminating positions that are viewed as

duplicate within the merged entity.

Examples include the headquarters office of one of the predecessor

companies, certain executives, the human resources department, or other

employees of the predecessor companies. This is related to the economic

concept of economies of scale.

Synergistic action in economy

The

synergistic action of the economic players lies within the economic

phenomenon's profundity. The synergistic action gives different

dimensions to competitiveness, strategy and network identity becoming an

unconventional "weapon" which belongs to those who exploit the economic

systems' potential in depth.

Synergistic determinants

The

synergistic gravity equation (SYNGEq), according to its complex

"title", represents a synthesis of the endogenous and exogenous factors

which determine the private and non-private economic decision makers to

call to actions of synergistic exploitation of the economic network in

which they operate. That is to say, SYNGEq constitutes a big picture of

the factors/motivations which determine the entrepreneurs to contour an

active synergistic network. SYNGEq includes both factors which character

is changing over time (such as the competitive conditions), as well as

classics factors, such as the imperative of the access to resources of

the collaboration and the quick answers. The synergistic gravity

equation (SINGEq) comes to be represented by the formula:

ΣSYN.Act = ΣR-*I(CRed+COOP++AUnimit.)*V(Cust.+Info.)*cc

where:

- ΣSYN.Act = the sum of the synergistic actions adopted (by the economic actor)

- Σ R- = the amount of unpurchased but necessary resources

- ICRed = the imperative for cost reductions

- ICOOP+ = the imperative for deep cooperation (functional interdependence)

- IAUnimit. = the imperative for purchasing unimitable competitive advantages (for the economic actor)

- VCust = the necessity of customer value in purchasing future profits

and competitive advantages VInfo = the necessity of informational value

in purchasing future profits and competitive advantages

- cc = the specific competitive conditions in which the economic actor operates

Synergistic networks and systems

The

synergistic network represents an integrated part of the economic

system which, through the coordination and control functions (of the

undertaken economic actions), agrees synergies. The networks which

promote synergistic actions can be divided in horizontal synergistic

networks and vertical synergistic networks.

Synergy effects

The

synergy effects are difficult (even impossible) to imitate by

competitors and difficult to reproduce by their authors because these

effects depend on the combination of factors with time-varying

characteristics. The synergy effects are often called "synergistic

benefits", representing the direct and implied result of the

developed/adopted synergistic actions.

Computers

Synergy can also be defined as the combination of human strengths and computer strengths, such as advanced chess. Computers can process data much more quickly than humans, but lack the ability to respond meaningfully to arbitrary stimuli.

Synergy in literature

Etymologically,

the "synergy" term was first used around 1600, deriving from the Greek

word "synergos", which means "to work together" or "to cooperate". If

during this period the synergy concept was mainly used in the

theological field (describing "the cooperation of human effort with

divine will"), in the 19th and 20th centuries, "synergy" was promoted in

physics and biochemistry, being implemented in the study of the open

economic systems only in the 1960 and 1970s.

In 1938, J. R. R. Tolkien wrote an essay titled On Fairy Stores, delivered at an Andrew Lang Lecture, and reprinted in his book, The Tolkien Reader, published in 1966. In it, he made two references to synergy, although he did not use that term. He wrote:

Faerie cannot be caught in a net of words; for it is one of its

qualities to be indescribable, though not imperceptible. It has many

ingredients, but analysis will not necessarily discover the secret of

the whole.

And more succinctly, in a footnote, about the "part of producing the web of an intricate story", he wrote:

It is indeed easier to unravel a single thread — an incident, a name, a motive — than to trace the history of any picture

defined by many threads. For with the picture in the tapestry a new

element has come in: the picture is greater than, and not explained by,

the sum of the component threads.

The book "Synergy"

Synergy, a book: DION, Eric (2017), Synergy; A Theoretical Model of Canada's Comprehensive Approach, iUniverse, 308 pp.

The

informational synergies which can be applied also in media involve a

compression of transmission, access and use of information's time, the

flows, circuits and means of handling information being based on a

complementary, integrated, transparent and coordinated use of knowledge.

In media economics, synergy is the promotion and sale of a

product (and all its versions) throughout the various subsidiaries of a

media conglomerate, e.g. films, soundtracks or video games. Walt Disney pioneered synergistic marketing techniques in the 1930s by granting dozens of firms the right to use his Mickey Mouse

character in products and ads, and continued to market Disney media

through licensing arrangements. These products can help advertise the

film itself and thus help to increase the film's sales. For example, the

Spider-Man films had toys of webshooters and figures of the characters made, as well as posters and games. The NBC sitcom 30 Rock often shows the power of synergy, while also poking fun at the use of the term in the corporate world. There are also different forms of synergy in popular card games like Magic: The Gathering, Yu-Gi-Oh!, Cardfight!! Vanguard, and Future Card Buddyfight.

![{\displaystyle {\mathcal {L}}_{\mathrm {C} }=-{\frac {g}{\ {\sqrt {2\;}}\ }}\ \left[\ {\overline {u}}_{i}\ \gamma ^{\mu }\ {\frac {\ 1-\gamma ^{5}\ }{2}}\;M_{ij}^{\mathrm {CKM} }\ d_{j}+{\overline {\nu }}_{i}\ \gamma ^{\mu }\;{\frac {\ 1-\gamma ^{5}\ }{2}}\;e_{i}\ \right]\ W_{\mu }^{+}+\mathrm {h.c.} ~,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a58fb2388e4f81affcfbb2f9137be3fc21c01d32)

![{\displaystyle {\mathcal {L}}_{\mathrm {WWV} }=-i\ g\ \left[\;\left(\ W_{\mu \nu }^{+}\ W^{-\mu }-W^{+\mu }\ W_{\mu \nu }^{-}\ \right)\left(\ A^{\nu }\ \sin \theta _{\mathrm {W} }-Z^{\nu }\ \cos \theta _{\mathrm {W} }\ \right)+W_{\nu }^{-}\ W_{\mu }^{+}\ \left(\ A^{\mu \nu }\ \sin \theta _{\mathrm {W} }-Z^{\mu \nu }\ \cos \theta _{\mathrm {W} }\ \right)\;\right]~.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3a692b930d152ed1c16bd24ebede10eb0a7f7c2b)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\mathcal {L}}_{\mathrm {WWVV} }=-{\frac {\ g^{2}\ }{4}}\ {\Biggl \{}\ &{\Bigl [}\ 2\ W_{\mu }^{+}\ W^{-\mu }+(\ A_{\mu }\ \sin \theta _{\mathrm {W} }-Z_{\mu }\ \cos \theta _{\mathrm {W} }\ )^{2}\ {\Bigr ]}^{2}\\&-{\Bigl [}\ W_{\mu }^{+}\ W_{\nu }^{-}+W_{\nu }^{+}\ W_{\mu }^{-}+\left(\ A_{\mu }\ \sin \theta _{\mathrm {W} }-Z_{\mu }\ \cos \theta _{\mathrm {W} }\ \right)\left(\ A_{\nu }\ \sin \theta _{\mathrm {W} }-Z_{\nu }\ \cos \theta _{\mathrm {W} }\ \right)\ {\Bigr ]}^{2}\,{\Biggr \}}~.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1b7a413ef9a695a06d5c93067c2745e6bfe3d1a3)