A space elevator, also referred to as a space bridge, star ladder, and orbital lift, is a proposed type of planet-to-space transportation system, often depicted in science fiction. The main component would be a cable (also called a tether) anchored to the surface and extending into space. An Earth-based space elevator would consist of a cable with one end attached to the surface near the equator and the other end attached to a counterweight in space beyond geostationary orbit (35,786 km altitude). The competing forces of gravity, which is stronger at the lower end, and the upward centrifugal force, which is stronger at the upper end, would result in the cable being held up, under tension, and stationary over a single position on Earth. With the tether deployed, climbers (crawlers) could repeatedly climb up and down the tether by mechanical means, releasing their cargo to and from orbit. The design would permit vehicles to travel directly between a planetary surface, such as the Earth's, and orbit, without the use of large rockets.

History

Early concept

The idea of the space elevator appears to have developed independently in different times and places. The earliest models originated with two Russian scientists in the late nineteenth century. In his 1895 collection Dreams of Earth and Sky, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky envisioned a massive sky ladder to reach the stars as a way to overcome gravity. Decades later, in 1960, Yuri Artsutanov independently developed the concept of a "Cosmic Railway", a space elevator tethered from an orbiting satellite to an anchor on the equator, aiming to provide a safer and more efficient alternative to rockets. In 1966, Isaacs and his colleagues introduced the concept of the 'Sky-Hook', proposing a satellite in geostationary orbit with a cable extending to Earth.

Innovations and designs

The space elevator concept reached America in 1975 when Jerome Pearson began researching the idea, inspired by Arthur C. Clarke's 1969 speech before Congress. After working as an engineer for NASA and the Air Force Research Laboratory, he developed a design for an "Orbital Tower", intended to harness Earth's rotational energy to transport supplies into low Earth orbit. In his publication in Acta Astronautica, the cable would be thickest at geostationary orbit where tension is greatest, and narrowest at the tips to minimize weight per unit area. He proposed extending a counterweight to 144,000 kilometers (89,000 miles) as without a large counterweight, the upper cable would need to be longer due to the way gravitational and centrifugal forces change with distance from Earth. His analysis included the Moon's gravity, wind, and moving payloads. Building the elevator would have required thousands of Space Shuttle trips, though material could be transported once a minimum strength strand reached the ground or be manufactured in space from asteroidal or lunar ore. Pearson's findings, published in Acta Astronautica, caught Clarke's attention and led to technical consultations for Clarke's science fiction novel The Fountains of Paradise (1979), which features a space elevator.

The first gathering of multiple experts who wanted to investigate this alternative to space flight took place at the 1999 NASA conference 'Advanced Space Infrastructure Workshop on Geostationary Orbiting Tether Space Elevator Concepts'. in Huntsville, Alabama. D.V. Smitherman, Jr., published the findings in August of 2000 under the title Space Elevators: An Advanced Earth-Space Infrastructure for the New Millennium, concluding that the space elevator could not be built for at least another 50 years due to concerns about the cable's material, deployment, and upkeep.

Dr. B.C. Edwards suggested that a 100,000 km (62,000 mi) long paper-thin ribbon, utilizing a carbon nanotube composite material could solve the tether issue due to their high tensile strength and low weight The proposed wide-thin ribbon-like cross-section shape instead of earlier circular cross-section concepts would increase survivability against meteoroid impacts. With support from NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts (NIAC), his work was involved more than 20 institutions and 50 participants. The Space Elevator NIAC Phase II Final Report, in combination with the book The Space Elevator: A Revolutionary Earth-to-Space Transportation System (Edwards and Westling, 2003) summarized all effort to design a space elevator including deployment scenario, climber design, power delivery system, orbital debris avoidance, anchor system, surviving atomic oxygen, avoiding lightning and hurricanes by locating the anchor in the western equatorial Pacific, construction costs, construction schedule, and environmental hazards. Additionally, he researched the structural integrity and load-bearing capabilities of space elevator cables, emphasizing their need for high tensile strength and resilience. His space elevator concept never reached NIAC's third phase, which he attributed to submitting his final proposal during the week of the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster.

21st century advancements

To speed space elevator development, proponents have organized several competitions, similar to the Ansari X Prize, for relevant technologies. Among them are Elevator:2010, which organized annual competitions for climbers, ribbons and power-beaming systems from 2005 to 2009, the Robogames Space Elevator Ribbon Climbing competition, as well as NASA's Centennial Challenges program, which, in March 2005, announced a partnership with the Spaceward Foundation (the operator of Elevator:2010), raising the total value of prizes to US$400,000. The first European Space Elevator Challenge (EuSEC) to establish a climber structure took place in August 2011.

In 2005, "the LiftPort Group of space elevator companies announced that it will be building a carbon nanotube manufacturing plant in Millville, New Jersey, to supply various glass, plastic and metal companies with these strong materials. Although LiftPort hopes to eventually use carbon nanotubes in the construction of a 100,000 km (62,000 mi) space elevator, this move will allow it to make money in the short term and conduct research and development into new production methods." Their announced goal was a space elevator launch in 2010. On 13 February 2006, the LiftPort Group announced that, earlier the same month, they had tested a mile of "space-elevator tether" made of carbon-fiber composite strings and fiberglass tape measuring 5 cm (2.0 in) wide and 1 mm (0.039 in) (approx. 13 sheets of paper) thick, lifted with balloons. In April 2019, Liftport CEO Michael Laine admitted little progress has been made on the company's lofty space elevator ambitions, even after receiving more than $200,000 in seed funding. The carbon nanotube manufacturing facility that Liftport announced in 2005 was never built.

In 2007, Elevator:2010 held the 2007 Space Elevator games, which featured US$500,000 awards for each of the two competitions ($1,000,000 total), as well as an additional $4,000,000 to be awarded over the next five years for space elevator related technologies. No teams won the competition, but a team from MIT entered the first 2-gram (0.07 oz), 100-percent carbon nanotube entry into the competition. Japan held an international conference in November 2008 to draw up a timetable for building the elevator.

In 2012, the Obayashi Corporation announced that it could build a space elevator by 2050 using carbon nanotube technology. The design's passenger climber would be able to reach the GEO level after an 8-day trip. Further details were published in 2016.

In 2013, the International Academy of Astronautics published a technological feasibility assessment which concluded that the critical capability improvement needed was the tether material, which was projected to achieve the necessary specific strength within 20 years. The four-year long study looked into many facets of space elevator development including missions, development schedules, financial investments, revenue flow, and benefits. It was reported that it would be possible to operationally survive smaller impacts and avoid larger impacts, with meteors and space debris, and that the estimated cost of lifting a kilogram of payload to GEO and beyond would be $500.

In 2014, Google X's Rapid Evaluation R&D team began the design of a Space Elevator, eventually finding that no one had yet manufactured a perfectly formed carbon nanotube strand longer than a meter. They thus put the project in "deep freeze" and also keep tabs on any advances in the carbon nanotube field.

In 2018, researchers at Japan's Shizuoka University launched STARS-Me, two CubeSats connected by a tether, which a mini-elevator will travel on. The experiment was launched as a test bed for a larger structure.

In 2019, the International Academy of Astronautics published "Road to the Space Elevator Era", a study report summarizing the assessment of the space elevator as of summer 2018. The essence is that a broad group of space professionals gathered and assessed the status of the space elevator development, each contributing their expertise and coming to similar conclusions: (a) Earth Space Elevators seem feasible, reinforcing the IAA 2013 study conclusion (b) Space Elevator development initiation is nearer than most think. This last conclusion is based on a potential process for manufacturing macro-scale single crystal graphene with higher specific strength than carbon nanotubes.

Materials

A significant difficulty with making a space elevator for the Earth is strength of materials. Since the structure must hold up its own weight in addition to the payload it may carry, the strength to weight ratio, or Specific strength, of the material it is made of must be extremely high.

Since 1959, most ideas for space elevators have focused on purely tensile structures, with the weight of the system held up from above by centrifugal forces. In the tensile concepts, a space tether reaches from a large mass (the counterweight) beyond geostationary orbit to the ground. This structure is held in tension between Earth and the counterweight like an upside-down plumb bob. The cable thickness is tapered based on tension; it has its maximum at a geostationary orbit and the minimum on the ground.

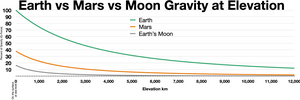

The concept is applicable to other planets and celestial bodies. For locations in the Solar System with weaker gravity than Earth's (such as the Moon or Mars), the strength-to-density requirements for tether materials are not as problematic. Currently available materials (such as Kevlar) are strong and light enough that they could be practical as the tether material for elevators there.

Available materials are not strong and light enough to make an Earth space elevator practical. Some sources expect that future advances in carbon nanotubes (CNTs) could lead to a practical design. Other sources believe that CNTs will never be strong enough. Possible future alternatives include boron nitride nanotubes, diamond nanothreads and macro-scale single crystal graphene.

In fiction

In 1979, space elevators were introduced to a broader audience with the simultaneous publication of Arthur C. Clarke's novel, The Fountains of Paradise, in which engineers construct a space elevator on top of a mountain peak in the fictional island country of "Taprobane" (loosely based on Sri Lanka, albeit moved south to the Equator), and Charles Sheffield's first novel, The Web Between the Worlds, also featuring the building of a space elevator. Three years later, in Robert A. Heinlein's 1982 novel Friday, the principal character mentions a disaster at the “Quito Sky Hook” and makes use of the "Nairobi Beanstalk" in the course of her travels. In Kim Stanley Robinson's 1993 novel Red Mars, colonists build a space elevator on Mars that allows both for more colonists to arrive and also for natural resources mined there to be able to leave for Earth. Larry Niven's book Rainbow Mars describes a space elevator built on Mars. In David Gerrold's 2000 novel, Jumping Off The Planet, a family excursion up the Ecuador "beanstalk" is actually a child-custody kidnapping. Gerrold's book also examines some of the industrial applications of a mature elevator technology. The concept of a space elevator, called the Beanstalk, is also depicted in John Scalzi's 2005 novel Old Man's War. In a biological version, Joan Slonczewski's 2011 novel The Highest Frontier depicts a college student ascending a space elevator constructed of self-healing cables of anthrax bacilli. The engineered bacteria can regrow the cables when severed by space debris.

Physics

Apparent gravitational field

An Earth space elevator cable rotates along with the rotation of the Earth. Therefore, the cable, and objects attached to it, would experience upward centrifugal force in the direction opposing the downward gravitational force. The higher up the cable the object is located, the less the gravitational pull of the Earth, and the stronger the upward centrifugal force due to the rotation, so that more centrifugal force opposes less gravity. The centrifugal force and the gravity are balanced at geosynchronous equatorial orbit (GEO). Above GEO, the centrifugal force is stronger than gravity, causing objects attached to the cable there to pull upward on it. Because the counterweight, above GEO, is rotating about the Earth faster than the natural orbital speed for that altitude, it exerts a centrifugal pull on the cable and thus holds the whole system aloft.

The net force for objects attached to the cable is called the apparent gravitational field. The apparent gravitational field for attached objects is the (downward) gravity minus the (upward) centrifugal force. The apparent gravity experienced by an object on the cable is zero at GEO, downward below GEO, and upward above GEO.

The apparent gravitational field can be represented this way:

where

At some point up the cable, the two terms (downward gravity and upward centrifugal force) are equal and opposite. Objects fixed to the cable at that point put no weight on the cable. This altitude (r1) depends on the mass of the planet and its rotation rate. Setting actual gravity equal to centrifugal acceleration gives:

This is 35,786 km (22,236 mi) above Earth's surface, the altitude of geostationary orbit.

On the cable below geostationary orbit, downward gravity would be greater than the upward centrifugal force, so the apparent gravity would pull objects attached to the cable downward. Any object released from the cable below that level would initially accelerate downward along the cable. Then gradually it would deflect eastward from the cable. On the cable above the level of stationary orbit, upward centrifugal force would be greater than downward gravity, so the apparent gravity would pull objects attached to the cable upward. Any object released from the cable above the geosynchronous level would initially accelerate upward along the cable. Then gradually it would deflect westward from the cable.

Cable section

Historically, the main technical problem has been considered the ability of the cable to hold up, with tension, the weight of itself below any given point. The greatest tension on a space elevator cable is at the point of geostationary orbit, 35,786 km (22,236 mi) above the Earth's equator. This means that the cable material, combined with its design, must be strong enough to hold up its own weight from the surface up to 35,786 km (22,236 mi). A cable which is thicker in cross section area at that height than at the surface could better hold up its own weight over a longer length. How the cross section area tapers from the maximum at 35,786 km (22,236 mi) to the minimum at the surface is therefore an important design factor for a space elevator cable.

To maximize the usable excess strength for a given amount of cable material, the cable's cross section area would need to be designed for the most part in such a way that the stress (i.e., the tension per unit of cross sectional area) is constant along the length of the cable. The constant-stress criterion is a starting point in the design of the cable cross section area as it changes with altitude. Other factors considered in more detailed designs include thickening at altitudes where more space junk is present, consideration of the point stresses imposed by climbers, and the use of varied materials. To account for these and other factors, modern detailed designs seek to achieve the largest safety margin possible, with as little variation over altitude and time as possible. In simple starting-point designs, that equates to constant-stress.

For a constant-stress cable with no safety margin, the cross-section-area as a function of distance from Earth's center is given by the following equation:

where

Safety margin can be accounted for by dividing T by the desired safety factor.

Cable materials

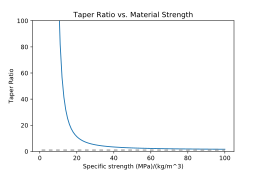

Using the above formula, the ratio between the cross-section at geostationary orbit and the cross-section at Earth's surface, known as taper ratio, can be calculated:

| Material | Tensile strength (MPa) |

Density (kg/m3) |

Specific strength (MPa)/(kg/m3) |

Taper ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steel | 5,000 | 7,900 | 0.63 | 1.6×1033 |

| Kevlar | 3,600 | 1,440 | 2.5 | 2.5×108 |

| UHMWPE @23°C | 3,600 | 0,980 | 3.7 | 5.4×106 |

| Single wall carbon nanotube | 130,000 | 1,300 | 100 | 1.6 |

The taper ratio becomes very large unless the specific strength of the material used approaches 48 (MPa)/(kg/m3). Low specific strength materials require very large taper ratios which equates to large (or astronomical) total mass of the cable with associated large or impossible costs.

Structure

There are a variety of space elevator designs proposed for many planetary bodies. Almost every design includes a base station, a cable, climbers, and a counterweight. For an Earth Space Elevator the Earth's rotation creates upward centrifugal force on the counterweight. The counterweight is held down by the cable while the cable is held up and taut by the counterweight. The base station anchors the whole system to the surface of the Earth. Climbers climb up and down the cable with cargo.

Base station

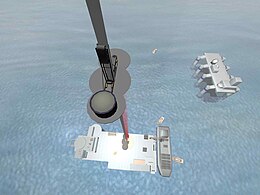

Modern concepts for the base station/anchor are typically mobile stations, large oceangoing vessels or other mobile platforms. Mobile base stations would have the advantage over the earlier stationary concepts (with land-based anchors) by being able to maneuver to avoid high winds, storms, and space debris. Oceanic anchor points are also typically in international waters, simplifying and reducing the cost of negotiating territory use for the base station.

Stationary land-based platforms would have simpler and less costly logistical access to the base. They also would have the advantage of being able to be at high altitudes, such as on top of mountains. In an alternate concept, the base station could be a tower, forming a space elevator which comprises both a compression tower close to the surface, and a tether structure at higher altitudes. Combining a compression structure with a tension structure would reduce loads from the atmosphere at the Earth end of the tether, and reduce the distance into the Earth's gravity field that the cable needs to extend, and thus reduce the critical strength-to-density requirements for the cable material, all other design factors being equal.

Cable

A space elevator cable would need to carry its own weight as well as the additional weight of climbers. The required strength of the cable would vary along its length. This is because at various points it would have to carry the weight of the cable below, or provide a downward force to retain the cable and counterweight above. Maximum tension on a space elevator cable would be at geosynchronous altitude so the cable would have to be thickest there and taper as it approaches Earth. Any potential cable design may be characterized by the taper factor – the ratio between the cable's radius at geosynchronous altitude and at the Earth's surface.

The cable would need to be made of a material with a high tensile strength/density ratio. For example, the Edwards space elevator design assumes a cable material with a tensile strength of at least 100 gigapascals. Since Edwards consistently assumed the density of his carbon nanotube cable to be 1300 kg/m3, that implies a specific strength of 77 megapascal/(kg/m3). This value takes into consideration the entire weight of the space elevator. An untapered space elevator cable would need a material capable of sustaining a length of 4,960 kilometers (3,080 mi) of its own weight at sea level to reach a geostationary altitude of 35,786 km (22,236 mi) without yielding. Therefore, a material with very high strength and lightness is needed.

For comparison, metals like titanium, steel or aluminium alloys have breaking lengths of only 20–30 km (0.2–0.3 MPa/(kg/m3)). Modern fiber materials such as kevlar, fiberglass and carbon/graphite fiber have breaking lengths of 100–400 km (1.0–4.0 MPa/(kg/m3)). Nanoengineered materials such as carbon nanotubes and, more recently discovered, graphene ribbons (perfect two-dimensional sheets of carbon) are expected to have breaking lengths of 5000–6000 km (50–60 MPa/(kg/m3)), and also are able to conduct electrical power.

For a space elevator on Earth, with its comparatively high gravity, the cable material would need to be stronger and lighter than currently available materials. For this reason, there has been a focus on the development of new materials that meet the demanding specific strength requirement. For high specific strength, carbon has advantages because it is only the sixth element in the periodic table. Carbon has comparatively few of the protons and neutrons which contribute most of the dead weight of any material. Most of the interatomic bonding forces of any element are contributed by only the outer few electrons. For carbon, the strength and stability of those bonds is high compared to the mass of the atom. The challenge in using carbon nanotubes remains to extend to macroscopic sizes the production of such material that are still perfect on the microscopic scale (as microscopic defects are most responsible for material weakness). As of 2014, carbon nanotube technology allowed growing tubes up to a few tenths of meters.

In 2014, diamond nanothreads were first synthesized. Since they have strength properties similar to carbon nanotubes, diamond nanothreads were quickly seen as candidate cable material as well.

Climbers

A space elevator cannot be an elevator in the typical sense (with moving cables) due to the need for the cable to be significantly wider at the center than at the tips. While various designs employing moving cables have been proposed, most cable designs call for the "elevator" to climb up a stationary cable.

Climbers cover a wide range of designs. On elevator designs whose cables are planar ribbons, most propose to use pairs of rollers to hold the cable with friction.

Climbers would need to be paced at optimal timings so as to minimize cable stress and oscillations and to maximize throughput. Lighter climbers could be sent up more often, with several going up at the same time. This would increase throughput somewhat, but would lower the mass of each individual payload.

The horizontal speed, i.e. due to orbital rotation, of each part of the cable increases with altitude, proportional to distance from the center of the Earth, reaching low orbital speed at a point approximately 66 percent of the height between the surface and geostationary orbit, or a height of about 23,400 km. A payload released at this point would go into a highly eccentric elliptical orbit, staying just barely clear from atmospheric reentry, with the periapsis at the same altitude as LEO and the apoapsis at the release height. With increasing release height the orbit would become less eccentric as both periapsis and apoapsis increase, becoming circular at geostationary level.

When the payload has reached GEO, the horizontal speed is exactly the speed of a circular orbit at that level, so that if released, it would remain adjacent to that point on the cable. The payload can also continue climbing further up the cable beyond GEO, allowing it to obtain higher speed at jettison. If released from 100,000 km, the payload would have enough speed to reach the asteroid belt.

As a payload is lifted up a space elevator, it would gain not only altitude, but horizontal speed (angular momentum) as well. The angular momentum is taken from the Earth's rotation. As the climber ascends, it is initially moving slower than each successive part of cable it is moving on to. This is the Coriolis force: the climber "drags" (westward) on the cable, as it climbs, and slightly decreases the Earth's rotation speed. The opposite process would occur for descending payloads: the cable is tilted eastward, thus slightly increasing Earth's rotation speed.

The overall effect of the centrifugal force acting on the cable would cause it to constantly try to return to the energetically favorable vertical orientation, so after an object has been lifted on the cable, the counterweight would swing back toward the vertical, a bit like a pendulum. Space elevators and their loads would be designed so that the center of mass is always well-enough above the level of geostationary orbit to hold up the whole system. Lift and descent operations would need to be carefully planned so as to keep the pendulum-like motion of the counterweight around the tether point under control.

Climber speed would be limited by the Coriolis force, available power, and by the need to ensure the climber's accelerating force does not break the cable. Climbers would also need to maintain a minimum average speed in order to move material up and down economically and expeditiously. At the speed of a very fast car or train of 300 km/h (190 mph) it will take about 5 days to climb to geosynchronous orbit.

Powering climbers

Both power and energy are significant issues for climbers – the climbers would need to gain a large amount of potential energy as quickly as possible to clear the cable for the next payload.

Various methods have been proposed to provide energy to the climber:

- Transfer the energy to the climber through wireless energy transfer while it is climbing.

- Transfer the energy to the climber through some material structure while it is climbing.

- Store the energy in the climber before it starts – requires an extremely high specific energy such as nuclear energy.

- Solar power – After the first 40 km it is possible to use solar energy to power the climber.

Wireless energy transfer such as laser power beaming is currently considered the most likely method, using megawatt-powered free electron or solid state lasers in combination with adaptive mirrors approximately 10 m (33 ft) wide and a photovoltaic array on the climber tuned to the laser frequency for efficiency. For climber designs powered by power beaming, this efficiency is an important design goal. Unused energy would need to be re-radiated away with heat-dissipation systems, which add to weight.

Yoshio Aoki, a professor of precision machinery engineering at Nihon University and director of the Japan Space Elevator Association, suggested including a second cable and using the conductivity of carbon nanotubes to provide power.

Counterweight

Several solutions have been proposed to act as a counterweight:

- a heavy, captured asteroid

- a space dock, space station or spaceport positioned past geostationary orbit

- a further upward extension of the cable itself so that the net upward pull would be the same as an equivalent counterweight

- parked spent climbers that had been used to thicken the cable during construction, other junk, and material lifted up the cable for the purpose of increasing the counterweight.

Extending the cable has the advantage of some simplicity of the task and the fact that a payload that went to the end of the counterweight-cable would acquire considerable velocity relative to the Earth, allowing it to be launched into interplanetary space. Its disadvantage is the need to produce greater amounts of cable material as opposed to using just anything available that has mass.

Applications

Launching into deep space

An object attached to a space elevator at a radius of approximately 53,100 km would be at escape velocity when released. Transfer orbits to the L1 and L2 Lagrangian points could be attained by release at 50,630 and 51,240 km, respectively, and transfer to lunar orbit from 50,960 km.

At the end of Pearson's 144,000 km (89,000 mi) cable, the tangential velocity is 10.93 kilometers per second (6.79 mi/s). That is more than enough to escape Earth's gravitational field and send probes at least as far out as Jupiter. Once at Jupiter, a gravitational assist maneuver could permit solar escape velocity to be reached.

Extraterrestrial elevators

A space elevator could also be constructed on other planets, asteroids and moons.

A Martian tether could be much shorter than one on Earth. Mars' surface gravity is 38 percent of Earth's, while it rotates around its axis in about the same time as Earth. Because of this, Martian stationary orbit is much closer to the surface, and hence the elevator could be much shorter. Current materials are already sufficiently strong to construct such an elevator. Building a Martian elevator would be complicated by the Martian moon Phobos, which is in a low orbit and intersects the Equator regularly (twice every orbital period of 11 h 6 min). Phobos and Deimos may get in the way of an areostationary space elevator; on the other hand, they may contribute useful resources to the project. Phobos is projected to contain high amounts of carbon. If carbon nanotubes become feasible for a tether material, there will be an abundance of carbon near Mars. This could provide readily available resources for future colonization on Mars.

Phobos is tide-locked: one side always faces its primary, Mars. An elevator extending 6,000 km from that inward side would end about 28 kilometers above the Martian surface, just out of the denser parts of the atmosphere of Mars. A similar cable extending 6,000 km in the opposite direction would counterbalance the first, so the center of mass of this system remains in Phobos. In total the space elevator would extend out over 12,000 km which would be below areostationary orbit of Mars (17,032 km). A rocket launch would still be needed to get the rocket and cargo to the beginning of the space elevator 28 km above the surface. The surface of Mars is rotating at 0.25 km/s at the equator and the bottom of the space elevator would be rotating around Mars at 0.77 km/s, so only 0.52 km/s (1872 km/h) of Delta-v would be needed to get to the space elevator. Phobos orbits at 2.15 km/s and the outermost part of the space elevator would rotate around Mars at 3.52 km/s.

The Earth's Moon is a potential location for a Lunar space elevator, especially as the specific strength required for the tether is low enough to use currently available materials. The Moon does not rotate fast enough for an elevator to be supported by centrifugal force (the proximity of the Earth means there is no effective lunar-stationary orbit), but differential gravity forces means that an elevator could be constructed through Lagrangian points. A near-side elevator would extend through the Earth-Moon L1 point from an anchor point near the center of the visible part of Earth's Moon: the length of such an elevator must exceed the maximum L1 altitude of 59,548 km, and would be considerably longer to reduce the mass of the required apex counterweight. A far-side lunar elevator would pass through the L2 Lagrangian point and would need to be longer than on the near-side; again, the tether length depends on the chosen apex anchor mass, but it could also be made of existing engineering materials.

Rapidly spinning asteroids or moons could use cables to eject materials to convenient points, such as Earth orbits; or conversely, to eject materials to send a portion of the mass of the asteroid or moon to Earth orbit or a Lagrangian point. Freeman Dyson, a physicist and mathematician, suggested using such smaller systems as power generators at points distant from the Sun where solar power is uneconomical.

A space elevator using presently available engineering materials could be constructed between mutually tidally locked worlds, such as Pluto and Charon or the components of binary asteroid 90 Antiope, with no terminus disconnect, according to Francis Graham of Kent State University. However, spooled variable lengths of cable must be used due to ellipticity of the orbits.

Construction

The construction of a space elevator would need reduction of some technical risk. Some advances in engineering, manufacturing and physical technology are required. Once a first space elevator is built, the second one and all others would have the use of the previous ones to assist in construction, making their costs considerably lower. Such follow-on space elevators would also benefit from the great reduction in technical risk achieved by the construction of the first space elevator.

Prior to the work of Edwards in 2000, most concepts for constructing a space elevator had the cable manufactured in space. That was thought to be necessary for such a large and long object and for such a large counterweight. Manufacturing the cable in space would be done in principle by using an asteroid or Near-Earth object for source material. These earlier concepts for construction require a large preexisting space-faring infrastructure to maneuver an asteroid into its needed orbit around Earth. They also required the development of technologies for manufacture in space of large quantities of exacting materials.

Since 2001, most work has focused on simpler methods of construction requiring much smaller space infrastructures. They conceive the launch of a long cable on a large spool, followed by deployment of it in space. The spool would be initially parked in a geostationary orbit above the planned anchor point. A long cable would be dropped "downward" (toward Earth) and would be balanced by a mass being dropped "upward" (away from Earth) for the whole system to remain on the geosynchronous orbit. Earlier designs imagined the balancing mass to be another cable (with counterweight) extending upward, with the main spool remaining at the original geosynchronous orbit level. Most current designs elevate the spool itself as the main cable is payed out, a simpler process. When the lower end of the cable is long enough to reach the surface of the Earth (at the equator), it would be anchored. Once anchored, the center of mass would be elevated more (by adding mass at the upper end or by paying out more cable). This would add more tension to the whole cable, which could then be used as an elevator cable.

One plan for construction uses conventional rockets to place a "minimum size" initial seed cable of only 19,800 kg. This first very small ribbon would be adequate to support the first 619 kg climber. The first 207 climbers would carry up and attach more cable to the original, increasing its cross section area and widening the initial ribbon to about 160 mm wide at its widest point. The result would be a 750-ton cable with a lift capacity of 20 tons per climber.

Safety issues and construction challenges

For early systems, transit times from the surface to the level of geosynchronous orbit would be about five days. On these early systems, the time spent moving through the Van Allen radiation belts would be enough that passengers would need to be protected from radiation by shielding, which would add mass to the climber and decrease payload.

A space elevator would present a navigational hazard, both to aircraft and spacecraft. Aircraft could be diverted by air-traffic control restrictions. All objects in stable orbits that have perigee below the maximum altitude of the cable that are not synchronous with the cable would impact the cable eventually, unless avoiding action is taken. One potential solution proposed by Edwards is to use a movable anchor (a sea anchor) to allow the tether to "dodge" any space debris large enough to track.

Impacts by space objects such as meteoroids, micrometeorites and orbiting man-made debris pose another design constraint on the cable. A cable would need to be designed to maneuver out of the way of debris, or absorb impacts of small debris without breaking.

Economics

With a space elevator, materials might be sent into orbit at a fraction of the current cost. As of 2022, conventional rocket designs cost about US$12,125 per kilogram (US$5,500 per pound) for transfer to geostationary orbit. Current space elevator proposals envision payload prices starting as low as $220 per kilogram ($100 per pound), similar to the $5–$300/kg estimates of the Launch loop, but higher than the $310/ton to 500 km orbit quoted to Dr. Jerry Pournelle for an orbital airship system.

Philip Ragan, co-author of the book Leaving the Planet by Space Elevator, states that "The first country to deploy a space elevator will have a 95 percent cost advantage and could potentially control all space activities."

International Space Elevator Consortium (ISEC)

The International Space Elevator Consortium (ISEC) is a US Non-Profit 501(c)(3) Corporation formed to promote the development, construction, and operation of a space elevator as "a revolutionary and efficient way to space for all humanity". It was formed after the Space Elevator Conference in Redmond, Washington in July 2008 and became an affiliate organization with the National Space Society in August 2013. ISEC hosts an annual Space Elevator conference at the Seattle Museum of Flight.

ISEC coordinates with the two other major societies focusing on space elevators: the Japanese Space Elevator Association and EuroSpaceward. ISEC supports symposia and presentations at the International Academy of Astronautics and the International Astronautical Federation Congress each year.

Related concepts

The conventional current concept of a "Space Elevator" has evolved from a static compressive structure reaching to the level of GEO, to the modern baseline idea of a static tensile structure anchored to the ground and extending to well above the level of GEO. In the current usage by practitioners (and in this article), a "Space Elevator" means the Tsiolkovsky-Artsutanov-Pearson type as considered by the International Space Elevator Consortium. This conventional type is a static structure fixed to the ground and extending into space high enough that cargo can climb the structure up from the ground to a level where simple release will put the cargo into an orbit.

Some concepts related to this modern baseline are not usually termed a "Space Elevator", but are similar in some way and are sometimes termed "Space Elevator" by their proponents. For example, Hans Moravec published an article in 1977 called "A Non-Synchronous Orbital Skyhook" describing a concept using a rotating cable. The rotation speed would exactly match the orbital speed in such a way that the tip velocity at the lowest point was zero compared to the object to be "elevated". It would dynamically grapple and then "elevate" high flying objects to orbit or low orbiting objects to higher orbit.

The original concept envisioned by Tsiolkovsky was a compression structure, a concept similar to an aerial mast. While such structures might reach space (100 km, 62 mi), they are unlikely to reach geostationary orbit. The concept of a Tsiolkovsky tower combined with a classic space elevator cable (reaching above the level of GEO) has been suggested. Other ideas use very tall compressive towers to reduce the demands on launch vehicles. The vehicle is "elevated" up the tower, which may extend as high as above the atmosphere, and is launched from the top. Such a tall tower to access near-space altitudes of 20 km (12 mi) has been proposed by various researchers.

The aerovator is a concept invented by a Yahoo Group discussing space elevators, and included in a 2009 book about space elevators. It would consist of a >1000 km long ribbon extending diagonally upwards from a ground-level hub and then levelling out to become horizontal. Aircraft would pull on the ribbon while flying in a circle, causing the ribbon to rotate around the hub once every 13 minutes with its tip travelling at 8 km/s. The ribbon would stay in the air through a mix of aerodynamic lift and centrifugal force. Payloads would climb up the ribbon and then be launched from the fast-moving tip into orbit.

Other concepts for non-rocket spacelaunch related to a space elevator (or parts of a space elevator) include an orbital ring, a space fountain, a launch loop, a skyhook, a space tether, and a buoyant "SpaceShaft".

![{\displaystyle A(r)=A_{s}\exp \left[{\frac {\rho gR^{2}}{T}}\left({\frac {1}{R}}+{\frac {R^{2}}{2R_{g}^{3}}}-{\frac {1}{r}}-{\frac {r^{2}}{2R_{g}^{3}}}\right)\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2faccd127a8849f6dd878b215391810a2d589e15)

![{\displaystyle A(R_{g})/A_{s}=\exp \left[{\frac {\rho }{T}}\times 4.85\times 10^{7}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b72d33815544c2f3ddbc4392e335414437efe7d7)