Environmental science is an interdisciplinary academic field that integrates physics, biology, meteorology, mathematics and geography (including ecology, chemistry, plant science, zoology, mineralogy, oceanography, limnology, soil science, geology and physical geography, and atmospheric science) to the study of the environment, and the solution of environmental problems. Environmental science emerged from the fields of natural history and medicine during the Enlightenment. Today it provides an integrated, quantitative, and interdisciplinary approach to the study of environmental systems.

Environmental studies incorporates more of the social sciences for understanding human relationships, perceptions and policies towards the environment. Environmental engineering focuses on design and technology for improving environmental quality in every aspect.

Environmental scientists seek to understand the earth's physical, chemical, biological, and geological processes, and to use that knowledge to understand how issues such as alternative energy systems, pollution control and mitigation, natural resource management, and the effects of global warming and climate change influence and affect the natural systems and processes of earth. Environmental issues almost always include an interaction of physical, chemical, and biological processes. Environmental scientists bring a systems approach to the analysis of environmental problems. Key elements of an effective environmental scientist include the ability to relate space, and time relationships as well as quantitative analysis.

Environmental science came alive as a substantive, active field of scientific investigation in the 1960s and 1970s driven by (a) the need for a multi-disciplinary approach to analyze complex environmental problems, (b) the arrival of substantive environmental laws requiring specific environmental protocols of investigation and (c) the growing public awareness of a need for action in addressing environmental problems. Events that spurred this development included the publication of Rachel Carson's landmark environmental book Silent Spring along with major environmental issues becoming very public, such as the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill, and the Cuyahoga River of Cleveland, Ohio, "catching fire" (also in 1969), and helped increase the visibility of environmental issues and create this new field of study.

Terminology

In common usage, "environmental science" and "ecology" are often used interchangeably, but technically, ecology refers only to the study of organisms and their interactions with each other as well as how they interrelate with environment. Ecology could be considered a subset of environmental science, which also could involve purely chemical or public health issues (for example) ecologists would be unlikely to study. In practice, there are considerable similarities between the work of ecologists and other environmental scientists. There is substantial overlap between ecology and environmental science with the disciplines of fisheries, forestry, and wildlife.

History

Ancient civilizations

Historical concern for environmental issues is well documented in archives around the world. Ancient civilizations were mainly concerned with what is now known as environmental science insofar as it related to agriculture and natural resources. Scholars believe that early interest in the environment began around 6000 BCE when ancient civilizations in Israel and Jordan collapsed due to deforestation. As a result, in 2700 BCE the first legislation limiting deforestation was established in Mesopotamia. Two hundred years later, in 2500 BCE, a community residing in the Indus River Valley observed the nearby river system in order to improve sanitation. This involved manipulating the flow of water to account for public health. In the Western Hemisphere, numerous ancient Central American city-states collapsed around 1500 BCE due to soil erosion from intensive agriculture. Those remaining from these civilizations took greater attention to the impact of farming practices on the sustainability of the land and its stable food production. Furthermore, in 1450 BCE the Minoan civilization on the Greek island of Crete declined due to deforestation and the resulting environmental degradation of natural resources. Pliny the Elder somewhat addressed the environmental concerns of ancient civilizations in the text Naturalis Historia, written between 77 and 79 ACE, which provided an overview of many related subsets of the discipline.

Although warfare and disease were of primary concern in ancient society, environmental issues played a crucial role in the survival and power of different civilizations. As more communities recognized the importance of the natural world to their long-term success, an interest in studying the environment came into existence.

Beginnings of environmental science

18th century

In 1735, the concept of binomial nomenclature is introduced by Carolus Linnaeus as a way to classify all living organisms, influenced by earlier works of Aristotle. His text, Systema Naturae, represents one of the earliest culminations of knowledge on the subject, providing a means to identify different species based partially on how they interact with their environment.

19th century

In the 1820s, scientists were studying the properties of gases, particularly those in the Earth's atmosphere and their interactions with heat from the Sun. Later that century, studies suggested that the Earth had experienced an Ice Age and that warming of the Earth was partially due to what are now known as greenhouse gases (GHG). The greenhouse effect was introduced, although climate science was not yet recognized as an important topic in environmental science due to minimal industrialization and lower rates of greenhouse gas emissions at the time.

20th century

In the 1900s, the discipline of environmental science as it is known today began to take shape. The century is marked by significant research, literature, and international cooperation in the field.

In the early 20th century, criticism from dissenters downplayed the effects of global warming. At this time, few researchers were studying the dangers of fossil fuels. After a 1.3 degrees Celsius temperature anomaly was found in the Atlantic Ocean in the 1940s, however, scientists renewed their studies of gaseous heat trapping from the greenhouse effect (although only carbon dioxide and water vapor were known to be greenhouse gases then). Nuclear development following the Second World War allowed environmental scientists to intensively study the effects of carbon and make advancements in the field. Further knowledge from archaeological evidence brought to light the changes in climate over time, particularly ice core sampling.

Environmental science was brought to the forefront of society in 1962 when Rachel Carson published an influential piece of environmental literature, Silent Spring. Carson's writing led the American public to pursue environmental safeguards, such as bans on harmful chemicals like the insecticide DDT. Another important work, The Tragedy of the Commons, was published by Garrett Hardin in 1968 in response to accelerating natural degradation. In 1969, environmental science once again became a household term after two striking disasters: Ohio's Cuyahoga River caught fire due to the amount of pollution in its waters and a Santa Barbara oil spill endangered thousands of marine animals, both receiving prolific media coverage. Consequently, the United States passed an abundance of legislation, including the Clean Water Act and the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. The following year, in 1970, the first ever Earth Day was celebrated worldwide and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was formed, legitimizing the study of environmental science in government policy. In the next two years, the United Nations created the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in Stockholm, Sweden to address global environmental degradation.

Much of the interest in environmental science throughout the 1970s and the 1980s was characterized by major disasters and social movements. In 1978, hundreds of people were relocated from Love Canal, New York after carcinogenic pollutants were found to be buried underground near residential areas. The next year, in 1979, the nuclear power plant on Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania suffered a meltdown and raised concerns about the dangers of radioactive waste and the safety of nuclear energy. In response to landfills and toxic waste often disposed of near their homes, the official Environmental Justice Movement was started by a Black community in North Carolina in 1982. Two years later, the toxic methyl isocyanate gas was released to the public from a power plant disaster in Bhopal, India, harming hundreds of thousands of people living near the disaster site, the effects of which are still felt today. In a groundbreaking discovery in 1985, a British team of researchers studying Antarctica found evidence of a hole in the ozone layer, inspiring global agreements banning the use of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which were previously used in nearly all aerosols and refrigerants. Notably, in 1986, the meltdown at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine released radioactive waste to the public, leading to international studies on the ramifications of environmental disasters. Over the next couple of years, the Brundtland Commission (previously known as the World Commission on Environment and Development) published a report titled Our Common Future and the Montreal Protocol formed the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as international communication focused on finding solutions for climate change and degradation. In the late 1980s, the Exxon Valdez company was fined for spilling large quantities of crude oil off the coast of Alaska and the resulting cleanup, involving the work of environmental scientists. After hundreds of oil wells were burned in combat in 1991, warfare between Iraq and Kuwait polluted the surrounding atmosphere just below the air quality threshold environmental scientists believed was life-threatening.

21st century

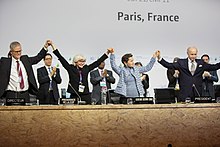

Many niche disciplines of environmental science have emerged over the years, although climatology is one of the most known topics. Since the 2000s, environmental scientists have focused on modeling the effects of climate change and encouraging global cooperation to minimize potential damages. In 2002, the Society for the Environment as well as the Institute of Air Quality Management were founded to share knowledge and develop solutions around the world. Later, in 2008, the United Kingdom became the first country to pass legislation (the Climate Change Act) that aims to reduce carbon dioxide output to a specified threshold. In 2016 the Kyoto Protocol became the Paris Agreement, which sets concrete goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and restricts Earth's rise in temperature to a 2 degrees Celsius maximum. The agreement is one of the most expansive international efforts to limit the effects of global warming to date.

Most environmental disasters in this time period involve crude oil pollution or the effects of rising temperatures. In 2010, BP was responsible for the largest American oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, known as the Deepwater Horizon spill, which killed a number of the company's workers and released large amounts of crude oil into the water. Furthermore, throughout this century, much of the world has been ravaged by widespread wildfires and water scarcity, prompting regulations on the sustainable use of natural resources as determined by environmental scientists.

The 21st century is marked by significant technological advancements. New technology in environmental science has transformed how researchers gather information about various topics in the field. Research in engines, fuel efficiency, and decreasing emissions from vehicles since the times of the Industrial Revolution has reduced the amount of carbon and other pollutants into the atmosphere. Furthermore, investment in researching and developing clean energy (i.e. wind, solar, hydroelectric, and geothermal power) has significantly increased in recent years, indicating the beginnings of the divestment from fossil fuel use. Geographic information systems (GIS) are used to observe sources of air or water pollution through satellites and digital imagery analysis. This technology allows for advanced farming techniques like precision agriculture as well as monitoring water usage in order to set market prices. In the field of water quality, developed strains of natural and manmade bacteria contribute to bioremediation, the treatment of wastewaters for future use. This method is more eco-friendly and cheaper than manual cleanup or treatment of wastewaters. Most notably, the expansion of computer technology has allowed for large data collection, advanced analysis, historical archives, public awareness of environmental issues, and international scientific communication. The ability to crowdsource on the Internet, for example, represents the process of collectivizing knowledge from researchers around the world to create increased opportunity for scientific progress. With crowdsourcing, data is released to the public for personal analyses which can later be shared as new information is found. Another technological development, blockchain technology, monitors and regulates global fisheries. By tracking the path of fish through global markets, environmental scientists can observe whether certain species are being overharvested to the point of extinction. Additionally, remote sensing allows for the detection of features of the environment without physical intervention. The resulting digital imagery is used to create increasingly accurate models of environmental processes, climate change, and much more. Advancements to remote sensing technology are particularly useful in locating the nonpoint sources of pollution and analyzing ecosystem health through image analysis across the electromagnetic spectrum. Lastly, thermal imaging technology is used in wildlife management to catch and discourage poachers and other illegal wildlife traffickers from killing endangered animals, proving useful for conservation efforts. Artificial intelligence has also been used to predict the movement of animal populations and protect the habitats of wildlife.

Components

Atmospheric sciences

Atmospheric sciences focus on the Earth's atmosphere, with an emphasis upon its interrelation to other systems. Atmospheric sciences can include studies of meteorology, greenhouse gas phenomena, atmospheric dispersion modeling of airborne contaminants, sound propagation phenomena related to noise pollution, and even light pollution.

Taking the example of the global warming phenomena, physicists create computer models of atmospheric circulation and infrared radiation transmission, chemists examine the inventory of atmospheric chemicals and their reactions, biologists analyze the plant and animal contributions to carbon dioxide fluxes, and specialists such as meteorologists and oceanographers add additional breadth in understanding the atmospheric dynamics.

Ecology

As defined by the Ecological Society of America, "Ecology is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment; it seeks to understand the vital connections between plants and animals and the world around them." Ecologists might investigate the relationship between a population of organisms and some physical characteristic of their environment, such as concentration of a chemical; or they might investigate the interaction between two populations of different organisms through some symbiotic or competitive relationship. For example, an interdisciplinary analysis of an ecological system which is being impacted by one or more stressors might include several related environmental science fields. In an estuarine setting where a proposed industrial development could impact certain species by water and air pollution, biologists would describe the flora and fauna, chemists would analyze the transport of water pollutants to the marsh, physicists would calculate air pollution emissions and geologists would assist in understanding the marsh soils and bay muds.

Environmental chemistry

Environmental chemistry is the study of chemical alterations in the environment. Principal areas of study include soil contamination and water pollution. The topics of analysis include chemical degradation in the environment, multi-phase transport of chemicals (for example, evaporation of a solvent containing lake to yield solvent as an air pollutant), and chemical effects upon biota.

As an example study, consider the case of a leaking solvent tank which has entered the habitat soil of an endangered species of amphibian. As a method to resolve or understand the extent of soil contamination and subsurface transport of solvent, a computer model would be implemented. Chemists would then characterize the molecular bonding of the solvent to the specific soil type, and biologists would study the impacts upon soil arthropods, plants, and ultimately pond-dwelling organisms that are the food of the endangered amphibian.

Geosciences

Geosciences include environmental geology, environmental soil science, volcanic phenomena and evolution of the Earth's crust. In some classification systems this can also include hydrology, including oceanography.

As an example study, of soils erosion, calculations would be made of surface runoff by soil scientists. Fluvial geomorphologists would assist in examining sediment transport in overland flow. Physicists would contribute by assessing the changes in light transmission in the receiving waters. Biologists would analyze subsequent impacts to aquatic flora and fauna from increases in water turbidity.

Regulations driving the studies

In the United States the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969 set forth requirements for analysis of federal government actions (such as highway construction projects and land management decisions) in terms of specific environmental criteria. Numerous state laws have echoed these mandates, applying the principles to local-scale actions. The upshot has been an explosion of documentation and study of environmental consequences before the fact of development actions.

One can examine the specifics of environmental science by reading examples of Environmental Impact Statements prepared under NEPA such as: Wastewater treatment expansion options discharging into the San Diego/Tijuana Estuary, Expansion of the San Francisco International Airport, Development of the Houston, Metro Transportation system, Expansion of the metropolitan Boston MBTA transit system, and Construction of Interstate 66 through Arlington, Virginia.

In England and Wales the Environment Agency (EA), formed in 1996, is a public body for protecting and improving the environment and enforces the regulations listed on the communities and local government site. (formerly the office of the deputy prime minister). The agency was set up under the Environment Act 1995 as an independent body and works closely with UK Government to enforce the regulations.