Power-to-gas (often abbreviated P2G) is a technology that uses electric power to produce a gaseous fuel.

Most P2G systems use electrolysis to produce hydrogen. The hydrogen can be used directly, or further steps (known as two-stage P2G systems) may convert the hydrogen into syngas, methane, or LPG. Single-stage P2G systems to produce methane also exist, such as reversible solid oxide cell (rSOC) technology.

Produced gas, just like natural gas or industrially produced hydrogen or methane, is a commodity and may be used as such through existing infrastructure (pipelines and gas storage facilities), including back to power at a loss. However, provided the power comes from renewable energy, it can be touted as a carbon-neutral fuel, renewable, and a way to store variable renewable energy.

Power-to-hydrogen

All current P2G systems start by using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen by means of electrolysis. In a "power-to-hydrogen" system, the resulting hydrogen is injected into the natural gas grid or is used in transport or industry rather than being used to produce another gas type.

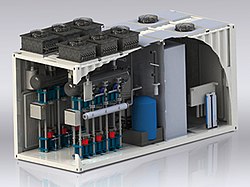

ITM Power won a tender in March 2013 for a Thüga Group project, to supply a 360 kW self-pressurising high-pressure electrolysis rapid response proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyser Rapid Response Electrolysis Power-to-Gas energy storage plant. The unit produces 125 kg/day of hydrogen gas and incorporates AEG power electronics. It will be situated at a Mainova AG site in the Schielestraße, Frankfurt in the state of Hessen. The operational data will be shared by the whole Thüga group – the largest network of energy companies in Germany with around 100 municipal utility members. The project partners include: badenova AG & Co. kg, Erdgas Mittelsachsen GmbH, Energieversorgung Mittelrhein GmbH, erdgas schwaben GmbH, Gasversorgung Westerwald GmbH, Mainova Aktiengesellschaft, Stadtwerke Ansbach GmbH, Stadtwerke Bad Hersfeld GmbH, Thüga Energienetze GmbH, WEMAG AG, e-rp GmbH, ESWE Versorgungs AG with Thüga Aktiengesellschaft as project coordinator. Scientific partners will participate in the operational phase. It can produce 60 cubic metres of hydrogen per hour and feed 3,000 cubic metres of natural gas enriched with hydrogen into the grid per hour. An expansion of the pilot plant is planned from 2016, facilitating the full conversion of the hydrogen produced into methane to be directly injected into the natural gas grid.

In December 2013, ITM Power, Mainova, and NRM Netzdienste Rhein-Main GmbH began injecting hydrogen into the German gas distribution network using ITM Power HGas, which is a rapid response proton exchange membrane electrolyser plant. The power consumption of the electrolyser is 315 kilowatts. It produces about 60 cubic meters per hour of hydrogen and thus in one hour can feed 3,000 cubic meters of hydrogen-enriched natural gas into the network.

On August 28, 2013, E.ON Hanse, Solvicore, and Swissgas inaugurated a commercial power-to-gas unit in Falkenhagen, Germany. The unit, which has a capacity of two megawatts, can produce 360 cubic meters of hydrogen per hour. The plant uses wind power and Hydrogenics electrolysis equipment to transform water into hydrogen, which is then injected into the existing regional natural gas transmission system. Swissgas, which represents over 100 local natural gas utilities, is a partner in the project with a 20 percent capital stake and an agreement to purchase a portion of the gas produced. A second 800 kW power-to-gas project has been started in Hamburg/Reitbrook district and is expected to open in 2015.

In August 2013, a 140 MW wind park in Grapzow, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern owned by E.ON received an electrolyser. The hydrogen produced can be used in an internal combustion engine or can be injected into the local gas grid. The hydrogen compression and storage system stores up to 27 MWh of energy and increases the overall efficiency of the wind park by tapping into wind energy that otherwise would be wasted. The electrolyser produces 210 Nm3/h of hydrogen and is operated by RH2-WKA.

The INGRID project started in 2013 in Apulia, Italy. It is a four-year project with 39 MWh storage and a 1.2 MW electrolyser for smart grid monitoring and control. The hydrogen is used for grid balancing, transport, industry, and injection into the gas network.

The surplus energy from the 12 MW Prenzlau Windpark in Brandenburg, Germany will be injected into the gas grid from 2014 on.

The 6 MW Energiepark Mainz from Stadtwerke Mainz, RheinMain University of Applied Sciences, Linde and Siemens in Mainz (Germany) will open in 2015.

Power to gas and other energy storage schemes to store and utilize renewable energy are part of Germany's Energiewende (energy transition program).

In France, the MINERVE demonstrator of AFUL Chantrerie (Federation of Local Utilities Association) aims to promote the development of energy solutions for the future with elected representatives, companies and more generally civil society. It aims to experiment with various reactors and catalysts. The synthetic methane produced by the MINERVE demonstrator (0.6 Nm3 / h of CH4) is recovered as CNG fuel, which is used in the boilers of the AFUL Chantrerie boiler plant. The installation was designed and built by the French SME Top Industrie, with the support of Leaf. In November 2017 it achieved the predicted performance, 93.3% of CH4. This project was supported by the ADEME and the ERDF-Pays de la Loire Region, as well as by several other partners: Conseil départemental de Loire -Atlantic, Engie-Cofely, GRDF, GRTGaz, Nantes-Metropolis, Sydela and Sydev.

A full scale 1GW electrolyzer operated by EWE and Tree Energy Solutions is planned at the gas terminal in Wilhelmshaven, Germany. The first 500 MW is expected to begin operation in 2028. Wilhelmshaven can accommodate a second plant, bringing total potential capacity to 2GW.

Grid injection without compression

The core of the system is a proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyser. The electrolyser converts electrical energy into chemical energy, which in turn facilitates the storage of electricity. A gas mixing plant ensures that the proportion of hydrogen in the natural gas stream does not exceed two per cent by volume, the technically permissible maximum value when a natural gas filling station is situated in the local distribution network. The electrolyser supplies the hydrogen-methane mixture at the same pressure as the gas distribution network, namely 3.5 bar.

Power-to-methane

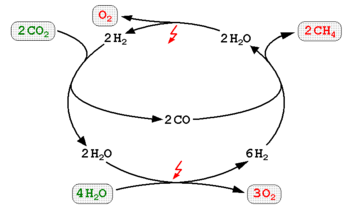

A power-to-methane system combines hydrogen from a power-to-hydrogen system with carbon dioxide to produce methane (see natural gas) using a methanation reaction such as the Sabatier reaction or biological methanation resulting in an extra energy conversion loss of 8%, the methane may then be fed into the natural gas grid if the purity requirement is reached.

ZSW (Center for Solar Energy and Hydrogen Research) and SolarFuel GmbH (now ETOGAS GmbH) realized a demonstration project with 250 kW electrical input power in Stuttgart, Germany. The plant was put into operation on October 30, 2012.

The first industry-scale Power-to-Methane plant was realized by ETOGAS for Audi AG in Werlte, Germany. The plant with 6 MW electrical input power is using CO2 from a waste-biogas plant and intermittent renewable power to produce synthetic natural gas (SNG) which is directly fed into the local gas grid (which is operated by EWE). The plant is part of the Audi e-fuels program. The produced synthetic natural gas, named Audi e-gas, enables CO2-neutral mobility with standard CNG vehicles. Currently it is available to customers of Audi's first CNG car, the Audi A3 g-tron.

In April 2014 the European Union's co-financed and from the KIT coordinated HELMETH (Integrated High-Temperature ELectrolysis and METHanation for Effective Power to Gas Conversion) research project started. The objective of the project is the proof of concept of a highly efficient Power-to-Gas technology by thermally integrating high temperature electrolysis (SOEC technology) with CO2-methanation. Through the thermal integration of exothermal methanation and steam generation for the high temperature steam electrolysis conversion efficiency > 85% (higher heating value of produced methane per used electrical energy) are theoretically possible. The process consists of a pressurized high-temperature steam electrolysis and a pressurized CO2-methanation module. The project was completed in 2017 and achieved an efficiency of 76% for the prototype with an indicated growth potential of 80% for industrial scale plants. The operating conditions of the CO2-methanation are a gas pressure of 10 - 30 bar, a SNG production of 1 - 5.4 m3/h (NTP) and a reactant conversion that produces SNG with H2 < 2 vol.-% resp. CH4 > 97 vol.-%. Thus, the generated substitute natural gas can be injected in the entire German natural gas network without limitations. As a cooling medium for the exothermic reaction boiling water is used at up to 300 °C, which corresponds to a water vapour pressure of about 87 bar. The SOEC works with a pressure of up to 15 bar, steam conversions of up to 90% and generates one standard cubic meter of hydrogen from 3.37 kWh of electricity as feed for the methanation.

The technological maturity of Power to Gas is evaluated in the European 27 partner project STORE&GO, which has started in March 2016 with a runtime of four years. Three different technological concepts are demonstrated in three different European countries (Falkenhagen/Germany, Solothurn/Switzerland, Troia/Italy). The technologies involved include biological and chemical methanation, direct capture of CO2 from atmosphere, liquefaction of the synthesized methane to bio-LNG, and direct injection into the gas grid. The overall goal of the project is to assess those technologies and various usage paths under technical, economic, and legal aspects to identify business cases on the short and on the long term. The project is co-funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (18 million euro) and the Swiss government (6 million euro), with another 4 million euro coming from participating industrial partners. The coordinator of the overall project is the research center of the DVGW located at the KIT.

Microbial methanation

The biological methanation combines both processes, the electrolysis of water to form hydrogen and the subsequent CO2 reduction to methane using this hydrogen. During this process, methane forming microorganisms (methanogenic archaea or methanogens) release enzymes that reduce the overpotential of a non-catalytic electrode (the cathode) so that it can produce hydrogen. This microbial power-to-gas reaction occurs at ambient conditions, i.e. room temperature and pH 7, at efficiencies that routinely reach 80-100%. However, methane is formed more slowly than in the Sabatier reaction due to the lower temperatures. A direct conversion of CO2 to methane has also been postulated, circumventing the need for hydrogen production. Microorganisms involved in the microbial power-to-gas reaction are typically members of the order Methanobacteriales. Genera that were shown to catalyze this reaction are Methanobacterium, Methanobrevibacter, and Methanothermobacter (thermophile).

LPG production

Methane can be used to produce LPG by synthesising SNG with partial reverse hydrogenation at high pressure and low temperature. LPG in turn can be converted into alkylate which is a premium gasoline blending stock because it has exceptional antiknock properties and gives clean burning.

Power to food

The synthetic methane generated from electricity can also be used for generating protein rich feed for cattle, poultry and fish economically by cultivating Methylococcus capsulatus bacteria culture with tiny land and water footprint. The carbon dioxide gas produced as by-product from these plants can be recycled in the generation of synthetic methane (SNG). Similarly, oxygen gas produced as by product from the electrolysis of water and the methanation process can be consumed in the cultivation of bacteria culture. With these integrated plants, the abundant renewable solar and wind power potential can be converted into high value food products without any water pollution or greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Biogas-upgrading to biomethane

In the third method the carbon dioxide in the output of a wood gas generator or a biogas plant after the biogas upgrader is mixed with the produced hydrogen from the electrolyzer to produce methane. The free heat coming from the electrolyzer is used to cut heating costs in the biogas plant. The impurities carbon dioxide, water, hydrogen sulfide, and particulates must be removed from the biogas if the gas is used for pipeline storage to prevent damage.

2014-Avedøre wastewater Services in Avedøre, Kopenhagen (Denmark) is adding a 1 MW electrolyzer plant to upgrade the anaerobic digestion biogas from sewage sludge. The produced hydrogen is used with the carbon dioxide from the biogas in a Sabatier reaction to produce methane. Electrochaea is testing another project outside P2G BioCat with biocatalytic methanation. The company uses an adapted strain of the thermophilic methanogen Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus and has demonstrated its technology at laboratory-scale in an industrial environment. A pre-commercial demonstration project with a 10,000-liter reactor vessel was executed between January and November 2013 in Foulum, Denmark.

In 2016 Torrgas, Siemens, Stedin, Gasunie, A.Hak, Hanzehogeschool/EnTranCe and Energy Valley intend to open a 12 MW Power to Gas facility in Delfzijl (The Netherlands) where biogas from Torrgas (biocoal) will be upgraded with hydrogen from electrolysis and delivered to nearby industrial consumers.

Power-to-syngas

| Water | CO2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrolysis of Water | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxygen | Hydrogen | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Conversion Reactor | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | Hydrogen | CO | |||||||||||||||||||

Syngas is a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide. It has been used since Victorian times, when it was produced from coal and known as "towngas". A power-to-syngas system uses hydrogen from a power-to-hydrogen system to produce syngas.

- 1st step: Electrolysis of Water (SOEC) −water is split into hydrogen and oxygen.

- 2nd step: Conversion Reactor (RWGSR) −hydrogen and carbon dioxide are inputs to the Conversion Reactor that outputs hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and water. 3H2 + CO2 → (2H2 + CO)syngas + H2O

- Syngas is used to produce synfuels.

Initiatives

Other initiatives to create syngas from carbon dioxide and water may use different water splitting methods.

- CSP

- 2004 Sunshine-to-Petrol —Sandia National Laboratories.

- 2013 NewCO2Fuels —New CO2 Fuels Ltd (IL) and Weizmann Institute of Science.

- 2014 Solar-Jet Fuels —Consortium partners ETH, SHELL, DLR, Bauhaus Luftfahrt, ARTTIC.

- HTE / Alkaline water electrolysis

- 2004 Syntrolysis Fuels —Idaho National Laboratory and Ceramatec, Inc. (US).

- 2008 WindFuels —Doty Energy (US).

- 2012 Air Fuel Synthesis —Air Fuel Synthesis Ltd (UK). Air Fuel Synthesis Ltd have become insolvent.

- 2013 Green Feed —BGU and Israel Strategic Alternative Energy Foundation (I-SAEF).

- 2014 E-diesel —Sunfire, a clean technology company and Audi.

The US Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) is designing a power-to-liquids system using the Fischer-Tropsch Process to create fuel on board a ship at sea, with the base products carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O) being derived from sea water via "An Electrochemical Module Configuration For The Continuous Acidification Of Alkaline Water Sources And Recovery Of CO2 With Continuous Hydrogen Gas Production".

Energy storage and transport

Power-to-gas systems may be deployed as adjuncts to wind parks or solar power plants. The excess power or off-peak power generated by wind generators or solar arrays may then be used hours, days, or months later to produce electrical power for the electrical grid. In the case of Germany, before switching to natural gas, the gas networks were operated using towngas, which for 50–60 % consisted of hydrogen. The storage capacity of the German natural gas network is more than 200,000 GWh which is enough for several months of energy requirement. By comparison, the capacity of all German pumped-storage hydroelectricity plants amounts to only about 40 GWh. Natural gas storage is a mature industry that has been in existence since Victorian times. The storage/retrieval power rate requirement in Germany is estimated at 16 GW in 2023, 80 GW in 2033 and 130 GW in 2050. The storage costs per kilowatt hour are estimated at €0.10 for hydrogen and €0.15 for methane.

The existing natural gas transport infrastructure conveys massive amounts of gas for long distances profitably using pipelines. It is now profitable to ship natural gas between continents using LNG carriers. The transport of energy through a gas network is done with much less loss (<0.1%) than in an electrical transmission network (8%). This infrastructure can transport methane produced by P2G without modification. It is possible to use it for up to 20% hydrogen. The use of the existing natural gas pipelines for hydrogen was studied by the EU NaturalHy project and the United States Department of Energy (DOE). Blending technology is also used in HCNG.

Efficiency

In 2013, the round-trip efficiency of power-to-gas-storage was well below 50%, with the hydrogen path being able to reach a maximum efficiency of ~ 43% and methane of ~ 39% by using combined cycle power plants. If cogeneration plants are used that produce both electricity and heat, efficiency can be above 60%, but is still less than pumped hydro or battery storage. However, there is potential to increase the efficiency of power-to-gas storage. In 2015 a study published in Energy and Environmental Science found that by using reversible solid oxide cells and recycling waste heat in the storage process, electricity-to-electricity round-trip efficiencies exceeding 70% can be reached at low cost. In addition, a 2018 study using pressurized reversible solid oxide cells and a similar methodology found that round-trip efficiencies (power-to-power) of up to 80% might be feasible.

| Fuel | Efficiency | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway: Electricity→Gas | ||

| Hydrogen | 54–72 % | 200 bar compression |

| Methane (SNG) | 49–64 % | |

| Hydrogen | 57–73 % | 80 bar compression (Natural gas pipeline) |

| Methane (SNG) | 50–64 % | |

| Hydrogen | 64–77 % | without compression |

| Methane (SNG) | 51–65 % | |

| Pathway: Electricity→Gas→Electricity | ||

| Hydrogen | 34–44 % | 80 bar compression up to 60% back to electricity |

| Methane (SNG) | 30–38 % | |

| Pathway: Electricity→Gas→Electricity & heat (cogeneration) | ||

| Hydrogen | 48–62 % | 80 bar compression and electricity/heat for 40/45 % |

| Methane (SNG) | 43–54 % | |

Electrolysis technology

- Relative advantages and disadvantages of electrolysis technologies.

| Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|

| Commercial technology (high technology readiness level) | Limited cost reduction and efficiency improvement potential |

| Low investment electrolyser | High maintenance intensity |

| Large stack size | Modest reactivity, ramp rates and flexibility (minimal load 20%) |

| Extremely low hydrogen impurity (0.001%) | Stacks < 250 kW require unusual AC/DC converters |

| Corrosive electrolyte deteriorates when not operating nominally |

| Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|

| Reliable technology (no kinetics) and simple, compact design | High investment costs (noble metals, membrane) |

| Very fast response time | Limited lifetime of membranes |

| Cost reduction potential (modular design) | Requires high water purity |

| Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|

| Highest electrolysis efficiency | Very low technology readiness level (proof of concept) |

| Low capital costs | Poor lifetime because of high temperature and affected material stability |

| Possibilities for integration with chemical methanation (heat recycling) | Limited flexibility; constant load required |