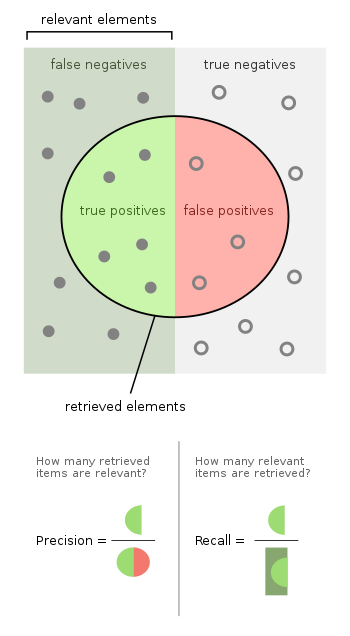

In statistical analysis of binary classification and information retrieval systems, the F-score or F-measure is a measure of predictive performance. It is calculated from the precision and recall of the test, where the precision is the number of true positive results divided by the number of all samples predicted to be positive, including those not identified correctly, and the recall is the number of true positive results divided by the number of all samples that should have been identified as positive. Precision is also known as positive predictive value, and recall is also known as sensitivity in diagnostic binary classification.

The F1 score is the harmonic mean of the precision and recall. It thus symmetrically represents both precision and recall in one metric. The more generic score applies additional weights, valuing one of precision or recall more than the other.

The highest possible value of an F-score is 1.0, indicating perfect precision and recall, and the lowest possible value is 0, if the precision or the recall is zero.

Etymology

The name F-measure is believed to be named after a different F function in Van Rijsbergen's book, when introduced to the Fourth Message Understanding Conference (MUC-4, 1992).

Definition

The traditional F-measure or balanced F-score (F1 score) is the harmonic mean of precision and recall:

Fβ score

A more general F score, , that uses a positive real factor , where is chosen such that recall is considered times as important as precision, is:

In terms of Type I and type II errors this becomes:

Two commonly used values for are 2, which weighs recall higher than precision, and 0.5, which weighs recall lower than precision.

The F-measure was derived so that "measures the effectiveness of retrieval with respect to a user who attaches times as much importance to recall as precision". It is based on Van Rijsbergen's effectiveness measure

Their relationship is: where

Diagnostic testing

This is related to the field of binary classification where recall is often termed "sensitivity".

|

|

|

Predicted condition | |||

| Total population = P + N |

Predicted positive | Predicted negative | Informedness, bookmaker informedness (BM) = TPR + TNR − 1 |

Prevalence threshold (PT) = √TPR × FPR - FPR/TPR - FPR | |

Actual condition

|

Positive (P)

|

True positive (TP), hit |

False negative (FN), miss, underestimation |

True positive rate (TPR), recall, sensitivity (SEN), probability of detection, hit rate, power = TP/P = 1 − FNR |

False negative rate (FNR), miss rate type II error = FN/P = 1 − TPR |

| Negative (N) | False positive (FP), false alarm, overestimation |

True negative (TN), correct rejection |

False positive rate (FPR), probability of false alarm, fall-out type I error = FP/N = 1 − TNR |

True negative rate (TNR), specificity (SPC), selectivity = TN/N = 1 − FPR | |

|

|

Prevalence = P/P + N |

Positive predictive value (PPV), precision = TP/TP + FP = 1 − FDR |

False omission rate (FOR) = FN/TN + FN = 1 − NPV |

Positive likelihood ratio (LR+) = TPR/FPR |

Negative likelihood ratio (LR−) = FNR/TNR |

| Accuracy (ACC) = TP + TN/P + N |

False discovery rate (FDR) = FP/TP + FP = 1 − PPV |

Negative predictive value (NPV) = TN/TN + FN = 1 − FOR |

Markedness (MK), deltaP (Δp) = PPV + NPV − 1 |

Diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) = LR+/LR− | |

| Balanced accuracy (BA) = TPR + TNR/2 |

F1 score = 2 PPV × TPR/PPV + TPR = 2 TP/2 TP + FP + FN |

Fowlkes–Mallows index (FM) = √PPV × TPR |

Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) = √TPR × TNR × PPV × NPV - √FNR × FPR × FOR × FDR |

Threat score (TS), critical success index (CSI), Jaccard index = TP/TP + FN + FP | |

Type I error: A test result which wrongly indicates that a particular condition or attribute is present

Dependence of the F-score on class imbalance

Precision-recall curve, and thus the score, explicitly depends on the ratio of positive to negative test cases. This means that comparison of the F-score across different problems with differing class ratios is problematic. One way to address this issue (see e.g., Siblini et al., 2020) is to use a standard class ratio when making such comparisons.

Applications

The F-score is often used in the field of information retrieval for measuring search, document classification, and query classification performance. It is particularly relevant in applications which are primarily concerned with the positive class and where the positive class is rare relative to the negative class.

Earlier works focused primarily on the F1 score, but with the proliferation of large scale search engines, performance goals changed to place more emphasis on either precision or recall and so is seen in wide application.

The F-score is also used in machine learning. However, the F-measures do not take true negatives into account, hence measures such as the Matthews correlation coefficient, Informedness or Cohen's kappa may be preferred to assess the performance of a binary classifier.

The F-score has been widely used in the natural language processing literature, such as in the evaluation of named entity recognition and word segmentation.

Properties

The F1 score is the Dice coefficient of the set of retrieved items and the set of relevant items.

- The F1-score of a classifier which always predicts the positive class converges to 1 as the probability of the positive class increases.

- The F1-score of a classifier which always predicts the positive class is equal to 2 * proportion_of_positive_class / ( 1 + proportion_of_positive_class ), since the recall is 1, and the precision is equal to the proportion of the positive class.

- If the scoring model is uninformative (cannot distinguish between the positive and negative class) then the optimal threshold is 0 so that the positive class is always predicted.

- F1 score is concave in the true positive rate.

Criticism

David Hand and others criticize the widespread use of the F1 score since it gives equal importance to precision and recall. In practice, different types of mis-classifications incur different costs. In other words, the relative importance of precision and recall is an aspect of the problem.

According to Davide Chicco and Giuseppe Jurman, the F1 score is less truthful and informative than the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) in binary evaluation classification.

David M W Powers has pointed out that F1 ignores the True Negatives and thus is misleading for unbalanced classes, while kappa and correlation measures are symmetric and assess both directions of predictability - the classifier predicting the true class and the true class predicting the classifier prediction, proposing separate multiclass measures Informedness and Markedness for the two directions, noting that their geometric mean is correlation.

Another source of critique of F1 is its lack of symmetry. It means it may change its value when dataset labeling is changed - the "positive" samples are named "negative" and vice versa. This criticism is met by the P4 metric definition, which is sometimes indicated as a symmetrical extension of F1.

Difference from Fowlkes–Mallows index

While the F-measure is the harmonic mean of recall and precision, the Fowlkes–Mallows index is their geometric mean.

Extension to multi-class classification

The F-score is also used for evaluating classification problems with more than two classes (Multiclass classification). A common method is to average the F-score over each class, aiming at a balanced measurement of performance.

Macro F1

Macro F1 is a macro-averaged F1 score aiming at a balanced performance measurement. To calculate macro F1, two different averaging-formulas have been used: the F1 score of (arithmetic) class-wise precision and recall means or the arithmetic mean of class-wise F1 scores, where the latter exhibits more desirable properties.