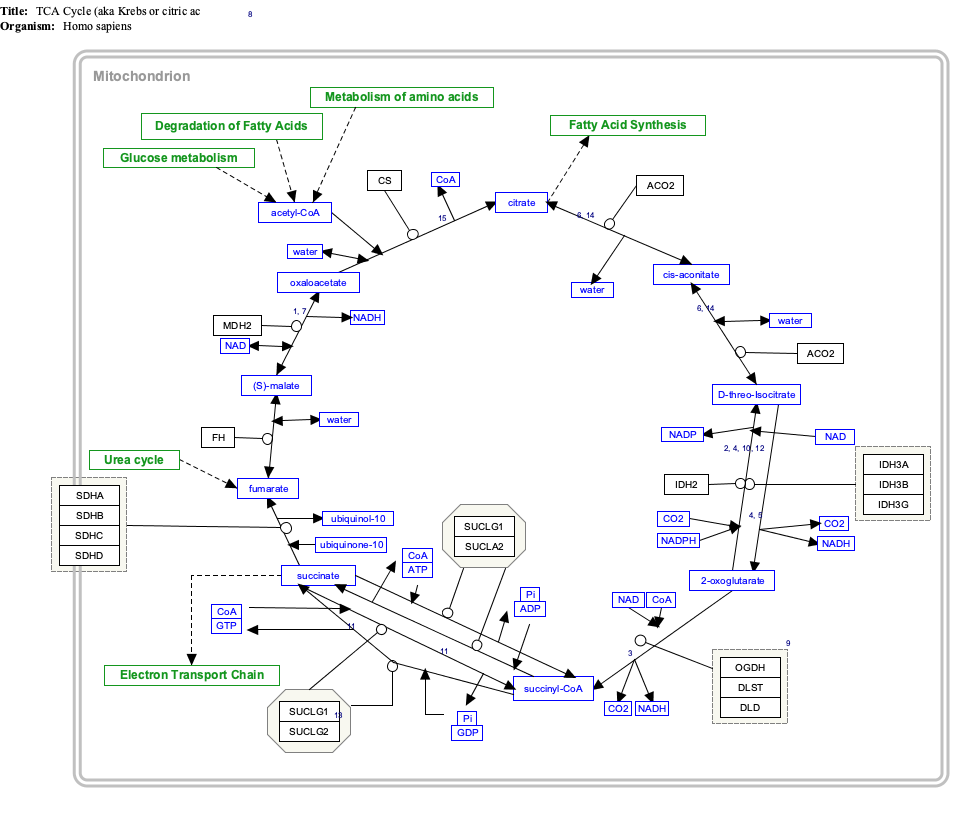

The citric acid cycle—also known as the Krebs cycle, Szent–Györgyi–Krebs cycle, or TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of biochemical reactions to release the energy stored in nutrients through the oxidation of acetyl-CoA derived from carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and alcohol. The chemical energy released is available in the form of ATP. The Krebs cycle is used by organisms that respire (as opposed to organisms that ferment) to generate energy, either by anaerobic respiration or aerobic respiration. In addition, the cycle provides precursors of certain amino acids, as well as the reducing agent NADH, that are used in numerous other reactions. Its central importance to many biochemical pathways suggests that it was one of the earliest components of metabolism. Even though it is branded as a "cycle", it is not necessary for metabolites to follow only one specific route; at least three alternative segments of the citric acid cycle have been recognized.

The name of this metabolic pathway is derived from the citric acid (a tricarboxylic acid, often called citrate, as the ionized form predominates at biological pH) that is consumed and then regenerated by this sequence of reactions to complete the cycle. The cycle consumes acetate (in the form of acetyl-CoA) and water, reduces NAD+ to NADH, releasing carbon dioxide. The NADH generated by the citric acid cycle is fed into the oxidative phosphorylation (electron transport) pathway. The net result of these two closely linked pathways is the oxidation of nutrients to produce usable chemical energy in the form of ATP.

In eukaryotic cells, the citric acid cycle occurs in the matrix of the mitochondrion. In prokaryotic cells, such as bacteria, which lack mitochondria, the citric acid cycle reaction sequence is performed in the cytosol with the proton gradient for ATP production being across the cell's surface (plasma membrane) rather than the inner membrane of the mitochondrion.

For each pyruvate molecule (from glycolysis), the overall yield of energy-containing compounds from the citric acid cycle is three NADH, one FADH2, and one GTP.

Discovery

Several of the components and reactions of the citric acid cycle were established in the 1930s by the research of Albert Szent-Györgyi, who received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1937 specifically for his discoveries pertaining to fumaric acid, a component of the cycle. He made this discovery by studying pigeon breast muscle. Because this tissue maintains its oxidative capacity well after breaking down in the Latapie mincer and releasing in aqueous solutions, breast muscle of the pigeon was very well qualified for the study of oxidative reactions. The citric acid cycle itself was finally identified in 1937 by Hans Adolf Krebs and William Arthur Johnson while at the University of Sheffield, for which the former received the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1953, and for whom the cycle is sometimes named the "Krebs cycle".

Overview

The citric acid cycle is a metabolic pathway that connects carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism. The reactions of the cycle are carried out by eight enzymes that completely oxidize acetate (a two carbon molecule), in the form of acetyl-CoA, into two molecules each of carbon dioxide and water. Through catabolism of sugars, fats, and proteins, the two-carbon organic product acetyl-CoA is produced which enters the citric acid cycle. The reactions of the cycle also convert three equivalents of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) into three equivalents of reduced NAD (NADH), one equivalent of flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) into one equivalent of FADH2, and one equivalent each of guanosine diphosphate (GDP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi) into one equivalent of guanosine triphosphate (GTP). The NADH and FADH2 generated by the citric acid cycle are, in turn, used by the oxidative phosphorylation pathway to generate energy-rich ATP.

One of the primary sources of acetyl-CoA is from the breakdown of sugars by glycolysis which yield pyruvate that in turn is decarboxylated by the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex generating acetyl-CoA according to the following reaction scheme:

The product of this reaction, acetyl-CoA, is the starting point for the citric acid cycle. Acetyl-CoA may also be obtained from the oxidation of fatty acids. Below is a schematic outline of the cycle:

- The citric acid cycle begins with the transfer of a two-carbon acetyl group from acetyl-CoA to the four-carbon acceptor compound (oxaloacetate) to form a six-carbon compound (citrate).

- The citrate then goes through a series of chemical transformations, losing two carboxyl groups as CO2. The carbons lost as CO2 originate from what was oxaloacetate, not directly from acetyl-CoA. The carbons donated by acetyl-CoA become part of the oxaloacetate carbon backbone after the first turn of the citric acid cycle. Loss of the acetyl-CoA-donated carbons as CO2 requires several turns of the citric acid cycle. However, because of the role of the citric acid cycle in anabolism, they might not be lost, since many citric acid cycle intermediates are also used as precursors for the biosynthesis of other molecules.

- Most of the electrons made available by the oxidative steps of the cycle are transferred to NAD+, forming NADH. For each acetyl group that enters the citric acid cycle, three molecules of NADH are produced. The citric acid cycle includes a series of redox reactions in mitochondria.

- In addition, electrons from the succinate oxidation step are transferred first to the FAD cofactor of succinate dehydrogenase, reducing it to FADH2, and eventually to ubiquinone (Q) in the mitochondrial membrane, reducing it to ubiquinol (QH2) which is a substrate of the electron transfer chain at the level of Complex III.

- For every NADH and FADH2 that are produced in the citric acid cycle, 2.5 and 1.5 ATP molecules are generated in oxidative phosphorylation, respectively.

- At the end of each cycle, the four-carbon oxaloacetate has been regenerated, and the cycle continues.

Steps

There are ten basic steps in the citric acid cycle, as outlined below. The cycle is continuously supplied with new carbon in the form of acetyl-CoA, entering at step 0 in the table.

|

|

Reaction type | Substrates | Enzyme | Products | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 / 10 | Aldol condensation | Oxaloacetate + Acetyl CoA + H2O | Citrate synthase | Citrate + CoA-SH | irreversible, extends the 4C oxaloacetate to a 6C molecule |

| 1 | Dehydration | Citrate | Aconitase | cis-Aconitate + H2O | reversible isomerisation |

| 2 | Hydration | cis-Aconitate + H2O | Isocitrate | ||

| 3 | Oxidation | Isocitrate + NAD+ | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | Oxalosuccinate + NADH + H + | generates NADH (equivalent of 2.5 ATP) |

| 4 | Decarboxylation | Oxalosuccinate | α-Ketoglutarate + CO2 | rate-limiting, irreversible stage, generates a 5C molecule | |

| 5 | Oxidative decarboxylation |

α-Ketoglutarate + NAD+ + CoA-SH | α-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, Thiamine pyrophosphate, Lipoic acid, Mg++,transsuccinytase |

Succinyl-CoA + NADH + H + + CO2 | irreversible stage, generates NADH (equivalent of 2.5 ATP), regenerates the 4C chain (CoA excluded) |

| 6 | substrate-level phosphorylation |

Succinyl-CoA + GDP + Pi | Succinyl-CoA synthetase | Succinate + CoA-SH + GTP | or ADP→ATP instead of GDP→GTP, generates 1 ATP or equivalent. Condensation reaction of GDP + Pi and hydrolysis of succinyl-CoA involve the H2O needed for balanced equation. |

| 7 | Oxidation | Succinate + ubiquinone (Q) | Succinate dehydrogenase | Fumarate + ubiquinol (QH2) | uses FAD as a prosthetic group (FAD→FADH2 in the first step of the reaction) in the enzyme. These two electrons are later transferred to QH2 during Complex II of the ETC, where they generate the equivalent of 1.5 ATP |

| 8 | Hydration | Fumarate + H2O | Fumarase | L-Malate | Hydration of C-C double bond |

| 9 | Oxidation | L-Malate + NAD+ | Malate dehydrogenase | Oxaloacetate + NADH + H+ | reversible (in fact, equilibrium favors malate), generates NADH (equivalent of 2.5 ATP) |

| 10 / 0 | Aldol condensation | Oxaloacetate + Acetyl CoA + H2O | Citrate synthase | Citrate + CoA-SH | This is the same as step 0 and restarts the cycle. The reaction is irreversible and extends the 4C oxaloacetate to a 6C molecule |

Two carbon atoms are oxidized to CO2, the energy from these reactions is transferred to other metabolic processes through GTP (or ATP), and as electrons in NADH and QH2. The NADH generated in the citric acid cycle may later be oxidized (donate its electrons) to drive ATP synthesis in a type of process called oxidative phosphorylation. FADH2 is covalently attached to succinate dehydrogenase, an enzyme which functions both in the citric acid cycle and the mitochondrial electron transport chain in oxidative phosphorylation. FADH2, therefore, facilitates transfer of electrons to coenzyme Q, which is the final electron acceptor of the reaction catalyzed by the succinate:ubiquinone oxidoreductase complex, also acting as an intermediate in the electron transport chain.

Mitochondria in animals, including humans, possess two succinyl-CoA synthetases: one that produces GTP from GDP, and another that produces ATP from ADP. Plants have the type that produces ATP (ADP-forming succinyl-CoA synthetase). Several of the enzymes in the cycle may be loosely associated in a multienzyme protein complex within the mitochondrial matrix.

The GTP that is formed by GDP-forming succinyl-CoA synthetase may be utilized by nucleoside-diphosphate kinase to form ATP (the catalyzed reaction is GTP + ADP → GDP + ATP).

Products

Products of the first turn of the cycle are one GTP (or ATP), three NADH, one FADH2 and two CO2.

Because two acetyl-CoA molecules are produced from each glucose molecule, two cycles are required per glucose molecule. Therefore, at the end of two cycles, the products are: two GTP, six NADH, two FADH2, and four CO2.

| Description | Reactants | Products |

|---|---|---|

| The sum of all reactions in the citric acid cycle is: | Acetyl-CoA + 3 NAD+ + FAD + GDP + Pi + 2 H2O | → CoA-SH + 3 NADH + FADH2 + 3 H+ + GTP + 2 CO2 |

| Combining the reactions occurring during the pyruvate oxidation with those occurring during the citric acid cycle, the following overall pyruvate oxidation reaction is obtained: | Pyruvate ion + 4 NAD+ + FAD + GDP + Pi + 2 H2O | → 4 NADH + FADH2 + 4 H+ + GTP + 3 CO2 |

| Combining the above reaction with the ones occurring in the course of glycolysis, the following overall glucose oxidation reaction (excluding reactions in the respiratory chain) is obtained: | Glucose + 10 NAD+ + 2 FAD + 2 ADP + 2 GDP + 4 Pi + 2 H2O | → 10 NADH + 2 FADH2 + 10 H+ + 2 ATP + 2 GTP + 6 CO2 |

The above reactions are balanced if Pi represents the H2PO4− ion, ADP and GDP the ADP2− and GDP2− ions, respectively, and ATP and GTP the ATP3− and GTP3− ions, respectively.

The total number of ATP molecules obtained after complete oxidation of one glucose in glycolysis, citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation is estimated to be between 30 and 38.

Efficiency

The theoretical maximum yield of ATP through oxidation of one molecule of glucose in glycolysis, citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation is 38 (assuming 3 molar equivalents of ATP per equivalent NADH and 2 ATP per FADH2). In eukaryotes, two equivalents of NADH and two equivalents of ATP are generated in glycolysis, which takes place in the cytoplasm. If transported using the glycerol phosphate shuttle rather than the malate–aspartate shuttle, transport of two of these equivalents of NADH into the mitochondria effectively consumes two equivalents of ATP, thus reducing the net production of ATP to 36. Furthermore, inefficiencies in oxidative phosphorylation due to leakage of protons across the mitochondrial membrane and slippage of the ATP synthase/proton pump commonly reduces the ATP yield from NADH and FADH2 to less than the theoretical maximum yield. The observed yields are, therefore, closer to ~2.5 ATP per NADH and ~1.5 ATP per FADH2, further reducing the total net production of ATP to approximately 30. An assessment of the total ATP yield with newly revised proton-to-ATP ratios provides an estimate of 29.85 ATP per glucose molecule.

Variation

While the citric acid cycle is in general highly conserved, there is significant variability in the enzymes found in different taxa (note that the diagrams on this page are specific to the mammalian pathway variant).

Some differences exist between eukaryotes and prokaryotes. The conversion of D-threo-isocitrate to 2-oxoglutarate is catalyzed in eukaryotes by the NAD+-dependent EC 1.1.1.41, while prokaryotes employ the NADP+-dependent EC 1.1.1.42.[23] Similarly, the conversion of (S)-malate to oxaloacetate is catalyzed in eukaryotes by the NAD+-dependent EC 1.1.1.37, while most prokaryotes utilize a quinone-dependent enzyme, EC 1.1.5.4.[24]

A step with significant variability is the conversion of succinyl-CoA to succinate. Most organisms utilize EC 6.2.1.5, succinate–CoA ligase (ADP-forming) (despite its name, the enzyme operates in the pathway in the direction of ATP formation). In mammals a GTP-forming enzyme, succinate–CoA ligase (GDP-forming) (EC 6.2.1.4) also operates. The level of utilization of each isoform is tissue dependent. In some acetate-producing bacteria, such as Acetobacter aceti, an entirely different enzyme catalyzes this conversion – EC 2.8.3.18, succinyl-CoA:acetate CoA-transferase. This specialized enzyme links the TCA cycle with acetate metabolism in these organisms. Some bacteria, such as Helicobacter pylori, employ yet another enzyme for this conversion – succinyl-CoA:acetoacetate CoA-transferase (EC 2.8.3.5).

Some variability also exists at the previous step – the conversion of 2-oxoglutarate to succinyl-CoA. While most organisms utilize the ubiquitous NAD+-dependent 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, some bacteria utilize a ferredoxin-dependent 2-oxoglutarate synthase (EC 1.2.7.3). Other organisms, including obligately autotrophic and methanotrophic bacteria and archaea, bypass succinyl-CoA entirely, and convert 2-oxoglutarate to succinate via succinate semialdehyde, using EC 4.1.1.71, 2-oxoglutarate decarboxylase, and EC 1.2.1.79, succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase.

In cancer

In cancer, there are substantial metabolic derangements that occur to ensure the proliferation of tumor cells, and consequently metabolites can accumulate which serve to facilitate tumorigenesis, dubbed oncometabolites. Among the best characterized oncometabolites is 2-hydroxyglutarate which is produced through a heterozygous gain-of-function mutation (specifically a neomorphic one) in isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) (which under normal circumstances catalyzes the oxidation of isocitrate to oxalosuccinate, which then spontaneously decarboxylates to alpha-ketoglutarate, as discussed above; in this case an additional reduction step occurs after the formation of alpha-ketoglutarate via NADPH to yield 2-hydroxyglutarate), and hence IDH is considered an oncogene. Under physiological conditions, 2-hydroxyglutarate is a minor product of several metabolic pathways as an error but readily converted to alpha-ketoglutarate via hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase enzymes (L2HGDH and D2HGDH) but does not have a known physiologic role in mammalian cells; of note, in cancer, 2-hydroxyglutarate is likely a terminal metabolite as isotope labelling experiments of colorectal cancer cell lines show that its conversion back to alpha-ketoglutarate is too low to measure. In cancer, 2-hydroxyglutarate serves as a competitive inhibitor for a number of enzymes that facilitate reactions via alpha-ketoglutarate in alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. This mutation results in several important changes to the metabolism of the cell. For one thing, because there is an extra NADPH-catalyzed reduction, this can contribute to depletion of cellular stores of NADPH and also reduce levels of alpha-ketoglutarate available to the cell. In particular, the depletion of NADPH is problematic because NADPH is highly compartmentalized and cannot freely diffuse between the organelles in the cell. It is produced largely via the pentose phosphate pathway in the cytoplasm. The depletion of NADPH results in increased oxidative stress within the cell as it is a required cofactor in the production of GSH, and this oxidative stress can result in DNA damage. There are also changes on the genetic and epigenetic level through the function of histone lysine demethylases (KDMs) and ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes; ordinarily TETs hydroxylate 5-methylcytosines to prime them for demethylation. However, in the absence of alpha-ketoglutarate this cannot be done and there is hence hypermethylation of the cell's DNA, serving to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and inhibit cellular differentiation. A similar phenomenon is observed for the Jumonji C family of KDMs which require a hydroxylation to perform demethylation at the epsilon-amino methyl group. Additionally, the inability of prolyl hydroxylases to catalyze reactions results in stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor alpha, which is necessary to promote degradation of the latter (as under conditions of low oxygen there will not be adequate substrate for hydroxylation). This results in a pseudohypoxic phenotype in the cancer cell that promotes angiogenesis, metabolic reprogramming, cell growth, and migration.

Regulation

Allosteric regulation by metabolites. The regulation of the citric acid cycle is largely determined by product inhibition and substrate availability. If the cycle were permitted to run unchecked, large amounts of metabolic energy could be wasted in overproduction of reduced coenzyme such as NADH and ATP. The major eventual substrate of the cycle is ADP which gets converted to ATP. A reduced amount of ADP causes accumulation of precursor NADH which in turn can inhibit a number of enzymes. NADH, a product of all dehydrogenases in the citric acid cycle with the exception of succinate dehydrogenase, inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, and also citrate synthase. Acetyl-coA inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase, while succinyl-CoA inhibits alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase and citrate synthase. When tested in vitro with TCA enzymes, ATP inhibits citrate synthase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase; however, ATP levels do not change more than 10% in vivo between rest and vigorous exercise. There is no known allosteric mechanism that can account for large changes in reaction rate from an allosteric effector whose concentration changes less than 10%.

Citrate is used for feedback inhibition, as it inhibits phosphofructokinase, an enzyme involved in glycolysis that catalyses formation of fructose 1,6-bisphosphate, a precursor of pyruvate. This prevents a constant high rate of flux when there is an accumulation of citrate and a decrease in substrate for the enzyme.

Regulation by calcium. Calcium is also used as a regulator in the citric acid cycle. Calcium levels in the mitochondrial matrix can reach up to the tens of micromolar levels during cellular activation. It activates pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase which in turn activates the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Calcium also activates isocitrate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. This increases the reaction rate of many of the steps in the cycle, and therefore increases flux throughout the pathway.

Transcriptional regulation. There is a link between intermediates of the citric acid cycle and the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF). HIF plays a role in the regulation of oxygen homeostasis, and is a transcription factor that targets angiogenesis, vascular remodeling, glucose utilization, iron transport and apoptosis. HIF is synthesized constitutively, and hydroxylation of at least one of two critical proline residues mediates their interaction with the von Hippel Lindau E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, which targets them for rapid degradation. This reaction is catalysed by prolyl 4-hydroxylases. Fumarate and succinate have been identified as potent inhibitors of prolyl hydroxylases, thus leading to the stabilisation of HIF.

Major metabolic pathways converging on the citric acid cycle

Several catabolic pathways converge on the citric acid cycle. Most of these reactions add intermediates to the citric acid cycle, and are therefore known as anaplerotic reactions, from the Greek meaning to "fill up". These increase the amount of acetyl CoA that the cycle is able to carry, increasing the mitochondrion's capability to carry out respiration if this is otherwise a limiting factor. Processes that remove intermediates from the cycle are termed "cataplerotic" reactions.

In this section and in the next, the citric acid cycle intermediates are indicated in italics to distinguish them from other substrates and end-products.

Pyruvate molecules produced by glycolysis are actively transported across the inner mitochondrial membrane, and into the matrix. Here they can be oxidized and combined with coenzyme A to form CO2, acetyl-CoA, and NADH, as in the normal cycle.

However, it is also possible for pyruvate to be carboxylated by pyruvate carboxylase to form oxaloacetate. This latter reaction "fills up" the amount of oxaloacetate in the citric acid cycle, and is therefore an anaplerotic reaction, increasing the cycle's capacity to metabolize acetyl-CoA when the tissue's energy needs (e.g. in muscle) are suddenly increased by activity.

In the citric acid cycle all the intermediates (e.g. citrate, iso-citrate, alpha-ketoglutarate, succinate, fumarate, malate, and oxaloacetate) are regenerated during each turn of the cycle. Adding more of any of these intermediates to the mitochondrion therefore means that that additional amount is retained within the cycle, increasing all the other intermediates as one is converted into the other. Hence the addition of any one of them to the cycle has an anaplerotic effect, and its removal has a cataplerotic effect. These anaplerotic and cataplerotic reactions will, during the course of the cycle, increase or decrease the amount of oxaloacetate available to combine with acetyl-CoA to form citric acid. This in turn increases or decreases the rate of ATP production by the mitochondrion, and thus the availability of ATP to the cell.

Acetyl-CoA, on the other hand, derived from pyruvate oxidation, or from the beta-oxidation of fatty acids, is the only fuel to enter the citric acid cycle. With each turn of the cycle one molecule of acetyl-CoA is consumed for every molecule of oxaloacetate present in the mitochondrial matrix, and is never regenerated. It is the oxidation of the acetate portion of acetyl-CoA that produces CO2 and water, with the energy thus released captured in the form of ATP. The three steps of beta-oxidation resemble the steps that occur in the production of oxaloacetate from succinate in the TCA cycle. Acyl-CoA is oxidized to trans-Enoyl-CoA while FAD is reduced to FADH2, which is similar to the oxidation of succinate to fumarate. Following, trans-enoyl-CoA is hydrated across the double bond to beta-hydroxyacyl-CoA, just like fumarate is hydrated to malate. Lastly, beta-hydroxyacyl-CoA is oxidized to beta-ketoacyl-CoA while NAD+ is reduced to NADH, which follows the same process as the oxidation of malate to oxaloacetate.

In the liver, the carboxylation of cytosolic pyruvate into intra-mitochondrial oxaloacetate is an early step in the gluconeogenic pathway which converts lactate and de-aminated alanine into glucose, under the influence of high levels of glucagon and/or epinephrine in the blood. Here the addition of oxaloacetate to the mitochondrion does not have a net anaplerotic effect, as another citric acid cycle intermediate (malate) is immediately removed from the mitochondrion to be converted into cytosolic oxaloacetate, which is ultimately converted into glucose, in a process that is almost the reverse of glycolysis.

In protein catabolism, proteins are broken down by proteases into their constituent amino acids. Their carbon skeletons (i.e. the de-aminated amino acids) may either enter the citric acid cycle as intermediates (e.g. alpha-ketoglutarate derived from glutamate or glutamine), having an anaplerotic effect on the cycle, or, in the case of leucine, isoleucine, lysine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine, they are converted into acetyl-CoA which can be burned to CO2 and water, or used to form ketone bodies, which too can only be burned in tissues other than the liver where they are formed, or excreted via the urine or breath. These latter amino acids are therefore termed "ketogenic" amino acids, whereas those that enter the citric acid cycle as intermediates can only be cataplerotically removed by entering the gluconeogenic pathway via malate which is transported out of the mitochondrion to be converted into cytosolic oxaloacetate and ultimately into glucose. These are the so-called "glucogenic" amino acids. De-aminated alanine, cysteine, glycine, serine, and threonine are converted to pyruvate and can consequently either enter the citric acid cycle as oxaloacetate (an anaplerotic reaction) or as acetyl-CoA to be disposed of as CO2 and water.

In fat catabolism, triglycerides are hydrolyzed to break them into fatty acids and glycerol. In the liver the glycerol can be converted into glucose via dihydroxyacetone phosphate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate by way of gluconeogenesis. In skeletal muscle, glycerol is used in glycolysis by converting glycerol into glycerol-3-phosphate, then into dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), then into glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate.

In many tissues, especially heart and skeletal muscle tissue, fatty acids are broken down through a process known as beta oxidation, which results in the production of mitochondrial acetyl-CoA, which can be used in the citric acid cycle. Beta oxidation of fatty acids with an odd number of methylene bridges produces propionyl-CoA, which is then converted into succinyl-CoA and fed into the citric acid cycle as an anaplerotic intermediate.

The total energy gained from the complete breakdown of one (six-carbon) molecule of glucose by glycolysis, the formation of 2 acetyl-CoA molecules, their catabolism in the citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation equals about 30 ATP molecules, in eukaryotes. The number of ATP molecules derived from the beta oxidation of a 6 carbon segment of a fatty acid chain, and the subsequent oxidation of the resulting 3 molecules of acetyl-CoA is 40.

Citric acid cycle intermediates serve as substrates for biosynthetic processes

In this subheading, as in the previous one, the TCA intermediates are identified by italics.

Several of the citric acid cycle intermediates are used for the synthesis of important compounds, which will have significant cataplerotic effects on the cycle. Acetyl-CoA cannot be transported out of the mitochondrion. To obtain cytosolic acetyl-CoA, citrate is removed from the citric acid cycle and carried across the inner mitochondrial membrane into the cytosol. There it is cleaved by ATP citrate lyase into acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate. The oxaloacetate is returned to mitochondrion as malate (and then converted back into oxaloacetate to transfer more acetyl-CoA out of the mitochondrion). The cytosolic acetyl-CoA is used for fatty acid synthesis and the production of cholesterol. Cholesterol can, in turn, be used to synthesize the steroid hormones, bile salts, and vitamin D.

The carbon skeletons of many non-essential amino acids are made from citric acid cycle intermediates. To turn them into amino acids the alpha keto-acids formed from the citric acid cycle intermediates have to acquire their amino groups from glutamate in a transamination reaction, in which pyridoxal phosphate is a cofactor. In this reaction the glutamate is converted into alpha-ketoglutarate, which is a citric acid cycle intermediate. The intermediates that can provide the carbon skeletons for amino acid synthesis are oxaloacetate which forms aspartate and asparagine; and alpha-ketoglutarate which forms glutamine, proline, and arginine.

Of these amino acids, aspartate and glutamine are used, together with carbon and nitrogen atoms from other sources, to form the purines that are used as the bases in DNA and RNA, as well as in ATP, AMP, GTP, NAD, FAD and CoA.

The pyrimidines are partly assembled from aspartate (derived from oxaloacetate). The pyrimidines, thymine, cytosine and uracil, form the complementary bases to the purine bases in DNA and RNA, and are also components of CTP, UMP, UDP and UTP.

The majority of the carbon atoms in the porphyrins come from the citric acid cycle intermediate, succinyl-CoA. These molecules are an important component of the hemoproteins, such as hemoglobin, myoglobin and various cytochromes.

During gluconeogenesis mitochondrial oxaloacetate is reduced to malate which is then transported out of the mitochondrion, to be oxidized back to oxaloacetate in the cytosol. Cytosolic oxaloacetate is then decarboxylated to phosphoenolpyruvate by phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, which is the rate limiting step in the conversion of nearly all the gluconeogenic precursors (such as the glucogenic amino acids and lactate) into glucose by the liver and kidney.

Because the citric acid cycle is involved in both catabolic and anabolic processes, it is known as an amphibolic pathway. Evan M.W.Duo Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles.

Glucose feeds the TCA cycle via circulating lactate

The metabolic role of lactate is well recognized as a fuel for tissues, mitochondrial cytopathies such as DPH Cytopathy, and the scientific field of oncology (tumors). In the classical Cori cycle, muscles produce lactate which is then taken up by the liver for gluconeogenesis. New studies suggest that lactate can be used as a source of carbon for the TCA cycle.