An IBM PC compatible is any personal computer that is hardware- and software-compatible with the IBM Personal Computer (IBM PC) and its subsequent models. Like the original IBM PC, an IBM PC–compatible computer uses an x86-based central processing unit, sourced either from Intel or a second source like AMD, Cyrix or other vendors such as Texas Instruments, Fujitsu, OKI, Mitsubishi or NEC and is capable of using interchangeable commodity hardware such as expansion cards. Initially such computers were referred to as PC clones, IBM clones or IBM PC clones, but the term "IBM PC compatible" is now a historical description only, as the vast majority of microcomputers produced since the 1990s are IBM compatible. IBM itself no longer sells personal computers, having sold its division to Lenovo in 2005. "Wintel" is a similar description that is more commonly used for modern computers.

The designation "PC", as used in much of personal computer history, has not meant "personal computer" generally, but rather an x86 computer capable of running the same software that a contemporary IBM or Lenovo PC could. The term was initially in contrast to the variety of home computer systems available in the early 1980s, such as the Apple II, TRS-80, and Commodore 64. Later, the term was primarily used in contrast to Commodore's Amiga and Apple's Macintosh computers.

Overview

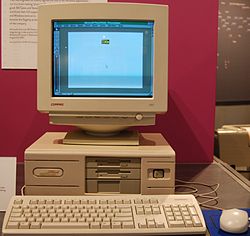

These "clones" duplicated almost all the significant features of the original IBM PC architectures. This was facilitated by IBM's choice of commodity hardware components, which were cheap, and by various manufacturers' ability to reverse-engineer the BIOS firmware using a "clean room design" technique. Columbia Data Products built the first clone of the IBM personal computer, the MPC 1600 by a clean-room reverse-engineered implementation of its BIOS. Other rival companies, Corona Data Systems, Eagle Computer, and the Handwell Corporation were threatened with legal action by IBM, who settled with them. Soon after in 1982, Compaq released the very successful Compaq Portable, also with a clean-room reverse-engineered BIOS, and also not challenged legally by IBM.

Early IBM PC compatibles used the same computer buses as their IBM counterparts, switching from the 8-bit IBM PC and XT bus to the 16-bit IBM AT bus with the release of the AT. IBM's introduction of the proprietary Micro Channel architecture (MCA) in its Personal System/2 (PS/2) series resulted in the establishment of the Extended Industry Standard Architecture bus open standard by a consortium of IBM PC compatible vendors, redefining the 16-bit IBM AT bus as the Industry Standard Architecture (ISA) bus. Additional bus standards were subsequently adopted to improve compatibility between IBM PC compatibles, including the VESA Local Bus (VLB), Peripheral Component Interconnect (PCI), and the Accelerated Graphics Port (AGP).

Descendants of the x86 IBM PC compatibles, namely 64-bit computers based on "x86-64/AMD64" chips comprise the majority of desktop computers on the market as of 2021, with the dominant operating system being Microsoft Windows. Interoperability with the bus structure and peripherals of the original PC architecture may be limited or non-existent. Many modern computers are unable to use old software or hardware that depends on portions of the IBM PC compatible architecture which are missing or do not have equivalents in modern computers. For example, computers which boot using Unified Extensible Firmware Interface-based firmware that lack a Compatibility Support Module, or CSM, required to emulate the old BIOS-based firmware interface, or have their CSMs disabled, cannot natively run MS-DOS since MS-DOS depends on a BIOS interface to boot.

Only the Macintosh had kept significant market share without having compatibility with the IBM PC, except in the period between the transition to Intel processors and transition to Apple silicon, when Macs used standard PC components and were capable of dual-booting Windows with Boot Camp.

Origins

IBM decided in 1980 to market a low-cost single-user computer as quickly as possible. On August 12, 1981, the first IBM PC went on sale. There were three operating systems (OS) available for it. The least expensive and most popular was PC DOS made by Microsoft. In a crucial concession, IBM's agreement allowed Microsoft to sell its own version, MS-DOS, for non-IBM computers. The only component of the original PC architecture exclusive to IBM was the BIOS (Basic Input/Output System).

IBM at first asked developers to avoid writing software that addressed the computer's hardware directly and to instead make standard calls to BIOS functions that carried out hardware-dependent operations. This software would run on any machine using MS-DOS or PC DOS. Software that directly addressed the hardware instead of making standard calls was faster, however; this was particularly relevant to games. Software addressing IBM PC hardware in this way would not run on MS-DOS machines with different hardware (for example, the PC-98). The IBM PC was sold in high enough volumes to justify writing software specifically for it, and this encouraged other manufacturers to produce machines that could use the same programs, expansion cards, and peripherals as the PC. The x86 computer marketplace rapidly excluded all machines which were not hardware-compatible or software-compatible with the PC. The 640 KB barrier on "conventional" system memory available to MS-DOS is a legacy of that period; other non-clone machines, while subject to a limit, could exceed 640 KB.

Rumors of "lookalike," compatible computers, created without IBM's approval, began almost immediately after the IBM PC's release. InfoWorld wrote on the first anniversary of the IBM PC that

The dark side of an open system is its imitators. If the specs are clear enough for you to design peripherals, they are clear enough for you to design imitations. Apple ... has patents on two important components of its systems ... IBM, which reportedly has no special patents on the PC, is even more vulnerable. Numerous PC-compatible machines—the grapevine says 60 or more—have begun to appear in the marketplace.

By June 1983 PC Magazine defined "PC 'clone'" as "a computer [that can] accommodate the user who takes a disk home from an IBM PC, walks across the room, and plugs it into the 'foreign' machine".[7] Demand for the PC by then was so strong that dealers received 60% or less of the inventory they wanted, and many customers purchased clones instead. Columbia Data Products produced the first computer more or less compatible with the IBM PC standard during June 1982, soon followed by Eagle Computer. Compaq announced its first product, an IBM PC compatible in November 1982, the Compaq Portable. The Compaq was the first sewing machine-sized portable computer that was essentially 100% PC-compatible. The court decision in Apple v. Franklin, was that BIOS code was protected by copyright law, but it could reverse-engineer the IBM BIOS and then write its own BIOS using clean room design. Note this was over a year after Compaq released the Portable. The money and research put into reverse-engineering the BIOS was a calculated risk.

Compatibility issues

Non-compatible MS-DOS computers: Workalikes

At the same time, many manufacturers such as Tandy/RadioShack, Xerox, Hewlett-Packard, Digital Equipment Corporation, Sanyo, Texas Instruments, Tulip, Wang and Olivetti introduced personal computers that supported MS-DOS, but were not completely software- or hardware-compatible with the IBM PC.

Tandy described the Tandy 2000, for example, as having a "'next generation' true 16-bit CPU", and with "More speed. More disk storage. More expansion" than the IBM PC or "other MS-DOS computers". While admitting in 1984 that many PC DOS programs did not work on the computer, the company stated that "the most popular, sophisticated software on the market" was available, either immediately or "over the next six months".

Like IBM, Microsoft's apparent intention was that application writers would write to the application programming interfaces in MS-DOS or the firmware BIOS, and that this would form what would now be termed a hardware abstraction layer. Each computer would have its own Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) version of MS-DOS, customized to its hardware. Any software written for MS-DOS would operate on any MS-DOS computer, despite variations in hardware design.

This expectation seemed reasonable in the computer marketplace of the time. Until then Microsoft's business was based primarily on computer languages such as BASIC. The established small system operating software was CP/M from Digital Research which was in use both at the hobbyist level and by the more professional of those using microcomputers. To achieve such widespread use, and thus make the product viable economically, the OS had to operate across a range of machines from different vendors that had widely varying hardware. Those customers who needed other applications than the starter programs could reasonably expect publishers to offer their products for a variety of computers, on suitable media for each.

Microsoft's competing OS was intended initially to operate on a similar varied spectrum of hardware, although all based on the 8086 processor. Thus, MS-DOS was for several years sold only as an OEM product. There was no Microsoft-branded MS-DOS: MS-DOS could not be purchased directly from Microsoft, and each OEM release was packaged with the trade dress of the given PC vendor. Malfunctions were to be reported to the OEM, not to Microsoft. However, as machines that were compatible with IBM hardware—thus supporting direct calls to the hardware—became widespread, it soon became clear that the OEM versions of MS-DOS were virtually identical, except perhaps for the provision of a few utility programs.

MS-DOS provided adequate functionality for character-oriented applications such as those that could have been implemented on a text-only terminal. Had the bulk of commercially important software been of this nature, low-level hardware compatibility might not have mattered. However, in order to provide maximum performance and leverage hardware features (or work around hardware bugs), PC applications quickly developed beyond the simple terminal applications that MS-DOS supported directly. Spreadsheets, WYSIWYG word processors, presentation software and remote communication software established new markets that exploited the PC's strengths, but required capabilities beyond what MS-DOS provided. Thus, from very early in the development of the MS-DOS software environment, many significant commercial software products were written directly to the hardware, for a variety of reasons:

- MS-DOS itself did not provide any way to position the text cursor other than to advance it after displaying each letter (teletype mode). While the BIOS video interface routines were adequate for rudimentary output, they were necessarily less efficient than direct hardware addressing, as they added extra processing; they did not have "string" output, but only character-by-character teletype output, and they inserted delays to prevent CGA hardware "snow" (a display artifact of CGA cards produced when writing directly to screen memory)——an especially bad artifact since they were called by IRQs, thus making multitasking very difficult. A program that wrote directly to video memory could achieve output rates 5 to 20 times faster than making system calls. Turbo Pascal used this technique from its earliest versions.

- Graphics capability was not taken seriously in the original IBM design brief; graphics were considered only from the perspective of generating static business graphics such as charts and graphs. MS-DOS did not have an API for graphics, and the BIOS only included the rudimentary graphics functions such as changing screen modes and plotting single points. To make a BIOS call for every point drawn or modified increased overhead considerably, making the BIOS interface notoriously slow. Because of this, line-drawing, arc-drawing, and blitting had to be performed by the application to achieve acceptable speed, which was usually done by bypassing the BIOS and accessing video memory directly. Software written to address IBM PC hardware directly would run on any IBM clone, but would have to be rewritten especially for each non-PC-compatible MS-DOS machine.

- Video games, even early ones, mostly required a true graphics mode. They also performed any machine-dependent trick the programmers could think of in order to gain speed. Though initially the major market for the PC was for business applications, games capability became an important factor motivating PC purchases as prices decreased. The availability and quality of games could mean the difference between the purchase of a PC compatible or a different platform with the ability to exchange data like the Amiga.

- Communications software directly accessed the UART serial port chip, because the MS-DOS API and the BIOS did not provide full support and was too slow to keep up with hardware which could transfer data at 19,200 bit/s.

- Even for standard business applications, speed of execution was a significant competitive advantage. Integrated software Context MBA preceded Lotus 1-2-3 to market and included more functions. Context MBA was written in UCSD p-System, making it very portable but too slow to be truly usable on a PC. 1-2-3 was written in x86 assembly language and performed some machine-dependent tricks. It was so much faster that it quickly surpassed Context MBA's sales.

- Disk copy-protection schemes, in common use at the time, worked by reading nonstandard data patterns on the diskette to verify originality. These patterns were impossible to detect using standard DOS or BIOS calls, so direct access to the disk controller hardware was necessary for the protection to work.

- Some software was designed to run only on a true IBM PC, and checked for an actual IBM BIOS.

First-generation PC workalikes by IBM competitors

| Computer name | Manufacturer | Date introduced | CPU | clock rate | Max RAM | Floppy disk capacity | Notable features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperion | Dynalogic | Jan 1983 | 8088 | 4.77 MHz | 640 KB | 320 KB | Canadian, license but never sold by Commodore |

| Olivetti M24/AT&T 6300 / Logabax Persona 1600 | Olivetti, marketed by AT&T | 1983 (AT&T 6300 June 1984) | 8086 | 8 MHz (later 10 MHz) | 640 KB | 360 KB (later 720 KB) | true IBM compatible;optional 640x400 color graphics |

| Zenith Z-100 | Zenith Data Systems | June 1982 | 8088 | 4.77 MHz | 768 KB | 360 KB | optional 8 color 640x255 graphics, external 8" floppy drives |

| HP-150 | Hewlett-Packard | Nov 1983 | 8088 | 8 MHz | 640 KB | 270 KB (later 710 KB) | primitive touchscreen |

| Compaq Portable | Compaq | Jan 1983 | 8088 | 4.77 MHz | 640 KB | 360 KB | sold as a true IBM compatible |

| Compaq Deskpro | Compaq | 1984 | 8086 | 8 MHz | 640 KB | 360 KB | sold as true IBM XT compatible |

| MPC 1600 | Columbia Data Products | June 1982 | 8088 | 4.77 MHz | 640 KB | 360 KB | true IBM compatible, credited as first PC clone |

| Eagle PC / 1600 series | Eagle Computer | 1982 | 8086 | 4.77 MHz | 640 KB | 360 KB | 750×352 mono graphics, first 8086 CPU |

| TI Professional Computer | Texas Instruments | Jan 1983 | 8088 | 5 MHz | 256 KB | 320 KB | 720x300 color graphics |

| DEC Rainbow | Digital Equipment Corporation | 1982 | 8088 | 4.81 MHz | 768 KB | 400 KB | 132x24 text mode, 8088 and Z80 CPUs |

| Wang PC | Wang Laboratories | Aug 1985 | 8086 | 8 MHz | 512 KB | 360 KB | 800x300 mono graphics |

| MBC-550 | Sanyo | 1982 | 8088 | 3.6 MHz | 256 KB | 360 KB (later 720 KB) | 640x200 8 color graphics (R, G, B bitplanes) |

| Apricot PC | Apricot Computers | 1983 | 8086 | 4.77 MHz | 768 KB | 720 KB | 800x400 mono graphics, 132x50 text mode |

| TS-1603 | TeleVideo | Apr 1983 | 8088 | 4.77 MHz | 256 KB | 737 KB | keyboard had palm rests, 16 function keys; built-in modem |

| Tava PC | Tava Corporation | Oct 1983 | 8088 | 4.77 MHz | 640 KB | 360 KB | true IBM compatible, credited as first private-label clone sold by manufacturer's stores |

| Tandy 2000 | Tandy Corporation | Sep 1983 | 80186 | 8 MHz | 768 KB | 720 KB | redefinable character set, optional 640x400 8-color or mono graphics |

"Operationally Compatible"

The first thing to think about when considering an IBM-compatible computer is, "How compatible is it?"

— BYTE, September 1983

In May 1983, Future Computing defined four levels of compatibility:

- Operationally Compatible. Can run "the top selling" IBM PC software, use PC expansion boards, and read and write PC disks. Has "complementary features" like portability or lower price that distinguish computer from the PC, which is sold in the same store. Examples: (Best) Columbia Data Products, Compaq; (Better) Corona; (Good) Eagle.

- Functionally Compatible. Runs own version of popular PC software. Cannot use PC expansion boards but can read and write PC disks. Cannot become Operationally Compatible. Example: TI Professional.

- Data Compatible. May not run top PC software. Can read and/or write PC disks. Can become Functionally Compatible. Examples: NCR Decision Mate, Olivetti M20, Wang PC, Zenith Z-100.

- Incompatible. Cannot read PC disks. Can become Data Compatible. Examples: Altos 586, DEC Rainbow 100, Grid Compass, Victor 9000.

During development, Compaq engineers found that Microsoft Flight Simulator would not run because of what subLOGIC's Bruce Artwick described as "a bug in one of Intel's chips", forcing them to make their new computer bug compatible with the IBM PC. At first, few clones other than Compaq's offered truly full compatibility. Jerry Pournelle purchased an IBM PC in mid-1983, "rotten keyboard and all", because he had "four cubic feet of unevaluated software, much of which won't run on anything but an IBM PC. Although a lot of machines claim to be 100 percent IBM PC compatible, I've yet to have one arrive ... Alas, a lot of stuff doesn't run with Eagle, Z-100, Compupro, or anything else we have around here". Columbia Data Products's November 1983 sales brochure stated that during tests with retail-purchased computers in October 1983, its own and Compaq's products were compatible with all tested PC software, while Corona and Eagle's were less compatible. Columbia University reported in January 1984 that Kermit ran without modification on Compaq and Columbia Data Products clones, but not on those from Eagle or Seequa. Other MS-DOS computers also required custom code.

By December 1983 Future Computing stated that companies like Compaq, Columbia Data Products, and Corona that emphasized IBM PC compatibility had been successful, while non-compatible computers had hurt the reputations of others like TI and DEC despite superior technology. At a San Francisco meeting it warned 200 attendees, from many American and foreign computer companies as well as IBM itself, to "Jump on the IBM PC-compatible bandwagon—quickly, and as compatibly as possible". Future Computing said in February 1984 that some computers were "press-release compatible", exaggerating their actual compatibility with the IBM PC. Many companies were reluctant to have their products' PC compatibility tested. When PC Magazine requested samples from computer manufacturers that claimed to produce compatibles for an April 1984 review, 14 of 31 declined.Corona specified that "Our systems run all software that conforms to IBM PC programming standards. And the most popular software does." When a BYTE journalist asked to test Peachtext at the Spring 1983 COMDEX, Corona representatives "hemmed and hawed a bit, but they finally led me ... off in the corner where no one would see it should it fail". The magazine reported that "Their hesitancy was unnecessary. The disk booted up without a problem". Zenith Data Systems was bolder, bragging that its Z-150 ran all applications people brought to test with at the 1984 West Coast Computer Faire.

Creative Computing in 1985 stated, "we reiterate our standard line regarding the IBM PC compatibles: try the package you want to use before you buy the computer." Companies modified their computers' BIOS to work with newly discovered incompatible applications, and reviewers and users developed stress tests to measure compatibility; by 1984 the ability to operate Lotus 1-2-3 and Flight Simulator became the standard, with compatibles specifically designed to run them and prominently advertising their compatibility.

IBM believed that some companies such as Eagle, Corona, and Handwell infringed on its copyright, and after Apple Computer, Inc. v. Franklin Computer Corp. successfully forced the clone makers to stop using the BIOS. The Phoenix BIOS in 1984, however, and similar products such as AMI BIOS, permitted computer makers to legally build essentially 100%-compatible clones without having to reverse-engineer the PC BIOS themselves. A September 1985 InfoWorld chart listed seven compatibles with 256 KB RAM, two disk drives, and monochrome monitors for $1,495 to $2,320, while the equivalent IBM PC cost $2,820. The Zenith Z-150 and inexpensive Leading Edge Model D are even compatible with IBM proprietary diagnostic software, unlike the Compaq Portable. By 1986 Compute! stated that "clones are generally reliable and about 99 percent compatible", and a 1987 survey in the magazine of the clone industry did not mention software compatibility, stating that "PC by now has come to stand for a computer capable of running programs that are managed by MS-DOS".

The decreasing influence of IBM

The main reason why an IBM standard is not worrying is that it can help competition to flourish. IBM will soon be as much a prisoner of its standards as its competitors are. Once enough IBM machines have been bought, IBM cannot make sudden changes in their basic design; what might be useful for shedding competitors would shake off even more customers.

— The Economist, November 1983

In February 1984 Byte wrote that "IBM's burgeoning influence in the PC community is stifling innovation because so many other companies are mimicking Big Blue", but The Economist stated in November 1983, "The main reason why an IBM standard is not worrying is that it can help competition to flourish".

By 1983, IBM had about 25% of sales of personal computers between $1,000 and $10,000, and computers with some PC compatibility were another 25%. As the market and competition grew IBM's influence diminished. Writing that even "IBM has to continue to be IBM compatible", in November 1985 PC Magazine stated "Now that it has created the [PC] market, the market doesn't necessarily need IBM for the machines. It may depend on IBM to set standards and to develop higher-performance machines, but IBM had better conform to existing standards so as to not hurt users". Observers noted IBM's silence when the industry that year quickly adopted the expanded memory standard, created by Lotus and Intel without IBM's participation. In January 1987, Bruce Webster wrote in Byte of rumors that IBM would introduce proprietary personal computers with a proprietary operating system: "Who cares? If IBM does it, they will most likely just isolate themselves from the largest marketplace, in which they really can't compete anymore anyway". He predicted that in 1987 the market "will complete its transition from an IBM standard to an Intel/MS-DOS/expansion bus standard ... Folks aren't so much concerned about IBM compatibility as they are about Lotus 1-2-3 compatibility". By 1992, Macworld stated that because of clones, "IBM lost control of its own market and became a minor player with its own technology".

The Economist predicted in 1983 that "IBM will soon be as much a prisoner of its standards as its competitors are", because "Once enough IBM machines have been bought, IBM cannot make sudden changes in their basic design; what might be useful for shedding competitors would shake off even more customers". After the Compaq Deskpro 386 became the first 80386-based PC, PC wrote that owners of the new computer did not need to fear that future IBM products would be incompatible with the Compaq, because such changes would also affect millions of real IBM PCs: "In sticking it to the competition, IBM would be doing the same to its own people". After IBM announced the OS/2-oriented PS/2 line in early 1987, sales of existing DOS-compatible PC compatibles rose, in part because the proprietary operating system was not available. In 1988, Gartner Group estimated that the public purchased 1.5 clones for every IBM PC. By 1989 Compaq was so influential that industry executives spoke of "Compaq compatible", with observers stating that customers saw the company as IBM's equal or superior. A 1990 American Institute of Certified Public Accountants member survey found that 23% of respondents used IBM computer hardware, and 16% used Compaq.

After 1987, IBM PC compatibles dominated both the home and business markets of commodity computers, with other notable alternative architectures being used in niche markets, like the Macintosh computers offered by Apple Inc. and used mainly for desktop publishing at the time, the aging 8-bit Commodore 64 which was selling for $150 by this time and became the world's bestselling computer, the 32-bit Commodore Amiga line used for television and video production and the 32-bit Atari ST used by the music industry. However, IBM itself lost the main role in the market for IBM PC compatibles by 1990. A few events in retrospect are important:

- IBM designed the PC with an open architecture which permitted clone makers to use freely available non-proprietary components.

- Microsoft included a clause in its contract with IBM which permitted the sale of the finished PC operating system (PC DOS) to other computer manufacturers. These IBM competitors licensed it, as MS-DOS, in order to offer PC compatibility for less cost.

- The 1982 introduction of the Columbia Data Products MPC 1600, the first 100% IBM PC compatible computer.

- The 1983 introduction of the Compaq Portable, providing portability unavailable from IBM at the time.

- An Independent Business Unit (IBU) within IBM developed the IBM PC and XT. IBUs did not share in corporate R&D expense. After the IBU became the Entry Systems Division it lost this benefit, greatly decreasing margins.

- The availability by 1986 of sub-$1,000 "Turbo XT" PC XT compatibles, including early offerings from Dell Computer, reducing demand for IBM's models. It was possible to buy two of these "generic" systems for less than the cost of one IBM-branded PC AT, and many companies did just that.

- By integrating more peripherals into the computer itself, compatibles like the Model D have more free ISA slots than the PC.

- Compaq was the first to release an Intel 80386-based computer, almost a year before IBM, with the Compaq Deskpro 386. Bill Gates later said that it was "the first time people started to get a sense that it wasn't just IBM setting the standards".

- IBM's 1987 introduction of the incompatible and proprietary MicroChannel Architecture (MCA) computer bus, for its Personal System/2 (PS/2) line.

- The split of the IBM-Microsoft partnership in development of OS/2. Tensions caused by the market success of Windows 3.0 ruptured the joint effort because IBM was committed to the 286's protected mode, which stunted OS/2's technical potential. Windows could take full advantage of the modern and increasingly affordable 386 / 386SX architecture. As well, there were cultural differences between the partners, and Windows was often bundled with new computers while OS/2 was only available for extra cost. The split left IBM the sole steward of OS/2 and it failed to keep pace with Windows.

- The 1988 introduction by the "Gang of Nine" companies of a rival bus, Extended Industry Standard Architecture, intended to compete with, rather than copy, MCA.

- The duelling expanded memory (EMS) and extended memory (XMS) standards of the late 1980s, both developed without input from IBM.

Despite popularity of its ThinkPad set of laptop PC's, IBM finally relinquished its role as a consumer PC manufacturer during April 2005, when it sold its laptop and desktop PC divisions (ThinkPad/ThinkCentre) to Lenovo for US$1.75 billion.

As of October 2007, Hewlett-Packard and Dell had the largest shares of the PC market in North America. They were also successful overseas, with Acer, Lenovo, and Toshiba also notable. Worldwide, a huge number of PCs are "white box" systems assembled by myriad local systems builders. Despite advances of computer technology, the IBM PC compatibles remained very much compatible with the original IBM PC computers, although most of the components implement the compatibility in special backward compatibility modes used only during a system boot. It was often more practical to run old software on a modern system using an emulator rather than relying on these features.

In 2014 Lenovo acquired IBM's x86-based server (System x) business for US$2.1 billion.

Expandability

One of the strengths of the PC-compatible design is its modular hardware design. End-users could readily upgrade peripherals and, to some degree, processor and memory without modifying the computer's motherboard or replacing the whole computer, as was the case with many of the microcomputers of the time. However, as processor speed and memory width increased, the limits of the original XT/AT bus design were soon reached, particularly when driving graphics video cards. IBM did introduce an upgraded bus in the IBM PS/2 computer that overcame many of the technical limits of the XT/AT bus, but this was rarely used as the basis for IBM-compatible computers since it required license payments to IBM both for the PS/2 bus and any prior AT-bus designs produced by the company seeking a license. This was unpopular with hardware manufacturers and several competing bus standards were developed by consortiums, with more agreeable license terms. Various attempts to standardize the interfaces were made, but in practice, many of these attempts were either flawed or ignored. Even so, there were many expansion options, and despite the confusion of its users, the PC compatible design advanced much faster than other competing designs of the time, even if only because of its market dominance.

"IBM PC compatible" becomes "Wintel"

During the 1990s, IBM's influence on PC architecture started to decline. "IBM PC compatible" becomes "Standard PC" in 1990s, and later "ACPI PC" in 2000s. An IBM-brand PC became the exception rather than the rule. Instead of placing importance on compatibility with the IBM PC, vendors began to emphasize compatibility with Windows. In 1993, a version of Windows NT was released that could operate on processors other than the x86 set. While it required that applications be recompiled, which most developers did not do, its hardware independence was used for Silicon Graphics (SGI) x86 workstations–thanks to NT's Hardware abstraction layer (HAL), they could operate NT (and its vast application library).

No mass-market personal computer hardware vendor dared to be incompatible with the latest version of Windows, and Microsoft's annual WinHEC conferences provided a setting in which Microsoft could lobby for—and in some cases dictate—the pace and direction of the hardware of the PC industry. Microsoft and Intel had become so important to the ongoing development of PC hardware that industry writers began using the word Wintel to refer to the combined hardware-software system.

This terminology itself is becoming a misnomer, as Intel has lost absolute control over the direction of x86 hardware development with AMD's AMD64. Additionally, non-Windows operating systems like macOS and Linux have established a presence on the x86 architecture.

Design limitations and more compatibility issues

Although the IBM PC was designed for expandability, the designers could not anticipate the hardware developments of the 1980s, nor the size of the industry they would engender. To make things worse, IBM's choice of the Intel 8088 for the CPU introduced several limitations for developing software for the PC compatible platform. For example, the 8088 processor only had a 20-bit memory addressing space. To expand PCs beyond one megabyte, Lotus, Intel, and Microsoft jointly created expanded memory (EMS), a bank-switching scheme to allow more memory provided by add-in hardware, and accessed by a set of four 16-kilobyte "windows" inside the 20-bit addressing. Later, Intel CPUs had larger address spaces and could directly address 16 MB (80286) or more, causing Microsoft to develop extended memory (XMS) which did not require additional hardware.

"Expanded" and "extended" memory have incompatible interfaces, so anyone writing software that used more than one megabyte had to provide for both systems for the greatest compatibility until MS-DOS began including EMM386, which simulated EMS memory using XMS memory. A protected mode OS can also be written for the 80286, but DOS application compatibility was more difficult than expected, not only because most DOS applications accessed the hardware directly, bypassing BIOS routines intended to ensure compatibility, but also that most BIOS requests were made by the first 32 interrupt vectors, which were marked as "reserved" for protected mode processor exceptions by Intel.

Video cards suffered from their own incompatibilities. There was no standard interface for using higher-resolution SVGA graphics modes supported by later video cards. Each manufacturer developed their own methods of accessing the screen memory, including different mode numberings and different bank switching arrangements. The latter were used to address large images within a single 64 KB segment of memory. Previously, the VGA standard had used planar video memory arrangements to the same effect, but this did not easily extend to the greater color depths and higher resolutions offered by SVGA adapters. An attempt at creating a standard named VESA BIOS Extensions (VBE) was made, but not all manufacturers used it.

When the 386 was introduced, again a protected mode OS could be written for it. This time, DOS compatibility was much easier because of virtual 8086 mode. Unfortunately programs could not switch directly between them, so eventually, some new memory-model APIs were developed, VCPI and DPMI, the latter becoming the most popular.

Because of the great number of third-party adapters and no standard for them, programming the PC could be difficult. Professional developers would operate a large test-suite of various known-to-be-popular hardware combinations.

To give consumers some idea of what sort of PC they would need to operate their software, the Multimedia PC (MPC) standard was set during 1990. A PC that met the minimum MPC standard could be marketed with the MPC logo, giving consumers an easy-to-understand specification to look for. Software that could operate on the most minimally MPC-compliant PC would be guaranteed to operate on any MPC. The MPC level 2 and MPC level 3 standards were set later, but the term "MPC compliant" never became popular. After MPC level 3 during 1996, no further MPC standards were established.

Challenges to Wintel domination

| Operating system (vendor) | 1990 | 1992 |

|---|---|---|

| MS-DOS (Microsoft) | 11,648

(of which 490 with Windows) |

18,525

(of which 11,056 with Windows) |

| PC DOS (IBM) | 3,031 | 2,315 |

| DR DOS (Digital Research/Novell) | 1,737 | 1,617 |

| Macintosh System (Apple) | 1,411 | 2,570 |

| Unix (various) | 357 | 797 |

| OS/2 (IBM/Microsoft) | 0 | 409 |

| Others (NEC, Commodore etc.) | 5,079 | 4,458 |

By the late 1990s, the success of Microsoft Windows had driven rival commercial operating systems into near-extinction, and had ensured that the "IBM PC compatible" computer was the dominant computing platform. This meant that if a developer made their software only for the Wintel platform, they would still be able to reach the vast majority of computer users. The only major competitor to Windows with more than a few percentage points of market share was Apple Inc.'s Macintosh. The Mac started out billed as "the computer for the rest of us", but high prices and closed architecture drove the Macintosh into an education and desktop publishing niche, from which it only emerged in the mid-2000s. By the mid-1990s the Mac's market share had dwindled to around 5% and introducing a new rival operating system had become too risky a commercial venture. Experience had shown that even if an operating system was technically superior to Windows, it would be a failure in the market (BeOS and OS/2 for example). In 1989, Steve Jobs said of his new NeXT system, "It will either be the last new hardware platform to succeed, or the first to fail." Four years later in 1993, NeXT announced it was ending production of the NeXTcube and porting NeXTSTEP to Intel processors.

Very early on in PC history, some companies introduced their own XT-compatible chipsets. For example, Chips and Technologies introduced their 82C100 XT Controller which integrated and replaced six of the original XT circuits: one 8237 DMA controller, one 8253 interrupt timer, one 8255 parallel interface controller, one 8259 interrupt controller, one 8284 clock generator, and one 8288 bus controller. Similar non-Intel chipsets appeared for the AT-compatibles, for example OPTi's 82C206 or 82C495XLC which were found in many 486 and early Pentium systems. The x86 chipset market was very volatile though. In 1993, VLSI Technology had become the dominant market player only to be virtually wiped out by Intel a year later. Intel has been the uncontested leader ever since. As the "Wintel" platform gained dominance Intel gradually abandoned the practice of licensing its technologies to other chipset makers; in 2010 Intel was involved in litigation related to their refusal to license their processor bus and related technologies to other companies like Nvidia.

Companies such as AMD and Cyrix developed alternative x86 CPUs that were functionally compatible with Intel's. Towards the end of the 1990s, AMD was taking an increasing share of the CPU market for PCs. AMD even ended up playing a significant role in directing the development of the x86 platform when its Athlon line of processors continued to develop the classic x86 architecture as Intel deviated with its NetBurst architecture for the Pentium 4 CPUs and the IA-64 architecture for the Itanium set of server CPUs. AMD developed AMD64, the first major extension not created by Intel, which Intel later adopted as x86-64. During 2006 Intel began abandoning NetBurst with the release of their set of "Core" processors that represented a development of the earlier Pentium III.

A major alternative to Wintel domination is the rise of alternative operating systems since the early 2000s, which marked as the start of the post-PC era. This would include both the rapid growth of the smartphones (using Android or iOS) as an alternative to the personal computer; and the increasing prevalence of Linux and Unix-like operating systems in the server farms of large corporations such as Google or Amazon.

The IBM PC compatible today

The term "IBM PC compatible" is not commonly used presently because many current mainstream desktop and laptop computers are based on the PC architecture, and IBM no longer makes PCs. The competing hardware architectures have either been discontinued or, like the Amiga, have been relegated to niche, enthusiast markets. The most successful exception is Apple's Macintosh platform, which has used non-Intel processors for the majority of its existence. Macintosh was initially based on the Motorola 68000 series, then transitioned to the PowerPC architecture in 1994 before transitioning to Intel processors beginning in 2006. Until the transition to the internally developed ARM-based Apple silicon in 2020, Macs shared the same system architecture as their Wintel counterparts and could boot Microsoft Windows without a DOS Compatibility Card.

The processor speed and memory capacity of modern PCs are many orders of magnitude greater than they were for the original IBM PC and yet backwards compatibility has been largely maintained – a 32-bit operating system released during the 2000s can still operate many of the simpler programs written for the OS of the early 1980s without needing an emulator, though an emulator like DOSBox now has near-native functionality at full speed (and is necessary for certain games which may run too fast on modern processors). Additionally, many modern PCs can still run DOS directly, although special options such as USB legacy mode and SATA-to-PATA emulation may need to be set in the BIOS setup utility. Computers using the UEFI might need to be set at legacy BIOS mode to be able to boot DOS. However, the BIOS/UEFI options in most mass-produced consumer-grade computers are very limited and cannot be configured to truly handle OSes such as the original variants of DOS.

The spread of the x86-64 architecture has further distanced current computers' and operating systems' internal similarity with the original IBM PC by introducing yet another processor mode with an instruction set modified for 64-bit addressing, but x86-64 capable processors also retain standard x86 compatibility.