Dharma (/ˈdɑːrmə/; Sanskrit: धर्म, pronounced [dʱɐrmɐ] ⓘ) is a key concept in various Indian religions. The term dharma does not have a single, clear translation and conveys a multifaceted idea. Etymologically, it comes from the Sanskrit dhr-, meaning to hold or to support, thus referring to law that sustains things—from one's life to society, and to the Universe at large. In its most commonly used sense, dharma refers to an individual's moral responsibilities or duties; the dharma of a farmer differs from the dharma of a soldier, thus making the concept of dharma a varying dynamic. As with the other components of the Puruṣārtha, the concept of dharma is pan-Indian. The antonym of dharma is adharma.

In Hinduism, dharma denotes behaviour that is considered to be in accord with Ṛta—the "order and custom" that makes life and universe possible. This includes duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and "right way of living" according to the stage of life or social position. Dharma is believed to have a transtemporal validity, and is one of the Puruṣārtha. The concept of dharma was in use in the historical Vedic religion (1500–500 BCE), and its meaning and conceptual scope has evolved over several millennia.

In Buddhism, dharma (Pali: dhamma) refers to the teachings of the Buddha and to the true nature of reality (which the teachings point to). In Buddhist philosophy, dhamma/dharma is also the term for specific "phenomena" and for the ultimate truth. Dharma in Jainism refers to the teachings of Tirthankara (Jina) and the body of doctrine pertaining to purification and moral transformation. In Sikhism, dharma indicates the path of righteousness, proper religious practices, and performing moral duties.

Etymology

The word dharma (/ˈdɑːrmə/) has roots in the Sanskrit dhr-, which means to hold or to support, and is related to Latin firmus (firm, stable). From this, it takes the meaning of "what is established or firm", and hence "law". It is derived from an older Vedic Sanskrit n-stem dharman-, with a literal meaning of "bearer, supporter", in a religious sense conceived as an aspect of Rta.

In the Rigveda, the word appears as an n-stem, dhárman-, with a range of meanings encompassing "something established or firm" (in the literal sense of prods or poles). Figuratively, it means "sustainer" and "supporter" (of deities). It is semantically similar to the Greek themis ("fixed decree, statute, law").

In Classical Sanskrit, and in the Vedic Sanskrit of the Atharvaveda, the stem is thematic: dhárma- (Devanagari: धर्म). In Prakrit and Pali, it is rendered dhamma. In some contemporary Indian languages and dialects it alternatively occurs as dharm.

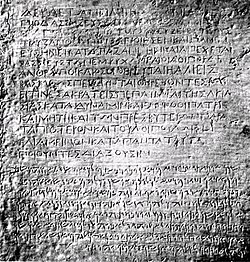

In the 3rd century BCE the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka translated dharma into Greek and Aramaic and he used the Greek word eusebeia (εὐσέβεια, piety, spiritual maturity, or godliness) in the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription and the Kandahar Greek Edicts. In the former, he used the Aramaic word קשיטא (qšyṭ’; truth, rectitude).

Definition

Dharma is a concept of central importance in Indian philosophy and Indian religions. It has multiple meanings in Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism. It is difficult to provide a single concise definition for dharma, as the word has a long and varied history and straddles a complex set of meanings and interpretations. There is no equivalent single-word synonym for dharma in western languages.

There have been numerous, conflicting attempts to translate ancient Sanskrit literature with the word dharma into German, English and French. The concept, claims Paul Horsch, has caused exceptional difficulties for modern commentators and translators. For example, while Grassmann's translation of Rig-Veda identifies seven different meanings of dharma, Karl Friedrich Geldner in his translation of the Rig-Veda employs 20 different translations for dharma, including meanings such as "law", "justice", "righteousness", "order", "duty", "custom", "quality", and "model", among others. However, the word dharma has become a widely accepted loanword in English, and is included in all modern unabridged English dictionaries.

The root of the word dharma is "dhr̥", which means "to support, hold, or bear". It is the thing that regulates the course of change by not participating in change, but that principle which remains constant. Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary, the widely cited resource for definitions and explanation of Sanskrit words and concepts of Hinduism, offers numerous definitions of the word dharma, such as that which is established or firm, steadfast decree, statute, law, practice, custom, duty, right, justice, virtue, morality, ethics, religion, religious merit, good works, nature, character, quality, property. Yet, each of these definitions is incomplete, while the combination of these translations does not convey the total sense of the word. In common parlance, dharma means "right way of living" and "path of rightness". Dharma also has connotations of order, and when combined with the word sanātana, it can also be described as eternal truth.

The meaning of the word dharma depends on the context, and its meaning has evolved as ideas of Hinduism have developed through history. In the earliest texts and ancient myths of Hinduism, dharma meant cosmic law, the rules that created the universe from chaos, as well as rituals; in later Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas and the Epics, the meaning became refined, richer, and more complex, and the word was applied to diverse contexts. In certain contexts, dharma designates human behaviours considered necessary for order of things in the universe, principles that prevent chaos, behaviours and action necessary to all life in nature, society, family as well as at the individual level. Dharma encompasses ideas such as duty, rights, character, vocation, religion, customs and all behaviour considered appropriate, correct or morally upright. For further context, the word varnasramdharma is often used in its place, defined as dharma specifically related to the stage of life one is in. The concept of Dharma is believed to have a transtemporal validity.

The antonym of dharma is adharma (Sanskrit: अधर्म), meaning that which is "not dharma". As with dharma, the word adharma includes and implies many ideas; in common parlance, adharma means that which is against nature, immoral, unethical, wrong or unlawful.

In Buddhism, dharma incorporates the teachings and doctrines of the founder of Buddhism, the Buddha.

History

According to Pandurang Vaman Kane, author of the book History of Dharmaśāstra, the word dharma appears at least fifty-six times in the hymns of the Rigveda, as an adjective or noun. According to Paul Horsch, the word dharma has its origin in Vedic Hinduism. The hymns of the Rigveda claim Brahman created the universe from chaos, they hold (dhar-) the earth and sun and stars apart, they support (dhar-) the sky away and distinct from earth, and they stabilise (dhar-) the quaking mountains and plains.

The Deities, mainly Indra, then deliver and hold order from disorder, harmony from chaos, stability from instability – actions recited in the Veda with the root of word dharma. In hymns composed after the mythological verses, the word dharma takes expanded meaning as a cosmic principle and appears in verses independent of deities. It evolves into a concept, claims Paul Horsch, that has a dynamic functional sense in Atharvaveda for example, where it becomes the cosmic law that links cause and effect through a subject. Dharma, in these ancient texts, also takes a ritual meaning. The ritual is connected to the cosmic, and "dharmani" is equated to ceremonial devotion to the principles that deities used to create order from disorder, the world from chaos.

Past the ritual and cosmic sense of dharma that link the current world to mythical universe, the concept extends to an ethical-social sense that links human beings to each other and to other life forms. It is here that dharma as a concept of law emerges in Hinduism.

Dharma and related words are found in the oldest Vedic literature of Hinduism, in later Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas, and the Epics; the word dharma also plays a central role in the literature of other Indian religions founded later, such as Buddhism and Jainism. According to Brereton, Dharman occurs 63 times in Rig-veda; in addition, words related to Dharman also appear in Rig-veda, for example once as dharmakrt, 6 times as satyadharman, and once as dharmavant, 4 times as dharman and twice as dhariman.

Indo-European parallels for "dharma" are known, but the only Iranian equivalent is Old Persian darmān, meaning "remedy". This meaning is different from the Indo-Aryan dhárman, suggesting that the word "dharma" did not play a major role in the Indo-Iranian period. Instead, it was primarily developed more recently under the Vedic tradition.

It is thought that the Daena of Zoroastrianism, also meaning the "eternal Law" or "religion", is related to Sanskrit "dharma". Ideas in parts overlapping to Dharma are found in other ancient cultures: such as Chinese Tao, Egyptian Maat, Sumerian Me.

Eusebeia and dharma

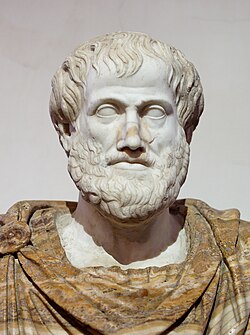

In the mid-20th century, an inscription of the Indian Emperor Asoka from the year 258 BCE was discovered in Afghanistan, the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription. This rock inscription contains Greek and Aramaic text. According to Paul Hacker, on the rock appears a Greek rendering for the Sanskrit word dharma: the word eusebeia.

Scholars of Hellenistic Greece explain eusebeia as a complex concept. Eusebia means not only to venerate deities, but also spiritual maturity, a reverential attitude toward life, and includes the right conduct toward one's parents, siblings and children, the right conduct between husband and wife, and the conduct between biologically unrelated people. This rock inscription, concludes Paul Hacker, suggests dharma in India, about 2300 years ago, was a central concept and meant not only religious ideas, but ideas of right, of good, of one's duty toward the human community.

Rta, maya and dharma

The evolving literature of Hinduism linked dharma to two other important concepts: Ṛta and Māyā. Ṛta in Vedas is the truth and cosmic principle which regulates and coordinates the operation of the universe and everything within it. Māyā in Rig-veda and later literature means illusion, fraud, deception, magic that misleads and creates disorder, thus is contrary to reality, laws and rules that establish order, predictability and harmony. Paul Horsch suggests Ṛta and dharma are parallel concepts, the former being a cosmic principle, the latter being of moral social sphere; while Māyā and dharma are also correlative concepts, the former being that which corrupts law and moral life, the later being that which strengthens law and moral life.

Day proposes dharma is a manifestation of Ṛta, but suggests Ṛta may have been subsumed into a more complex concept of dharma, as the idea developed in ancient India over time in a nonlinear manner. The following verse from the Rigveda is an example where rta and dharma are linked:

O Indra, lead us on the path of Rta, on the right path over all evils...

— RV 10.133.6

Hinduism

Dharma is an organising principle in Hinduism that applies to human beings in solitude, in their interaction with human beings and nature, as well as between inanimate objects, to all of cosmos and its parts. It refers to the order and customs which make life and universe possible, and includes behaviours, rituals, rules that govern society, and ethics. Hindu dharma includes the religious duties, moral rights and duties of each individual, as well as behaviours that enable social order, right conduct, and those that are virtuous. Dharma, according to Van Buitenen, is that which all existing beings must accept and respect to sustain harmony and order in the world. It is neither the act nor the result, but the natural laws that guide the act and create the result to prevent chaos in the world. It is innate characteristic, that makes the being what it is. It is, claims Van Buitenen, the pursuit and execution of one's nature and true calling, thus playing one's role in cosmic concert. In Hinduism, it is the dharma of the bee to make honey, of cow to give milk, of sun to radiate sunshine, of river to flow. In terms of humanity, dharma is the need for, the effect of and essence of service and interconnectedness of all life. This includes duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and "right way of living".

In its true essence, dharma means for a Hindu to "expand the mind". Furthermore, it represents the direct connection between the individual and the societal phenomena that bind the society together. In the way societal phenomena affect the conscience of the individual, similarly may the actions of an individual alter the course of the society, for better or for worse. This has been subtly echoed by the credo धर्मो धारयति प्रजा: meaning dharma is that which holds and provides support to the social construct.

In Hinduism, dharma generally includes various aspects:

- Sanātana Dharma, the eternal and unchanging principals of dharma.

- Varṇ āśramā dharma, one's duty at specific stages of life or inherent duties.

- Svadharma, one's own individual or personal duty.

- Āpad dharma, dharma prescribed at the time of adversities.

- Sadharana dharma, moral duties irrespective of the stages of life.

- Yuga dharma, dharma which is valid for a yuga, an epoch or age as established by Hindu tradition and thus may change at the conclusion of its time.

In Vedas and Upanishads

The history section of this article discusses the development of dharma concept in Vedas. This development continued in the Upanishads and later ancient scripts of Hinduism. In Upanishads, the concept of dharma continues as universal principle of law, order, harmony, and truth. It acts as the regulatory moral principle of the Universe. It is explained as law of righteousness and equated to satya (Sanskrit: सत्यं, truth), in hymn 1.4.14 of Brhadaranyaka Upanishad, as follows:

Nothing is higher than dharma. The weak overcomes the stronger by dharma, as over a king. Truly that dharma is the Truth (Satya); Therefore, when a man speaks the Truth, they say, "He speaks the Dharma"; and if he speaks Dharma, they say, "He speaks the Truth!" For both are one.

— Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 1.4.xiv

Dharma and Mimamsa

Mimamsa, developed through commentaries on its foundational texts, particularly the Mimamsa Sutras attributed to Jaimini, emphasizes "the desire to know dharma" as the central concern, defining dharma as what connects a person with the highest good, always yet to be realized. While some schools associate dharma with post-mortem existence, Mimamsakas focus on the continual renewal and realization of a ritual world through adherence to Vedic injunctions. They assert that the ultimate good is essentially inaccessible to perception and can only be understood through language, reflecting confidence in Vedic injunctions and the reality of language as a means of knowing.

Mimamsa addresses the delayed results of actions (like wealth or heaven) through the concept of apurva or adrsta, an unseen force that preserves the connection between actions and their outcomes. This ensures that Vedic sacrifices, though their results are delayed, are effective and reliable in guiding toward dharma.

In the Epics

The Hindu religion and philosophy, claims Daniel Ingalls, places major emphasis on individual practical morality. In the Sanskrit epics, this concern is omnipresent. In Hindu Epics, the good, morally upright, law-abiding king is referred to as "dharmaraja".

Dharma is at the centre of all major events in the life of Dasharatha, Rama, Sita, and Lakshman in Ramayana. In the Ramayana, Dasharatha upholds his dharma by honoring a promise to Kaikeyi, resulting in his beloved son Rama's exile, even though it brings him immense personal suffering.

In the Mahabharata, dharma is central, and it is presented through symbolism and metaphors. Near the end of the epic, Yama referred to as dharma in the text, is portrayed as taking the form of a dog to test the compassion of Yudhishthira, who is told he may not enter paradise with such an animal. Yudhishthira refuses to abandon his companion, for which he is then praised by dharma. The value and appeal of the Mahabharata, according to Ingalls, is not as much in its complex and rushed presentation of metaphysics in the 12th book. Indian metaphysics, he argues, is more eloquently presented in other Sanskrit scriptures. Instead, the appeal of Mahabharata, like Ramayana, lies in its presentation of a series of moral problems and life situations, where there are usually three answers: one answer is of Bhima, which represents brute force, an individual angle representing materialism, egoism, and self; the second answer is of Yudhishthira, which appeals to piety, deities, social virtue, and tradition; the third answer is of introspective Arjuna, which falls between the two extremes, and who, claims Ingalls, symbolically reveals the finest moral qualities of man. The Epics of Hinduism are a symbolic treatise about life, virtues, customs, morals, ethics, law, and other aspects of dharma. There is extensive discussion of dharma at the individual level in the Epics of Hinduism; for example, on free will versus destiny, when and why human beings believe in either, the strong and prosperous naturally uphold free will, while those facing grief or frustration naturally lean towards destiny. The Epics of Hinduism illustrate various aspects of dharma with metaphors.

According to 4th-century Vatsyayana

According to Klaus Klostermaier, 4th-century CE Hindu scholar Vātsyāyana explained dharma by contrasting it with adharma. Vātsyāyana suggested that dharma is not merely in one's actions, but also in words one speaks or writes, and in thought. According to Vātsyāyana:

- Adharma of body: hinsa (violence), steya (steal, theft), pratisiddha maithuna (sexual indulgence with someone other than one's partner)

- Dharma of body: dana (charity), paritrana (succor of the distressed) and paricarana (rendering service to others)

- Adharma from words one speaks or writes: mithya (falsehood), parusa (caustic talk), sucana (calumny) and asambaddha (absurd talk)

- Dharma from words one speaks or writes: satya (truth and facts), hitavacana (talking with good intention), priyavacana (gentle, kind talk), svadhyaya (self-study)

- Adharma of mind: paradroha (ill will to anyone), paradravyabhipsa (covetousness), nastikya (denial of the existence of morals and religiosity)

- Dharma of mind: daya (compassion), asprha (disinterestedness), and sraddha (faith in others)

According to Patanjali Yoga

In the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali the dharma is real; in the Vedanta it is unreal.

Dharma is part of yoga, suggests Patanjali; the elements of Hindu dharma are the attributes, qualities and aspects of yoga. Patanjali explained dharma in two categories: yamas (restraints) and niyamas (observances).

The five yamas, according to Patanjali, are: abstain from injury to all living creatures, abstain from falsehood (satya), abstain from unauthorised appropriation of things-of-value from another (acastrapurvaka), abstain from coveting or sexually cheating on your partner, and abstain from expecting or accepting gifts from others. The five yama apply in action, speech and mind. In explaining yama, Patanjali clarifies that certain professions and situations may require qualification in conduct. For example, a fisherman must injure a fish, but he must attempt to do this with least trauma to fish and the fisherman must try to injure no other creature as he fishes.

The five niyamas (observances) are cleanliness by eating pure food and removing impure thoughts (such as arrogance or jealousy or pride), contentment in one's means, meditation and silent reflection regardless of circumstances one faces, study and pursuit of historic knowledge, and devotion of all actions to the Supreme Teacher to achieve perfection of concentration.

Sources

Dharma is an empirical and experiential inquiry for every man and woman, according to some texts of Hinduism. For example, Apastamba Dharmasutra states:

Dharma and Adharma do not go around saying, "That is us." Neither do gods, nor gandharvas, nor ancestors declare what is Dharma and what is Adharma.

— Apastamba Dharmasutra

In other texts, three sources and means to discover dharma in Hinduism are described. These, according to Paul Hacker, are: First, learning historical knowledge such as Vedas, Upanishads, the Epics and other Sanskrit literature with the help of one's teacher. Second, observing the behaviour and example of good people. The third source applies when neither one's education nor example exemplary conduct is known. In this case, "atmatusti" is the source of dharma in Hinduism, that is the good person reflects and follows what satisfies his heart, his own inner feeling, what he feels driven to.

Dharma, life stages and social stratification

Some texts of Hinduism outline dharma for society and at the individual level. Of these, the most cited one is Manusmriti, which describes the four Varnas, their rights and duties. Most texts of Hinduism, however, discuss dharma with no mention of Varna (caste). Other dharma texts and Smritis differ from Manusmriti on the nature and structure of Varnas. Yet, other texts question the very existence of varna. Bhrigu, in the Epics, for example, presents the theory that dharma does not require any varnas. In practice, medieval India is widely believed to be a socially stratified society, with each social strata inheriting a profession and being endogamous. Varna was not absolute in Hindu dharma; individuals had the right to renounce and leave their Varna, as well as their asramas of life, in search of moksa. While neither Manusmriti nor succeeding Smritis of Hinduism ever use the word varnadharma (that is, the dharma of varnas), or varnasramadharma (that is, the dharma of varnas and asramas), the scholarly commentary on Manusmriti use these words, and thus associate dharma with varna system of India. In 6th-century India, even Buddhist kings called themselves "protectors of varnasramadharma" – that is, dharma of varna and asramas of life.

At the individual level, some texts of Hinduism outline four āśramas, or stages of life as individual's dharma. These are: (1) brahmacārya, the life of preparation as a student, (2) gṛhastha, the life of the householder with family and other social roles, (3) vānprastha or aranyaka, the life of the forest-dweller, transitioning from worldly occupations to reflection and renunciation, and (4) sannyāsa, the life of giving away all property, becoming a recluse and devotion to moksa, spiritual matters. Patrick Olivelle suggests that "ashramas represented life choices rather than sequential steps in the life of a single individual" and the vanaprastha stage was added before renunciation over time, thus forming life stages.

The four stages of life complete the four human strivings in life, according to Hinduism. Dharma enables the individual to satisfy the striving for stability and order, a life that is lawful and harmonious, the striving to do the right thing, be good, be virtuous, earn religious merit, be helpful to others, interact successfully with society. The other three strivings are Artha – the striving for means of life such as food, shelter, power, security, material wealth, and so forth; Kama – the striving for sex, desire, pleasure, love, emotional fulfilment, and so forth; and Moksa – the striving for spiritual meaning, liberation from life-rebirth cycle, self-realisation in this life, and so forth. The four stages are neither independent nor exclusionary in Hindu dharma.

Dharma and poverty

Dharma being necessary for individual and society, is dependent on poverty and prosperity in a society, according to Hindu dharma scriptures. For example, according to Adam Bowles, Shatapatha Brahmana 11.1.6.24 links social prosperity and dharma through water. Waters come from rains, it claims; when rains are abundant there is prosperity on the earth, and this prosperity enables people to follow Dharma – moral and lawful life. In times of distress, of drought, of poverty, everything suffers including relations between human beings and the human ability to live according to dharma.

In Rajadharmaparvan 91.34-8, the relationship between poverty and dharma reaches a full circle. A land with less moral and lawful life suffers distress, and as distress rises it causes more immoral and unlawful life, which further increases distress. Those in power must follow the raja dharma (that is, dharma of rulers), because this enables the society and the individual to follow dharma and achieve prosperity.

Dharma and law

The notion of dharma as duty or propriety is found in India's ancient legal and religious texts. Common examples of such use are pitri dharma (meaning a person's duty as a father), putra dharma (a person's duty as a son), raj dharma (a person's duty as a king) and so forth. In Hindu philosophy, justice, social harmony, and happiness requires that people live per dharma. The Dharmashastra is a record of these guidelines and rules. The available evidence suggest India once had a large collection of dharma related literature (sutras, shastras); four of the sutras survive and these are now referred to as Dharmasutras. Along with laws of Manu in Dharmasutras, exist parallel and different compendium of laws, such as the laws of Narada and other ancient scholars. These different and conflicting law books are neither exclusive, nor do they supersede other sources of dharma in Hinduism. These Dharmasutras include instructions on education of the young, their rites of passage, customs, religious rites and rituals, marital rights and obligations, death and ancestral rites, laws and administration of justice, crimes, punishments, rules and types of evidence, duties of a king, as well as morality.

Buddhism

Buddhism held the Hindu view of Dharma as "cosmic law", as in the working of Karma. The term Dharma (Pali: dhamma) later came to refer to the teachings of the Buddha (pariyatti); the practice (paṭipatti) of the Buddha's teachings is then comprehended as Dharma. In Buddhist philosophy, dhamma/dharma is also the term for "phenomena".

Buddha's teachings

For practising Buddhists, references to dharma (dhamma in Pali) particularly as "the dharma", generally means the teachings of the Buddha, commonly known throughout the East as Buddhadharma. It includes especially the discourses on the fundamental principles (such as the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path), as opposed to the parables and to the poems. The Buddha's teachings explain that in order to end suffering, dharma, or the right thoughts, understanding, actions and livelihood, should be cultivated.

The status of dharma is regarded variably by different Buddhist traditions. Some regard it as an ultimate truth, or as the fount of all things which lie beyond the "three realms" (Sanskrit: tridhatu) and the "wheel of becoming" (Sanskrit: bhavachakra). Others, who regard the Buddha as simply an enlightened human being, see the dharma as the essence of the "84,000 different aspects of the teaching" (Tibetan: chos-sgo brgyad-khri bzhi strong) that the Buddha gave to various types of people, based upon their individual propensities and capabilities.

Dharma refers not only to the sayings of the Buddha, but also to the later traditions of interpretation and addition that the various schools of Buddhism have developed to help explain and to expound upon the Buddha's teachings. For others still, they see the dharma as referring to the "truth", or the ultimate reality of "the way that things really are" (Tibetan: Chö).

The dharma is one of the Three Jewels of Buddhism in which practitioners of Buddhism seek refuge, or that upon which one relies for his or her lasting happiness. The Three Jewels of Buddhism are the Buddha, meaning the mind's perfection of enlightenment, the dharma, meaning the teachings and the methods of the Buddha, and the Sangha, meaning the community of practitioners who provide one another guidance and support.

Chan Buddhism

Dharma is employed in Chan Buddhism in a specific context in relation to transmission of authentic doctrine, understanding and bodhi; recognised in dharma transmission.

Theravada Buddhism

In Theravada Buddhism obtaining ultimate realisation of the dhamma is achieved in three phases; learning, practising and realising.

In Pali:

- Pariyatti – the learning of the theory of dharma as contained within the suttas of the Pali canon

- Patipatti – putting the theory into practice and

- Pativedha – when one penetrates the dharma or through experience realises the truth of it.

Jainism

The word dharma in Jainism is found in all its key texts. It has a contextual meaning and refers to a number of ideas. In the broadest sense, it means the teachings of the Jinas, or teachings of any competing spiritual school, a supreme path, socio-religious duty, and that which is the highest mangala (holy).

The Tattvartha Sutra, a major Jain text, mentions daśa dharma (lit. 'ten dharmas') with referring to ten righteous virtues: forbearance, modesty, straightforwardness, purity, truthfulness, self-restraint, austerity, renunciation, non-attachment, and celibacy. Ācārya Amṛtacandra, author of the Jain text, Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya writes:

A right believer should constantly meditate on virtues of dharma, like supreme modesty, in order to protect the Self from all contrary dispositions. He should also cover up the shortcomings of others.

— Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya (27)

Dharmāstikāya

The term dharmāstikāya (Sanskrit: धर्मास्तिकाय) also has a specific ontological and soteriological meaning in Jainism, as a part of its theory of six dravya (substance or a reality). In the Jain tradition, existence consists of jīva (soul, ātman) and ajīva (non-soul, anātman), the latter consisting of five categories: inert non-sentient atomic matter (pudgalāstikāya), space (ākāśa), time (kāla), principle of motion (dharmāstikāya), and principle of rest (adharmāstikāya). The use of the term dharmāstikāya to mean motion and to refer to an ontological sub-category is peculiar to Jainism, and not found in the metaphysics of Buddhism and various schools of Hinduism.

Sikhism

For Sikhs, the word dharam (Punjabi: ਧਰਮ, romanized: dharam) means the path of righteousness and proper religious practice. Guru Granth Sahib connotes dharma as duty and moral values. The 3HO movement in Western culture, which has incorporated certain Sikh beliefs, defines Sikh Dharma broadly as all that constitutes religion, moral duty and way of life.

In Sangam literature

Several works of the Sangam and post-Sangam period, many of which are of Hindu or Jain origin, emphasizes on dharma. Most of these texts are based on aṟam, the Tamil term for dharma. The ancient Tamil moral text of the Tirukkuṟaḷ or Kural, a text probably of Jain or Hindu origin, despite being a collection of aphoristic teachings on dharma (aram), artha (porul), and kama (inpam), is completely and exclusively based on aṟam. The Naladiyar, a Jain text of the post-Sangam period, follows a similar pattern as that of the Kural in emphasizing aṟam or dharma.

Dharma in symbols

The importance of dharma to Indian civilization is illustrated by India's decision in 1947 to include the Ashoka Chakra, a depiction of the dharmachakra (the "wheel of dharma"), as the central motif on its flag.