| Cannabis |

Flowering cannabis plant

|

| Botanical |

Cannabis |

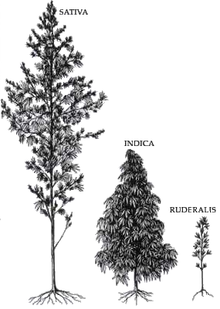

| Source plant(s) |

Cannabis sativa, Cannabis sativa forma indica, Cannabis ruderalis |

| Part(s) of plant |

flower |

| Geographic origin |

Central and South Asia.[1] |

| Active ingredients |

Tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol, cannabinol, tetrahydrocannabivarin |

| Main producers |

Afghanistan,[2] Canada,[3] China,[4][not in citation given] Colombia,[5] India,[2] Jamaica,[2] Mexico,[6] Morocco,[2] Netherlands, Pakistan, Paraguay,[6] Spain,[2] Thailand, Turkey, United States[2] |

|

Cannabis, commonly known as

marijuana[7] and by numerous other names,

a[›] is a

preparation of the

Cannabis plant intended for use as a

psychoactive drug and as

medicine.

[8][9] Pharmacologically, the principal

psychoactive constituent of cannabis is

tetrahydrocannabinol (THC); it is one of 483 known compounds in the plant,

[10] including at least 84 other

cannabinoids, such as

cannabidiol (CBD),

cannabinol (CBN),

tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV),

[11][12] and

cannabigerol (CBG).

Cannabis is often consumed for

its psychoactive and physiological effects, which can include heightened mood or

euphoria, relaxation,

[13] and an increase in appetite.

[14] Possible side-effects include a

decrease in short-term memory,

dry mouth, impaired motor skills, reddening of the eyes,

[13] and feelings of paranoia or anxiety.

[15]

Modern uses of cannabis are as a

recreational or

medicinal drug, and as part of

religious or spiritual rites; the earliest recorded uses date from the 3rd millennium BC.

[16] Since the early 20th century cannabis has been subject to

legal restrictions with the

possession, use, and sale of cannabis preparations containing psychoactive cannabinoids currently

illegal in most countries of the world; the

United Nations deems it the most-used illicit drug in the world.

[17][18] In 2004, the United Nations estimated that global consumption of cannabis indicated that approximately 4% of the

adult world population (162 million people) used cannabis annually, and that approximately 0.6% (22.5 million) of people used cannabis daily.

[19] Medical marijuana refers to the use of the

Cannabis plant as a physician-recommended

herbal therapy, which is taking place in

Canada,

Belgium,

Australia, the

Netherlands,

Spain, and

several U.S. states.

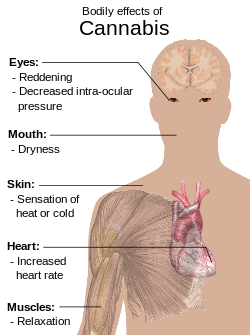

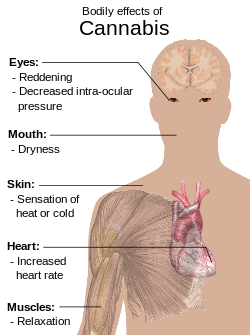

Effects

Main short-term physical effects of cannabis

Cannabis has psychoactive and physiological effects when consumed.

[20] The immediate desired effects from consuming cannabis include relaxation and mild euphoria (the "high" or "stoned" feeling), while some immediate undesired side-effects include a decrease in short-term memory, dry mouth, impaired motor skills and reddening of the eyes.

[21] Aside from a subjective change in perception and mood, the most common short-term physical and neurological effects include increased heart rate, increased appetite and consumption of food, lowered blood pressure, impairment of short-term and working memory,

[22][23] psychomotor coordination, and concentration.

A 2013 literature review said that exposure to marijuana had biologically-based physical, mental, behavioral and social health consequences and was "associated with diseases of the liver (particularly with co-existing

hepatitis C), lungs, heart, and vasculature".

[24]

Cannabis has been used

to reduce nausea and vomiting in

chemotherapy and people with

AIDS, and to treat pain and

muscle spasticity.

[25] According to a 2013 review, "Safety concerns regarding cannabis include the increased risk of developing schizophrenia with adolescent use, impairments in memory and cognition, accidental pediatric ingestions, and lack of safety packaging for medical cannabis formulations."

[25]

The medicinal value of cannabis is disputed. The

American Society of Addiction Medicine dismisses the concept of medical cannabis because of concerns about its potential for dependence and adverse health effects. The US

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) states that the herb cannabis is associated with numerous harmful health effects, and that significant aspects such as content, production, and supply are unregulated. The FDA approves of the prescription of two products (not for smoking) that have pure

THC in a small controlled dose as the active substance.

[26][27]

Neurological

A 2013 review comparing different structural and functional imaging studies showed morphological brain alterations in long-term cannabis users which were found to possibly correlate to cannabis exposure.

[28] A 2010 review found resting blood flow to be lower globally and in prefrontal areas of the brain in cannabis users, when compared to non-users. It was also shown that giving THC or cannabis correlated with increased bloodflow in these areas, and facilitated activation of the

anterior cingulate cortex and

frontal cortex when participants were presented with assignments demanding use of cognitive capacity.

[29] Both reviews noted that some of the studies that they examined had methodological limitations, for example small

sample sizes or not distinguishing adequately between cannabis and alcohol consumption.

[28][29]

Gateway drug

The Gateway Hypothesis states that cannabis use increases the probability of trying "harder" drugs. The hypothesis has been hotly debated as it is regarded by some as the primary rationale for the United States prohibition on cannabis use.

[30][31] A Pew Research Center poll found that political opposition to marijuana use was significantly associated with concerns about health effects and whether legalization would increase marijuana use by children.

[32]

Some studies state that while there is no proof for the gateway hypothesis,

[33] young cannabis users should still be considered as a risk group for intervention programs.

[34] Other findings indicate that

hard drug users are likely to be

poly-drug users, and that interventions must address the use of multiple drugs instead of a single hard drug.

[35] Almost two-thirds of the

poly drug users in the "2009/10 Scottish Crime and Justice Survey" used cannabis.

[36]

The gateway effect may appear due to social factors involved in using any illegal drug. Because of the illegal status of cannabis, its consumers are likely to find themselves in situations allowing them to acquaint with individuals using or selling other illegal drugs.

[37][38] Utilizing this argument some studies have shown that alcohol and tobacco may additionally be regarded as gateway drugs;

[39] however, a more parsimonious explanation could be that cannabis is simply more readily available (and at an earlier age) than illegal hard drugs. In turn alcohol and tobacco are easier to obtain at an earlier point than is cannabis (though the reverse may be true in some areas), thus leading to the "gateway sequence" in those individuals since they are most likely to experiment with any drug offered.

[30]

An alternative to the gateway hypothesis is the

Common Liability to Addiction theory (CLA). It states that some individuals are, for various reasons, willing to try multiple recreational substances. The "gateway" drugs are merely those that are (usually) available at an earlier age than the harder drugs. Researchers have noted in an extensive review,

Vanyukov et al., that it is dangerous to present the sequence of events described in gateway "theory" in causative terms as this hinders both research and intervention.

[40]

Safety

Fatal overdoses associated with cannabis use have not been reported as of 2008.

[41] There has been too little research to determine whether cannabis users die at a higher rate as compared to the general population, though some studies suggest that fatal motor vehicle accidents and death from respiratory and brain cancers may be more frequent among heavy cannabis users. It is not clear whether cannabis use affects the rate of suicide.

[41]

THC, the principal

psychoactive constituent of the cannabis plant, has low

toxicity, the dose of THC needed to kill 50% of tested rodents is very high,

[42] and human deaths from overdose are extremely rare, usually following the injection of hashish oil.

[43]

Evaluations of safety and tolerability of

Sativex, a pharmacological preparation made from a low dose of

cannabinoids, have concluded that it is indeed well-tolerated and, in one class of patients, useful.

[44]

Many studies have looked at the

effects of smoking cannabis on the respiratory system. Cannabis smoke contains thousands of organic and inorganic chemical compounds. This

tar is chemically similar to that found in tobacco smoke,

[45] and over fifty known

carcinogens have been identified in cannabis smoke,

[46] including; nitrosamines, reactive aldehydes, and polycylic hydrocarbons, including benz[a]pyrene.

[47] Combustion products are not present when using a

vaporizer, consuming THC in pill form, or consuming

cannabis foods.

There is serious suspicion among cardiologists, spurring research but falling short of definitive proof, that cannabis use has the potential to contribute to cardiovascular disease. Cannabis is believed to be an aggravating factor in rare cases of

arteritis, a serious condition that in some cases leads to amputation. Because 97% of case-reports also smoked tobacco, a formal association with cannabis could not be made. If cannabis arteritis turns out to be a distinct clinical entity, it might be the consequence of

vasoconstrictor activity observed from

delta-8-THC and

delta-9-THC.

[48] Other serious cardiovascular events including

myocardial infarction,

stroke,

sudden cardiac death, and

cardiomyopathy have been reported to be temporally associated with cannabis use. Research in these events is complicated because cannabis is often used in conjunction with tobacco, and drugs such as alcohol and cocaine.

[49] These putative effects can be taken in context of a wide range of cardiovascular phenomena regulated by the

endocannabinoid system and an overall role of cannabis in causing decreased peripheral resistance and increased

cardiac output, which potentially could pose a threat to those with cardiovascular disease.

[50]

Varieties and strains

CBD is a

5-HT1A receptor agonist, which may also contribute to an

anxiolytic effect.

[51] This likely means the high concentrations of CBD found in

Cannabis indica mitigate the

anxiogenic effect of THC significantly.

[51] The effects of sativa are well known for their cerebral high, hence its daytime use as medical cannabis, while indica is well known for its sedative effects and preferred night time use as medical cannabis.

[51]

Concentration of psychoactive ingredients

According to the

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), "the amount of THC present in a cannabis sample is generally used as a measure of cannabis potency."

[52] The three main forms of cannabis products are the flower, resin (hashish), and oil (hash oil). The UNODC states that cannabis often contains 5% THC content, resin "can contain up to 20% THC content", and that "Cannabis oil may contain more than 60% THC content."

[52]

A scientific study published in 2000 in the

Journal of Forensic Sciences (JFS) found that the potency (THC content) of confiscated cannabis in the United States (US) rose from "approximately 3.3% in 1983 and 1984", to "4.47% in 1997". The study also concluded that "other major cannabinoids (i.e., CBD,

CBN, and

CBC)" (other chemicals in cannabis) "showed no significant change in their concentration over the years".

[53] More recent research undertaken at the University of Mississippi's Potency Monitoring Project found that average THC levels in cannabis samples between 1975 and 2007 steadily increased,

[54] for example THC levels in 1985 averaged 3.48% by 2006 this had increased to an average of 8.77%.

[54]

Australia's

National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre (NCPIC) states that the buds (flowers) of the female cannabis plant contain the highest concentration of THC, followed by the leaves. The stalks and seeds have "much lower THC levels".

[55] The UN states that leaves can contain ten times less THC than the buds, and the stalks one hundred times less THC.

[52]

After revisions to

cannabis rescheduling in the UK, the government moved cannabis back from a

class C to a

class B drug. A purported reason was the appearance of high potency cannabis. They believe

skunk accounts for between 70 and 80% of samples seized by police

[56] (despite the fact that skunk can sometimes be incorrectly mistaken for all types of herbal cannabis).

[57][58] Extracts such as

hashish and

hash oil typically contain more THC than high potency cannabis flowers.

[59]

Preparations

Marijuana

Marijuana consists of the dried flowers and subtending leaves and stems of the female

Cannabis plant.

[60][61] This is the most widely consumed form, containing 3% to 20% THC,

[62] with reports of up-to 33% THC.

[63] In contrast, cannabis varieties used to produce industrial hemp contain less than 1% THC and are thus not valued for recreational use.

[64]

This is the stock material from which all other preparations are derived. It is noted that cannabis or its extracts must be sufficiently heated or dehydrated to cause

decarboxylation of its most abundant cannabinoid, tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA), into psychoactive THC.

[65]

Kief

Kief is a powder, rich in

trichomes,

[66] which can be sifted from the leaves and flowers of cannabis plants and either

consumed in powder form or compressed to produce cakes of

hashish.

[67] The word "kif" derives from

colloquial Arabic كيف kēf/kīf, meaning

pleasure.

[68]

Hashish

Hashish (also spelled hasheesh, hashisha, or simply hash) is a concentrated

resin cake or ball produced from pressed kief, the detached trichomes and fine material that falls off of cannabis flowers and leaves.

[69] It varies in color from black to golden brown depending upon purity and variety of cultivar it was obtained from.

[70] It can be consumed orally or smoked.

[71]

Tincture

Cannabinoids can be

extracted from cannabis plant matter using high-

proof spirits (often

grain alcohol) to create a

tincture, often referred to as "green dragon".

[72] Nabiximols is a branded product name from a tincture manufacturing pharmaceutical company.

[73]

Hash oil

Hash oil is obtained from the cannabis plant by solvent extraction, and contains the cannabinoids present in the natural oils of cannabis flowers and leaves.

[74] The solvents are evaporated to leave behind a very concentrated oil. Owing to its purity, hash oil is consumed by smoking, vaporizing, eating, or topical application. Hash oil is very different from both

hemp seed oil and

cannabis flower essential oil.

[75]

Infusions

There are many varieties of cannabis infusions owing to the variety of non-volatile solvents used. The plant material is mixed with the solvent and then pressed and filtered to express the oils of the plant into the solvent. Examples of solvents used in this process are cocoa butter, dairy butter, cooking oil,

glycerine, and skin moisturizers. Depending on the solvent, these may be used in

cannabis foods or applied topically.

[76]

Adulterated cannabis

Contaminants may be found in

hashish obtained from "soap bar"-type sources.

[77] The dried flowers of the plant may be contaminated by the plant taking up heavy metals and other toxins from its growing environment,

[78] or by the addition of glass.

[79] In the Netherlands, chalk has been used to make cannabis appear to be of a higher quality.

[80] Increasing the weight of hashish products in Germany with lead caused

lead intoxication in at least 29 users.

[81]

Despite cannabis being generally perceived as a natural product,

[82] in a recent Australian survey

[83] one in four Australians consider cannabis grown indoors under hydroponic conditions to be a greater health risk due to increased contamination, added to the plant during cultivation to enhance the plant growth and quality.

Consumption

A joint prior to rolling, with a paper handmade filter on the left

A forced-air vaporizer. The detachable balloon (top) fills with vapors that are then inhaled

Methods of consumption

Cannabis is consumed in many different ways:

[84]

- vaporizer, which heats herbal cannabis to 165–190 °C (329–374 °F),[86] causing the active ingredients to evaporate into a vapor without burning the plant material (the boiling point of THC is 157 °C (315 °F) at 760 mmHg pressure).[87]

- cannabis tea, which contains relatively small concentrations of THC because THC is an oil (lipophilic) and is only slightly water-soluble (with a solubility of 2.8 mg per liter).[88] Cannabis tea is made by first adding a saturated fat to hot water (e.g. cream or any milk except skim) with a small amount of cannabis.[89]

- edibles, where cannabis is added as an ingredient to one of a variety of foods.

Marijuana vending machines for selling or dispensing cannabis are in use in the United States and are planned to be used in Canada.

[90]

Mechanism of action

The high lipid-solubility of cannabinoids results in their persisting in the body for long periods of time.

[91] Even after a single administration of THC, detectable levels of THC can be found in the body for weeks or longer (depending on the amount administered and the sensitivity of the assessment method).

[91] A number of investigators have suggested that this is an important factor in marijuana's effects, perhaps because cannabinoids may accumulate in the body, particularly in the lipid membranes of neurons.

[92]

Not until the end of the 20th century was the specific mechanism of action of THC at the neuronal level studied. Researchers have subsequently confirmed that THC exerts its most prominent effects via its actions on two types of

cannabinoid receptors, the

CB1 receptor and the

CB2 receptor, both of which are G-protein coupled receptors.

[93] The CB1 receptor is found primarily in the brain as well as in some peripheral tissues, and the CB2 receptor is found primarily in peripheral tissues, but is also expressed in

neuroglial cells.

[94] THC appears to alter mood and cognition through its agonist actions on the CB1 receptors, which inhibit a secondary messenger system (adenylate cyclase) in a dose dependent manner. These actions can be blocked by the selective CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A (rimonabant), which has been shown in clinical trials to be an effective treatment for smoking cessation, weight loss, and as a means of controlling or reducing metabolic syndrome risk factors.

[95] However, due to the dysphoric effect of CB1 antagonists, this drug is often discontinued due to these side effects.

[96]

Via CB1 activation, THC indirectly increases dopamine release and produces psychotropic effects. Cannabidiol also acts as an allosteric modulator of the mu and delta opioid receptors.

[97] THC also potentiates the effects of the glycine receptors.

[98] The role of these interactions in the "marijuana high" remains elusive.

[citation needed]

Detection of consumption

THC and its major (inactive) metabolite, THC-COOH, can be measured in blood, urine, hair, oral fluid or sweat using

chromatographic techniques as part of a drug use testing program or a forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal offense.

[99] The concentrations obtained from such analyses can often be helpful in distinguishing active use from passive exposure, elapsed time since use, and extent or duration of use. These tests cannot, however, distinguish authorized cannabis smoking for medical purposes from unauthorized recreational smoking.

[100] Commercial cannabinoid

immunoassays, often employed as the initial screening method when testing physiological specimens for marijuana presence, have different degrees of cross-reactivity with THC and its metabolites.

[101] Urine contains predominantly THC-COOH, while hair, oral fluid and sweat contain primarily THC.

[99] Blood may contain both substances, with the relative amounts dependent on the recency and extent of usage.

[99]

The

Duquenois-Levine test is commonly used as a

screening test in the field, but it cannot definitively confirm the presence of cannabis, as a large range of substances have been shown to give false positives. Despite this, it is common in the United States for prosecutors to seek

plea bargains on the basis of positive D-L tests, claiming them definitive, or even to seek conviction without the use of gas chromatography confirmation, which can only be done in the lab.

[102] In 2011, researchers at John Jay College of Criminal Justice reported that dietary zinc supplements can mask the presence of THC and other drugs in urine.

[103]

Production

It is often claimed by growers and breeders of herbal cannabis that advances in breeding and cultivation techniques have increased the potency of cannabis since the late 1960s and early '70s, when THC was first discovered and understood. However, potent seedless cannabis such as "

Thai sticks" were already available at that time.

Sinsemilla (Spanish for "without seed") is the dried, seedless inflorescences of female cannabis plants. Because THC production drops off once pollination occurs, the male plants (which produce little THC themselves) are eliminated before they shed pollen to prevent pollination. Advanced cultivation techniques such as

hydroponics,

cloning,

high-intensity artificial lighting, and

the sea of green method are frequently employed as a response (in part) to prohibition enforcement efforts that make outdoor cultivation more risky. It is often cited that the average levels of THC in cannabis sold in United States rose dramatically between the 1970s and 2000, but such statements are likely skewed because of undue weight given to much more expensive and potent, but less prevalent samples.

[104]

"Skunk" refers to several named strains of potent cannabis, grown through selective breeding and sometimes

hydroponics. It is a cross-breed of

Cannabis sativa and

C. indica (although other strains of this mix exist in abundance). Skunk cannabis potency ranges usually from 6% to 15% and rarely as high as 20%. The average THC level in

coffee shops in the Netherlands is about 18–19%.

[105]

Price

The price or street value of cannabis varies widely depending on geographic area and potency.

[106]

In the United States, cannabis is overall the number four value crop, and is number one or two in many states including California, New York and Florida, averaging $3,000/lb.

[107][108] It is believed to generate an estimated $36 billion market.

[109] The

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime claims in its 2008 World Drug Report that typical U.S. retail prices are $10–15 per gram (approximately $280–420 per

ounce). Street prices in North America are known to range from about $40 to $400 per ounce, depending on quality.

[110] In

Washington and

Colorado, however, the two states that have legalized marijuana for recreational use, illicit dealers have suffered now that their lucrative underground market has all but disappeared, and as a result, prices have fallen sharply (they cannot compete with the genuine, professionally grown and superior quality crop, the price of which they also cannot compete with). Buyers from nearby states have further damaged the illegal market, putting several thousands of illegal dealers out of business.

The

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction reports that typical retail prices in Europe for cannabis varies from €2 to €20 per gram, with a majority of European countries reporting prices in the range €4–10.

[111]

History

Cannabis is

indigenous to Central and South Asia.

[114] Evidence of the inhalation of cannabis smoke can be found in the 3rd millennium BCE, as indicated by charred cannabis seeds found in a ritual

brazier at an ancient

burial site in present day Romania.

[115] In 2003, a leather basket filled with cannabis leaf fragments and seeds was found next to a 2,500- to 2,800-year-old

mummified shaman in the northwestern

Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China.

[116][117] Evidence for the consumption of cannabis has also been found in Egyptian mummies dated about 950 BC.

[118][119]

Cannabis is also known to have been used by the ancient Hindus of India and Nepal thousands of years ago. The herb was called

ganjika in

Sanskrit (गांजा,

ganja in modern

Indo-Aryan languages).

[120][121] Some scholars suggest that the ancient drug

soma, mentioned in the

Vedas, was cannabis, although this theory is disputed.

[122]

Cannabis was also known to the

ancient Assyrians, who discovered its psychoactive properties through the

Aryans.

[123] Using it in some religious ceremonies, they called it

qunubu (meaning "way to produce smoke"), a probable origin of the modern word "cannabis".

[124] Cannabis was also introduced by the Aryans to the

Scythians,

Thracians and

Dacians, whose

shamans (the

kapnobatai—"those who walk on smoke/clouds") burned cannabis flowers to induce a state of

trance.

[125]

Cannabis has an ancient history of ritual use and is found in

pharmacological cults around the world. Hemp seeds discovered by archaeologists at

Pazyryk suggest early ceremonial practices like eating by the Scythians occurred during the 5th to 2nd century BCE, confirming previous historical reports by

Herodotus.

[126] It was used by Muslims in various

Sufi orders as early as the

Mamluk period, for example by the

Qalandars.

[127]

A study published in the

South African Journal of Science showed that "pipes dug up from the garden of

Shakespeare's home in

Stratford-upon-Avon contain traces of cannabis."

[128] The chemical analysis was carried out after researchers hypothesized that the "noted weed" mentioned in

Sonnet 76 and the "journey in my head" from

Sonnet 27 could be references to cannabis and the use thereof.

[129] Examples of classic literature featuring cannabis include

Les paradis artificiels by

Charles Baudelaire and

The Hasheesh Eater by

Fitz Hugh Ludlow.

John Gregory Bourke described use of "mariguan", which he identifies as

Cannabis indica or Indian hemp, by Mexican residents of the

Rio Grande region of

Texas in 1894. He described its uses for treatment of asthma, to expedite delivery, to keep away witches, and as a love-philtre. He also wrote that many Mexicans added the herb to their cigarritos or mescal, often taking a bite of sugar afterward to intensify the effect. Bourke wrote that because it was often used in a mixture with

toloachi (which he inaccurately describes as

Datura stramonium), mariguan was one of several plants known as "

loco weed". Bourke compared mariguan to hasheesh, which he called "one of the greatest curses of the East", citing reports that users "become maniacs and are apt to commit all sorts of acts of violence and murder", causing degeneration of the body and an idiotic appearance, and mentioned laws against sale of hasheesh "in most Eastern countries".

[130][131][132]

Cannabis indica fluid extract, American Druggists Syndicate, pre-1937

Cannabis was criminalized in various countries beginning in the early 20th century. In the United States, the first restrictions for sale of cannabis came in 1906 (in

District of Columbia).

[133] It was outlawed in South Africa in 1911, in

Jamaica (then a British colony) in 1913, and in the United Kingdom and New Zealand in the 1920s.

[134] Canada criminalized cannabis in the Opium and Drug Act of 1923, before any reports of use of the drug in Canada. In 1925 a compromise was made at an international conference in

The Hague about the

International Opium Convention that banned exportation of "Indian hemp" to countries that had prohibited its use, and requiring importing countries to issue certificates approving the importation and stating that the shipment was required "exclusively for medical or scientific purposes". It also required parties to "exercise an effective control of such a nature as to prevent the illicit international traffic in Indian hemp and especially in the resin".

[135][136]

In the United States in 1937, the

Marihuana Tax Act was passed, and prohibited the production of hemp in addition to cannabis. The reasons that hemp was also included in this law are disputed—several scholars have claimed that the act was passed in order to destroy the US hemp industry,

[137][138][139] with the primary involvement of businessmen

Andrew Mellon,

Randolph Hearst, and the

Du Pont family.

[137][139] But the improvements of the

decorticators, machines that separate the fibers from the hemp stem, could not make hemp fiber a very cheap substitute for fibers from other sources because it could not change that basic fact that strong fibers are only found in the bast, the outer part of the stem. Only about 1/3 of the stem are long and strong fibers.

[137][140][141][142]The company DuPont and many industrial historians dispute a link between

nylon and hemp. They argue that the purpose of developing the nylon was to produce a fiber that could be used in thin stockings for females and compete with

silk.

[143][144][145]

In New York City, more than 41,000 pounds of marijuana, which was growing like weeds throughout the boroughs until 1951, when the "White Wing Squad", headed by the Sanitation Department General Inspector John E. Gleason, was charged with destroying the many pot farms that had sprouted up across the city. The

Brooklyn Public Library reports: this group was held to a high moral standard and was prohibited from "entering saloons, using foul language, and neglecting horses." The Squad found the most weed in Queens but even in Brooklyn dug up "millions of dollars" worth of the plants, many as "tall as Christmas trees". Gleason oversaw incineration of the plants in

Woodside, Queens.

[146]

The United Nations' 2012

Global Drug Report stated that cannabis "was the world's most widely produced, trafficked, and consumed drug in the world in 2010", identifying that between 119 million and 224 million users existed in the world's adult (18 or older) population.

[147]

Medical marijuana

Medical marijuana refers to the use of the

Cannabis plant as a physician-recommended

herbal therapy as well as synthetic THC and cannabinoids. So far, the medical use of cannabis is legal only in a limited number of territories, including

Canada,

Belgium,

Australia, the

Netherlands,

Spain, and

several U.S. states. This usage generally requires a prescription, and distribution is usually done within a framework defined by local laws.

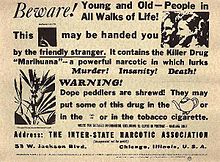

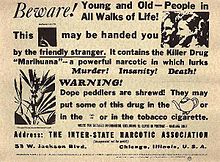

Legal status

Cannabis propaganda sheet from 1935

Since the beginning of the 20th century, most countries have enacted

laws against the cultivation, possession or transfer of cannabis.

[148] These laws have impacted adversely on the cannabis plant's cultivation for non-recreational purposes, but there are many regions where, under certain circumstances, handling of cannabis is legal or licensed. Many jurisdictions have lessened the penalties for possession of small quantities of cannabis, so that it is punished by confiscation and sometimes a fine, rather than imprisonment, focusing more on those who

traffic the drug on the

black market.

In some areas where cannabis use has been historically tolerated, some new restrictions have been put in place, such as the closing of

cannabis coffee shops near the borders of the Netherlands,

[149] closing of coffee shops near secondary schools in the Netherlands and crackdowns on "Pusher Street" in

Christiania,

Copenhagen in 2004.

[150][151]

Some jurisdictions use free voluntary treatment programs and/or mandatory treatment programs for frequent known users. Simple possession can carry long prison terms in some countries, particularly in East Asia, where the sale of cannabis may lead to a sentence of life in prison or even execution. More recently however, many political parties, non-profit organizations and causes based on the legalization of medical cannabis and/or legalizing the plant entirely (with some restrictions) have emerged.

In December 2012, the U.S. state of

Washington became the first state to officially legalize cannabis in a state law (

Washington Initiative 502) (but still illegal by

federal law),

[152] with the state of

Colorado following close behind (

Colorado Amendment 64).

[153] On January 1, 2013, the first marijuana "club" for private marijuana smoking (no buying or selling, however) was allowed for the first time in Colorado.

[154] The California Supreme Court decided in May 2013 that local governments can ban medical marijuana dispensaries despite a state law in California that permits the use of cannabis for medical purposes. At least 180 cities across California have enacted bans in recent years.

[155]

In December 2013,

Uruguay became the first country to legalize growing, sale and use of cannabis.

[156] However, as of August 2014, no cannabis has yet been sold legally in Uruguay. According to the law, the only cannabis that can be sold legally must be grown in the country by no more than five licensed growers, and these have yet to be selected; in fact the call for applications did not go out until August 1, 2014.

[157] In the elections of October, 2014, there is a significant chance that lawmakers opposed to legal cannabis will come to control the legislature, and the law will be repealed before it has fully taken effect.

[158][159][160]

Constraints on open research

Cannabis research is challenging since the plant is illegal in most countries.

[161][162][163][164][165] Research-grade samples of the drug are difficult to obtain for research purposes, unless granted under authority of national governments.

There are also other difficulties in researching the effects of cannabis. Many people who smoke cannabis also smoke tobacco.

[166] This causes confounding factors, where questions arise as to whether the tobacco, the cannabis, or both that have caused a cancer. Another difficulty researchers have is in recruiting people who smoke cannabis into studies. Because cannabis is an illegal drug in many countries, people may be reluctant to take part in research, and if they do agree to take part, they may not say how much cannabis they actually smoke.

[167]

However many universities in different countries outside the US have published hundreds of studies on effects of cannabis.

[168]

and

and  , and the sentence is given by

, and the sentence is given by  , involving the logical connectives for

, involving the logical connectives for  from an observed surprising circumstance

from an observed surprising circumstance  is to surmise that

is to surmise that