From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Atmospheric chemistry is a branch of atmospheric science in which the chemistry of the Earth's atmosphere and that of other planets is studied. It is a multidisciplinary field of research and draws on environmental chemistry, physics, meteorology, computer modeling, oceanography, geology and volcanology and other disciplines. Research is increasingly connected with other areas of study such as climatology.

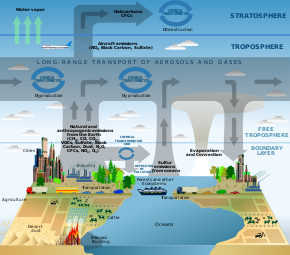

The composition and chemistry of the atmosphere is of importance for several reasons, but primarily because of the interactions between the atmosphere and living organisms. The composition of the Earth's atmosphere changes as result of natural processes such as volcano emissions, lightning and bombardment by solar particles from corona. It has also been changed by human activity and some of these changes are harmful to human health, crops and ecosystems. Examples of problems which have been addressed by atmospheric chemistry include acid rain, ozone depletion, photochemical smog, greenhouse gases and global warming. Atmospheric chemists seek to understand the causes of these problems, and by obtaining a theoretical understanding of them, allow possible solutions to be tested and the effects of changes in government policy evaluated.

Notes: the concentration of CO2 and CH4 vary by season and location. The mean molecular mass of air is 28.97 g/mol.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries interest shifted towards trace constituents with very small concentrations. One particularly important discovery for atmospheric chemistry was the discovery of ozone by Christian Friedrich Schönbein in 1840.

In the 20th century atmospheric science moved on from studying the composition of air to a consideration of how the concentrations of trace gases in the atmosphere have changed over time and the chemical processes which create and destroy compounds in the air. Two particularly important examples of this were the explanation by Sydney Chapman and Gordon Dobson of how the ozone layer is created and maintained, and the explanation of photochemical smog by Arie Jan Haagen-Smit. Further studies on ozone issues led to the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry award shared between Paul Crutzen, Mario Molina and Frank Sherwood Rowland.[2]

In the 21st century the focus is now shifting again. Atmospheric chemistry is increasingly studied as one part of the Earth system. Instead of concentrating on atmospheric chemistry in isolation the focus is now on seeing it as one part of a single system with the rest of the atmosphere, biosphere and geosphere. An especially important driver for this is the links between chemistry and climate such as the effects of changing climate on the recovery of the ozone hole and vice versa but also interaction of the composition of the atmosphere with the oceans and terrestrial ecosystems.

Some models are constructed by automatic code generators (e.g. Autochem or KPP). In this approach a set of constituents are chosen and the automatic code generator will then select the reactions involving those constituents from a set of reaction databases. Once the reactions have been chosen the ordinary differential equations (ODE) that describe their time evolution can be automatically constructed.

The composition and chemistry of the atmosphere is of importance for several reasons, but primarily because of the interactions between the atmosphere and living organisms. The composition of the Earth's atmosphere changes as result of natural processes such as volcano emissions, lightning and bombardment by solar particles from corona. It has also been changed by human activity and some of these changes are harmful to human health, crops and ecosystems. Examples of problems which have been addressed by atmospheric chemistry include acid rain, ozone depletion, photochemical smog, greenhouse gases and global warming. Atmospheric chemists seek to understand the causes of these problems, and by obtaining a theoretical understanding of them, allow possible solutions to be tested and the effects of changes in government policy evaluated.

Atmospheric composition

Visualisation of composition by volume of Earth's atmosphere. Water vapour is not included as it is highly variable. Each tiny cube (such as the one representing krypton) has one millionth of the volume of the entire block. Data is from NASA Langley.

| Average composition of dry atmosphere (mole fractions) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gas | per NASA | |

| Nitrogen, N2 | 78.084% | |

| Oxygen, O2[1] | 20.946% | |

| Minor constituents (mole fractions in ppm) | ||

| Argon, Ar | 9340 | |

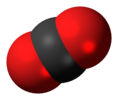

| Carbon dioxide, CO2 | 400 | |

| Neon, Ne | 18.18 | |

| Helium, He | 5.24 | |

| Methane, CH4 | 1.7 | |

| Krypton, Kr | 1.14 | |

| Hydrogen, H2 | 0.55 | |

| Water | ||

| Water vapour | Highly variable; typically makes up about 1% |

|

History

The ancient Greeks regarded air as one of the four elements, but the first scientific studies of atmospheric composition began in the 18th century. Chemists such as Joseph Priestley, Antoine Lavoisier and Henry Cavendish made the first measurements of the composition of the atmosphere.In the late 19th and early 20th centuries interest shifted towards trace constituents with very small concentrations. One particularly important discovery for atmospheric chemistry was the discovery of ozone by Christian Friedrich Schönbein in 1840.

In the 20th century atmospheric science moved on from studying the composition of air to a consideration of how the concentrations of trace gases in the atmosphere have changed over time and the chemical processes which create and destroy compounds in the air. Two particularly important examples of this were the explanation by Sydney Chapman and Gordon Dobson of how the ozone layer is created and maintained, and the explanation of photochemical smog by Arie Jan Haagen-Smit. Further studies on ozone issues led to the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry award shared between Paul Crutzen, Mario Molina and Frank Sherwood Rowland.[2]

In the 21st century the focus is now shifting again. Atmospheric chemistry is increasingly studied as one part of the Earth system. Instead of concentrating on atmospheric chemistry in isolation the focus is now on seeing it as one part of a single system with the rest of the atmosphere, biosphere and geosphere. An especially important driver for this is the links between chemistry and climate such as the effects of changing climate on the recovery of the ozone hole and vice versa but also interaction of the composition of the atmosphere with the oceans and terrestrial ecosystems.

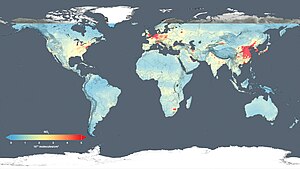

Carbon dioxide in Earth's atmosphere if half of global-warming emissions[3][4] are not absorbed.

(NASA simulation; 9 November 2015)

(NASA simulation; 9 November 2015)

Methodology

Observations, lab measurements and modeling are the three central elements in atmospheric chemistry. Progress in atmospheric chemistry is often driven by the interactions between these components and they form an integrated whole. For example, observations may tell us that more of a chemical compound exists than previously thought possible. This will stimulate new modelling and laboratory studies which will increase our scientific understanding to a point where the observations can be explained.Observation

Observations of atmospheric chemistry are essential to our understanding. Routine observations of chemical composition tell us about changes in atmospheric composition over time. One important example of this is the Keeling Curve - a series of measurements from 1958 to today which show a steady rise in of the concentration of carbon dioxide. Observations of atmospheric chemistry are made in observatories such as that on Mauna Loa and on mobile platforms such as aircraft (e.g. the UK's Facility for Airborne Atmospheric Measurements), ships and balloons. Observations of atmospheric composition are increasingly made by satellites with important instruments such as GOME and MOPITT giving a global picture of air pollution and chemistry. Surface observations have the advantage that they provide long term records at high time resolution but are limited in the vertical and horizontal space they provide observations from. Some surface based instruments e.g. LIDAR can provide concentration profiles of chemical compounds and aerosol but are still restricted in the horizontal region they can cover. Many observations are available on line in Atmospheric Chemistry Observational Databases.Lab measurements

Measurements made in the laboratory are essential to our understanding of the sources and sinks of pollutants and naturally occurring compounds. Lab studies tell us which gases react with each other and how fast they react. Measurements of interest include reactions in the gas phase, on surfaces and in water. Also of high importance is photochemistry which quantifies how quickly molecules are split apart by sunlight and what the products are plus thermodynamic data such as Henry's law coefficients.Modeling

In order to synthesise and test theoretical understanding of atmospheric chemistry, computer models (such as chemical transport models) are used. Numerical models solve the differential equations governing the concentrations of chemicals in the atmosphere. They can be very simple or very complicated. One common trade off in numerical models is between the number of chemical compounds and chemical reactions modelled versus the representation of transport and mixing in the atmosphere. For example, a box model might include hundreds or even thousands of chemical reactions but will only have a very crude representation of mixing in the atmosphere. In contrast, 3D models represent many of the physical processes of the atmosphere but due to constraints on computer resources will have far fewer chemical reactions and compounds. Models can be used to interpret observations, test understanding of chemical reactions and predict future concentrations of chemical compounds in the atmosphere. One important current trend is for atmospheric chemistry modules to become one part of earth system models in which the links between climate, atmospheric composition and the biosphere can be studied.Some models are constructed by automatic code generators (e.g. Autochem or KPP). In this approach a set of constituents are chosen and the automatic code generator will then select the reactions involving those constituents from a set of reaction databases. Once the reactions have been chosen the ordinary differential equations (ODE) that describe their time evolution can be automatically constructed.

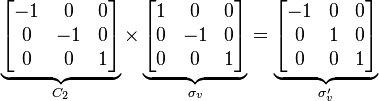

results in a molecule indistinguishable from the original. This is also called an n-fold rotational axis and abbreviated Cn. Examples are the C2 in

results in a molecule indistinguishable from the original. This is also called an n-fold rotational axis and abbreviated Cn. Examples are the C2 in