From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Vanadium, 23V

|

| Vanadium |

|---|

| Pronunciation | (və-NAY-dee-əm) |

|---|

| Appearance | blue-silver-grey metal |

|---|

| Standard atomic weight Ar, std(V) | 50.9415(1) |

|---|

| Vanadium in the periodic table |

|---|

|

|

| Atomic number (Z) | 23 |

|---|

| Group | group 5 |

|---|

| Period | period 4 |

|---|

| Block | d-block |

|---|

| Element category | transition metal |

|---|

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d3 4s2 |

|---|

Electrons per shell

| 2, 8, 11, 2 |

|---|

| Physical properties |

|---|

| Phase at STP | solid |

|---|

| Melting point | 2183 K (1910 °C, 3470 °F) |

|---|

| Boiling point | 3680 K (3407 °C, 6165 °F) |

|---|

| Density (near r.t.) | 6.0 g/cm3 |

|---|

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 5.5 g/cm3 |

|---|

| Heat of fusion | 21.5 kJ/mol |

|---|

| Heat of vaporization | 444 kJ/mol |

|---|

| Molar heat capacity | 24.89 J/(mol·K) |

|---|

Vapor pressure

| P (Pa)

|

1

|

10

|

100

|

1 k

|

10 k

|

100 k

|

| at T (K)

|

2101

|

2289

|

2523

|

2814

|

3187

|

3679

|

|

| Atomic properties |

|---|

| Oxidation states | −3, −1, +1, +2, +3, +4, +5 (an amphoteric oxide) |

|---|

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.63 |

|---|

| Ionization energies |

- 1st: 650.9 kJ/mol

- 2nd: 1414 kJ/mol

- 3rd: 2830 kJ/mol

- (more)

|

|---|

| Atomic radius | empirical: 134 pm |

|---|

| Covalent radius | 153±8 pm |

|---|

|

Spectral lines of vanadium |

| Other properties |

|---|

| Natural occurrence | primordial |

|---|

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic (bcc)

|

|---|

| Speed of sound thin rod | 4560 m/s (at 20 °C) |

|---|

| Thermal expansion | 8.4 µm/(m·K) (at 25 °C) |

|---|

| Thermal conductivity | 30.7 W/(m·K) |

|---|

| Electrical resistivity | 197 nΩ·m (at 20 °C) |

|---|

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic |

|---|

| Magnetic susceptibility | +255.0·10−6 cm3/mol (298 K) |

|---|

| Young's modulus | 128 GPa |

|---|

| Shear modulus | 47 GPa |

|---|

| Bulk modulus | 160 GPa |

|---|

| Poisson ratio | 0.37 |

|---|

| Mohs hardness | 6.7 |

|---|

| Vickers hardness | 628–640 MPa |

|---|

| Brinell hardness | 600–742 MPa |

|---|

| CAS Number | 7440-62-2 |

|---|

| History |

|---|

| Discovery | Andrés Manuel del Río (1801) |

|---|

| First isolation | Nils Gabriel Sefström (1830) |

|---|

| Named by | Nils Gabriel Sefström (1830) |

|---|

| Main isotopes of vanadium |

|---|

|

|

Vanadium is a

chemical element with the

symbol V and

atomic number 23. It is a hard, silvery-grey,

ductile,

malleable transition metal. The elemental metal is rarely found in nature, but once isolated artificially, the formation of an

oxide layer (

passivation) somewhat stabilizes the free metal against further

oxidation.

Andrés Manuel del Río discovered compounds of vanadium in 1801 in

Mexico by analyzing a new

lead-bearing mineral he called "brown lead", and presumed its qualities were due to the presence of a new element, which he named

erythronium (derived from "

ἐρυθρόν",

greek word for "red") since upon heating most of the

salts turned red. Four years later, he was (erroneously) convinced by other scientists that erythronium was identical to

chromium.

Chlorides of vanadium were generated in 1830 by

Nils Gabriel Sefström

who thereby proved that a new element was involved, which he named

"vanadium" after the Scandinavian goddess of beauty and fertility,

Vanadís (

Freyja). Both names were attributed to the wide range of colors found in vanadium compounds. Del Rio's lead mineral was later renamed

vanadinite for its vanadium content. In 1867

Henry Enfield Roscoe obtained the pure element.

Vanadium occurs naturally in about 65

minerals and in

fossil fuel deposits. It is produced in

China and

Russia from steel smelter

slag. Other countries produce it either from magnetite directly, flue dust of heavy oil, or as a byproduct of

uranium mining. It is mainly used to produce specialty

steel alloys such as

high-speed tool steels. The most important industrial vanadium compound,

vanadium pentoxide, is used as a catalyst for the production of

sulfuric acid. The

vanadium redox battery for energy storage may be an important application in the future.

Large amounts of vanadium

ions are found in a few organisms, possibly as a

toxin.

The oxide and some other salts of vanadium have moderate toxicity.

Particularly in the ocean, vanadium is used by some life forms as an

active center of

enzymes, such as the

vanadium bromoperoxidase of some ocean

algae.

History

Vanadium was

discovered by

Andrés Manuel del Río, a Spanish-Mexican mineralogist, in 1801. Del Río extracted the element from a sample of Mexican "brown lead" ore, later named

vanadinite. He found that its salts exhibit a wide variety of colors, and as a result he named the element

panchromium (Greek: παγχρώμιο "all colors"). Later, Del Río renamed the element

erythronium (Greek: ερυθρός "red") because most of the salts turned red upon heating. In 1805, French chemist

Hippolyte Victor Collet-Descotils, backed by del Río's friend Baron

Alexander von Humboldt, incorrectly declared that del Río's new element was only an impure sample of

chromium. Del Río accepted Collet-Descotils' statement and retracted his claim.

In 1831, Swedish chemist

Nils Gabriel Sefström rediscovered the element in a new oxide he found while working with

iron ores. Later that year,

Friedrich Wöhler confirmed del Río's earlier work. Sefström chose a name beginning with V, which had not yet been assigned to any element. He called the element

vanadium after

Old Norse Vanadís (another name for the

Norse Vanr goddess

Freyja, whose attributes include beauty and fertility), because of the many beautifully colored

chemical compounds it produces. In 1831, the geologist

George William Featherstonhaugh suggested that vanadium should be renamed "

rionium" after del Río, but this suggestion was not followed.

The first large-scale industrial use of vanadium was in the

steel alloy chassis of the

Ford Model T, inspired by French race cars. Vanadium steel allowed reduced weight while increasing

tensile strength (ca. 1905).

[8] For the first decade of the 20

th century, most vanadium ore was mined by

American Vanadium Company from the

Minas Ragra in Peru. Later the demand for uranium rose, leading to increased mining of that metal's ores. One major uranium ore was

carnotite,

which also contains vanadium. Thus, vanadium became available as a

by-product of uranium production. Eventually uranium mining began to

supply a large share of the demand for vanadium.

Characteristics

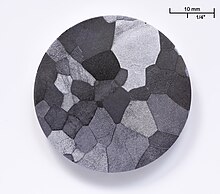

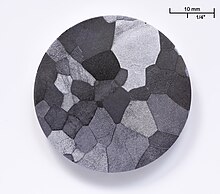

High-purity (99.95%) vanadium cuboids, ebeam remelted and macro-etched

Isotopes

Naturally occurring vanadium is composed of one stable

isotope,

51V, and one radioactive isotope,

50V. The latter has a

half-life of 1.5×10

17 years and a natural abundance of 0.25%.

51V has a

nuclear spin of

7⁄2, which is useful for

NMR spectroscopy. Twenty-four artificial

radioisotopes have been characterized, ranging in

mass number from 40 to 65. The most stable of these isotopes are

49V with a half-life of 330 days, and

48V with a half-life of 16.0 days. The remaining

radioactive isotopes have half-lives shorter than an hour, most below 10 seconds. At least four isotopes have

metastable excited states.

Electron capture is the main

decay mode for isotopes lighter than

51V. For the heavier ones, the most common mode is

beta decay. The electron capture reactions lead to the formation of element 22 (

titanium) isotopes, while beta decay leads to element 24 (

chromium) isotopes.

Chemistry

From left: [V(H2O)6]2+ (lilac), [V(H2O)6]3+ (green), [VO(H2O)5]2+ (blue) and [VO(H2O)5]3+ (yellow).

The chemistry of vanadium is noteworthy for the accessibility of the four adjacent

oxidation states 2–5. In

aqueous solution, vanadium forms

metal aquo complexes of which the colours are lilac [V(H

2O)

6]

2+, green [V(H

2O)

6]

3+, blue [VO(H

2O)

5]

2+, yellow VO

3−.

Vanadium(II) compounds are reducing agents, and vanadium(V) compounds

are oxidizing agents. Vanadium(IV) compounds often exist as

vanadyl derivatives, which contain the VO

2+ center.

Ammonium vanadate(V) (NH

4VO

3) can be successively reduced with elemental

zinc

to obtain the different colors of vanadium in these four oxidation

states. Lower oxidation states occur in compounds such as V(CO)

6,

[V(CO)

6]− and substituted derivatives.

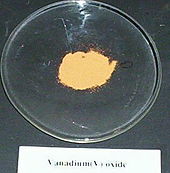

The most commercially important compound is

vanadium pentoxide. It is used as a catalyst for the production of sulfuric acid. This compound oxidizes

sulfur dioxide (

SO

2) to the

trioxide (

SO

3). In this

redox reaction, sulfur is oxidized from +4 to +6, and vanadium is reduced from +5 to +4:

- V2O5 + SO2 → 2 VO2 + SO3

The catalyst is regenerated by oxidation with air:

- 4 VO2 + O2 → 2 V2O5

The

vanadium redox battery

utilizes all four oxidation states: one electrode uses the +5/+4 couple

and the other uses the +3/+2 couple. Conversion of these oxidation

states is illustrated by the reduction of a strongly acidic solution of a

vanadium(V) compound with zinc dust or amalgam. The initial yellow

color characteristic of the pervanadyl ion [VO

2(H

2O)

4]

+ is replaced by the blue color of [VO(H

2O)

5]

2+, followed by the green color of [V(H

2O)

6]

3+ and then the violet color of [V(H

2O)

6]

2+.

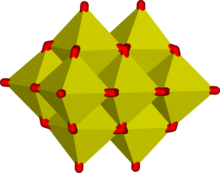

Oxyanions

In aqueous solution, vanadium(V) forms an extensive family of

oxyanions. The interrelationships in this family are described by the

predominance diagram, which shows at least 11 species, depending on pH and concentration. The tetrahedral orthovanadate ion,

VO3−

4,

is the principal species present at pH 12-14. Similar in size and

charge to phosphorus(V), vanadium(V) also parallels its chemistry and

crystallography.

Orthovanadate V

O3−

4 is used in

protein crystallography to study the

biochemistry of phosphate. The tetrathiovanadate [VS

4]

3− is analogous to the orthovanadate ion.

At lower pH values, the monomer [HVO

4]

2− and dimer [V

2O

7]

− are formed, with the monomer predominant at vanadium concentration of less than c. 10

−2M

(pV > 2, where pV is equal to the minus value of the logarithm of

the total vanadium concentration/M). The formation of the divanadate ion

is analogous to the formation of the

dichromate ion. As the pH is reduced, further protonation and condensation to

polyvanadates occur: at pH 4-6 [H

2VO

4]

− is predominant at pV greater than ca. 4, while at higher concentrations trimers and tetramers are formed. Between pH 2-4

decavanadate predominates, its formation from orthovanadate is represented by this condensation reaction:

- 10 [VO4]3− + 24 H+ → [V10O28]6− + 12 H2O

In decavanadate, each V(V) center is surrounded by six oxide

ligands. Vanadic acid, H

3VO

4 exists only at very low concentrations because protonation of the tetrahedral species [H

2VO

4]

− results in the preferential formation of the octahedral [VO

2(H

2O)

4]

+ species. In strongly acidic solutions, pH<2 .="" sub="">2

(H

2O)

4]

+ is the predominant species, while the oxide V

2O

5 precipitates from solution at high concentrations. The oxide is formally the

acid anhydride of vanadic acid. The structures of many

vanadate compounds have been determined by X-ray crystallography.

The

Pourbaix diagram for vanadium in water, which shows the

redox potentials between various vanadium species in different oxidation states, is also complex.

Vanadium(V) forms various peroxo complexes, most notably in the active site of the vanadium-containing

bromoperoxidase enzymes. The species VO(O)

2(H

2O)

4+

is stable in acidic solutions. In alkaline solutions, species with 2, 3

and 4 peroxide groups are known; the last forms violet salts with the

formula M

3V(O

2)

4 nH

2O (M= Li, Na, etc.), in which the vanadium has an 8-coordinate dodecahedral structure.

Halide derivatives

Twelve binary

halides, compounds with the formula VX

n (n=2..5), are known. VI

4, VCl

5, VBr

5, and VI

5 do not exist or are extremely unstable. In combination with other reagents,

VCl4 is used as a catalyst for polymerization of

dienes. Like all binary halides, those of vanadium are

Lewis acidic, especially those of V(IV) and V(V). Many of the halides form octahedral complexes with the formula VX

nL

6−n (X= halide; L= other ligand).

Many vanadium

oxyhalides (formula VO

mX

n) are known. The oxytrichloride and oxytrifluoride (

VOCl3 and

VOF3) are the most widely studied. Akin to POCl

3, they are volatile, adopt tetrahedral structures in the gas phase, and are Lewis acidic.

Coordination compounds

Complexes of vanadium(II) and (III) are relatively exchange inert and

reducing. Those of V(IV) and V(V) are oxidants. Vanadium ion is rather

large and some complexes achieve coordination numbers greater than 6, as

is the case in [V(CN)

7]

4−. Oxovanadium(V) also

forms 7 coordinate coordination complexes with tetradentate ligands and

peroxides and these complexes are used for oxidative brominations and

thioether oxidations. The coordination chemistry of V

4+ is dominated by the

vanadyl center, VO

2+, which binds four other ligands strongly and one weakly (the one trans to the vanadyl center). An example is

vanadyl acetylacetonate (V(O)(O

2C

5H

7)

2).

In this complex, the vanadium is 5-coordinate, square pyramidal,

meaning that a sixth ligand, such as pyridine, may be attached, though

the

association constant of this process is small. Many 5-coordinate vanadyl complexes have a trigonal bipyramidal geometry, such as VOCl

2(NMe

3)

2. The coordination chemistry of V

5+

is dominated by the relatively stable dioxovanadium coordination

complexes which are often formed by aerial oxidation of the vanadium(IV)

precursors indicating the stability of the +5 oxidation state and ease

of interconversion between the +4 and +5 states.

Organometallic compounds

Organometallic chemistry of vanadium is well developed, although it has mainly only academic significance.

Vanadocene dichloride is a versatile starting reagent and even finds some applications in organic chemistry.

Vanadium carbonyl, V(CO)

6, is a rare example of a paramagnetic

metal carbonyl. Reduction yields V

(CO)−

6 (

isoelectronic with

Cr(CO)6), which may be further reduced with sodium in liquid ammonia to yield V

(CO)3−

5 (isoelectronic with Fe(CO)

5).

Occurrence

Universe

Earth's crust

Vanadium is the 20th most abundant element in the earth's crust; metallic vanadium is rare in nature (known as the mineral vanadium,

native vanadium), but vanadium compounds occur naturally in about 65 different

minerals.

At the beginning of the 20th century a large deposit of vanadium ore was discovered. For several years this

patrónite (VS

4) deposit was a economically significant source for vanadium ore. With the production of radium in the 1910s and 1920s from

carnotite (

K2(UO2)2(VO4)2·3H2O) vanadium became available as a side product of radium and uranium production.

Vanadinite (

Pb5(VO4)3Cl)

and other vanadium bearing minerals are only mined in exceptional

cases. With the rising demand, much of the world's vanadium production

is now sourced from vanadium-bearing

magnetite found in

ultramafic gabbro bodies. If this

titanomagnetite is used to produce iron, most of the vanadium goes to the

slag, and is extracted from it.

Vanadium is mined mostly in

South Africa, north-western

China, and eastern

Russia. In 2013 these three countries mined more than 97% of the 79,000

tonnes of produced vanadium.

Vanadium is also present in

bauxite and in deposits of

crude oil,

coal,

oil shale, and

tar sands.

In crude oil, concentrations up to 1200 ppm have been reported. When

such oil products are burned, traces of vanadium may cause

corrosion in engines and boilers. An estimated 110,000 tonnes of vanadium per year are released into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels.

Water

Production

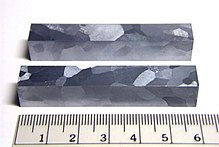

Vacuum sublimed vanadium dendritic crystals (99.9%)

Crystal-bar vanadium, showing different textures and surface oxidation; 99.95%-pure cube for comparison

Vanadium metal is obtained by a multistep process that begins with roasting crushed ore with

NaCl or

Na2CO3 at about 850 °C to give

sodium metavanadate (NaVO

3). An aqueous extract of this solid is acidified to produce "red cake", a polyvanadate salt, which is reduced with

calcium metal. As an alternative for small-scale production, vanadium pentoxide is reduced with

hydrogen or

magnesium. Many other methods are also used, in all of which vanadium is produced as a

byproduct of other processes. Purification of vanadium is possible by the

crystal bar process developed by

Anton Eduard van Arkel and

Jan Hendrik de Boer in 1925. It involves the formation of the metal iodide, in this example

vanadium(III) iodide, and the subsequent decomposition to yield pure metal:

- 2 V + 3 I2 ⇌ 2 VI3

Most vanadium is used as a

steel alloy called

ferrovanadium.

Ferrovanadium is produced directly by reducing a mixture of vanadium

oxide, iron oxides and iron in an electric furnace. The vanadium ends up

in

pig iron produced from vanadium-bearing magnetite. Depending on the ore used, the slag contains up to 25% of vanadium.

Applications

Tool made from vanadium steel

Alloys

Approximately 85% of the vanadium produced is used as

ferrovanadium or as a

steel additive.

The considerable increase of strength in steel containing small amounts

of vanadium was discovered in the early 20th century. Vanadium forms

stable nitrides and carbides, resulting in a significant increase in the

strength of steel. From that time on, vanadium steel was used for applications in

axles, bicycle frames,

crankshafts,

gears, and other critical components. There are two groups of vanadium

steel alloys. Vanadium high-carbon steel alloys contain 0.15% to 0.25%

vanadium, and

high-speed tool steels (HSS) have a vanadium content of 1% to 5%. For high-speed tool steels, a hardness above

HRC 60 can be achieved. HSS steel is used in

surgical instruments and

tools.

Powder-metallurgic

alloys contain up to 18% percent vanadium. The high content of vanadium

carbides in those alloys increases wear resistance significantly. One

application for those alloys is tools and knives.

Vanadium stabilizes the beta form of titanium and increases the strength and temperature stability of titanium. Mixed with

aluminium in

titanium alloys, it is used in

jet engines, high-speed airframes and

dental implants. The most common alloy for seamless tubing is

Titanium 3/2.5 containing 2.5% vanadium, the titanium alloy of choice in the aerospace, defense, and bicycle industries. Another common alloy, primarily produced in sheets, is

Titanium 6AL-4V, a titanium alloy with 6% aluminium and 4% vanadium.

Several vanadium alloys show superconducting behavior. The first

A15 phase superconductor was a vanadium compound, V

3Si, which was discovered in 1952.

Vanadium-gallium tape is used in

superconducting magnets (17.5

teslas or 175,000

gauss). The structure of the superconducting A15 phase of V

3Ga is similar to that of the more common

Nb3Sn and

Nb3Ti.

It has been proposed that a small amount, 40 to 270 ppm, of vanadium in

Wootz steel and

Damascus steel significantly improved the strength of the product, though the source of the vanadium is unclear.

Other uses

Vanadium compounds are used extensively as catalysts; for example, the most common oxide of vanadium,

vanadium pentoxide V

2O

5, is used as a

catalyst in manufacturing sulfuric acid by the

contact process and as an oxidizer in

maleic anhydride production. Vanadium pentoxide is used in

ceramics.

Vanadium is an important component of mixed metal oxide catalysts used

in the oxidation of propane and propylene to acrolein, acrylic acid or

the ammoxidation of propylene to acrylonitrile.

In service, the oxidation state of vanadium changes dynamically and

reversibly with the oxygen and the steam content of the reacting feed

mixture. Another oxide of vanadium,

vanadium dioxide VO

2, is used in the production of glass coatings, which blocks

infrared radiation (and not visible light) at a specific temperature. Vanadium oxide can be used to induce color centers in

corundum to create simulated

alexandrite jewelry, although alexandrite in nature is a

chrysoberyl.

The

Vanadium redox battery, a type of

flow battery, is an electrochemical cell consisting of aqueous vanadium ions in different oxidation states.

Batteries of the type were first proposed in the 1930s and developed

commercially from the 1980s onwards. Cells use +5 and +2 formal

oxidization state ions.

Vanadium redox batteries are used commercially for

grid energy storage.

Proposed

Biological role

Vanadium is more important in marine environments than terrestrial.

Vanadoenzymes

- R-H + Br− + H2O2 → R-Br + H2O + OH−

Vanadium accumulation in tunicates and ascidians

Vanadium is essential to

ascidians and

tunicates, where it is stored in the highly acidified

vacuoles of certain blood cell types, designated "vanadocytes".

Vanabins

(vanadium binding proteins) have been identified in the cytoplasm of

such cells. The concentration of vanadium in the blood of ascidians is

as much as ten million times higher than the surrounding seawater, which normally contains 1 to 2 µg/l.

The function of this vanadium concentration system and these

vanadium-bearing proteins is still unknown, but the vanadocytes are

later deposited just under the outer surface of the tunic where they may

deter

predation.

Fungi

Amanita muscaria and related species of macrofungi accumulate vanadium (up to 500 mg/kg in dry weight). Vanadium is present in the

coordination complex amavadin in fungal fruit-bodies. The biological importance of the accumulation is unknown. Toxic or

peroxidase enzyme functions have been suggested.

Mammals

Deficiencies in vanadium result in reduced growth in rats.

The U.S. Institute of Medicine has not confirmed that vanadium is an

essential nutrient for humans, so neither a Recommended Dietary Intake

nor an Adequate Intake have been established. Dietary intake is

estimated at 6 to 18 µg/day, with less than 5% absorbed. The

Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) of dietary vanadium, beyond which adverse effects may occur, is set at 1.8 mg/day.

Research

Vanadyl

sulfate as a dietary supplement has been researched as a means of

increasing insulin sensitivity or otherwise improving glycemic control

in people who are diabetic. Some of the trials had significant treatment

effects, but were deemed as being of poor study quality. The amounts of

vanadium used in these trials (30 to 150 mg) far exceeded the safe

upper limit.

The conclusion of the systemic review was "There is no rigorous

evidence that oral vanadium supplementation improves glycaemic control

in type 2 diabetes. The routine use of vanadium for this purpose cannot

be recommended."

Safety

All vanadium compounds should be considered toxic. Tetravalent

VOSO4 has been reported to be at least 5 times more toxic than trivalent V

2O

3. The

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set an exposure limit of 0.05 mg/m

3 for vanadium pentoxide dust and 0.1 mg/m

3 for vanadium pentoxide fumes in workplace air for an 8-hour workday, 40-hour work week. The

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has recommended that 35 mg/m

3

of vanadium be considered immediately dangerous to life and health,

that is, likely to cause permanent health problems or death.

Vanadium compounds are poorly absorbed through the

gastrointestinal system. Inhalation of vanadium and vanadium compounds

results primarily in adverse effects on the respiratory system. Quantitative data are, however, insufficient to derive a subchronic or

chronic inhalation reference dose. Other effects have been reported

after oral or inhalation exposures on blood parameters, liver, neurological development, and other organs in rats.

There is little evidence that vanadium or vanadium compounds are reproductive toxins or

teratogens. Vanadium pentoxide was reported to be carcinogenic in male rats and in male and female mice by inhalation in an NTP study, although the interpretation of the results has recently been disputed. The carcinogenicity of vanadium has not been determined by the

United States Environmental Protection Agency.

Vanadium traces in

diesel fuels are the main fuel component in

high temperature corrosion. During combustion, vanadium oxidizes and reacts with sodium and sulfur, yielding

vanadate compounds with melting points as low as 530 °C, which attack the

passivation layer on steel and render it susceptible to corrosion. The solid vanadium compounds also abrade engine components.