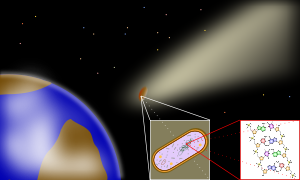

Panspermia (from Ancient Greek πᾶν (pan), meaning 'all', and σπέρμα (sperma), meaning 'seed') is the hypothesis that life exists throughout the Universe, distributed by space dust, meteoroids, asteroids, comets, planetoids, and also by spacecraft carrying unintended contamination by microorganisms. Distribution may have occurred spanning galaxies, and so may not be restricted to the limited scale of solar systems.

Panspermia hypotheses propose (for example) that microscopic life-forms that can survive the effects of space (such as extremophiles) can become trapped in debris ejected into space after collisions between planets and small Solar System bodies that harbor life. Some organisms may travel dormant for an extended amount of time before colliding randomly with other planets or intermingling with protoplanetary disks.

Under certain ideal impact circumstances (into a body of water, for

example), and ideal conditions on a new planet's surfaces, it is

possible that the surviving organisms could become active and begin to

colonize their new environment. At least one report finds that

endospores from a type of Bacillus bacteria found in Morocco can survive

being heated to 420 °C (788 °F), making the argument for Panspermia

even stronger. Panspermia studies concentrate not on how life began, but on the methods that may cause its distribution in the Universe.

Pseudo-panspermia (sometimes called "soft panspermia" or "molecular panspermia")

argues that the pre-biotic organic building-blocks of life originated

in space, became incorporated in the solar nebula from which planets

condensed, and were further—and continuously—distributed to planetary

surfaces where life then emerged (abiogenesis).

From the early 1970s, it started to become evident that interstellar

dust included a large component of organic molecules. Interstellar

molecules are formed by chemical reactions within very sparse

interstellar or circumstellar clouds of dust and gas. The dust plays a critical role in shielding the molecules from the ionizing effect of ultraviolet radiation emitted by stars.

The chemistry leading to life

may have begun shortly after the Big Bang, 13.8 billion years ago,

during a habitable epoch when the Universe was only 10 to 17 million

years old. Though the presence of life is confirmed only on the Earth,

some scientists think that extraterrestrial life is not only plausible,

but probable or inevitable. Probes and instruments have started

examining other planets and moons in the Solar System and in other

planetary systems for evidence of having once supported simple life, and

projects such as SETI attempt to detect radio transmissions from possible extraterrestrial civilizations.

History

The first known mention of the term was in the writings of the 5th-century BC Greek philosopher Anaxagoras. Panspermia began to assume a more scientific form through the proposals of Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1834), Hermann E. Richter (1865), Kelvin (1871), Hermann von Helmholtz (1879) and finally reaching the level of a detailed scientific hypothesis through the efforts of the Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius (1903).

Fred Hoyle (1915–2001) and Chandra Wickramasinghe (born 1939) were influential proponents of panspermia. In 1974 they proposed the hypothesis that some dust in interstellar space was largely organic (containing carbon), which Wickramasinghe later proved to be correct.

Hoyle and Wickramasinghe further contended that life forms continue to

enter the Earth's atmosphere, and may be responsible for epidemic

outbreaks, new diseases, and the genetic novelty necessary for macroevolution.

In an Origins Symposium presentation on April 7, 2009, physicist Stephen Hawking

stated his opinion about what humans may find when venturing into

space, such as the possibility of alien life through the theory of

panspermia: "Life could spread from planet to planet or from stellar

system to stellar system, carried on meteors."

Three series of astrobiology experiments have been conducted outside the International Space Station between 2008 and 2015 (EXPOSE) where a wide variety of biomolecules, microorganisms, and their spores were exposed to the solar flux and vacuum of space for about 1.5 years. Some organisms survived in an inactive state for considerable lengths of time,

and those samples sheltered by simulated meteorite material provide

experimental evidence for the likelihood of the hypothetical scenario of

lithopanspermia.

Several simulations in laboratories and in low Earth orbit

suggest that ejection, entry and impact is survivable for some simple

organisms. In 2015, remains of biotic material were found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia, when the young Earth was about 400 million years old. According to one researcher, "If life arose relatively quickly on Earth … then it could be common in the universe."

In April 2018, a Russian team published a paper which disclosed

that they found DNA on the exterior of the ISS from land and marine

bacteria similar to those previously observed in superficial micro

layers at the Barents and Kara seas' coastal zones. They conclude "The

presence of the wild land and marine bacteria DNA on the ISS suggests

their possible transfer from the stratosphere into the ionosphere with

the ascending branch of the global atmospheric electrical circuit. Alternatively, the wild land and marine bacteria as well as the ISS bacteria may all have an ultimate space origin."

In October 2018, Harvard astronomers presented an analytical model that suggests matter—and potentially dormant spores—can be exchanged across the vast distances between galaxies, a process termed 'galactic panspermia', and not be restricted to the limited scale of solar systems. The detection of an extra-solar object named ʻOumuamua crossing the inner Solar System in a

hyperbolic orbit confirms the existence of a continuing material link with exoplanetary systems.

In November 2019, scientists reported detecting, for the first time, sugar molecules, including ribose, in meteorites, suggesting that chemical processes on asteroids can produce some fundamentally essential bio-ingredients important to life, and supporting the notion of an RNA world prior to a DNA-based origin of life on Earth, and possibly, as well, the notion of panspermia.

Proposed mechanisms

Panspermia can be said to be either interstellar (between star systems) or interplanetary (between planets in the same star system); its transport mechanisms may include comets, radiation pressure and lithopanspermia (microorganisms embedded in rocks). Interplanetary transfer of nonliving material is well documented, as evidenced by meteorites of Martian origin found on Earth. Space probes

may also be a viable transport mechanism for interplanetary

cross-pollination in the Solar System or even beyond. However, space

agencies have implemented planetary protection procedures to reduce the risk of planetary contamination, although, as recently discovered, some microorganisms, such as Tersicoccus phoenicis, may be resistant to procedures used in spacecraft assembly clean room facilities.

In 2012, mathematician Edward Belbruno and astronomers Amaya Moro-Martín and Renu Malhotra proposed that gravitational low-energy transfer of rocks among the young planets of stars in their birth cluster is commonplace, and not rare in the general galactic stellar population. Deliberate directed panspermia from space to seed Earth or sent from Earth to seed other planetary systems have also been proposed. One twist to the hypothesis by engineer Thomas Dehel (2006), proposes that plasmoid magnetic fields ejected from the magnetosphere

may move the few spores lifted from the Earth's atmosphere with

sufficient speed to cross interstellar space to other systems before the

spores can be destroyed.

Radiopanspermia

In 1903, Svante Arrhenius published in his article The Distribution of Life in Space, the hypothesis now called radiopanspermia, that microscopic forms of life can be propagated in space, driven by the radiation pressure from stars.

Arrhenius argued that particles at a critical size below 1.5 μm would

be propagated at high speed by radiation pressure of the Sun. However,

because its effectiveness decreases with increasing size of the

particle, this mechanism holds for very tiny particles only, such as

single bacterial spores.

The main criticism of radiopanspermia hypothesis came from Iosif Shklovsky and Carl Sagan, who pointed out the proofs of the lethal action of space radiations (UV and X-rays) in the cosmos.

Regardless of the evidence, Wallis and Wickramasinghe argued in 2004

that the transport of individual bacteria or clumps of bacteria, is

overwhelmingly more important than lithopanspermia in terms of numbers

of microbes transferred, even accounting for the death rate of

unprotected bacteria in transit.

Then, data gathered by the orbital experiments ERA, BIOPAN, EXOSTACK and EXPOSE, determined that isolated spores, including those of B. subtilis, were killed if exposed to the full space environment for merely a few seconds, but if shielded against solar UV,

the spores were capable of surviving in space for up to six years while

embedded in clay or meteorite powder (artificial meteorites).

Minimal protection is required to shelter a spore against UV

radiation: Exposure of unprotected DNA to solar UV and cosmic ionizing

radiation break it up into its constituent bases.

Also, exposing DNA to the ultrahigh vacuum of space alone is sufficient

to cause DNA damage, so the transport of unprotected DNA or RNA during

interplanetary flights powered solely by light pressure is extremely

unlikely.

The feasibility of other means of transport for the more massive

shielded spores into the outer Solar System – for example, through

gravitational capture by comets – is at this time unknown.

Based on experimental data on radiation effects and DNA

stability, it has been concluded that for such long travel times,

boulder-sized rocks which are greater than or equal to 1 meter in

diameter are required to effectively shield resistant microorganisms,

such as bacterial spores against galactic cosmic radiation.

These results clearly negate the radiopanspermia hypothesis, which

requires single spores accelerated by the radiation pressure of the Sun,

requiring many years to travel between the planets, and support the

likelihood of interplanetary transfer of microorganisms within asteroids or comets, the so-called lithopanspermia hypothesis.

Lithopanspermia

Lithopanspermia,

the transfer of organisms in rocks from one planet to another either

through interplanetary or interstellar space, remains speculative.

Although there is no evidence that lithopanspermia has occurred in the

Solar System, the various stages have become amenable to experimental

testing.

- Planetary ejection — For lithopanspermia to occur, researchers have suggested that microorganisms must survive ejection from a planetary surface which involves extreme forces of acceleration and shock with associated temperature excursions. Hypothetical values of shock pressures experienced by ejected rocks are obtained with Martian meteorites, which suggest the shock pressures of approximately 5 to 55 GPa, acceleration of 3 Mm/s2 and jerk of 6 Gm/s3 and post-shock temperature increases of about 1 K to 1000 K. To determine the effect of acceleration during ejection on microorganisms, rifle and ultracentrifuge methods were successfully used under simulated outer space conditions.

- Survival in transit — The survival of microorganisms has been studied extensively using both simulated facilities and in low Earth orbit. A large number of microorganisms have been selected for exposure experiments. It is possible to separate these microorganisms into two groups, the human-borne, and the extremophiles. Studying the human-borne microorganisms is significant for human welfare and future manned missions; whilst the extremophiles are vital for studying the physiological requirements of survival in space.

- Atmospheric entry — An important aspect of the lithopanspermia hypothesis to test is that microbes situated on or within rocks could survive hypervelocity entry from space through Earth's atmosphere (Cockell, 2008). As with planetary ejection, this is experimentally tractable, with sounding rockets and orbital vehicles being used for microbiological experiments. B. subtilis spores inoculated onto granite domes were subjected to hypervelocity atmospheric transit (twice) by launch to a ∼120 km altitude on an Orion two-stage rocket. The spores were shown to have survived on the sides of the rock, but they did not survive on the forward-facing surface that was subjected to a maximum temperature of 145 °C. The exogenous arrival of photosynthetic microorganisms could have quite profound consequences for the course of biological evolution on the inoculated planet. As photosynthetic organisms must be close to the surface of a rock to obtain sufficient light energy, atmospheric transit might act as a filter against them by ablating the surface layers of the rock. Although cyanobacteria have been shown to survive the desiccating, freezing conditions of space in orbital experiments, this would be of no benefit as the STONE experiment showed that they cannot survive atmospheric entry. Thus, non-photosynthetic organisms deep within rocks have a chance to survive the exit and entry process. Research presented at the European Planetary Science Congress in 2015 suggests that ejection, entry and impact is survivable for some simple organisms.

Accidental panspermia

Thomas Gold, a professor of astronomy, suggested in 1960 the hypothesis of "Cosmic Garbage", that life on Earth might have originated accidentally from a pile of waste products dumped on Earth long ago by extraterrestrial beings.

Directed panspermia

Directed panspermia concerns the deliberate transport of

microorganisms in space, sent to Earth to start life here, or sent from

Earth to seed new planetary systems with life by introduced species of microorganisms on lifeless planets. The Nobel prize winner Francis Crick, along with Leslie Orgel proposed that life may have been purposely spread by an advanced extraterrestrial civilization, but considering an early "RNA world" Crick noted later that life may have originated on Earth.

It has been suggested that 'directed' panspermia was proposed in order

to counteract various objections, including the argument that microbes

would be inactivated by the space environment and cosmic radiation before they could make a chance encounter with Earth.

Conversely, active directed panspermia has been proposed to secure and expand life in space.

This may be motivated by biotic ethics that values, and seeks to

propagate, the basic patterns of our organic gene/protein life-form.

The panbiotic program would seed new planetary systems nearby, and

clusters of new stars in interstellar clouds. These young targets, where

local life would not have formed yet, avoid any interference with local

life.

For example, microbial payloads launched by solar sails at speeds up to 0.0001 c

(30,000 m/s) would reach targets at 10 to 100 light-years in 0.1

million to 1 million years. Fleets of microbial capsules can be aimed at

clusters of new stars in star-forming clouds, where they may land on

planets or be captured by asteroids and comets and later delivered to

planets. Payloads may contain extremophiles for diverse environments and cyanobacteria similar to early microorganisms. Hardy multicellular organisms (rotifer cysts) may be included to induce higher evolution.

The probability of hitting the target zone can be calculated from where A(target) is the cross-section of the target area, dy is the positional uncertainty at arrival; a – constant (depending on units), r(target) is the radius of the target area; v the velocity of the probe; (tp) the targeting precision (arcsec/yr); and d the distance to the target, guided by high-resolution astrometry of 1×10−5

arcsec/yr (all units in SIU). These calculations show that relatively

near target stars(Alpha PsA, Beta Pictoris) can be seeded by milligrams

of launched microbes; while seeding the Rho Ophiochus star-forming cloud

requires hundreds of kilograms of dispersed capsules.

Directed panspermia to secure and expand life in space is becoming possible because of developments in solar sails, precise astrometry, extrasolar planets, extremophiles and microbial genetic engineering. After determining the composition of chosen meteorites, astroecologists

performed laboratory experiments that suggest that many colonizing

microorganisms and some plants could obtain many of their chemical

nutrients from asteroid and cometary materials. However, the scientists noted that phosphate (PO4) and nitrate (NO3–N) critically limit nutrition to many terrestrial lifeforms.

With such materials, and energy from long-lived stars, microscopic life

planted by directed panspermia could find an immense future in the

galaxy.

A number of publications since 1979 have proposed the idea that

directed panspermia could be demonstrated to be the origin of all life

on Earth if a distinctive 'signature' message were found, deliberately

implanted into either the genome or the genetic code of the first microorganisms by our hypothetical progenitor.

In 2013 a team of physicists claimed that they had found mathematical and semiotic patterns in the genetic code which they think is evidence for such a signature. This claim has been challenged by biologist PZ Myers who said, writing in Pharyngula:

Unfortunately, what they’ve so honestly described is good old honest garbage ... Their methods failed to recognize a well-known functional association in the genetic code; they did not rule out the operation of natural law before rushing to falsely infer design ... We certainly don’t need to invoke panspermia. Nothing in the genetic code requires design. and the authors haven’t demonstrated otherwise.

In a later peer-reviewed article, the authors

address the operation of natural law in an extensive statistical test,

and draw the same conclusion as in the previous article. In special sections they also discuss methodological concerns raised by PZ Myers and some others.

Pseudo-panspermia

Pseudo-panspermia (sometimes called soft panspermia, molecular

panspermia or quasi-panspermia) proposes that the organic molecules used

for life originated in space and were incorporated in the solar nebula,

from which the planets condensed and were further —and continuously—

distributed to planetary surfaces where life then emerged (abiogenesis).

From the early 1970s it was becoming evident that interstellar dust

consisted of a large component of organic molecules. The first

suggestion came from Chandra Wickramasinghe, who proposed a polymeric composition based on the molecule formaldehyde (CH2O).

Interstellar molecules are formed by chemical reactions within

very sparse interstellar or circumstellar clouds of dust and gas.

Usually this occurs when a molecule becomes ionized, often as the result of an interaction with cosmic rays.

This positively charged molecule then draws in a nearby reactant by

electrostatic attraction of the neutral molecule's electrons. Molecules

can also be generated by reactions between neutral atoms and molecules,

although this process is generally slower. The dust plays a critical role of shielding the molecules from the ionizing effect of ultraviolet radiation emitted by stars.

A 2008 analysis of 12C/13C isotopic ratios of organic compounds found in the Murchison meteorite

indicates a non-terrestrial origin for these molecules rather than

terrestrial contamination. Biologically relevant molecules identified so

far include uracil, an RNA nucleobase, and xanthine.

These results demonstrate that many organic compounds which are

components of life on Earth were already present in the early Solar

System and may have played a key role in life's origin.

In August 2009, NASA scientists identified one of the fundamental chemical building-blocks of life (the amino acid glycine) in a comet for the first time.

In August 2011, a report, based on NASA studies with meteorites found on Earth, was published suggesting building blocks of DNA (adenine, guanine and related organic molecules) may have been formed extraterrestrially in outer space. In October 2011, scientists reported that cosmic dust contains complex organic matter ("amorphous organic solids with a mixed aromatic-aliphatic structure") that could be created naturally, and rapidly, by stars.

One of the scientists suggested that these complex organic compounds

may have been related to the development of life on Earth and said that,

"If this is the case, life on Earth may have had an easier time getting

started as these organics can serve as basic ingredients for life."

In August 2012, and in a world first, astronomers at Copenhagen University reported the detection of a specific sugar molecule, glycolaldehyde, in a distant star system. The molecule was found around the protostellar binary IRAS 16293-2422, which is located 400 light years from Earth. Glycolaldehyde is needed to form ribonucleic acid, or RNA, which is similar in function to DNA.

This finding suggests that complex organic molecules may form in

stellar systems prior to the formation of planets, eventually arriving

on young planets early in their formation.

In September 2012, NASA scientists reported that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), subjected to interstellar medium (ISM) conditions, are transformed, through hydrogenation, oxygenation and hydroxylation, to more complex organics – "a step along the path toward amino acids and nucleotides, the raw materials of proteins and DNA, respectively". Further, as a result of these transformations, the PAHs lose their spectroscopic signature which could be one of the reasons "for the lack of PAH detection in interstellar ice grains, particularly the outer regions of cold, dense clouds or the upper molecular layers of protoplanetary disks."

In 2013, the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA Project) confirmed that researchers have discovered an important pair of prebiotic molecules in the icy particles in interstellar space

(ISM). The chemicals, found in a giant cloud of gas about 25,000

light-years from Earth in ISM, may be a precursor to a key component of

DNA and the other may have a role in the formation of an important amino acid. Researchers found a molecule called cyanomethanimine, which produces adenine, one of the four nucleobases that form the "rungs" in the ladder-like structure of DNA.

The other molecule, called ethanamine, is thought to play a role in forming alanine,

one of the twenty amino acids in the genetic code. Previously,

scientists thought such processes took place in the very tenuous gas

between the stars. The new discoveries, however, suggest that the

chemical formation sequences for these molecules occurred not in gas,

but on the surfaces of ice grains in interstellar space.

NASA ALMA scientist Anthony Remijan stated that finding these molecules

in an interstellar gas cloud means that important building blocks for

DNA and amino acids can 'seed' newly formed planets with the chemical

precursors for life.

In March 2013, a simulation experiment indicate that dipeptides (pairs of amino acids) that can be building blocks of proteins, can be created in interstellar dust.

In February 2014, NASA announced a greatly upgraded database for tracking polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the universe. According to scientists, more than 20% of the carbon in the universe may be associated with PAHs, possible starting materials for the formation of life. PAHs seem to have been formed shortly after the Big Bang, are widespread throughout the universe, and are associated with new stars and exoplanets.

In March 2015, NASA scientists reported that, for the first time, complex DNA and RNA organic compounds of life, including uracil, cytosine and thymine, have been formed in the laboratory under outer space conditions, using starting chemicals, such as pyrimidine, found in meteorites. Pyrimidine, like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), the most carbon-rich chemical found in the Universe, may have been formed in red giants or in interstellar dust and gas clouds, according to the scientists.

In May 2016, the Rosetta Mission team reported the presence of glycine, methylamine and ethylamine in the coma of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

This, plus the detection of phosphorus, is consistent with the

hypothesis that comets played a crucial role in the emergence of life on

Earth.

In 2019, the detection of extraterrestrial sugars in meteorites

implied the possibility that extraterrestrial sugars may have

contributed to forming functional biopolymers like RNA.

Extraterrestrial life

The chemistry of life may have begun shortly after the Big Bang, 13.8 billion years ago, during a habitable epoch when the Universe was only 10–17 million years old. According to the panspermia hypothesis, microscopic life—distributed by meteoroids, asteroids and other small Solar System bodies—may exist throughout the universe. Nonetheless, Earth is the only place in the universe known by humans to harbor life. The sheer number of planets in the Milky Way galaxy, however, may make it probable that life has arisen somewhere else in the galaxy and the universe. It is generally agreed that the conditions required for the evolution

of intelligent life as we know it are probably exceedingly rare in the

universe, while simultaneously noting that simple single-celled microorganisms may be more likely.

The extrasolar planet results from the Kepler mission estimate 100–400 billion exoplanets, with over 3,500 as candidates or confirmed exoplanets. On 4 November 2013, astronomers reported, based on Kepler space mission data, that there could be as many as 40 billion Earth-sized planets orbiting in the habitable zones of sun-like stars and red dwarf stars within the Milky Way Galaxy. 11 billion of these estimated planets may be orbiting sun-like stars. The nearest such planet may be 12 light-years away, according to the scientists.

It is estimated that space travel over cosmic distances would

take an incredibly long time to an outside observer, and with vast

amounts of energy required. However, some scientists hypothesize that faster-than-light interstellar space travel might be feasible. This has been explored by NASA scientists since at least 1995.

Hypotheses on extraterrestrial sources of illnesses

Hoyle

and Wickramasinghe have speculated that several outbreaks of illnesses

on Earth are of extraterrestrial origins, including the 1918 flu pandemic, and certain outbreaks of polio and mad cow disease. For the 1918 flu pandemic they hypothesized that cometary

dust brought the virus to Earth simultaneously at multiple locations—a

view almost universally dismissed by experts on this pandemic. Hoyle

also speculated that HIV came from outer space.

After Hoyle's death, The Lancet published a letter to the editor from Wickramasinghe and two of his colleagues, in which they hypothesized that the virus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) could be extraterrestrial in origin and not originated from chickens. The Lancet

subsequently published three responses to this letter, showing that the

hypothesis was not evidence-based, and casting doubts on the quality of

the experiments referenced by Wickramasinghe in his letter.

A 2008 encyclopedia notes that "Like other claims linking terrestrial

disease to extraterrestrial pathogens, this proposal was rejected by the

greater research community."

In April 2016, Jiangwen Qu of the Department of Infectious

Disease Control in China presented a statistical study suggesting that

"extremes of sunspot activity to within plus or minus 1 year may

precipitate influenza pandemics." He discussed possible mechanisms of

epidemic initiation and early spread, including speculation on primary

causation by externally derived viral variants from space via cometary

dust.

Case studies

- A meteorite originating from Mars known as ALH84001 was shown in 1996 to contain microscopic structures resembling small terrestrial nanobacteria. When the discovery was announced, many immediately conjectured that these were fossils and were the first evidence of extraterrestrial life — making headlines around the world. Public interest soon started to dwindle as most experts started to agree that these structures were not indicative of life, but could instead be formed abiotically from organic molecules. However, in November 2009, a team of scientists at Johnson Space Center, including David McKay, reasserted that there was "strong evidence that life may have existed on ancient Mars", after having reexamined the meteorite and finding magnetite crystals.

- On May 11, 2001, two researchers from the University of Naples claimed to have found viable extraterrestrial bacteria inside a meteorite. Geologist Bruno D'Argenio and molecular biologist Giuseppe Geraci claim the bacteria were wedged inside the crystal structure of minerals, but were resurrected when a sample of the rock was placed in a culture medium.

- An Indian and British team of researchers led by Chandra Wickramasinghe reported on 2001 that air samples over Hyderabad, India, gathered from the stratosphere by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) on January 21, 2001, contained clumps of living cells. Wickramasinghe calls this "unambiguous evidence for the presence of clumps of living cells in air samples from as high as 41 km, above which no air from lower down would normally be transported". Two bacterial and one fungal species were later independently isolated from these filters which were identified as Bacillus simplex, Staphylococcus pasteuri and Engyodontium album respectively. Pushkar Ganesh Vaidya from the Indian Astrobiology Research Centre reported in 2009 that "the three microorganisms captured during the balloon experiment do not exhibit any distinct adaptations expected to be seen in microorganisms occupying a cometary niche".

- In 2005 an improved experiment was conducted by ISRO. On April 20, 2005, air samples were collected from the upper atmosphere at altitudes ranging from 20 km to more than 40 km. The samples were tested at two labs in India. The labs found 12 bacterial and 6 different fungal species in these samples. The fungi were Penicillium decumbens, Cladosporium cladosporioides, Alternaria sp. and Tilletiopsis albescens. Out of the 12 bacterial samples, three were identified as new species and named Janibacter hoylei (after Fred Hoyle), Bacillus isronensis (named after ISRO) and Bacillus aryabhattai (named after the ancient Indian mathematician, Aryabhata). These three new species showed that they were more resistant to UV radiation than similar bacteria.

- Some other researchers have retrieved bacteria from the stratosphere since the 1970s. Atmospheric sampling by NASA in 2010 before and after hurricanes, collected 314 different types of bacteria; the study suggests that large-scale convection during tropical storms and hurricanes can then carry this material from the surface higher up into the atmosphere.

- Another proposed mechanism of spores in the stratosphere is lifting by weather and Earth magnetism up to the ionosphere into low Earth orbit, where Russian astronauts retrieved DNA from a known sterile exterior surface of the International Space Station. The Russian scientists then also speculated the possibility "that common terrestrial bacteria are constantly being resupplied from space."

- In 2013, Dale Warren Griffin, a microbiologist working at the United States Geological Survey noted that viruses are the most numerous entities on Earth. Griffin speculates that viruses evolved in comets and on other planets and moons may be pathogenic to humans, so he proposed to also look for viruses on moons and planets of the Solar System.

Hoaxes

A separate fragment of the Orgueil

meteorite (kept in a sealed glass jar since its discovery) was found in

1965 to have a seed capsule embedded in it, whilst the original glassy

layer on the outside remained undisturbed. Despite great initial

excitement, the seed was found to be that of a European Juncaceae or Rush plant that had been glued into the fragment and camouflaged using coal dust.

The outer "fusion layer" was in fact glue. Whilst the perpetrator of

this hoax is unknown, it is thought that they sought to influence the

19th century debate on spontaneous generation — rather than panspermia — by demonstrating the transformation of inorganic to biological matter.

Extremophiles

Hydrothermal vents are able to support extremophile bacteria on Earth and may also support life in other parts of the cosmos.

Until the 1970s, life was thought to depend on its access to sunlight.

Even life in the ocean depths, where sunlight cannot reach, was

believed to obtain its nourishment either from consuming organic

detritus rained down from the surface waters or from eating animals that

did. However, in 1977, during an exploratory dive to the Galapagos Rift in the deep-sea exploration submersible Alvin, scientists discovered colonies of assorted creatures clustered around undersea volcanic features known as black smokers.

It was soon determined that the basis for this food chain is a form of bacterium that derives its energy from oxidation of reactive chemicals, such as hydrogen or hydrogen sulfide, that bubble up from the Earth's interior. This chemosynthesis

revolutionized the study of biology by revealing that terrestrial life

need not be Sun-dependent; it only requires water and an energy gradient

in order to exist.

It is now known that extremophiles,

microorganisms with extraordinary capability to thrive in the harshest

environments on Earth, can specialize to thrive in the deep-sea,

ice, boiling water, acid, the water core of nuclear reactors, salt

crystals, toxic waste and in a range of other extreme habitats that were

previously thought to be inhospitable for life. Living bacteria found in ice core samples retrieved from 3,700 metres (12,100 ft) deep at Lake Vostok in Antarctica,

have provided data for extrapolations to the likelihood of

microorganisms surviving frozen in extraterrestrial habitats or during

interplanetary transport. Also, bacteria have been discovered living within warm rock deep in the Earth's crust.

In order to test some of these organisms' potential resilience in outer space, plant seeds and spores of bacteria, fungi and ferns have been exposed to the harsh space environment. Spores are produced as part of the normal life cycle of many plants, algae, fungi and some protozoans, and some bacteria produce endospores or cysts during times of stress. These structures may be highly resilient to ultraviolet and gamma radiation, desiccation, lysozyme, temperature, starvation and chemical disinfectants, while metabolically inactive. Spores germinate when favourable conditions are restored after exposure to conditions fatal to the parent organism.

Although computer models suggest that a captured meteoroid would

typically take some tens of millions of years before collision with a

planet, there are documented viable Earthly bacterial spores that are 40 million years old that are very resistant to radiation, and others able to resume life after being dormant for 25 million years, suggesting that lithopanspermia life-transfers are possible via meteorites exceeding 1 m in size.

The discovery of deep-sea ecosystems, along with advancements in the fields of astrobiology, observational astronomy

and discovery of large varieties of extremophiles, opened up a new

avenue in astrobiology by massively expanding the number of possible extraterrestrial habitats and possible transport of hardy microbial life through vast distances.

Research in outer space

The question of whether certain microorganisms

can survive in the harsh environment of outer space has intrigued

biologists since the beginning of spaceflight, and opportunities were

provided to expose samples to space. The first American tests were made

in 1966, during the Gemini IX and XII missions, when samples of bacteriophage T1 and spores of Penicillium roqueforti were exposed to outer space for 16.8 h and 6.5 h, respectively. Other basic life sciences research in low Earth orbit started in 1966 with the Soviet biosatellite program Bion and the U.S. Biosatellite program. Thus, the plausibility of panspermia can be evaluated by examining life forms on Earth for their capacity to survive in space. The following experiments carried on low Earth orbit specifically tested some aspects of panspermia or lithopanspermia:

ERA

EURECA facility deployment in 1992

The Exobiology Radiation Assembly (ERA) was a 1992 experiment on board the European Retrievable Carrier (EURECA) on the biological effects of space radiation. EURECA was an unmanned 4.5 tonne satellite with a payload of 15 experiments. It was an astrobiology mission developed by the European Space Agency (ESA). Spores of different strains of Bacillus subtilis and the Escherichia coli plasmid pUC19

were exposed to selected conditions of space (space vacuum and/or

defined wavebands and intensities of solar ultraviolet radiation). After

the approximately 11-month mission, their responses were studied in

terms of survival, mutagenesis in the his (B. subtilis) or lac locus (pUC19), induction of DNA strand breaks, efficiency of DNA repair

systems, and the role of external protective agents. The data were

compared with those of a simultaneously running ground control

experiment:

- The survival of spores treated with the vacuum of space, however shielded against solar radiation, is substantially increased, if they are exposed in multilayers and/or in the presence of glucose as protective.

- All spores in "artificial meteorites", i.e. embedded in clays or simulated Martian soil, are killed.

- Vacuum treatment leads to an increase of mutation frequency in spores, but not in plasmid DNA.

- Extraterrestrial solar ultraviolet radiation is mutagenic, induces strand breaks in the DNA and reduces survival substantially.

- Action spectroscopy confirms results of previous space experiments of a synergistic action of space vacuum and solar UV radiation with DNA being the critical target.

- The decrease in viability of the microorganisms could be correlated with the increase in DNA damage.

- The purple membranes, amino acids and urea were not measurably affected by the dehydrating condition of open space, if sheltered from solar radiation. Plasmid DNA, however, suffered a significant amount of strand breaks under these conditions.

BIOPAN

BIOPAN is a multi-user experimental facility installed on the external surface of the Russian Foton descent capsule.

Experiments developed for BIOPAN are designed to investigate the effect

of the space environment on biological material after exposure between

13 and 17 days. The experiments in BIOPAN are exposed to solar and cosmic radiation,

the space vacuum and weightlessness, or a selection thereof. Of the 6

missions flown so far on BIOPAN between 1992 and 2007, dozens of

experiments were conducted, and some analyzed the likelihood of

panspermia. Some bacteria, lichens (Xanthoria elegans, Rhizocarpon geographicum and their mycobiont cultures, the black Antarctic microfungi Cryomyces minteri and Cryomyces antarcticus), spores, and even one animal (tardigrades) were found to have survived the harsh outer space environment and cosmic radiation.

EXOSTACK

EXOSTACK on the Long Duration Exposure Facility satellite.

The German EXOSTACK experiment was deployed on 7 April 1984 on board the Long Duration Exposure Facility satellite. 30% of Bacillus subtilis spores

survived the nearly 6 years exposure when embedded in salt crystals,

whereas 80% survived in the presence of glucose, which stabilize the

structure of the cellular macromolecules, especially during

vacuum-induced dehydration.

If shielded against solar UV, spores of B. subtilis

were capable of surviving in space for up to 6 years, especially if

embedded in clay or meteorite powder (artificial meteorites). The data

support the likelihood of interplanetary transfer of microorganisms

within meteorites, the so-called lithopanspermia hypothesis.

EXPOSE

Location of the astrobiology EXPOSE-E and EXPOSE-R facilities on the International Space Station

EXPOSE is a multi-user facility mounted outside the International Space Station dedicated to astrobiology experiments. There have been three EXPOSE experiments flown between 2008 and 2015: EXPOSE-E, EXPOSE-R and EXPOSE-R2.

Results from the orbital missions, especially the experiments SEEDS and LiFE, concluded that after an 18-month exposure, some seeds and lichens (Stichococcus sp. and Acarospora sp., a lichenized fungal genus) may be capable to survive interplanetary travel if sheltered inside comets or rocks from cosmic radiation and UV radiation. The LIFE, SPORES, and SEEDS parts of the experiments provided information about the likelihood of lithopanspermia. These studies will provide experimental data to the lithopanspermia hypothesis, and they will provide basic data to planetary protection issues.

Tanpopo

Dust collector with aerogel blocks

The Tanpopo mission is an orbital astrobiology experiment by Japan that is currently investigating the possible interplanetary transfer of life, organic compounds,

and possible terrestrial particles in low Earth orbit. The Tanpopo

experiment took place at the Exposed Facility located on the exterior of

Kibo module of the International Space Station. The mission collected cosmic dusts and other particles for three years by using an ultra-low density silica gel called aerogel.

The purpose is to assess the panspermia hypothesis and the possibility

of natural interplanetary transport of life and its precursors. Some of these aerogels were replaced every one or two years through 2018. Sample collection began in May 2015, and the first samples were returned to Earth in mid-2016. Analyses are ongoing.

Criticism

Panspermia is often criticized because it does not answer the question of the origin of life

but merely places it on another celestial body. It was also criticized

because it was thought it could not be tested experimentally.

Wallis and Wickramasinghe argued in 2004 that the transport of

individual bacteria or clumps of bacteria, is overwhelmingly more

important than lithopanspermia in terms of numbers of microbes

transferred, even accounting for the death rate of unprotected bacteria

in transit. Then it was found that isolated spores of B. subtilis

were killed by several orders of magnitude if exposed to the full space

environment for a mere few seconds. Though these results may seem to

negate the original panspermia hypothesis, the type of microorganism

making the long journey is inherently unknown and also its features

unknown. It could then be impossible to dismiss the hypothesis based on

the hardiness of a few earth-evolved microorganism. Also, if shielded

against solar UV, spores of Bacillus subtilis

were capable of surviving in space for up to 6 years, especially if

embedded in clay or meteorite powder (artificial meteorites). The data

support the likelihood of interplanetary transfer of microorganisms

within meteorites, the so-called lithopanspermia hypothesis.