https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Correspondence_principle

In physics, the correspondence principle states that the behavior of systems described by the theory of quantum mechanics (or by the old quantum theory) reproduces classical physics in the limit of large quantum numbers. In other words, it says that for large orbits and for large energies, quantum calculations must agree with classical calculations.

The principle was formulated by Niels Bohr in 1920, though he had previously made use of it as early as 1913 in developing his model of the atom.

The term codifies the idea that a new theory should reproduce under some conditions the results of older well-established theories in those domains where the old theories work. This concept is somewhat different from the requirement of a formal limit under which the new theory reduces to the older, thanks to the existence of a deformation parameter.

Classical quantities appear in quantum mechanics in the form of expected values of observables, and as such the Ehrenfest theorem (which predicts the time evolution of the expected values) lends support to the correspondence principle.

In physics, the correspondence principle states that the behavior of systems described by the theory of quantum mechanics (or by the old quantum theory) reproduces classical physics in the limit of large quantum numbers. In other words, it says that for large orbits and for large energies, quantum calculations must agree with classical calculations.

The principle was formulated by Niels Bohr in 1920, though he had previously made use of it as early as 1913 in developing his model of the atom.

The term codifies the idea that a new theory should reproduce under some conditions the results of older well-established theories in those domains where the old theories work. This concept is somewhat different from the requirement of a formal limit under which the new theory reduces to the older, thanks to the existence of a deformation parameter.

Classical quantities appear in quantum mechanics in the form of expected values of observables, and as such the Ehrenfest theorem (which predicts the time evolution of the expected values) lends support to the correspondence principle.

Quantum mechanics

The rules of quantum mechanics are highly successful in describing microscopic objects, atoms and elementary particles. But macroscopic systems, like springs and capacitors, are accurately described by classical theories like classical mechanics and classical electrodynamics.

If quantum mechanics were to be applicable to macroscopic objects,

there must be some limit in which quantum mechanics reduces to classical

mechanics. Bohr's correspondence principle demands that classical

physics and quantum physics give the same answer when the systems become

large. A. Sommerfeld (1921) referred to the principle as "Bohrs Zauberstab" (Bohr's magic wand).

The conditions under which quantum and classical physics agree are referred to as the correspondence limit, or the classical limit. Bohr provided a rough prescription for the correspondence limit: it occurs when the quantum numbers describing the system are large.

A more elaborated analysis of quantum-classical correspondence (QCC) in

wavepacket spreading leads to the distinction between robust

"restricted QCC" and fragile "detailed QCC".

"Restricted QCC" refers to the first two moments of the probability

distribution and is true even when the wave packets diffract, while

"detailed QCC" requires smooth potentials which vary over scales much

larger than the wavelength, which is what Bohr considered.

The post-1925 new quantum theory came in two different formulations. In matrix mechanics, the correspondence principle was built in and was used to construct the theory. In the Schrödinger approach

classical behavior is not clear because the waves spread out as they

move. Once the Schrödinger equation was given a probabilistic

interpretation, Ehrenfest showed that Newton's laws hold on average: the quantum statistical expectation value of the position and momentum obey Newton's laws.

The correspondence principle is one of the tools available to physicists for selecting quantum theories corresponding to reality. The principles of quantum mechanics are broad: states of a physical system form a complex vector space and physical observables are identified with Hermitian operators that act on this Hilbert space. The correspondence principle limits the choices to those that reproduce classical mechanics in the correspondence limit.

Because quantum mechanics only reproduces classical mechanics in a

statistical interpretation, and because the statistical interpretation

only gives the probabilities of different classical outcomes, Bohr

has argued that quantum physics does not reduce to classical mechanics

similarly as classical mechanics emerges as an approximation of special relativity at small velocities.

He argued that classical physics exists independently of quantum theory

and cannot be derived from it. His position is that it is inappropriate

to understand the experiences of observers using purely quantum

mechanical notions such as wavefunctions because the different states of

experience of an observer are defined classically, and do not have a

quantum mechanical analog. The relative state interpretation

of quantum mechanics is an attempt to understand the experience of

observers using only quantum mechanical notions. Niels Bohr was an early

opponent of such interpretations.

Many of these conceptual problems, however, resolve in the phase-space formulation of quantum mechanics, where the same variables with the same interpretation are utilized to describe both quantum and classical mechanics.

Other scientific theories

The term "correspondence principle" is used in a more general sense to mean the reduction of a new scientific theory

to an earlier scientific theory in appropriate circumstances. This

requires that the new theory explain all the phenomena under

circumstances for which the preceding theory was known to be valid, the

"correspondence limit".

For example,

- Einstein's special relativity satisfies the correspondence principle, because it reduces to classical mechanics in the limit of velocities small compared to the speed of light (example below);

- General relativity reduces to Newtonian gravity in the limit of weak gravitational fields;

- Laplace's theory of celestial mechanics reduces to Kepler's when interplanetary interactions are ignored;

- Statistical mechanics reproduces thermodynamics when the number of particles is large;

- In biology, chromosome inheritance theory reproduces Mendel's laws of inheritance, in the domain that the inherited factors are protein coding genes.

In order for there to be a correspondence, the earlier theory has to have a domain of validity—it must work under some conditions. Not all theories have a domain of validity. For example, there is no limit where Newton's mechanics reduces to Aristotle's mechanics

because Aristotle's mechanics, although academically dominant for 18

centuries, does not have any domain of validity (on the other hand, it

can sensibly be said that the falling of objects through the air ("natural motion") constitutes a domain of validity for a part of Aristotle's mechanics).

Examples

Bohr model

If an electron in an atom is moving on an orbit with period T,

classically the electromagnetic radiation will repeat itself every

orbital period. If the coupling to the electromagnetic field is weak, so

that the orbit doesn't decay very much in one cycle, the radiation will

be emitted in a pattern which repeats every period, so that the Fourier

transform will have frequencies which are only multiples of 1/T. This is the classical radiation law: the frequencies emitted are integer multiples of 1/T.

In quantum mechanics, this emission must be in quanta of light, of frequencies consisting of integer multiples of 1/T,

so that classical mechanics is an approximate description at large

quantum numbers. This means that the energy level corresponding to a

classical orbit of period 1/T must have nearby energy levels which differ in energy by h/T, and they should be equally spaced near that level,

Bohr worried whether the energy spacing 1/T should be best calculated with the period of the energy state , or , or some average—in hindsight, this model is only the leading semiclassical approximation.

Bohr considered circular orbits. Classically, these orbits must

decay to smaller circles when photons are emitted. The level spacing

between circular orbits can be calculated with the correspondence

formula. For a Hydrogen atom, the classical orbits have a period T determined by Kepler's third law to scale as r3/2. The energy scales as 1/r, so the level spacing formula amounts to

It is possible to determine the energy levels by recursively stepping down orbit by orbit, but there is a shortcut.

The angular momentum L of the circular orbit scales as √r. The energy in terms of the angular momentum is then

Assuming, with Bohr, that quantized values of L are equally spaced, the spacing between neighboring energies is

This is as desired for equally spaced angular momenta. If one kept track of the constants, the spacing would be ħ, so the angular momentum should be an integer multiple of ħ,

This is how Bohr arrived at his model. Since only the level spacing is determined heuristically by the correspondence principle, one could always add a small fixed offset to the quantum number— L could just as well have been (n+.338) ħ.

Bohr used his physical intuition to decide which quantities were

best to quantize. It is a testimony to his skill that he was able to get

so much from what is only the leading order approximation. A less heuristic treatment accounts for needed offsets in the ground state L2, cf. Wigner–Weyl transform.

One-dimensional potential

Bohr's

correspondence condition can be solved for the level energies in a

general one-dimensional potential. Define a quantity J(E) which is a function only of the energy, and has the property that

This is the analog of the angular momentum in the case of the

circular orbits. The orbits selected by the correspondence principle are

the ones that obey J = nh for n integer, since

This quantity J is canonically conjugate to a variable θ which, by the Hamilton equations of motion changes with time as the gradient of energy with J. Since this is equal to the inverse period at all times, the variable θ increases steadily from 0 to 1 over one period.

The angle variable comes back to itself after 1 unit of increase, so the geometry of phase space in J,θ coordinates is that of a half-cylinder, capped off at J = 0, which is the motionless orbit at the lowest value of the energy. These coordinates are just as canonical as x,p, but the orbits are now lines of constant J instead of nested ovoids in x-p space.

The area enclosed by an orbit is invariant under canonical transformations, so it is the same in x-p space as in J-θ. But in the J-θ coordinates, this area is the area of a cylinder of unit circumference between 0 and J, or just J. So J is equal to the area enclosed by the orbit in x-p coordinates too,

Multiperiodic motion: Bohr–Sommerfeld quantization

Bohr's

correspondence principle provided a way to find the semiclassical

quantization rule for a one degree of freedom system. It was an argument

for the old quantum condition mostly independent from the one developed

by Wien and Einstein, which focused on adiabatic invariance. But both pointed to the same quantity, the action.

Bohr was reluctant to generalize the rule to systems with many degrees of freedom. This step was taken by Sommerfeld, who proposed the general quantization rule for an integrable system,

Each action variable is a separate integer, a separate quantum number.

This condition reproduces the circular orbit condition for two dimensional motion: let r,θ be polar coordinates for a central potential. Then θ is already an angle variable, and the canonical momentum conjugate is L, the angular momentum. So the quantum condition for L reproduces Bohr's rule:

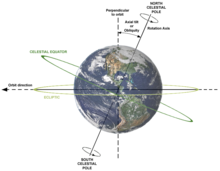

This allowed Sommerfeld to generalize Bohr's theory of circular

orbits to elliptical orbits, showing that the energy levels are the

same. He also found some general properties of quantum angular momentum

which seemed paradoxical at the time. One of these results was that the

z-component of the angular momentum, the classical inclination of an

orbit relative to the z-axis, could only take on discrete values, a

result which seemed to contradict rotational invariance. This was called

space quantization for a while, but this term fell out of favor with the new quantum mechanics since no quantization of space is involved.

In modern quantum mechanics, the principle of superposition makes

it clear that rotational invariance is not lost. It is possible to

rotate objects with discrete orientations to produce superpositions of

other discrete orientations, and this resolves the intuitive paradoxes

of the Sommerfeld model.

The quantum harmonic oscillator

Here is a demonstration

of how large quantum numbers can give rise to classical (continuous) behavior.

Consider the one-dimensional quantum harmonic oscillator. Quantum mechanics tells us that the total (kinetic and potential) energy of the oscillator, E, has a set of discrete values,

where ω is the angular frequency of the oscillator.

However, in a classical harmonic oscillator

such as a lead ball attached to the end of a spring, we do not perceive

any discreteness. Instead, the energy of such a macroscopic system

appears to vary over a continuum of values. We can verify that our idea

of macroscopic systems fall within the correspondence limit. The energy of the classical harmonic oscillator with amplitude A, is

Thus, the quantum number has the value

If we apply typical "human-scale" values m = 1kg, ω = 1 rad/s, and A = 1 m, then n ≈ 4.74×1033. This is a very large number, so the system is indeed in the correspondence limit.

It is simple to see why we perceive a continuum of energy in this limit. With ω = 1 rad/s, the difference between each energy level is ħω ≈ 1.05 × 10−34J, well below what we normally resolve for macroscopic systems. One then describes this system through an emergent classical limit.

Relativistic kinetic energy

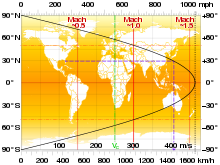

Here we show that the expression of kinetic energy from special relativity becomes arbitrarily close to the classical expression, for speeds that are much slower than the speed of light, v ≪ c.

Einstein's mass-energy equation

where the velocity, v is the velocity of the body relative to the observer, is the rest mass (the observed mass of the body at zero velocity relative to the observer), and c is the speed of light.

When the velocity v vanishes, the energy expressed above is not zero, and represents the rest energy,

When the body is in motion relative to the observer, the total energy exceeds the rest energy by an amount that is, by definition, the kinetic energy,

Using the approximation

-

-

- for

-

we get, when speeds are much slower than that of light, or v ≪ c,

which is the Newtonian expression for kinetic energy.