Mountaintop removal mining (MTR), also known as mountaintop mining (MTM), is a form of surface mining at the summit or summit ridge of a mountain. Coal seams are extracted from a mountain by removing the land, or overburden, above the seams. This process is considered to be safer compared to underground mining because the coal seams are accessed from above instead of underground. In the United States, this method of coal mining is conducted in the Appalachian Mountains in the eastern United States. Explosives are used to remove up to 400 vertical feet (120 m) of mountain to expose underlying coal seams. Excess rock and soil is dumped into nearby valleys, in what are called "holler fills" ("hollow fills") or "valley fills".

The practice of MTM has been controversial. While there are economic benefits to this practice, there are also concerns for environmental and human health costs.

Overview

Mountaintop removal mining (MTR), also known as mountaintop mining (MTM), is a form of surface mining that involves the topographical alteration and/or removal of a summit, hill, or ridge to access buried coal seams.

The MTR process involves the removal of coal seams by first fully removing the overburden lying atop them, exposing the seams from above. This method differs from more traditional underground mining, where typically a narrow shaft is dug which allows miners to collect seams using various underground methods, while leaving the vast majority of the overburden undisturbed. The overburden from MTR is either placed back on the ridge, attempting to reflect the approximate original contour of the mountain, and/or is moved into neighboring valleys.

Excess rock and soil containing mining byproducts are disposed into nearby valleys, in what are called "holler fills" or "valley fills".

MTR in the United States is most often associated with the extraction of coal in the Appalachian Mountains. Google Earth Engine and Landsat imagery report the extent of newly mined land from 1985 to 2015 to be 2,900km2. Considering surface mining sites prior to 1985, the cumulative total of mined land was calculated to be 5,900km2. Further studies calculated that 12m2 of mined land produced one metric ton of coal. Sites range from Ohio to Virginia. It occurs most commonly in West Virginia and Eastern Kentucky, the top two coal-producing states in Appalachia. At current rates, MTR in the U.S. will mine over 1.4 million acres (5,700 km²) by 2010, an amount of land area that exceeds that of the state of Delaware. More than 500 mountains in the US have been destroyed by this process, resulting in the burial of 3,200 km (2,000 mi) of streams.

Mountaintop removal has been practiced since the 1960s. Increased demand for coal in the United States, sparked by the 1973 and 1979 petroleum crises, created incentives for a more economical form of coal mining than the traditional underground mining methods involving hundreds of workers, triggering the first widespread use of MTR. Its prevalence expanded further in the 1990s to retrieve relatively low-sulfur coal, a cleaner-burning form, which became desirable as a result of amendments to the U.S. Clean Air Act that tightened emissions limits on high-sulfur coal processing.

Process

"Step 1. Layers of rock and dirt above the coal (called overburden) are removed."

"Step 2. The upper seams of coal are removed with spoils placed in an adjacent valley."

"Step 3. Draglines excavate lower layers of coal with spoils placed in spoil piles."

"Step 4. Regrading begins as coal excavation continues."

"Step 5. Once coal removal is completed, final regrading takes place and the area is revegetated."

Mining

Land is deforested prior to mining operations and the resultant lumber is either sold or burned. According to the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 (SMCRA), the topsoil is supposed to be removed and set aside for later reclamation. However, coal companies are often granted waivers and instead reclaim the mountain with "topsoil substitute". The waivers are granted if adequate amounts of topsoil are not naturally present on the rocky ridge top. Once the area is cleared, miners use explosives to blast away the overburden, the rock and subsoil, to expose coal seams beneath. The overburden is then moved by various mechanical means to areas of the ridge previously mined. These areas are the most economical area of storage as they are located close to the active pit of exposed coal. If the ridge topography is too steep to adequately handle the amount of spoil produced then additional storage is used in a nearby valley or hollow, creating what is known as a valley fill or hollow fill. Any streams in a valley are buried by the overburden.

A front-end loader or excavator then removes the coal, where it is transported to a processing plant. Once coal removal is completed, the mining operators back stack overburden from the next area to be mined into the now empty pit. After backstacking and grading of overburden has been completed, topsoil (or a topsoil substitute) is layered over the overburden layer. Next, grass seed is spread in a mixture of seed, fertilizer, and mulch made from recycled newspaper. Depending on surface land owner wishes the land will then be further reclaimed by adding trees if the pre-approved post-mining land use is forest land or wildlife habitat. If the land owner has requested other post-mining land uses the land can be reclaimed to be used as pasture land, economic development or other uses specified in SMCRA.

Because coal usually exists in multiple geologically stratified seams, miners can often repeat the blasting process to mine over a dozen seams on a single mountain, increasing the mine depth each time. This can result in a vertical descent of hundreds of extra feet into the earth.

Reclamation

Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act

Established in 1977, the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act set up a program “for the regulation of surface mining activities and the reclamation of coal-mined lands”. Although U.S. mountaintop removal sites by law must be reclaimed after mining is complete, reclamation has traditionally focused on stabilizing rock formations and controlling for erosion, and not on the reforestation of the affected area. However, the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 list "the restoration of land and water resources" as a priority.

Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative (ARRI)

Historically, reforested mining sites have been characterized by seedling mortality, slow growth and poor production. Challenges associated with returning forests to their pre-mining state enabled grassland conversion to become standard. The Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative (ARRI), established in 2004, works to promote the growth of hardwood trees on reclaimed mining sites. The ARRI operates utilizing the Forestry Reclamation Approach (FRA). In an effort to apply specific forest restoration practices, the FRA focuses on five main reclamation components: (1) establish suitable soil deeper than four feet to enhance root growth, (2) ensure non-compacted topsoil is present, (3) plan vegetative ground cover to support tree growth (4) include tree species that support local wildlife, as well as commercially desired products, (5) ensure that proper planting techniques are utilized. This group also facilitates restoration efforts by educating and training members of the coal industry on their role in promoting and adopting effective management practices.

Valley fill sites

Valley fill sites can be characterized by high sulfur concentrations from the weathering process of mountaintop sulfur-rich debris. Additionally, acid mine drainage (AMD) increases the concentration of sulfate, iron, aluminum and manganese in surrounding streams. Some of the most common treatments include plugging mine openings, altering the landscape to divert incoming water from at risk ecosystems, alkaline inputs, limestone channels and treatment ponds or wetlands.

Biotic stream remediation index

Current remediation methods may vary, but expensive treatment costs persist. The cost efficiency of treatments can be increased through the use of models that are able to accurately predict ecosystem responses to various inputs; thus enabling restoration groups to determine the overall most effective treatment combination. Biotic indicators present within stream ecosystems impacted by valley fill (VF) activity and AMD are valuable assets to increase the cost efficiency of restoration efforts. Mayflies (Order Ephemeroptera) are abundant in streams in the Appalachian Mountain region.They are highly sensitive to water quality, as their immature forms require unpolluted water. VF and AMD are the leading causes of water chemistry and habitat alterations in this region, the driving factors limiting mayfly populations. Thus, they can be utilized as an effective indicator species to quantify restoration progress through modeling efforts focused on mountaintop mining driven changes in adjacent ecosystems. Effectively developed biotic response models can improve and refine restoration efforts by establishing target indicator species population goals and by enabling the monitoring and assessment of water chemistry and habitat changes impacting particular species.

Economics

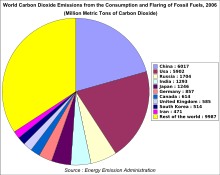

As of 2015, approximately one third of the electricity generated in the United States is produced by coal-fired power plants. MTR accounted for less than 5% of U.S. coal production as of 2001. In some regions, however, the percentage is higher, for example, MTR provided 30% of the coal mined in West Virginia in 2006.

Historically in the U.S. the prevalent method of coal acquisition was underground mining which is very labor-intensive. In MTR, through the use of explosives and large machinery, more than two and a half times as much coal can be extracted per worker per hour than in traditional underground mines, thus greatly reducing the need for workers. In Kentucky, for example, the number of workers has declined over 60% from 1979 to 2006 (from 47,190 to 17,959 workers). The industry overall lost approximately 10,000 jobs from 1990 to 1997, as MTR and other more mechanized underground mining methods became more widely used. The coal industry asserts that surface mining techniques, such as mountaintop removal, are safer for miners than sending miners underground.

Proponents argue that in certain geologic areas, MTR and similar forms of surface mining allow the only access to thin seams of coal that traditional underground mining would not be able to mine. MTR is sometimes the most cost-effective method of extracting coal.

Several studies of the impact of restrictions to mountaintop removal were authored in 2000 through 2005. Studies by Mark L. Burton, Michael J. Hicks and Cal Kent identified significant state-level tax losses attributable to lower levels of mining (notably the studies did not examine potential environmental costs, which the authors acknowledge may outweigh commercial benefits). Mountaintop removal sites are normally restored after the mining operation is complete, but "reclaimed soils characteristically have higher bulk density, lower organic content, low water-infiltration rates, and low nutrient content".

Reclamation projects designed in conjunction with community needs can aid local economic development. Previously mined land can be reclaimed as sustainable agricultural land and solar farms. These efforts can help to diversify and stimulate the local economy by providing jobs and other economic opportunities.

Legislation in the United States

In the United States, MTR is allowed by section 515(c)(1) of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977. Although most coal mining sites must be reclaimed to the land's pre-mining contour and use, regulatory agencies can issue waivers to allow MTR. In such cases, SMCRA dictates that reclamation must create "a level plateau or a gently rolling contour with no highwalls remaining".

Different organizations have tried to revise a stream buffer rule placed in 1977. The rule states that certain conditions must be met, or the mining operation must take place “within 100 feet of a stream”. The Obama Administration, in July 2015, wrote up a draft "Stream Protection Rule". This draft adds “more protections to downstream waters”, but it will also debilitate the current buffer requirements.

In February 2017, President Trump signed a bill that did away with the stream protection rule previously administered by the Obama Administration.

Permits must be obtained to deposit valley fill into streams. On four occasions, federal courts have ruled that the US Army Corps of Engineers violated the Clean Water Act by issuing such permits. Massey Energy Company is currently appealing a 2007 ruling, but has been allowed to continue mining in the meantime because "most of the substantial harm has already occurred," according to the judge.

The Bush administration appealed one of these rulings in 2001 because the Act had not explicitly defined "fill material" that could legally be placed in a waterway. The EPA and Army Corps of Engineers changed a rule to include mining debris in the definition of fill material, and the ruling was overturned.

On December 2, 2008, the Bush Administration made a rule change to remove the Stream Buffer Zone protection provision from SMCRA allowing coal companies to place mining waste rock and dirt directly into headwater waterways.

A federal judge has also ruled that using settling ponds to remove mining waste from streams violates the Clean Water Act. He also declared that the Army Corps of Engineers has no authority to issue permits allowing discharge of pollutants into such in-stream settling ponds, which are often built just below valley fills.

On January 15, 2008, the environmental advocacy group Center for Biological Diversity petitioned the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to end a policy that waives detailed federal Endangered Species Act reviews for new mining permits. Under current policy, as long as a given MTR mining operation complies with federal surface mining law, the agency presumes conclusively, despite the complexities of intra- and inter-species relationships, that the instance of MTR in question is not damaging to endangered species or their habitat. Since 1996, this policy has exempted many strip mines from being subject to permit-specific reviews of impact on individual endangered species. Because of the 1996 Biological Opinion by FWS making case-by-case formal reviews unnecessary, the Interior's Office of Surface Mining and state regulators require mining companies to hire a government-approved contractor to conduct their own surveys for any potential endangered species. The surveys require approval from state and federal biologists, who provide informal guidance on how to minimize mines' potential effects to species. While the agencies have the option to ask for formal endangered species consultations during that process, they do so very rarely.

On May 25, 2008, North Carolina State Representative Pricey Harrison introduced a bill to ban the use of mountaintop removal coal from coal-fired power plants within North Carolina. This proposed legislation would have been the only legislation of its kind in the United States; however, the bill was defeated.

A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) and Interagency Action Plan (IAP) were signed by officials of EPA, the Corps, and the Department of the Interior on June 11, 2009. The MOU and IAP outlined different administrative actions that would help decrease “the harmful environmental impacts of mountaintop mining”. The plan also includes near and long-term actions that highlight “specific steps, improved coordination, and greater transparency of decisions”.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) stated that the Clean Water Rule was completed on May 27, 2015 by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Army. The Clean Water Rule “more precisely defines waters protected under the Clean Water Act”. The EIA also stated that the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE), the EPA and the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers are collaborating with each other to make an environmental impact statement (EIS) “analyzing environmental impacts of coal surface mining in the Appalachian region”.

On Tuesday, April 9, 2019, the Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources held a legislative hearing, "Health and Environmental Impacts of Mountaintop Removal Mining". This hearing involved the H.R. 2050 (Rep. Yarmuth ) bill. This bill stated that “until health studies are conducted by the Department of Health and Human Services", there will be a suspension on permitting for mountaintop removal coal mining.

Environmental impacts

MTR negatively impacts the environment. Practices of explosion and digging release many pollutants to the surrounding environment and community and alternation of the ecosystem. Associated air pollutants such as particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide not only raise health concerns, they also have effects on all ecosystems. Air pollution contributes to issues such as water and soil acidification, chemicals bioaccumulation in the food web and eutrophication. Operations of valley fills buried more than 2,000 km of headwater and streams in the Appalachians. MTR reduces the freshwater resource that supports biodiversity. In addition, the operation provides opportunities for contamination leaching. Ca2+, Mg2+ and SO42− alter water chemistry by increasing pH, salinity and electrical conductivity. Increasing phosphorus and nitrogen can cause nutrient pollution. Selenium is toxic and can bioaccumulate. Land disturbance from forestry cutting, soil and bedrock displacement/removal and use of heavy machinery can decrease soil infiltration rate, terrestrial habitat and carbon sequestration, increase in runoff and sediment weathering. As the consequence, hydrology, geochemistry and the ecosystem's health can be permanently impacted.

2010 report

A January 2010 report in the journal Science reviews current peer-reviewed studies and water quality data and explores the consequences of mountaintop mining. It concludes that mountaintop mining has serious environmental impacts that mitigation practices cannot successfully address. For example, the extensive tracts of deciduous forests destroyed by mountaintop mining support several endangered species and some of the highest biodiversity in North America. There is a particular problem with burial of headwater streams by valley fills which causes permanent loss of ecosystems that play critical roles in ecological processes.

In addition, increases in metal ions, pH, electrical conductivity, total dissolved solids due to elevated concentrations of sulfate are closely linked to the extent of mining in West Virginia watersheds. Declines in stream biodiversity have been linked to the level of mining disturbance in West Virginia watersheds.

Published studies

Published studies also show a high potential for human health impacts. These may result from contact with streams or exposure to airborne toxins and dust. Adult hospitalization for chronic pulmonary disorders and hypertension are elevated as a result of county-level coal production. Rates of mortality, lung cancer, as well as chronic heart, lung and kidney disease are also increased. A 2011 study found that counties in and near mountaintop mining areas had higher rates of birth defects for five out of six types of birth defects, including circulatory/respiratory, musculoskeletal, central nervous system, gastrointestinal, and urogenital defects.

These defect rates were more pronounced in the most recent period studied, suggesting the health effects of mountaintop mining-related air and water contamination may be cumulative. Another 2011 study found "the odds for reporting cancer were twice as high in the mountaintop mining environment compared to the non mining environment in ways not explained by age, sex, smoking, occupational exposure, or family cancer history".

Impact statement

A United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) environmental impact statement finds that streams near some valley fills from mountaintop removal contain higher levels of minerals in the water and decreased aquatic biodiversity. Mine-affected streams also have high selenium concentrations, which can bioaccumulate and produce toxic effects (e.g., reproductive failure, physical deformity, mortality), and these effects have been documented in reservoirs below streams. Because of higher pH balances in mine-affected streams, metals such as selenium and iron hydroxide are rendered insoluble, bringing attendant chemical changes to the stream.

The statement also estimates that 724 miles (1,165 km) of Appalachian streams were buried by valley fills between 1985 and 2001. On September 28, 2010, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) independent Science Advisory Board (SAB) released their first draft review of EPA’s research into the water quality impacts of valley fills associated with mountaintop mining, agreeing with EPA’s conclusion that valley fills are associated with increased levels of conductivity threatening aquatic life in surface waters. A 2012 review by Science of the Total Environment cited elevated concentrations of SO42-, HCO3-, Ca2+ and Mg2+ downstream from VF sites. These elevated concentrations are driving factors contributing to overall increases in water conductivity. Measured conductivity values ranging from 159 to 2720 μS/cm were recorded downstream. In comparison, the reference site that did not experience MTM measured conductivity values that ranged from 30 to 260μS/cm.

Stream ecosystems

Headwater streams play a major role in the physicochemical quality of larger rivers and streams because of their close association to the surrounding landscape. They function to retain floodwaters, store nutrients and reduce sediment accumulation. VF processes limit these functions, negatively impacting surrounding rivers and watersheds. Factors contributing to disturbed stream flow include vegetation removal, subsequent aquifer formation, compaction of fill surface and overall loss of headwater streams. The removal of vegetation for mining sites reduces evapotranspiration rates from the watershed and ultimately leads to an increase in average discharge rates. Changes in flow can also be attributed to the formation of aquifers from VF that can store water entering from groundwater sources, surface run-off and precipitation. Compaction of VF sites from MTM equipment can increase the surface run-off contribution. The overall loss of headwater streams from VF practices reduces surface- groundwater connections.

Terrestrial impacts

While aquatic ecosystems and resources are vulnerable to pollution and geomorphological changes due to MTM and VF leaching, the terrestrial environment is also negatively impacted. The destruction of mountaintops results in forest loss and fragmentation. The overall loss of forest cover reduces suitable soil for revegetation efforts, carbon sequestration and biodiversity.

The Appalachian region is characterized by its high biodiversity and steep topography. The varying elevations from mountains to valleys results in subsequent varying of forest ecosystem distributions. Forest loss and fragmentation exacerbate forest community distribution by altering the terrestrial environment. Fragmentation results in an increase in edge forests and a decrease in interior forests. This is an important distinction because forest conditions vary from both classifications. Edge forests are warmer, drier, more susceptible to windier conditions and can be better suited for invasive species. As edge forests become more prevalent, biodiversity is threatened. Forest communities as well as flora and fauna diversity depend on habitats provided by old growth forests. For example, a reduction in salamander populations on reclaimed sites can be attributed to an overall loss in mesic conditions. These conditions are not present in emerging edge forests. Additionally, terrestrial changes have transformed natural forest carbon sinks into carbon sources.

Environmental effects of reclamation

Reclaimed soil generally has high bulk density and lower in infiltration rate, nutrients content and organic matter; reclaimed sites are generally not successful to reestablish the pre-mining forests that once occupied due to poor soil quality. Mine sites are often converted to non-native grassland and shrub land habitat with primarily invasive vegetation. Fast-growing, non-native flora such as Lespedeza cuneata, planted to quickly provide vegetation on a site, compete with tree seedlings, and trees have difficulty establishing root systems in compacted backfill. In addition, reintroduced elk (Cervus canadensis) on mountaintop removal sites in Kentucky are eating tree seedlings. The new ecosystem differs from the original forest habitat and can have lower diversity and productivity. A study conducted in 2017 found that herpetofaunal (reptiles and amphibians) habitat generalists are associated with all habitats, while habitat specialists are only associated with forest sites. Reclaimed grassland and shrub land are unsuitable for habitat specialists in the near future. Consequently, biodiversity suffers in a region of the United States with numerous endemic species.

Streams are reclaimed by regrading mine land, reconfiguring the mine drain, or building new stream channels in an effort to resemble the buried ones. Although the mitigation focuses on rebuilding the structure, it has not successfully restored the ecological function of the natural streams. Evidence suggests that such methods can decrease the biodiversity over time. Studies comparing the characteristics of natural and constructed channels find that constructed channels are higher in specific conductance, temperature, ion concentration and lower in organic matter, leaves breakdown rate, invertebrate density and richness. Researchers have concluded that MTR has detrimental impacts on the aquatic system and the current assessments cannot adequately evaluate the quality of the constructed channels and failed to address the functional importance of the natural stream.

Advocates

Advocates of MTR claim that once the areas are reclaimed as mandated by law, the area can provide flat land suitable for many uses in a region where flat land is at a premium. They also maintain that the new growth on reclaimed mountaintop mined areas is better suited to support populations of game animals.

While some of the land is able to be turned into grassland which game animals can live in, the amount of grassland is minimal. The land does not retake the form it had before the MTR. As stated in the book Bringing Down the Mountains: "Some of the main problems associated with MTR include soil depletion, sedimentation, low success rate of tree regrowth, lack of successful revegetation, displacement of native wildlife, and burial of streams." The ecological benefits after MTR are far below the level of the original land.

Health impacts

Published studies also show a high potential for human health impacts. These may result from contact with streams or exposure to airborne toxins and dust. Adult hospitalization for chronic pulmonary disorders and hypertension are elevated as a result of county-level coal production. Rates of mortality, lung cancer, as well as chronic heart, lung and kidney disease are also increased. A 2011 study found that counties in and near mountaintop mining areas had higher rates of birth defects for five out of six types of birth defects, including circulatory/respiratory, musculoskeletal, central nervous system, gastrointestinal, and urogenital defects.

These defect rates were more pronounced in the most recent period studied, suggesting the health effects of mountaintop mining-related air and water contamination may be cumulative. Another 2011 study found "the odds for reporting cancer were twice as high in the mountaintop mining environment compared to the non mining environment in ways not explained by age, sex, smoking, occupational exposure, or family cancer history".

Air quality

Research has shown that MTR increases human exposure to particulate matters, PAHs and crustal-derived elements. Other than occupational exposure, data and models suggested that deposits of such pollutants in lungs of the residents are significantly higher in mining areas. PM samples collected from residential sites around the mining area had higher concentrations of silica, aluminum, inorganic lithogenic components and organic matter. A comparison study that surveyed residents from both the MTR mining community and non-mining community reported that people living near the MTR site experienced more symptoms of respiratory disease. Many studies conclude that exposure to MTR environments can lead to impaired respiratory health issues. Laboratory experiments on mice also suggested that PM collected from the Appalachian MTR site can damage microvascular function that may contribute to cardiovascular disease found in the area.

Drinking water quality

MTR has negative effects on surface and ground water quality. Surface water in MTM regions has higher concentrations of arsenic, selenium, lead, magnesium, calcium, aluminum, manganese, sulfates and hydrogen sulfide from overburden. Wastewater from the coal cleaning process contains surfactants, flocculants, coal fines, benzene and toluene, sulfur, silica, iron oxide, sodium, trace metals and other chemicals. Wastewater is often injected and stored underground and has the potential to contaminate other water sources. Ground water samples from domestic wells in mining areas documented contaminations of arsenic, lead, barium, beryllium, selenium, iron, manganese, aluminum and zinc levels surpassing drinking water standards. A statistical study showed that water treatment facilities in MTR counties had significantly higher violations under the Safe Drinking Water Act compared to non-MTR counties and non-mining counties. Another study showed that ecological integrity of streams negatively correlates with cancer mortality rate in West Virginia; unhealthy streams correlates with higher cancer mortality rate. However, more studies are required on MTR impacts on public water and human health, some studies indicate the possibility of the two. Given the evidence that MTR impaired surface and ground water quality, safety of drinking water requires more efforts for protection and prevention.

Environmental justice

Poverty and mortality disparities in Central Appalachia

The Appalachian region has a long history characterized by poverty. From 2013- 2017, 6.5% to 41.0% of the population in Appalachia was impoverished. The average poverty rate for this region is 16.3%, above the national average of 14.6%. Poverty rates are directly proportional to mountaintop mining areas. Poverty rates in MTM areas were found to be significantly higher than in non-mining areas. In 2007, adult poverty rates in MTM areas were 10.1% greater than adult poverty rates in non-mining areas in Appalachia. Mortality rates show a similar relationship. Economic and health disparities are concentrated in MTM areas.

Alliance for Appalachia

The Alliance for Appalachia was established in 2006, with the mission to promote a healthy Appalachia centered around community empowerment. Today, The Alliance for Appalachia includes fifteen different member organizations working directly with impacted communities throughout Appalachia and participating in regional and federal-level campaigns. This group has been instrumental in advocating for the RECLAIM Act.

Appalachian women-led activism

Appalachian ironweed has become a symbol for the women of the Appalachian region. It represents their dedication to environmental activism and their tremendous strength to bear the burden of mountaintop mining while sustaining the grassroots fight for change. Activists like Maria Gunnoe and Maria Lambert dedicated their efforts to protect their families and their land from the adverse effects of MTM. Gunnoe and Lambert both organized and led grassroots efforts to educate their communities on the human health risks of MTM, with an emphasis on safe drinking water. Gunnoe advocated for the federal Clean Water Protection Act and continues to promote renewable energy efforts for the region. Lambert established the Prenter Water Fund which provides clean water to communities whose water has become polluted due to local MTM.

Other sites

- Laciana Valley, Spain (1994 - 2014)

Art, entertainment, and media

Short Videos

- Award-winning videographer Trip Jennings highlights communities at risk of MTR and emphasizes the importance of reviving the economy in order to create a healthy future. Communities at Risk (2015).

- The Smithsonian Channel provides an aerial visual of the extent and scale of the process of MTR. The Land of Mountaintop Removal (2013).

Documentaries

- Chet Pancake released a feature-length documentary on mountaintop removal, Black Diamonds: Mountaintop Removal and the Search for Coalfield Justice (2006), a selection in the Documentary Fortnight at the Museum of Modern Art. The film features Julia Bonds, who won the 2003 Goldman Environmental Prize.

- The documentary, Mountain Top Removal (2007), focuses on Mountain Justice Summer activists, coal field residents, and coal industry officials. On April 18, 2008, the film received the Reel Current award selected and was presented by Al Gore at the Nashville Film Festival.

- The feature documentary, Burning the Future: Coal in America (2008), was awarded the International Documentary Association's 2008 Pare Lorentz award for Best Documentary.

- The Last Mountain (2011), directed by Bill Haney, details the effects on the land and people living near mountaintop removal and coal burning sites. Maria Gunnoe, the 2009 Goldman Environmental Prize winner, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., and others present the devastation, confront the politicians and corporate interests, and offer wind power as one solution for Coal River Mountain, West Virginia.

- The autoethnographic documentary film Goodbye Gauley Mountain: An Ecosexual Love Story (2013), by Beth Stephens with Annie Sprinkle, raises awareness on the issue of mountain top removal in West Virginia by bringing together environmental activism, performance art, and queer activism against the issue. Stephens says: "My hope for this film, is that in addition to it being a compelling story, it will inspire and raise awareness in groups of people not normally associated with the environmental movement, and especially in LGBTQ communities. There are relatively few films about environmental issues that feature out queers."

Non-fiction books

- In April 2005, a group of Kentucky writers traveled together to see the devastation from mountaintop removal mining, and Wind Publishing produced the resulting collection of poems, essays and photographs, co-edited by Kristin Johannesen, Bobbie Ann Mason, and Mary Ann Taylor-Hall in Missing Mountains: We went to the mountaintop, but it wasn't there.

- Dr. Shirley Stewart Burns, a West Virginia coalfield native, wrote the first academic work on mountaintop removal, titled Bringing Down The Mountains (2007), which is loosely based on her internationally award-winning 2005 Ph.D. dissertation of the same name.

- Dr. Burns was also a co-editor, with Kentucky author Silas House and filmmaker Mari-Lynn Evans, of Coal Country (2009), a companion book for the nationally recognized feature-length film of the same name.

- House, Silas & Howard, Jason (2009). Something's Rising: Appalachians Fighting Mountaintop Removal.

- Howard, Jason (Editor) (2009). We All Live Downstream: Writings about Mountaintop Removal.

- Dr. Rebecca Scott, another native West Virginian, examined the sociological relationship of identity and natural resource extraction in central Appalachia in her book, Removing Mountains (2010).

- Hedges, Chris; Sacco, Joe (2012). Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt. Chapter 3. "Days of Devastation: Welch, West Virginia."

- Cultural historian Jeff Biggers published The United States of Appalachia, which examined the cultural and human costs of mountaintop removal.

Additionally, many personal interest stories of coalfield residents have been written, including:

- Lost Mountain: A Year in the Vanishing Wilderness—Radical Strip Mining and the Devastation of Appalachia (2006) by Erik Reese

- Moving Mountains: How One Woman and Her Community Won Justice from Big Coal (2007) by Penny Loeb

Fiction books

- Mountaintop removal is a major plot element of Jonathan Franzen's best-selling novel Freedom (2010), wherein a major character helps to secure land for surface mining with the promise that it will be restored and turned into a nature reserve.

- Same Sun Here by Silas House and Neela Vaswani is a novel for middle grade readers that deals with issues of mountaintop removal and is set over the course of one school year 2008-2009.

- In John Grisham's novel Gray Mountain (2014), Samantha Kofer moves from a large Wall Street law firm to a small Appalachian town where she confronts the world of coal mining.

Music

- Caroline Herring's song "Black Mountain Lullaby" (on the album Camilla, 2012) is based on the story of Jeremy Davidson, age 3, who was killed by a mountaintop mining accident in 2004. She was inspired to write the song after reading an editorial about mountaintop removal written by Silas House that appeared in the New York Times on 19 February 2011.

- Lissie's album Back to Forever contains a moving protest song on the topic called simply "Mountaintop Removal".

- Liam Wilson of The Dillinger Escape Plan wore a homemade shirt saying "stop mtm/vf" during the band's performance on Late Night with Conan O'Brien.

- Jean Ritchie's song "Black Waters" describes the horror of coal mining in the Appalachians.

- John Prine's song "Paradise" addresses the impacts of strip mining in Appalachia, referencing the impacts of the technique on the Green River area in Kentucky.

- In 2010, David Rovics wrote and performed a song titled "Hills of Tennessee", lamenting the tragedy of mountaintop removal mining near Nashville.

- In 2010, a concert series titled "Music Saves Mountains" raised funds and awareness for mountaintop removal, featuring artists Ben Sollee, Big Kenny, Buddy Miller, Dave Matthews, Emmylou Harris, Gloriana, Kathy Mattea, Naomi Judd, Patty Griffin, Patty Loveless, and Alison Krauss.