From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Republic (Greek: Πολιτεία, translit. Politeia; Latin: De Republica[1]) is a Socratic dialogue, authored by Plato around 375 BC, concerning justice (δικαιοσύνη), the order and character of the just city-state, and the just man.[2] It is Plato's best-known work, and has proven to be one of the world's most influential works of philosophy and political theory, both intellectually and historically.[3][4]

In the dialogue, Socrates

talks with various Athenians and foreigners about the meaning of

justice and whether the just man is happier than the unjust man.[5]

They consider the natures of existing regimes and then propose a

series of different, hypothetical cities in comparison, culminating in

Kallipolis (Καλλίπολις), a utopian city-state ruled by a philosopher-king. They also discuss the theory of forms, the immortality of the soul, and the role of the philosopher and of poetry in society.[6] The dialogue's setting seems to be during the Peloponnesian War.[7]

Structure

By book

Book I

While visiting the Piraeus with Glaucon, Polemarchus tells Socrates to join him for a romp. Socrates then asks Cephalus, Polemarchus, and Thrasymachus

their definitions of justice. Cephalus defines justice as giving what

is owed. Polemarchus says justice is "the art which gives good to

friends and evil to enemies." Thrasymachus proclaims "justice is nothing

else than the interest of the stronger." Socrates overturns their

definitions and says that it is to one's advantage to be just and

disadvantage to be unjust. The first book ends in aporia concerning its essence.

Book II

Socrates believes he has answered Thrasymachus and is done with the discussion of justice.

Socrates' young companions, Glaucon and Adeimantus,

continue the argument of Thrasymachus for the sake of furthering the

discussion. Glaucon gives a lecture in which he argues first that the

origin of justice was in social contracts aimed at preventing one from

suffering injustice and being unable to take revenge, second that all

those who practice justice do so unwillingly and out of fear of

punishment, and third that the life of the unjust man is far more

blessed than that of the just man. Glaucon would like Socrates to prove

that justice is not only desirable, but that it belongs to the highest

class of desirable things: those desired both for their own sake and

their consequences. To demonstrate the problem, he tells the story of Gyges, who – with the help of a ring that turns him invisible – achieves great advantages for himself by committing injustices.

After Glaucon's speech, Adeimantus

adds that, in this thought experiment, the unjust should not fear any

sort of divine judgement in the afterlife, since the very poets who

wrote about such judgement also wrote that the gods would grant

forgiveness to those humans who made ample religious sacrifice.

Adeimantus demonstrates his reason by drawing two detailed portraits,

that the unjust man could grow wealthy by injustice, devoting a

percentage of this gain to religious losses, thus rendering him innocent

in the eyes of the gods.

Socrates suggests that they look for justice in a city rather

than in an individual man. After attributing the origin of society to

the individual not being self-sufficient and having many needs which he

cannot supply himself, they go on to describe the development of the

city. Socrates first describes the "healthy state", but Glaucon asks him

to describe "a city of pigs", as he finds little difference between the

two. He then goes on to describe the luxurious city, which he calls "a

fevered state".[8] This requires a guardian class

to defend and attack on its account. This begins a discussion

concerning the type of education that ought to be given to these

guardians in their early years, including the topic of what kind of

stories are appropriate. They conclude that stories that ascribe evil

to the gods are untrue and should not be taught.

Book III

Socrates and his companions Adeimantus and Glaucon conclude their discussion concerning education. Socrates breaks the educational system into two. They suggest that guardians should be educated in these four cardinal virtues:

wisdom, courage, justice and temperance. They also suggest that the

second part of the guardians' education should be in gymnastics. With

physical training they will be able to live without needing frequent

medical attention: physical training will help prevent illness and

weakness. Socrates asserts that both male and female guardians be given

the same education, that all wives and children be shared, and that they

be prohibited from owning private property.

In the fictional tale known as the myth or parable of the metals,

Socrates presents the Noble Lie

(γενναῖον ψεῦδος, gennaion pseudos), to explain the origin of the three

social classes. Socrates proposes and claims that if the people

believed "this myth...[it] would have a good effect, making them more

inclined to care for the state and one another."[9]

Book IV

Socrates

and his companions conclude their discussion concerning the lifestyle

of the guardians, thus concluding their initial assessment of the city

as a whole. Socrates assumes each person will be happy engaging in the

occupation that suits them best. If the city as a whole is happy, then

individuals are happy. In the physical education and diet of the

guardians, the emphasis is on moderation, since both poverty and

excessive wealth will corrupt them (422a1). Without controlling their

education, the city cannot control the future rulers. Socrates says that

it is pointless to worry over specific laws, like those pertaining to

contracts, since proper education ensures lawful behavior, and poor

education causes lawlessness (425a–425c).[10]

Socrates proceeds to search for wisdom, courage, and temperance

in the city, on the grounds that justice will be easier to discern in

what remains (427e). They find wisdom among the guardian rulers, courage

among the guardian warriors (or auxiliaries), temperance among all

classes of the city in agreeing about who should rule and who should be

ruled. Finally, Socrates defines justice in the city as the state in

which each class performs only its own work, not meddling in the work of

the other classes (433b).

The virtues discovered in the city are then sought in the

individual soul. For this purpose, Socrates creates an analogy between

the parts of the city and the soul (the city–soul analogy). He argues

that psychological conflict points to a divided soul, since a completely

unified soul could not behave in opposite ways towards the same object,

at the same time, and in the same respect (436b).[11] He gives examples of possible conflicts between the rational, spirited, and appetitive parts of the soul, corresponding to the rulers, auxiliaries, and producing classes in the city.

Having established the tripartite soul, Socrates defines the

virtues of the individual. A person is wise if he is ruled by the part

of the soul that knows “what is beneficial for each part and for the

whole,” courageous if his spirited part “preserves in the midst of

pleasures and pains” the decisions reached by the rational part, and

temperate if the three parts agree that the rational part lead (442c–d).[12]

They are just if each part of the soul attends to its function and not

the function of another. It follows from this definition that one cannot

be just if one doesn't have the other cardinal virtues.[11]

Book V

Socrates,

having to his satisfaction defined the just constitution of both city

and psyche, moves to elaborate upon the four unjust constitutions of

these. Adeimantus and Polemarchus interrupt, asking Socrates instead

first to explain how the sharing of wives and children in the guardian

class is to be defined and legislated, a theme first touched on in Book

III. Socrates is overwhelmed at their request, categorizing it as three

"waves" of attack against which his reasoning must stand firm. These

three waves challenge Socrates' claims that

- both male and female guardians ought to receive the same education

- human reproduction ought to be regulated by the state and all offspring should be ignorant of their actual biological parents

- such a city and its corresponding philosopher-king could actually come to be in the real world.

Book VI

Socrates'

argument is that in the ideal city, a true philosopher with

understanding of forms will facilitate the harmonious co-operation of

all the citizens of the city—the governance of a city-state is likened to the command of a ship, the Ship of State.

This philosopher-king must be intelligent, reliable, and willing to

lead a simple life. However, these qualities are rarely manifested on

their own, and so they must be encouraged through education and the

study of the Good. Just as visible objects must be illuminated in order

to be seen, so must also be true of objects of knowledge if light is

cast on them.

Book VII

Socrates elaborates upon the immediately preceding Analogies of the Sun and of the Divided Line in the Allegory of the Cave,

in which he insists that the psyche must be freed from bondage to the

visible/sensible world by making the painful journey into the

intelligible world. He continues in the rest of this book by further

elaborating upon the curriculum which a would-be philosopher-king must

study. This is the origin of the quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music.

Next, they elaborate on the education of the philosopher-king.

Until age 18, would-be guardians should be engaged in basic intellectual

study and physical training, followed by two years of military

training. However, a correction is then introduced where the study of

gymnastics (martial arts) and warfare – 3 plus 2 years, respectively –

are supplanted by philosophy for 5 years instead. Next, they receive ten

years of mathematics until age 30, and then five years of dialectic

training. Guardians then spend the next 15 years as leaders, trying to

"lead people from the cave". Upon reaching 50, they are fully aware of

the form of good, and totally mature and ready to lead.

Book VIII

Socrates discusses four unjust constitutions: timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny.

He argues that a society will decay and pass through each government in

succession, eventually becoming a tyranny, the most unjust regime of

all.

The starting point is an imagined, alternate aristocracy

(ruled by a philosopher-king); a just government dominated by the

wisdom-loving element. When its social structure breaks down and enters

civil war, it is replaced by timocracy. The timocratic government is

dominated by the spirited element, with a ruling class of

property-owners consisting of warriors or generals (Ancient Sparta

is an example). As the emphasis on honor is compromised by wealth

accumulation, it is replaced by oligarchy. The oligarchic government is

dominated by the desiring element, in which the rich are the ruling

class. The gap between rich and poor widens, culminating in a revolt by

the underclass majority, establishing a democracy. Democracy emphasizes

maximum freedom, so power is distributed evenly. It is also dominated by

the desiring element, but in an undisciplined, unrestrained way. The

populism of the democratic government leads to mob rule, fueled by fear

of oligarchy, which a clever demagogue

can exploit to take power and establish tyranny. In a tyrannical

government, the city is enslaved to the tyrant, who uses his guards to

remove the best social elements and individuals from the city to retain

power (since they pose a threat), while leaving the worst. He will also

provoke warfare to consolidate his position as leader. In this way,

tyranny is the most unjust regime of all.

In parallel to this, Socrates considers the individual or soul

that corresponds to each of these regimes. He describes how an

aristocrat may become weak or detached from political and material

affluence, and how his son will respond to this by becoming overly

ambitious. The timocrat in turn may be defeated by the courts or vested

interests; his son responds by accumulating wealth in order to gain

power in society and defend himself against the same predicament,

thereby becoming an oligarch. The oligarch's son will grow up with

wealth without having to practice thrift or stinginess, and will be

tempted and overwhelmed by his desires, so that he becomes democratic,

valuing freedom above all.

Book IX

Having

discussed the tyrannical constitution of a city, Socrates wishes to

discuss the tyrannical constitution of a psyche. This is all intended to

answer Thrasymachus' first argument in Book I, that the life of the

unjust man (here understood as a true tyrant) is more blessed than that

of the just man (the philosopher-king).

First, he describes how a tyrannical man develops from a

democratic household. The democratic man is torn between tyrannical

passions and oligarchic discipline, and ends up in the middle ground:

valuing all desires, both good and bad. The tyrant will be tempted in

the same way as the democrat, but without an upbringing in discipline or

moderation to restrain him. Therefore, his most base desires and

wildest passions overwhelm him, and he becomes driven by lust, using

force and fraud to take whatever he wants. The tyrant is both a slave to

his lusts, and a master to whomever he can enslave.

Because of this, tyranny is the regime with the least freedom and

happiness, and the tyrant is most unhappy of all, since the regime and

soul correspond. His desires are never fulfilled, and he always must

live in fear of his victims. Because the tyrant can only think in terms

of servant and master, he has no equals whom he can befriend, and with

no friends the tyrant is robbed of freedom. This is the first proof that

it is better to be just than unjust. The second proof is derived from

the tripartite theory of soul. The wisdom-loving soul is best equipped

to judge what is best through reason, and the wise individual judges

wisdom to be best, then honor, then desire. This is the just proportion

for the city or soul and stands opposite to tyranny, which is entirely

satiated on base desires. The third proof follows from this. He

describes how the soul can be misled into experiencing false pleasure:

for example, a lack of pain can seem pleasurable by comparison to a

worse state. True pleasure is had by being fulfilled by things that fit

one's nature. Wisdom is the most fulfilling and is the best guide, so

the only way for the three drives of the soul to function properly and

experience the truest pleasure is by allowing wisdom to lead. To

conclude the third proof, the wisdom element is best at providing

pleasure, while tyranny is worst because it is furthest removed from

wisdom.

Finally, Socrates considers the multiple of how much worse

tyranny is than the kingly/disciplined/wise temperament, and even

quantifies the tyrant as living 729 times more painfully/less joyfully

than the king. He then gives the example of a chimera to further

illustrate justice and the tripartite soul.

The discussion concludes by refuting Thrasymachus' argument and

designating the most blessed life as that of the just man and the most

miserable life as that of the unjust man.

Book X

Concluding a theme brought up most explicitly in the Analogies of the Sun and Divided Line in Book VI, Socrates finally rejects any form of imitative art

and concludes that such artists have no place in the just city. He

continues on to argue for the immortality of the psyche and even

espouses a theory of reincarnation.

He finishes by detailing the rewards of being just, both in this life

and the next. Artists create things but they are only different copies

of the idea of the original.

"And whenever any one informs us that he has found a man who knows all

the arts, and all things else that anybody knows, and every single thing

with a higher degree of accuracy than any other man—whoever tells us

this, I think that we can only imagine to be a simple creature who is

likely to have been deceived by some wizard or actor whom he met, and

whom he thought all-knowing, because he himself was unable to analyze

the nature of knowledge and ignorance and imitation."[13]

"And the same object appears straight when looked at out of the

water, and crooked when in the water; and the concave becomes convex,

owing to the illusion about colours to which the sight is liable. Thus

every sort of confusion is revealed within us; and this is that weakness

of the human mind on which the art of conjuring and deceiving by light

and shadow and other ingenious devices imposes, having an effect upon us

like magic."[13]

He speaks about illusions and confusion. Things can look very

similar, but be different in reality. Because we are human, at times we

cannot tell the difference between the two.

"And does not the same hold also of the ridiculous? There are

jests which you would be ashamed to make yourself, and yet on the comic

stage, or indeed in private, when you hear them, you are greatly amused

by them, and are not at all disgusted at their unseemliness—the case of

pity is repeated—there is a principle in human nature which is disposed

to raise a laugh, and this which you once restrained by reason, because

you were afraid of being thought a buffoon, is now let out again; and

having stimulated the risible faculty at the theatre, you are betrayed

unconsciously to yourself into playing the comic poet at home."

With all of us, we may approve of something, as long we are not

directly involved with it. If we joke about it, we are supporting it.

"Quite true, he said.

And the same may be said of lust and anger and all the other affections,

of desire and pain and pleasure, which are held to be inseparable from

every action—in all of them poetry feeds and waters the passions instead

of drying them up; she lets them rule, although they ought to be

controlled, if mankind are ever to increase in happiness and virtue."[13]

Sometimes we let our passions rule our actions or way of

thinking, although they should be controlled, so that we can increase

our happiness.

Scholarly views

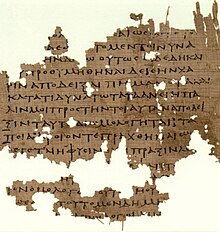

P. Oxy. 3679, manuscript from the 3rd century AD, containing fragments of Plato's Republic.

Three interpretations of the Republic are presented in the

following section; they are not exhaustive in their treatments of the

work, but are examples of contemporary interpretation.

Bertrand Russell

In his A History of Western Philosophy (1945), Bertrand Russell identifies three parts to the Republic:[14]

- Books I–V: from the attempt to define justice, the description of an ideal community (a "utopia") and the education of its Guardians;

- Books VI–VII: the nature of philosophers, the ideal rulers of such a community;

- Books VIII–X: the pros and cons of various practical forms of government.

The core of the second part is the Allegory of the Cave and the discussion of the theory of ideal forms. The third part concerns the Five Regimes and is strongly related to the later dialogue The Laws; and the Myth of Er.

Cornford, Hildebrandt, and Voegelin

Francis Cornford, Kurt Hildebrandt [de], and Eric Voegelin contributed to an establishment of sub-divisions marked with special formulae in Greek:

- Prologue

- I.1. 327a–328b. Descent to the Piraeus

- I.2–I.5. 328b–331d. Cephalus. Justice of the older generation

- I.6–1.9. 331e–336a. Polemarchus. Justice of the middle generation

- I.10–1.24. 336b–354c. Thrasymachus. Justice of the sophist

- Introduction

- II.1–II.10. 357a–369b. The question: Is justice better than injustice?

- Part I

- Genesis and order of the polis: II.11–II.16. 369b–376e. Genesis of the polis

- II.16–III.18. 376e–412b. Education of the guardians

- III.19–IV.5. 412b–427c. Constitution of the polis

- IV.6–IV.19. 427c–445e. Justice in the polis

- Part II

- Embodiment of the idea: V.1–V.16. 449a–471c. Somatic unity of polis and the Hellenes

- V.17–VI.14. 471c–502c. Rule of the philosophers

- VI.19–VII.5. 502c–521c. The Idea of the Agathon

- VII.6–VII.18. 521c–541b. Education of the philosophers

- Part III

- Decline of the polis: VIII.1–VIII.5. 543a–550c. Timocracy

- VIII.6–VIII.9. 550c–555b. Oligarchy

- VIII.10–VIII.13. 555b–562a. Democracy

- VIII.14–IX.3. 562a–576b. Tyranny

- Conclusion

- IX.4–IX.13. 576b–592b Answer: Justice is better than injustice.

- Epilogue

- X.1–X.8. 595a–608b. Rejection of mimetic art

- X.9–X.11. 608c–612a. Immortality of the soul

- X.12. 612a–613e. Rewards of justice in life

- X.13–X.16. 613e–621d. Judgment of the dead

The paradigm of the city—the idea of the Good, the Agathon—has

manifold historical embodiments, undertaken by those who have seen the

Agathon, and are ordered via the vision. The centerpiece of the Republic, Part II, nos. 2–3, discusses the rule of the philosopher, and the vision of the Agathon with the Allegory of the Cave, which is clarified in the theory of forms. The centerpiece is preceded and followed by the discussion of the means that will secure a well-ordered polis

(city). Part II, no. 1, concerns marriage, the community of people and

goods for the guardians, and the restraints on warfare among the

Hellenes. It describes a partially communistic polis.

Part II, no. 4, deals with the philosophical education of the rulers

who will preserve the order and character of the city-state.

In part II, the Embodiment of the Idea, is preceded by the establishment of the economic and social orders of a polis

(part I), followed by an analysis (part III) of the decline the order

must traverse. The three parts compose the main body of the dialogues,

with their discussions of the "paradigm", its embodiment, its genesis,

and its decline.

The introduction and the conclusion are the frame for the body of the Republic.

The discussion of right order is occasioned by the questions: "Is

justice better than injustice?" and "Will an unjust man fare better than

a just man?" The introductory question is balanced by the concluding

answer: "Justice is preferable to injustice". In turn, the foregoing are

framed with the Prologue (Book I) and the Epilogue (Book X). The prologue is a short dialogue about the common public doxai (opinions) about justice. Based upon faith, and not reason, the Epilogue describes the new arts and the immortality of the soul.

Leo Strauss

Leo Strauss identified a four-part structure to the Republic,[citation needed]

perceiving the dialogues as a drama enacted by particular characters,

each with a particular perspective and level of intellect:

- Book I: Socrates is forcefully compelled to the house of

Cephalus. Three definitions of justice are presented, all are found

lacking.

- Books II–V: Glaucon and Adeimantus

challenge Socrates to prove why a perfectly just man, perceived by the

world as an unjust man, would be happier than the perfectly unjust man

who hides his injustice and is perceived by the world as a just man.

Their challenge begins and propels the dialogues; in answering the

challenge, of the "charge", Socrates reveals his behavior with the young

men of Athens, whom he later was convicted of corrupting. Because

Glaucon and Adeimantus presume a definition of justice, Socrates

digresses; he compels the group's attempt to discover justice, and then

answers the question posed to him about the intrinsic value of the just

life.

- Books V–VI: The "Just City in Speech" is built from the earlier

books, and concerns three critiques of the city. Leo Strauss reported

that his student Allan Bloom

identified them as: communism, communism of wives and children, and the

rule of philosophers. The "Just City in Speech" stands or falls by

these complications.

- Books VII–X: Socrates has "escaped" his captors, having momentarily

convinced them that the just man is the happy man, by reinforcing their

prejudices. He presents a rationale for political decay, and concludes

by recounting The Myth of Er ("everyman"), consolation for non-philosophers who fear death.[citation needed]

Topics

Definition of justice

In the first book, two definitions of justice are proposed but deemed inadequate.[15]

Returning debts owed, and helping friends while harming enemies, are

commonsense definitions of justice that, Socrates shows, are inadequate

in exceptional situations, and thus lack the rigidity demanded of a definition.

Yet he does not completely reject them, for each expresses a

commonsense notion of justice that Socrates will incorporate into his

discussion of the just regime in books II through V.

At the end of Book I, Socrates agrees with Polemarchus that

justice includes helping friends, but says the just man would never do

harm to anybody. Thrasymachus believes that Socrates has done the men

present an injustice by saying this and attacks his character and

reputation in front of the group, partly because he suspects that

Socrates himself does not even believe harming enemies is unjust.

Thrasymachus gives his understanding of justice and injustice as

"justice is what is advantageous to the stronger, while injustice is to

one's own profit and advantage".[16]

Socrates finds this definition unclear and begins to question

Thrasymachus. Socrates then asks whether the ruler who makes a mistake

by making a law that lessens their well-being, is still a ruler

according to that definition. Thrasymachus agrees that no true ruler

would make such an error. This agreement allows Socrates to undermine

Thrasymachus' strict definition of justice by comparing rulers to people

of various professions. Thrasymachus consents to Socrates' assertion

that an artist is someone who does his job well, and is a knower of some

art, which allows him to complete the job well. In so doing Socrates

gets Thrasymachus to admit that rulers who enact a law that does not

benefit them firstly, are in the precise sense not rulers.

Thrasymachus gives up, and is silent from then on. Socrates has trapped

Thrasymachus into admitting the strong man who makes a mistake is not

the strong man in the precise sense, and that some type of knowledge is

required to rule perfectly. However, it is far from a satisfactory

definition of justice.

At the beginning of Book II, Plato's two brothers challenge

Socrates to define justice in the man, and unlike the rather short and

simple definitions offered in Book I, their views of justice are

presented in two independent speeches. Glaucon's speech reprises

Thrasymachus' idea of justice; it starts with the legend of Gyges, who discovered a ring (the so-called Ring of Gyges)

that gave him the power to become invisible. Glaucon uses this story to

argue that no man would be just if he had the opportunity of doing

injustice with impunity.

With the power to become invisible, Gyges is able to seduce the queen,

murder the king, and take over the kingdom. Glaucon argues that the just

as well as the unjust man would do the same if they had the power to

get away with injustice exempt from punishment. The only reason that men

are just and praise justice is out of fear of being punished for

injustice. The law is a product of compromise between individuals who

agree not to do injustice to others if others will not do injustice to

them. Glaucon says that if people had the power to do injustice without

fear of punishment, they would not enter into such an agreement. Glaucon

uses this argument to challenge Socrates to defend the position that

the just life is better than the unjust life. Adeimantus adds to

Glaucon's speech the charge that men are only just for the results that

justice brings one fortune, honor, reputation. Adeimantus challenges

Socrates to prove that being just is worth something in and of itself,

not only as a means to an end.

Socrates says that there is no better topic to debate. In

response to the two views of injustice and justice presented by Glaucon

and Adeimantus, he claims incompetence, but feels it would be impious to

leave justice in such doubt. Thus the Republic sets out to define justice. Given the difficulty of this task as proven in Book I, Socrates

in Book II leads his interlocutors into a discussion of justice in the

city, which Socrates suggests may help them see justice not only in the

person, but on a larger scale, "first in cities searching for what it

is; then thusly we could examine also in some individual, examining the

likeness of the bigger in the idea of the littler" (368e–369a).[17]

For over two and a half millennia, scholars have differed on the

aptness of the city–soul analogy Socrates uses to find justice in Books

II through V.[18] The Republic

is a dramatic dialogue, not a treatise. Socrates' definition of justice

is never unconditionally stated, only versions of justice within each

city are "found" and evaluated in Books II through Book V. Socrates

constantly refers the definition of justice back to the conditions of

the city for which it is created. He builds a series of myths, or noble lies,

to make the cities appear just, and these conditions moderate life

within the communities. The "earth born" myth makes all men believe that

they are born from the earth and have predestined natures within their

veins. Accordingly, Socrates defines justice as "working at that to

which he is naturally best suited", and "to do one's own business and

not to be a busybody" (433a–433b) and goes on to say that justice

sustains and perfects the other three cardinal virtues:

Temperance, Wisdom, and Courage, and that justice is the cause and

condition of their existence. Socrates does not include justice as a

virtue within the city, suggesting that justice does not exist within

the human soul either, rather it is the result of a "well ordered" soul.

A result of this conception of justice separates people into three

types; that of the soldier, that of the producer, and that of a ruler.

If a ruler can create just laws, and if the warriors can carry out the

orders of the rulers, and if the producers can obey this authority, then

a society will be just.

The city is challenged by Adeimantus and Glaucon throughout its

development: Adeimantus cannot find happiness in the city, and Glaucon

cannot find honor and glory. This hypothetical city contains no private

property, no marriage, or nuclear families. These are sacrificed for the

common good and doing what is best fitting to one's nature. In Book V

Socrates addresses the question of "natural-ness" of and possibility for

this city, concluding in Book VI, that the city's ontological status

regards a construction of the soul, not of an actual metropolis.

The rule of philosopher-kings

appear as the issue of possibility is raised. Socrates never positively

states what justice is in the human soul/city; it appears he has

created a city where justice is not found, but can be lost. It is as

though in a well-ordered state, justice is not even needed, since the

community satisfies the needs of humans.

In terms of why it is best to be just rather than unjust for the

individual, Plato prepares an answer in Book IX consisting of three main

arguments. Plato says that a tyrant's nature will leave him with

"horrid pains and pangs" and that the typical tyrant engages in a

lifestyle that will be physically and mentally exacting on such a ruler.

Such a disposition is in contrast to the truth-loving

philosopher-king, and a tyrant "never tastes of true freedom or

friendship". The second argument proposes that of all the different

types of people, only the philosopher is able to judge which type of

ruler is best since only he can see the Form of the Good.

Thirdly, Plato argues, "Pleasures which are approved of by the lover

of wisdom and reason are the truest." In sum, Plato argues that

philosophical pleasure is the only true pleasure since other pleasures

experienced by others are simply a neutral state free of pain.

Socrates points out the human tendency to be corrupted by power leads down the road to timocracy, oligarchy, democracy and tyranny.

From this, he concludes that ruling should be left to philosophers, who

are the most just and therefore least susceptible to corruption. This

"good city" is depicted as being governed by philosopher-kings;

disinterested persons who rule not for their personal enjoyment but for

the good of the city-state (polis). The philosophers have seen

the "Forms" and therefore know what is good. They understand the

corrupting effect of greed and own no property and receive no salary.

They also live in sober communism, eating and sleeping together.

The paradigmatic society which stands behind every historical

society is hierarchical, but social classes have a marginal

permeability; there are no slaves, no discrimination between men and

women. The men and women are both to be taught the same things, so they

are both able to be used for the same things (451e). In addition to the

ruling class of guardians (φύλακες), which abolished riches, there is a class of private producers (demiourgoi),

who may be rich or poor. A number of provisions aim to avoid making the

people weak: the substitution of a universal educational system for men

and women instead of debilitating music, poetry and theatre—a startling

departure from Greek society. These provisions apply to all classes,

and the restrictions placed on the philosopher-kings chosen from the

warrior class and the warriors are much more severe than those placed on

the producers, because the rulers must be kept away from any source of

corruption.

In Books V-VI the abolition of riches among the guardian class

(not unlike Max Weber's bureaucracy) leads controversially to the

abandonment of the typical family, and as such no child may know his or

her parents and the parents may not know their own children. Socrates

tells a tale which is the "allegory

of the good government". The rulers assemble couples for reproduction,

based on breeding criteria. Thus, stable population is achieved through

eugenics and social cohesion is projected to be high because familial

links are extended towards everyone in the city. Also the education of

the youth is such that they are taught of only works of writing that

encourage them to improve themselves for the state's good, and envision

(the) god(s) as entirely good, just, and the author(s) of only that

which is good.

In Books VII-X stand Plato's criticism of the forms of

government. It begins with the dismissal of timocracy, a sort of

authoritarian regime, not unlike a military dictatorship. Plato offers

an almost psychoanalytical explanation of the "timocrat" as one who saw

his father humiliated by his mother and wants to vindicate "manliness".

The third worst regime is oligarchy, the rule of a small band of rich

people, millionaires that only respect money. Then comes the democratic

form of government, and its susceptibility to being ruled by unfit

"sectarian" demagogues. Finally the worst regime is tyranny, where the

whimsical desires of the ruler became law and there is no check upon

arbitrariness.

Theory of universals

The Republic contains Plato's Allegory of the Cave with which he explains his concept of the Forms as an answer to the problem of universals.

The Allegory of the Cave primarily depicts Plato's distinction

between the world of appearances and the 'real' world of the Forms,[19]

as well as helping to justify the philosopher's place in society as

king. Plato imagines a group of people who have lived their entire lives

as prisoners, chained to the wall of a cave in the subterranean so they

are unable to see the outside world behind them. However a constant

flame illuminates various moving objects outside, which are silhouetted

on the wall of the cave visible to the prisoners. These prisoners,

through having no other experience of reality, ascribe forms to these

shadows such as either "dog" or "cat".

Plato then goes on to explain how the philosopher is akin to a

prisoner who is freed from the cave. The prisoner is initially blinded

by the light, but when he adjusts to the brightness he sees the fire and

the statues and how they caused the images witnessed inside the cave.

He sees that the fire and statues in the cave were just copies of the

real objects; merely imitations. This is analogous to the Forms. What we

see from day to day are merely appearances, reflections of the Forms.

The philosopher, however, will not be deceived by the shadows and will

hence be able to see the 'real' world, the world above that of

appearances; the philosopher will gain knowledge of things in

themselves. In this analogy the sun is representative of the Good. This

is the main object of the philosopher's knowledge. The Good can be

thought of as the form of Forms, or the structuring of the world as a

whole.

The prisoner's stages of understanding correlate with the levels on the divided line

which he imagines. The line is divided into what the visible world is

and what the intelligible world is, with the divider being the Sun. When

the prisoner is in the cave, he is obviously in the visible realm that

receives no sunlight, and outside he comes to be in the intelligible

realm.

The shadows witnessed in the cave correspond to the lowest level

on Plato's line, that of imagination and conjecture. Once the prisoner

is freed and sees the shadows for what they are he reaches the second

stage on the divided line, the stage of belief, for he comes to believe

that the statues in the cave are real. On leaving the cave, however, the

prisoner comes to see objects more real than the statues inside of the

cave, and this correlates with the third stage on Plato's line, thought.

Lastly, the prisoner turns to the sun which he grasps as the source of

truth, or the Form of the Good, and this last stage, named as dialectic,

is the highest possible stage on the line. The prisoner, as a result of

the Form of the Good, can begin to understand all other forms in

reality.

At the end of this allegory, Plato asserts that it is the

philosopher's burden to reenter the cave. Those who have seen the ideal

world, he says, have the duty to educate those in the material world.

Since the philosopher recognizes what is truly good only he is fit to

rule society according to Plato.

Dialectical forms of government

While Plato spends much of the Republic having Socrates

narrate a conversation about the city he founds with Glaucon and

Adeimantus "in speech", the discussion eventually turns to considering

four regimes that exist in reality and tend to degrade successively into

each other: timocracy, oligarchy (also called plutocracy), democracy

and tyranny (also called despotism).

Timocracy

Socrates defines a timocracy

as a government of people who love rule and honor. Socrates argues that

the timocracy emerges from aristocracy due to a civil war breaking out

among the ruling class and the majority. Over time, many more births

will occur to people who lack aristocratic, guardian qualities, slowly

drawing the populace away from knowledge, music, poetry and "guardian

education", toward money-making and the acquisition of possessions. This

civil war between those who value wisdom and those who value material

acquisition will continue until a compromise is reached. The timocracy

values war insofar as it satisfies a love of victory and honor. The

timocratic man loves physical training, and hunting, and values his

abilities in warfare.

Oligarchy

Temptations create a confusion between economic status and honor which is responsible for the emergence of oligarchy.

In Book VIII, Socrates suggests that wealth will not help a pilot to

navigate his ship, as his concerns will be directed centrally toward

increasing his wealth by whatever means, rather than seeking out wisdom

or honor. The injustice of economic disparity divides the rich and the

poor, thus creating an environment for criminals and beggars to emerge.

The rich are constantly plotting against the poor and vice versa. The

oligarchic constitution is based on property assessment and wealth

qualification. Unlike the timocracy, oligarchs are also unable to fight

war, since they do not wish to arm the majority for fear of their rising

up against them (fearing the majority even more than their enemies),

nor do they seem to pay mercenaries, since they are reluctant to spend

money.

Democracy

As this socioeconomic divide grows, so do tensions between social

classes. From the conflicts arising out of such tensions, the poor

majority overthrow the wealthy minority, and democracy

replaces the oligarchy preceding it. The poor overthrow the oligarchs

and grant liberties and freedoms to citizens, creating a most variegated

collection of peoples under a "supermarket" of constitutions. A

visually appealing demagogue

is soon lifted up to protect the interests of the lower class. However,

with too much freedom, no requirements for anyone to rule, and having

no interest in assessing the background of their rulers (other than

honoring such people because they wish the majority well) the people

become easily persuaded by such a demagogue's appeal to try to satisfy

people's common, base, and unnecessary pleasures.

Tyranny

The excessive freedoms granted to the citizens of a democracy ultimately leads to a tyranny,

the furthest regressed type of government. These freedoms divide the

people into three socioeconomic classes: the dominating class, the

elites and the commoners. Tensions between the dominating class and the

elites cause the commoners to seek out protection of their democratic

liberties. They invest all their power in their democratic demagogue,

who, in turn, becomes corrupted by the power and becomes a tyrant with a

small entourage of his supporters for protection and absolute control

of his people.

Reception and interpretation

Aristotle

Plato's most prominent pupil Aristotle, systematises many of Plato's analyses in his Politika, and criticizes the propositions of several political philosophers for the ideal city-state.

![[icon]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1c/Wiki_letter_w_cropped.svg/20px-Wiki_letter_w_cropped.svg.png) | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2021) |

Ancient Greece

It has been suggested that Isocrates parodies the Republic in his work Busiris by showing Callipolis' similarity to the Egyptian state founded by a king of that name.[20]

Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, wrote his version of an ideal society, Zeno's Republic, in opposition to Plato's Republic.[21] Zeno's Republic was controversial and was viewed with some embarrassment by some of the later Stoics due to its defenses of free love, incest, and cannibalism and due to its opposition to ordinary education and the building of temples, law-courts, and gymnasia.

Ancient Rome

Cicero

The English title of Plato's dialogue is derived from Cicero's De re publica,

written some three centuries later. Cicero's dialogue imitates Plato's

style and treats many of the same topics, and Cicero's main character Scipio Aemilianus expresses his esteem for Plato and Socrates.

Res publica is not an exact translation of Plato's Greek title politeia. Rather, politeia is a general term for the actual and potential forms of government for a polis

or city-state, and Plato attempts to survey all possible forms of the

state. Cicero's discussion is more parochial, focusing on the

improvement of the participants' own state, the Roman Republic in its final stages.

Tacitus

In antiquity, Plato's works were largely acclaimed, but a few commentators regarded them as too theoretical. Tacitus, commented on such works as The Republic and Aristotle's Politics in his Annals (IV, 33):

|

|

Nam cunctas nationes et urbes populus aut primores

aut singuli regunt: delecta ex iis (his) et consociata (constituta) rei

publicae forma laudari facilius quam evenire, vel si evenit, haud

diuturna esse potest.

|

|

Indeed, a nation or city is ruled by the people, or by an upper class, or by a monarch. A government system that is invented from a choice of these same components is sooner idealised than realised; and even if realised, there will be no future for it.

|

In this work, Tacitus undertakes the prosaic description and minute

analysis of how real states are governed, attempting to derive more

practical lessons about good versus bad governance than can be deduced

from speculations on ideal governments.

Augustine

In the pivotal era of Rome's move from its ancient polytheist religion to Christianity, Augustine wrote his magnum opus The City of God:

Again, the references to Plato, Aristotle and Cicero and their visions

of the ideal state were legion: Augustine equally described a model of

the "ideal city", in his case the eternal Jerusalem, using a visionary language not unlike that of the preceding philosophers.

Islam

Islamic philosophers were much more interested in Aristotle than Plato, but not having access to Aristotle's Politics, Ibn Rushd (Averroes) produced instead a commentary on

Plato's Republic. He advances an authoritarian ideal, following

Plato's paternalistic model. Absolute monarchy, led by a

philosopher-king, creates a justly ordered society. This requires

extensive use of coercion,[22] although persuasion is preferred and is possible if the young are properly raised.[23]

Rhetoric, not logic, is the appropriate road to truth for the common

man. Demonstrative knowledge via philosophy and logic requires special

study. Rhetoric aids religion in reaching the masses.[24]

Following Plato, Ibn Rushd accepts the principle of women's

equality. They should be educated and allowed to serve in the military;

the best among them might be tomorrow's philosophers or rulers.[25][26]

He also accepts Plato's illiberal measures such as the censorship of

literature. He uses examples from Arab history to illustrate just and

degenerate political orders.[27]

Hegel

Hegel respected Plato's theories of state and ethics much more than those of the early modern philosophers such as Locke, Hobbes and Rousseau, whose theories proceeded from a fictional "state of nature"

defined by humanity's "natural" needs, desires and freedom. For Hegel

this was a contradiction: since nature and the individual are

contradictory, the freedoms which define individuality as such are

latecomers on the stage of history. Therefore, these philosophers

unwittingly projected man as an individual in modern society onto a

primordial state of nature. Plato however had managed to grasp the

ideas specific to his time:

Plato is not the man to dabble in

abstract theories and principles; his truth-loving mind has recognized

and represented the truth of the world in which he lived, the truth of

the one spirit that lived in him as in Greece itself. No man can

overleap his time, the spirit of his time is his spirit also; but the

point at issue is, to recognize that spirit by its content.[28]

For Hegel, Plato's Republic is not an abstract theory or ideal which

is too good for the real nature of man, but rather is not ideal enough,

not good enough for the ideals already inherent or nascent in the

reality of his time; a time when Greece was entering decline. One such

nascent idea was about to crush the Greek way of life: modern

freedoms—or Christian freedoms in Hegel's view—such as the individual's

choice of his social class, or of what property to pursue, or which

career to follow. Such individual freedoms were excluded from Plato's

Republic:

Plato recognized and caught up the

true spirit of his times, and brought it forward in a more definite way,

in that he desired to make this new principle an impossibility in his

Republic.[29]

Greece being at a crossroads, Plato's new "constitution" in the Republic

was an attempt to preserve Greece: it was a reactionary reply to the

new freedoms of private property etc., that were eventually given legal

form through Rome. Accordingly, in ethical life, it was an attempt to

introduce a religion that elevated each individual not as an owner of

property, but as the possessor of an immortal soul.

20th century

Gadamer

In his 1934 Plato und die Dichter (Plato and the Poets), as well as several other works, Hans-Georg Gadamer describes the utopic city of the Republic as a heuristic utopia

that should not be pursued or even be used as an orientation-point for

political development. Rather, its purpose is said to be to show how

things would have to be connected, and how one thing would lead to

another—often with highly problematic results—if one would opt for

certain principles and carry them through rigorously. This

interpretation argues that large passages in Plato's writing are ironic, a line of thought initially pursued by Kierkegaard.

Popper

The city portrayed in the Republic struck some critics as harsh, rigid, and unfree; indeed, as totalitarian. Karl Popper gave a voice to that view in his 1945 book The Open Society and Its Enemies, where he singled out Plato's state as a dystopia. Popper distinguished Plato's ideas from those of Socrates, claiming that the former in his later years expressed none of the humanitarian and democratic tendencies of his teacher.[30]

Popper thought Plato's envisioned state totalitarian as it advocated a

government composed only of a distinct hereditary ruling class, with the

working class – who Popper argues Plato regards as "human cattle" –

given no role in decision making. He argues that Plato has no interest

in what are commonly regarded as the problems of justice – the

resolution of disputes between individuals – because Plato has redefined

justice as "keeping one's place".[31]

Voegelin

Eric Voegelin in Plato and Aristotle

(Baton Rouge, 1957), gave meaning to the concept of 'Just City in

Speech' (Books II-V). For instance, there is evidence in the dialogue

that Socrates himself would not be a member of his 'ideal' state. His life was almost solely dedicated to the private pursuit of knowledge.

More practically, Socrates suggests that members of the lower classes

could rise to the higher ruling class, and vice versa, if they had

'gold' in their veins—a version of the concept of social mobility. The exercise of power is built on the 'noble lie'

that all men are brothers, born of the earth, yet there is a clear

hierarchy and class divisions. There is a tripartite explanation of

human psychology that is extrapolated to the city, the relation among

peoples. There is no family among the guardians, another crude version of Max Weber's concept of bureaucracy

as the state non-private concern. Together with Leo Strauss, Voegelin

considered Popper's interpretation to be a gross misunderstanding not

only of the dialogue itself, but of the very nature and character of

Plato's entire philosophic enterprise.

Strauss and Bloom

Some of Plato's proposals have led theorists like Leo Strauss and Allan Bloom to ask readers to consider the possibility that Socrates

was creating not a blueprint for a real city, but a learning exercise

for the young men in the dialogue. There are many points in the

construction of the "Just City in Speech" that seem contradictory, which raise the possibility Socrates is employing irony to make the men in the dialogue question for themselves the ultimate value of the proposals. In turn, Plato has immortalized this 'learning exercise' in the Republic.

One of many examples is that Socrates calls the marriages of the ruling class 'sacred';

however, they last only one night and are the result of manipulating

and drugging couples into predetermined intercourse with the aim of

eugenically breeding guardian-warriors. Strauss and Bloom's

interpretations, however, involve more than just pointing out

inconsistencies; by calling attention to these issues they ask readers

to think more deeply about whether Plato is being ironic or genuine, for

neither Strauss nor Bloom present an unequivocal opinion, preferring to

raise philosophic doubt over interpretive fact.

Strauss's approach developed out of a belief that Plato wrote esoterically. The basic acceptance of the exoteric-esoteric

distinction revolves around whether Plato really wanted to see the

"Just City in Speech" of Books V-VI come to pass, or whether it is just

an allegory. Strauss never regarded this as the crucial issue of the dialogue. He argued against Karl Popper's literal view, citing Cicero's opinion that the Republic's true nature was to bring to light the nature of political things.[32]

In fact, Strauss undermines the justice found in the "Just City in

Speech" by implying the city is not natural, it is a man-made conceit

that abstracts away from the erotic needs of the body. The city founded

in the Republic "is rendered possible by the abstraction from eros".[33]

An argument that has been used against ascribing ironic intent to Plato is that Plato's Academy produced a number of tyrants

who seized political power and abandoned philosophy for ruling a city.

Despite being well-versed in Greek and having direct contact with Plato

himself, some of Plato's former students like Clearchus, tyrant of Heraclea; Chaeron, tyrant of Pellene; Erastus and Coriscus, tyrants of Skepsis; Hermias of Atarneus and Assos; and Calippus, tyrant of Syracuse

ruled people and did not impose anything like a philosopher-kingship.

However, it can be argued whether these men became "tyrants" through

studying in the Academy. Plato's school had an elite student body, some

of whom would by birth, and family expectation, end up in the seats of

power. Additionally, it is important to remember that it is by no means

obvious that these men were tyrants in the modern, totalitarian

sense of the concept. Finally, since very little is actually known

about what was taught at Plato's Academy, there is no small controversy

over whether it was even in the business of teaching politics at all.[34]

Fascism and Benito Mussolini

Mussolini utilized works of Plato, Georges Sorel, Nietzsche, and the economic ideas of Vilfredo Pareto, to develop fascism. Mussolini admired Plato's The Republic, which he often read for inspiration. The Republic

expounded a number of ideas that fascism promoted, such as rule by an

elite promoting the state as the ultimate end, opposition to democracy,

protecting the class system and promoting class collaboration, rejection

of egalitarianism, promoting the militarization of a nation by creating

a class of warriors, demanding that citizens perform civic duties in

the interest of the state, and utilizing state intervention in education

to promote the development of warriors and future rulers of the state.[36]

Plato was an idealist, focused on achieving justice and morality, while

Mussolini and fascism were realist, focused on achieving political

goals.[37]

Views on the city–soul analogy

Many critics, both ancient and modern (like Julia Annas),

have suggested that the dialogue's political discussion actually serves

as an analogy for the individual soul, in which there are also many

different "members" that can either conflict or else be integrated and

orchestrated under a just and productive "government." Among other

things, this analogical reading would solve the problem of certain

implausible statements Plato makes concerning an ideal political

republic. Norbert Blössner (2007)[38] argues that the Republic

is best understood as an analysis of the workings and moral improvement

of the individual soul with remarkable thoroughness and clarity. This

view, of course, does not preclude a legitimate reading of the Republic

as a political treatise (the work could operate at both levels). It

merely implies that it deserves more attention as a work on psychology

and moral philosophy than it has sometimes received.

Practicality

The above-mentioned views have in common that they view the Republic as a theoretical work, not as a set of guidelines for good governance.

However, Popper insists that the Republic, "was meant by its author not

so much as a theoretical treatise, but as a topical political

manifesto"[39] and Bertrand Russell argues that at least in intent, and all in all not so far from what was possible in ancient Greek city-states, the form of government portrayed in the Republic was meant as a practical one by Plato.[40]

21st century

One of Plato's recurring techniques in the Republic is to refine the concept of justice with reference to various examples of greater or lesser injustice. However, in The Concept of Injustice,[41] Eric Heinze

challenges the assumption that 'justice' and 'injustice' form a

mutually exclusive pair. Heinze argues that such an assumption traces

not from strict deductive logic, but from the arbitrary etymology of the

word 'injustice'. Heinze critiques what he calls 'classical' Western

justice theory for having perpetuated that logical error, which first

appears in Plato's Republic, but manifests throughout traditional political philosophy, in thinkers otherwise as different as Aristotle, Aquinas, Locke, Rousseau, Hegel and Marx.

In 2001, a survey of over 1,000 academics and students voted the Republic the greatest philosophical text ever written. Julian Baggini

argued that although the work "was wrong on almost every point, the

questions it raises and the methods it uses are essential to the western

tradition of philosophy. Without it we might not have philosophy as we

know it."[42]

According to a survey, The Republic is the most studied book in the top universities in the United States.[43][44]

Martin Luther King, Jr., nominated The Republic as the one book he would have taken to a deserted island, alongside the Bible.[45]

In fiction, Jo Walton's 2015 novel The Just City explored the consequences of establishing a city-state based on the Republic in practice.

Place in Plato's corpus

The Republic is generally placed in the middle period of Plato's dialogues—that is, it is believed to be written after the early period dialogues but before the late period

dialogues. However, the distinction of this group from the early

dialogues is not as clear as the distinction of the late dialogues from

all the others. Nonetheless, Ritter, Arnim, and Baron—with their

separate methodologies—all agreed that the Republic was well distinguished, along with Parmenides, Phaedrus and Theaetetus.[46]

However, the first book of the Republic, which shares many

features with earlier dialogues, is thought to have originally been

written as a separate work, and then the remaining books were conjoined

to it, perhaps with modifications to the original of the first book.[47]

Fragments

Several

Oxyrhynchus Papyri fragments were found to contain parts of the

Republic, and from other works such as

Phaedo, or the dialogue

Gorgias, written around 200–300 CE.

[48] Fragments of a different version of Plato's

Republic were discovered in 1945, part of the

Nag Hammadi library, written ca. 350 CE.

[49] These findings highlight the influence of Plato during those times in Egypt.