Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolingual speakers in the world's population. More than half of all Europeans claim to speak at least one language other than their mother tongue; but many read and write in one language. Multilingualism is advantageous for people wanting to participate in trade, globalization and cultural openness. Owing to the ease of access to information facilitated by the Internet, individuals' exposure to multiple languages has become increasingly possible. People who speak several languages are also called polyglots.

Multilingual speakers have acquired and maintained at least one language during childhood, the so-called first language (L1). The first language (sometimes also referred to as the mother tongue) is usually acquired without formal education, by mechanisms about which scholars disagree. Children acquiring two languages natively from these early years are called simultaneous bilinguals. It is common for young simultaneous bilinguals to be more proficient in one language than the other.

People who speak more than one language have been reported to be more adept at language learning compared to monolinguals.

Multilingualism in computing can be considered part of a continuum between internationalization and localization. Due to the status of English in computing, software development nearly always uses it (but not in the case of non-English-based programming languages). Some commercial software is initially available in an English version, and multilingual versions, if any, may be produced as alternative options based on the English original.

History

The first recorded use of the word multilingualism originated in the English language in the 1800s as a combination of multi (many) and lingual (pertaining to languages, with the word existing in the Middle Ages). The phenomenon however, is old as different languages themselves.

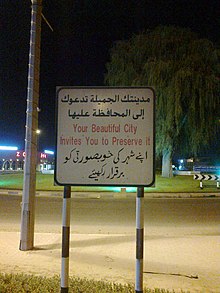

Together, like many different languages, modern-day multilingualism is still encountered by some people who speak the same language. Bilingual signs represent a multitude of languages in an evolutive variety of texts with each writing.

Definition

The definition of multilingualism is a subject of debate in the same way as that of language fluency. At one end of a sort of linguistic continuum, one may define multilingualism as complete competence in and mastery of more than one language. The speaker would presumably have complete knowledge and control over the languages and thus sound like a native speaker. At the opposite end of the spectrum would be people who know enough phrases to get around as a tourist using the alternate language. Since 1992, Vivian Cook has argued that most multilingual speakers fall somewhere between minimal and maximal definitions. Cook calls these people multi-competent.

In addition, there is no consistent definition of what constitutes a distinct language. For instance, scholars often disagree whether Scots is a language in its own right or merely a dialect of English. Furthermore, what is considered a language can change, often for purely political reasons. One example is the creation of Serbo-Croatian as a standard language on the basis of the Eastern Herzegovinian dialect to function as umbrella for numerous South Slavic dialects; after the breakup of Yugoslavia it was split into Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian and Montenegrin. Another example is that Ukrainian was dismissed as a Russian dialect by the Russian tsars to discourage national feelings. Many small independent nations' schoolchildren are today compelled to learn multiple languages because of international interactions. For example, in Finland, all children are required to learn at least three languages: the two national languages (Finnish and Swedish) and one foreign language (usually English). Many Finnish schoolchildren also study further languages, such as German or Russian.

In some large nations with multiple languages, such as India, schoolchildren may routinely learn multiple languages based on where they reside in the country.

In many countries, bilingualism occurs through international relations, which, with English being the global lingua franca, sometimes results in majority bilingualism even when the countries have just one domestic official language. This is occurring especially in Germanic regions such as Scandinavia, the Benelux and among Germanophones, but it is also expanding into some non-Germanic countries.

Acquisition

One view is that of the linguist Noam Chomsky in what he calls the human language acquisition device—a mechanism which enables a learner to recreate correctly the rules and certain other characteristics of language used by surrounding speakers. This device, according to Chomsky, wears out over time, and is not normally available by puberty, which he uses to explain the poor results some adolescents and adults have when learning aspects of a second language (L2).

If language learning is a cognitive process, rather than a language acquisition device, as the school led by Stephen Krashen suggests, there would only be relative, not categorical, differences between the two types of language learning.

Rod Ellis quotes research finding that the earlier children learn a second language, the better off they are, in terms of pronunciation. European schools generally offer secondary language classes for their students early on, due to the interconnectedness with neighbor countries with different languages. Most European students now study at least two foreign languages, a process strongly encouraged by the European Union.

Based on the research in Ann Fathman's The Relationship between age and second language productive ability, there is a difference in the rate of learning of English morphology, syntax and phonology based upon differences in age, but that the order of acquisition in second language learning does not change with age.

In second language class, students will commonly face difficulties in thinking in the target language because they are influenced by their native language and culture patterns. Robert B. Kaplan thinks that in second language classes, the foreign-student paper is out of focus because the foreign student is employing rhetoric and a sequence of thought which violate the expectations of the native reader. Foreign students who have mastered syntactic structures have still demonstrated an inability to compose adequate themes, term papers, theses, and dissertations. Robert B. Kaplan describes two key words that affect people when they learn a second language. Logic in the popular, rather than the logician's sense of the word, is the basis of rhetoric, evolved out of a culture; it is not universal. Rhetoric, then, is not universal either, but varies from culture to culture and even from time to time within a given culture. Language teachers know how to predict the differences between pronunciations or constructions in different languages, but they might be less clear about the differences between rhetoric, that is, in the way they use language to accomplish various purposes, particularly in writing.

People who learn multiple languages may also experience positive transfer – the process by which it becomes easier to learn additional languages if the grammar or vocabulary of the new language is similar to those of the languages already spoken. On the other hand, students may also experience negative transfer – interference from languages learned at an earlier stage of development while learning a new language later in life.

Receptive bilingualism

Receptive bilinguals are those who can understand a second language but who cannot speak it or whose abilities to speak it are inhibited by psychological barriers. Receptive bilingualism is frequently encountered among adult immigrants to the U.S. who do not speak English as a native language but who have children who do speak English natively, usually in part because those children's education has been conducted in English; while the immigrant parents can understand both their native language and English, they speak only their native language to their children. If their children are likewise receptively bilingual but productively English-monolingual, throughout the conversation the parents will speak their native language and the children will speak English. If their children are productively bilingual, however, those children may answer in the parents' native language, in English, or in a combination of both languages, varying their choice of language depending on factors such as the communication's content, context, and/or emotional intensity and the presence or absence of third-party speakers of one language or the other. The third alternative represents the phenomenon of "code-switching" in which the productively bilingual party to a communication switches languages in the course of that communication. Receptively bilingual persons, especially children, may rapidly achieve oral fluency by spending extended time in situations where they are required to speak the language that they theretofore understood only passively. Until both generations achieve oral fluency, not all definitions of bilingualism accurately characterize the family as a whole, but the linguistic differences between the family's generations often constitute little or no impairment to the family's functionality. Receptive bilingualism in one language as exhibited by a speaker of another language, or even as exhibited by most speakers of that language, is not the same as mutual intelligibility of languages; the latter is a property of a pair of languages, namely a consequence of objectively high lexical and grammatical similarities between the languages themselves (e.g., Norwegian and Swedish), whereas the former is a property of one or more persons and is determined by subjective or intersubjective factors such as the respective languages' prevalence in the life history (including family upbringing, educational setting, and ambient culture) of the person or persons.

Order of acquisition

In sequential bilingualism, learners receive literacy instruction in their native language until they acquire a "threshold" literacy proficiency. Some researchers use age three as the age when a child has basic communicative competence in their first language (Kessler, 1984). Children may go through a process of sequential acquisition if they migrate at a young age to a country where a different language is spoken, or if the child exclusively speaks his or her heritage language at home until he/she is immersed in a school setting where instruction is offered in a different language.

In simultaneous bilingualism, the native language and the community language are simultaneously taught. The advantage is literacy in two languages as the outcome. However, the teacher must be well-versed in both languages and also in techniques for teaching a second language.

The phases children go through during sequential acquisition are less linear than for simultaneous acquisition and can vary greatly among children. Sequential acquisition is a more complex and lengthier process, although there is no indication that non-language-delayed children end up less proficient than simultaneous bilinguals, so long as they receive adequate input in both languages.

A coordinate model posits that equal time should be spent in separate instruction of the native language and the community language. The native language class, however, focuses on basic literacy while the community language class focuses on listening and speaking skills. Being bilingual does not necessarily mean that one can speak, for example, English and French.

Outcomes

Research has found that the development of competence in the native language serves as a foundation of proficiency that can be transposed to the second language – the common underlying proficiency hypothesis. Cummins' work sought to overcome the perception propagated in the 1960s that learning two languages made for two competing aims. The belief was that the two languages were mutually exclusive and that learning a second required unlearning elements and dynamics of the first to accommodate the second. The evidence for this perspective relied on the fact that some errors in acquiring the second language were related to the rules of the first language.

Another new development that has influenced the linguistic argument for bilingual literacy is the length of time necessary to acquire the second language. While previously children were believed to have the ability to learn a language within a year, today researchers believe that within and across academic settings, the period is closer to five years.

An interesting outcome of studies during the early 1990s, however, confirmed that students who do complete bilingual instruction perform better academically. These students exhibit more cognitive elasticity including a better ability to analyze abstract visual patterns. Students who receive bidirectional bilingual instruction where equal proficiency in both languages is required perform at an even higher level. Examples of such programs include international and multi-national education schools.

In individuals

A multilingual person is someone who can communicate in more than one language actively (through speaking, writing, or signing). Multilingual people can speak any language they write in, but cannot necessarily write in any language they speak. More specifically, bilingual and trilingual people are those in comparable situations involving two or three languages, respectively. A multilingual person is generally referred to as a polyglot, a term that may also refer to people who learn multiple languages as a hobby. Multilingual speakers have acquired and maintained at least one language during childhood, the so-called first language (L1). The first language (sometimes also referred to as the mother tongue) is acquired without formal education, by mechanisms heavily disputed. Children acquiring two languages in this way are called simultaneous bilinguals. Even in the case of simultaneous bilinguals, one language usually dominates over the other.

In linguistics, first language acquisition is closely related to the concept of a "native speaker". According to a view widely held by linguists, a native speaker of a given language has in some respects a level of skill which a second (or subsequent) language learner cannot easily accomplish. Consequently, descriptive empirical studies of languages are usually carried out using only native speakers. This view is, however, slightly problematic, particularly as many non-native speakers demonstrably not only successfully engage with and in their non-native language societies, but in fact may become culturally and even linguistically important contributors (as, for example, writers, politicians, media personalities and performing artists) in their non-native language. In recent years, linguistic research has focused attention on the use of widely known world languages, such as English, as a lingua franca or a shared common language of professional and commercial communities. In lingua franca situations, most speakers of the common language are functionally multilingual.

The reverse phenomenon, where people who know more than one language end up losing command of some or all of their additional languages, is called language attrition. It has been documented that, under certain conditions, individuals may lose their L1 language proficiency completely, after switching to the exclusive use of another language, and effectively "become native" in a language that was once secondary after the L1 undergoes total attrition.

This is most commonly seen among immigrant communities and has been the subject of substantial academic study. The most important factor in spontaneous, total L1 loss appears to be age; in the absence of neurological dysfunction or injury, only young children typically are at risk of forgetting their native language and switching to a new one. Once they pass an age that seems to correlate closely with the critical period, around the age of 12, total loss of a native language is not typical, although it is still possible for speakers to experience diminished expressive capacity if the language is never practiced.

Cognitive ability

People who use more than one language have been reported to be more adept at language learning compared to monolinguals. Individuals who are highly proficient in two or more languages have been reported to have enhanced executive functions, such as inhibitory control or cognitive flexibility, or even have reduced-risk for dementia. More recently, however, this claim has come under strong criticism with repeated failures to replicate. One possible reason for this discrepancy is that bilingualism is rich and diverse; bilingualism can take different forms according to the context and geographic location in which it is studied. Yet, many prior studies do not reliably quantify samples of bilinguals under investigation. An emerging perspective is that studies on bilingual and multilingual cognitive abilities need to account for validated and granular quantifications of language experience in order to identify boundary conditions of possible cognitive effects.

Auditory ability

Bilingual and multilingual individuals are shown to have superior auditory processing abilities compared to monolingual individuals. Several investigations have compared auditory processing abilities of monolingual and bilingual individuals using tasks such as gap detection, temporal ordering, pitch pattern recognition etc. In general, results of studies have reported superior performance among bilingual and multilingual individuals. Further, among bilingual individuals, the level of proficiency in the second language was also reported to have an influence on the auditory processing abilities.

Economic benefits

Bilinguals might have important labor market advantages over monolingual individuals as bilingual people can carry out duties that monolinguals cannot, such as interacting with customers who only speak a minority language. A study in Switzerland has found that multilingualism is positively correlated with an individual's salary, the productivity of firms, and the gross domestic production (GDP); the authors state that Switzerland's GDP is augmented by 10% by multilingualism. A study in the United States by Agirdag found that bilingualism has substantial economic benefits as bilingual persons were found to have around $3,000 per year more salary than monolinguals.

Psychology

A study in 2012 has shown that using a foreign language reduces decision-making biases. It was surmised that the framing effect disappeared when choices are presented in a second language. As human reasoning is shaped by two distinct modes of thought: one that is systematic, analytical and cognition-intensive, and another that is fast, unconscious and emotionally charged, it was believed that a second language provides a useful cognitive distance from automatic processes, promoting analytical thought and reducing unthinking, emotional reaction. Therefore, those who speak two languages have better critical thinking and decision-making skills. A study published a year later found that switching into a second language seems to exempt bilinguals from the social norms and constraints such as political correctness. In 2014, another study has shown that people using a foreign language are more likely to make utilitarian decisions when faced with a moral dilemma, as in the trolley problem. The utilitarian option was chosen more often in the fat man case when presented in a foreign language. However, there was no difference in the switch track case. It was surmised that a foreign language lacks the emotional impact of one's native language.

Personality

Because it is difficult or impossible to master many of the high-level semantic aspects of a language (including but not limited to its idioms and eponyms) without first understanding the culture and history of the region in which that language evolved, as a practical matter an in-depth familiarity with multiple cultures is a prerequisite for high-level multilingualism. This knowledge of cultures individually and comparatively can form an important part of both what one considers one's identity to be and what others consider that identity to be. Some studies have found that groups of multilingual individuals get higher average scores on tests for certain personality traits such as cultural empathy, open-mindedness and social initiative. The idea of linguistic relativity, which claims that the language people speak influences the way they see the world, can be interpreted to mean that individuals who speak multiple languages have a broader, more diverse view of the world, even when speaking only one language at a time. Some bilinguals feel that their personality changes depending on which language they are speaking; thus multilingualism is said to create multiple personalities. Xiao-lei Wang states in her book Growing up with Three Languages: Birth to Eleven: "Languages used by speakers with one or more than one language are used not just to represent a unitary self, but to enact different kinds of selves, and different linguistic contexts create different kinds of self-expression and experiences for the same person." However, there has been little rigorous research done on this topic and it is difficult to define "personality" in this context. François Grosjean wrote: "What is seen as a change in personality is most probably simply a shift in attitudes and behaviors that correspond to a shift in situation or context, independent of language." However, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which states that a language shapes our vision of the world, may suggest that a language learned by a grown-up may have much fewer emotional connotations and therefore allow a more serene discussion than a language learned by a child and to that respect more or less bound to a child's perception of the world. A 2013 study found that rather than an emotion-based explanation, switching into the second language seems to exempt bilinguals from the social norms and constraints such as political correctness.

Hyperpolyglots

While many polyglots know up to six languages, the number drops off sharply past this point. People who speak many more than this—Michael Erard suggests eleven or more—are sometimes classed as hyperpolyglots. Giuseppe Caspar Mezzofanti, for example, was an Italian priest reputed to have spoken anywhere from 30 to 72 languages. The causes of advanced language aptitude are still under research; one theory suggests that a spike in a baby's testosterone levels while in the uterus can increase brain asymmetry, which may relate to music and language ability, among other effects.

While the term "savant" generally refers to an individual with a natural and/or innate talent for a particular field, people diagnosed with savant syndrome are typically individuals with significant mental disabilities who demonstrate profound and prodigious capacities and/or abilities far in excess of what would be considered normal, occasionally including the capacity for languages. The condition is associated with an increased memory capacity, which would aid in the storage and retrieval of knowledge of a language. In 1991, for example, Neil Smith and Ianthi-Maria Tsimpli described Christopher, a man with non-verbal IQ scores between 40 and 70, who learned sixteen languages. Christopher was born in 1962 and approximately six months after his birth was diagnosed with brain damage. Despite being institutionalized because he was unable to take care of himself, Christopher had a verbal IQ of 89, was able to speak English with no impairment, and could learn subsequent languages with apparent ease. This facility with language and communication is considered unusual among savants.

Terms

- monolingual, monoglot - 1 language spoken

- bilingual, diglot - 2 languages spoken

- trilingual, triglot - 3 languages spoken

- quadrilingual, tetraglot - 4 languages spoken

- quinquelingual, pentaglot - 5 languages spoken

- sexalingual, hexaglot - 6 languages spoken

- septilingual or septalingual, heptaglot - 7 languages spoken

- octolingual or octalingual, octoglot - 8 languages spoken

- novelingual or nonalingual, enneaglot - 9 languages spoken

- decalingual, decaglot - 10 languages spoken

- undecalingual, hendecaglot - 11 languages spoken

- duodecalingual, dodecaglot - 12 languages spoken

It is important to note that terms past trilingual are rarely used. People who speak four or more languages are generally just referred to as multilingual.

Neuroscience

In communities

Widespread multilingualism is one form of language contact. Multilingualism was common in the past: in early times, when most people were members of small language communities, it was necessary to know two or more languages for trade or any other dealings outside one's town or village, and this holds good today in places of high linguistic diversity such as Sub-Saharan Africa and India. Linguist Ekkehard Wolff estimates that 50% of the population of Africa is multilingual.

In multilingual societies, not all speakers need to be multilingual. Some states can have multilingual policies and recognize several official languages, such as Canada (English and French). In some states, particular languages may be associated with particular regions in the state (e.g., Canada) or with particular ethnicities (e.g., Malaysia and Singapore). When all speakers are multilingual, linguists classify the community according to the functional distribution of the languages involved:

- Diglossia: if there is a structural-functional distribution of the languages involved, the society is termed 'diglossic'. Typical diglossic areas are those areas in Europe where a regional language is used in informal, usually oral, contexts, while the state language is used in more formal situations. Frisia (with Frisian and German or Dutch) and Lusatia (with Sorbian and German) are well-known examples. Some writers limit diglossia to situations where the languages are closely related and could be considered dialects of each other. This can also be observed in Scotland where, in formal situations, English is used. However, in informal situations in many areas, Scots is the preferred language of choice. A similar phenomenon is also observed in Arabic-speaking regions. The effects of diglossia could be seen in the difference between written Arabic (Modern Standard Arabic) and colloquial Arabic. However, as time goes, the Arabic language somewhere between the two has been created what some have deemed "Middle Arabic" or "Common Arabic". Because of this diversification of the language, the concept of spectroglossia has been suggested.

- Ambilingualism: a region is called ambilingual if this functional distribution is not observed. In a typical ambilingual area it is nearly impossible to predict which language will be used in a given setting. True ambilingualism is rare. Ambilingual tendencies can be found in small states with multiple heritages like Luxembourg, which has a combined Franco-Germanic heritage, or Malaysia and Singapore, which fuses the cultures of Malays, China, and India or communities with high rates of deafness like Martha's Vineyard where historically most inhabitants spoke both MVSL and English or in southern Israel where locals speak both Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language and either Arabic or Hebrew. Ambilingualism also can manifest in specific regions of larger states that have both a dominant state language (be it de jure or de facto) and a protected minority language that is limited in terms of the distribution of speakers within the country. This tendency is especially pronounced when, even though the local language is widely spoken, there is a reasonable assumption that all citizens speak the predominant state tongue (e.g., English in Quebec vs. all of Canada; Spanish in Catalonia vs. all of Spain). This phenomenon can also occur in border regions with many cross-border contacts.

- Bipart-lingualism: if more than one language can be heard in a small area, but the large majority of speakers are monolinguals, who have little contact with speakers from neighboring ethnic groups, an area is called 'bipart-lingual'. An example of this is the Balkans.

N.B. the terms given above all refer to situations describing only two languages. In cases of an unspecified number of languages, the terms polyglossia, omnilingualism, and multipart-lingualism are more appropriate.

Taxell’s paradox refers to the notion that monolingual solutions are essential to the realization of functional bilingualism, with multilingual solutions ultimately leading to monolingualism. The theory is based on the observation of the Swedish language in Finland in environments such as schools is subordinated to the majority language Finnish for practical and social reasons, despite the positive characteristics associated with mutual language learning.

Interaction between speakers of different languages

Whenever two people meet, negotiations take place. If they want to express solidarity and sympathy, they tend to seek common features in their behavior. If speakers wish to express distance towards or even dislike of the person they are speaking to, the reverse is true, and differences are sought. This mechanism also extends to language, as described in the Communication Accommodation Theory.

Some multilinguals use code-switching, which involves swapping between languages. In many cases, code-switching allows speakers to participate in more than one cultural group or environment. Code-switching may also function as a strategy where proficiency is lacking. Such strategies are common if the vocabulary of one of the languages is not very elaborated for certain fields, or if the speakers have not developed proficiency in certain lexical domains, as in the case of immigrant languages.

This code-switching appears in many forms. If a speaker has a positive attitude towards both languages and towards code-switching, many switches can be found, even within the same sentence. If however, the speaker is reluctant to use code-switching, as in the case of a lack of proficiency, he might knowingly or unknowingly try to camouflage his attempt by converting elements of one language into elements of the other language through calquing. This results in speakers using words like courrier noir (literally mail that is black) in French, instead of the proper word for blackmail, chantage.

Sometimes a pidgin language may develop. A pidgin language is a fusion of two languages that is mutually understandable for both speakers. Some pidgin languages develop into real languages (such as Papiamento in Curaçao or Singlish in Singapore) while others remain as slangs or jargons (such as Helsinki slang, which is more or less mutually intelligible both in Finnish and Swedish). In other cases, prolonged influence of languages on each other may have the effect of changing one or both to the point where it may be considered that a new language is born. For example, many linguists believe that the Occitan language and the Catalan language were formed because of a population speaking a single Occitano-Romance language was divided into political spheres of influence of France and Spain, respectively. Yiddish is a complex blend of Middle High German with Hebrew and borrowings from Slavic languages.

Bilingual interaction can even take place without the speaker switching. In certain areas, it is not uncommon for speakers to use a different language within the same conversation. This phenomenon is found, amongst other places, in Scandinavia. Most speakers of Swedish, Norwegian and Danish can communicate with each other speaking their respective languages, while few can speak both (people used to these situations often adjust their language, avoiding words that are not found in the other language or that can be misunderstood). Using different languages is usually called non-convergent discourse, a term introduced by the Dutch linguist Reitze Jonkman. To a certain extent, this situation also exists between Dutch and Afrikaans, although everyday contact is fairly rare because of the distance between the two respective communities. Another example is the former state of Czechoslovakia, where two closely related and mutually intelligible languages (Czech and Slovak) were in common use. Most Czechs and Slovaks understand both languages, although they would use only one of them (their respective mother tongue) when speaking. For example, in Czechoslovakia, it was common to hear two people talking on television each speaking a different language without any difficulty understanding each other. This bilinguality still exists nowadays, although it has started to deteriorate after Czechoslovakia split up.

A sign uses Arabic, Tifinagh and French Latin alphabets

Computing

With emerging markets and expanding international cooperation, business users expect to be able to use software and applications in their own language. Multilingualisation (or "m17n", where "17" stands for 17 omitted letters) of computer systems can be considered part of a continuum between internationalization and localization:

- A localized system has been adapted or converted for a particular locale (other than the one it was originally developed for), including the language of the user interface, input, and display, and features such as time/date display and currency; but each instance of the system only supports a single locale.

- Multilingualised software supports multiple languages for display and input simultaneously, but generally has a single user interface language. Support for other locale features like time, date, number and currency formats may vary as the system tends towards full internationalization. Generally, a multilingual system is intended for use in a specific locale, whilst allowing for multilingual content.

- An internationalized system is equipped for use in a range of locales, allowing for the co-existence of several languages and character sets in user interfaces and displays. In particular, a system may not be considered internationalized in the fullest sense unless the interface language is selectable by the user at runtime.

Translating the user interface is usually part of the software localization process, which also includes adaptations such as units and date conversion. Many software applications are available in several languages, ranging from a handful (the most spoken languages) to dozens for the most popular applications (such as office suites, web browsers, etc.). Due to the status of English in computing, software development nearly always uses it (but see also Non-English-based programming languages), so almost all commercial software is initially available in an English version, and multilingual versions, if any, may be produced as alternative options based on the English original.

The Multilingual App Toolkit (MAT) was first released in concert with the release of Windows 8 as a way to provide developers a set of free tooling that enabled adding languages to their apps with just a few clicks, in large part due to the integration of a free, unlimited license to both the Microsoft Translator machine translation service and the Microsoft Language Platform service, along with platform extensibility to enable anyone to add translation services into MAT. Microsoft engineers and inventors of MAT, Jan A. Nelson, and Camerum Lerum have continued to drive development of the tools, working with third parties and standards bodies to assure broad availability of multilingual app development is provided. With the release of Windows 10, MAT is now delivering support for cross-platform development for Windows Universal Apps as well as IOS and Android.

Internet

English-speaking countries

According to Hewitt (2008) entrepreneurs in London from Poland, China or Turkey use English mainly for communication with customers, suppliers, and banks, but their native languages for work tasks and social purposes. Even in English-speaking countries immigrants are still able to use their mother tongue in the workplace thanks to other immigrants from the same place. Kovacs (2004) describes this phenomenon in Australia with Finnish immigrants in the construction industry who spoke Finnish during working hours. Although foreign languages may be used in the workplace, English is still a key working skill. Mainstream society justifies the divided job market, arguing that getting a low-paying job is the best that newcomers can achieve considering their limited language skills.

Asia

With companies going international they are now focusing more and more on the English level of their employees. Especially in South Korea since the 1990s, companies are using different English language testing to evaluate job applicants, and the criteria in those tests are constantly upgrading the level for good English. In India, it is even possible to receive training to acquire an English accent, as the number of outsourced call centers in India has soared in the past decades. Meanwhile, Japan ranks 53rd out of 100 countries in 2019 EF English Proficiency Index, amid calls for this to improve in time for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

Within multiracial countries such as Malaysia and Singapore, it is not unusual for one to speak two or more languages, albeit with varying degrees of fluency. Some are proficient in several Chinese dialects, given the linguistic diversity of the ethnic Chinese community in both countries.

Africa

Not only in multinational companies is English an important skill, but also in the engineering industry, in the chemical, electrical and aeronautical fields. A study directed by Hill and van Zyl (2002) shows that in South Africa young black engineers used English most often for communication and documentation. However, Afrikaans and other local languages were also used to explain particular concepts to workers in order to ensure understanding and cooperation.

Europe

In Europe, as the domestic market is generally quite restricted, international trade is a norm. Languages that are used in multiple countries include:

- German in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, and Belgium

- French in France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Monaco, Andorra and Switzerland

- English in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Malta.

- Swedish in Sweden and Finland.

- Italian in Italy and Switzerland.

English is a commonly taught second language at schools, so it is also the most common choice for two speakers, whose native languages are different. However, some languages are so close to each other that it is generally more common when meeting to use their mother tongue rather than English. These language groups include:

- Danish, Swedish and Norwegian

- Czech and Slovak: during Czechoslovak times, these were considered to be two different dialects of a common Czechoslovak language.

- Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian and Montenegrin: standardized in the 19th century and throughout existence of Yugoslavia, Croatian and Serbian were considered as Western and Eastern variants of a common, Serbo-Croatian language. After the breakup of Yugoslavia, each successor state proclaimed and codified its own official language. In sociolinguistics, however, these are still considered standardized varieties of one pluricentric language, all based on Shtokavian dialect, with the biggest distinction being between the Ekavian and Ijekavian pronunciation. Cyrillic and Latin writing scripts are official in Bosnian, Montenegrin and Serbian, while Latin is exclusively official in Croatian.

In multilingual countries such as Belgium (Dutch, French, and German), Finland (Finnish and Swedish), Switzerland (German, French, Italian and Romansh), Luxembourg (Luxembourgish, French and German) or Spain (Spanish, Catalan, Basque and Galician), it is common to see employees mastering two or even three of those languages.

Many minor Russian ethnic groups, such as Tatars, Bashkirs and others, are also multilingual. Moreover, with the beginning of compulsory study of the Tatar language in Tatarstan, there has been an increase in its level of knowledge of the Russian-speaking population of the republic.

Continued global diversity has led to an increasingly multilingual workforce. Europe has become an excellent model to observe this newly diversified labor culture. The expansion of the European Union with its open labor market has provided opportunities both for well-trained professionals and unskilled workers to move to new countries to seek employment. Political changes and turmoil have also led to migration and the creation of new and more complex multilingual workplaces. In most wealthy and secure countries, immigrants are found mostly in low paid jobs but also, increasingly, in high-status positions.

Music

It is extremely common for music to be written in whatever the contemporary lingua franca is. If a song is not written in a common tongue, then it is usually written in whatever is the predominant language in the musician's country of origin, or in another widely recognized language, such as English, German, Spanish, or French.

The bilingual song cycles "there..." and "Sing, Poetry" on the 2011 contemporary classical album Troika consist of musical settings of Russian poems with their English self-translation by Joseph Brodsky and Vladimir Nabokov, respectively.

Songs with lyrics in multiple languages are known as macaronic verse.

Literature

Fiction

Multilingual stories, essays, and novels are often written by immigrants and second generation American authors. Chicana author Gloria E. Anzaldúa, a major figure in the fields Third World Feminism, Postcolonial Feminism, and Latino philosophy explained the author's existential sense of obligation to write multilingual literature. An often quoted passage, from her collection of stories and essays entitled Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, states:

"Until I am free to write bilingually and to switch codes without having always to translate, while I still have to speak English or Spanish when I would rather speak Spanglish, and as long as I have to accommodate the English speakers rather than having them accommodate me, my tongue will be illegitimate. I will no longer be made to feel ashamed of existing. I will have my voice: Indian, Spanish, white. I will have my serpent’s tongue – my woman’s voice, my sexual voice, my poet’s voice. I will overcome the tradition of silence".

Multilingual novels by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie display phrases in Igbo with translations, as in her early works Purple Hibiscus and Half of a Yellow Sun. However, in her later novel Americanah, the author does not offer translations of non-English passages. The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros is an example of Chicano literature has untranslated, but italicized, Spanish words and phrases throughout the text.

American novelists who use foreign languages (outside of their own cultural heritage) for literary effect, include Cormac McCarthy who uses untranslated Spanish and Spanglish in his fiction.

Poetry

Multilingual poetry is prevalent in US Latino literature where code-switching and translanguaging between English, Spanish, and Spanglish is common within a single poem or throughout a book of poems. Latino poetry is also written in Portuguese and can include phrases in Nahuatl, Mayan, Huichol, Arawakan, and other indigenous languages related to the Latino experience. Contemporary multilingual poets include Giannina Braschi, Ana Castillo, Sandra Cisneros, and Guillermo Gómez-Peña

![{\displaystyle \sigma ^{\mu \nu }=i\left[\gamma ^{\mu },\gamma ^{\nu }\right]/2}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a4b313fd46f9dca789d6003848ca4cf297146aaf)