From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_war_crimes

War crimes are defined as acts which violate the laws and customs of war established by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, or acts that are grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I and Additional Protocol II. The Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 extends the protection of civilians and prisoners of war during military occupation,

even in the case where there is no armed resistance, for the period of

one year after the end of hostilities, although the occupying power

should be bound to several provisions of the convention as long as "such

Power exercises the functions of government in such territory."

List of war crimes in chronological order

Philippine–American War

General

Jacob H. Smith's infamous order "

Kill Everyone Over Ten" was the caption in the

New York Journal

cartoon on May 5, 1902. The Old Glory draped an American shield on

which a vulture replaced the bald eagle. The caption at the bottom

proclaimed, "

Criminals Because They Were Born Ten Years Before We Took the Philippines".

Following the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898, Spain ceded the Captaincy General of the Philippines to the United States as part of the peace settlement. This triggered a conflict between the United States Armed Forces and revolutionary First Philippine Republic under President Emilio Aguinaldo, and the Moro fighters.

During the March across Samar, Brigadier General Jacob H. Smith ordered Major Littleton Waller, commanding officer of a battalion of 315 U.S. Marines

assigned to Smith's forces in Samar, to kill all persons "who are

capable of bearing arms in actual hostilities" over the age of ten years

old.

The widespread massacre of Filipino civilians followed as American

columns marched across the island. All food and trade to Samar were cut

off, and the widespread destruction of homes, crops, and draft animals

occurred, with the intention of starving the Filipino revolutionaries

and the civilian populace into submission. Smith used his troops in

sweeps of the interior to search for guerrilla bands and in attempts to

capture Philippine General Vicente Lukbán,

but he did nothing to prevent contact between the guerrillas and the

population. Waller stated in a report that over an eleven-day period his

men burned 255 dwellings, shot 13 carabaos, and killed 39 people.

An exhaustive research made by a British writer in the 1990s put the

figure at about 2,500 dead; Filipino historians believe it to be around

50,000. As a consequence of his order in Samar, Smith became known as "Howling Wilderness Smith". In May 1902, Smith was convicted at his court-martial in the United States for the order he gave to Waller in Samar.

The aftermath of the Moro Crater battle or massacre

On March 5, 1906, the First Battle of Bud Dajo, also known as the Moro Crater Massacre, began when an assault force consisting of soldiers from the 6th Infantry, the 19th Infantry, the 4th Cavalry, the 28th Artillery Battery, the U.S. naval gunboat Pampanga, and men from the Philippine Constabulary opened fire with mountain guns against Moro fortifications in the Bud Dajo crater which was populated by 800 to 1,000 Tausug villagers. Additionally, a machine gun was used to sweep the crest of the mountain.

At the battle's conclusion by March 8, only six Moros had survived,

with 99% having been killed. Moro men in the crater possessed melee

weapons, and while fighting was limited to ground action on Jolo, use of

naval gunfire contributed significantly to the overwhelming firepower

brought to bear against the Moros.

One account claims that the Moros, armed with knives and spears,

refused to surrender and held their positions. Some of the defenders

rushed the Americans and were cut down by artillery fire. The Americans

charged the surviving Moros with fixed bayonets, and the Moros fought

back with their kalis, barung, improvised grenades made with black powder and seashells.

Despite the inconsistencies among various accounts of the battle,

one in which all occupants of Bud Dajo were gunned down, another in

which defenders resisted in fierce hand-to-hand combat, all accounts

agree that few, if any, Moros survived, and the description of it being a "battle" became a matter of dispute. The author Vic Hurley wrote, "By no stretch of the imagination could Bud Dajo be termed a 'battle'". Mark Twain strongly condemned the incident in several articles he published,

and commented: "In what way was it a battle? It has no resemblance to a

battle. We cleaned up our four days' work and made it complete by

butchering these helpless people."

Major Hugh Scott, the province's District Governor said that those who

fled to the crater "declared they had no intention of fighting, ran up

there only in fright, and had some crops planted and desired to

cultivate them."

In response to criticism, Wood's explanation of the high number

of women and children killed stated that the women of Bud Dajo dressed

as men and joined in the combat, and that the men used children as

living shields. Hagedorn supports this explanation, by presenting an account of Lieutenant Gordon Johnston, who was allegedly severely wounded by a female warrior. A second explanation was given by the Governor-General of the Philippines, Henry Clay Ide, who reported that the women and children were collateral damage, having been killed during the artillery barrages.

These conflicting explanations of the high number of women and child

casualties brought accusations of a cover-up, further adding fire to the

criticism. According to Joshua Gedacht, Wood's and Ide's explanation is at odds with the use of the machine-gun

that was placed to the edge of the crater to fire upon its occupants;

Gedacht states that the high number of non-combatants killed can be

explained as the result of indiscriminate machine-gun fire.

Banana Wars

First and Second Caco Wars

An October 1921 article from the

Merced Sun-Star discussing killings of Haitians by U.S. commanded Haitian gendarmerie

During the First (1915) and Second (1918-1920) Caco Wars which were both waged during the United States occupation of Haiti (1915–1934), human rights abuses were committed against the native Haitian population. Overall, the United States Marine Corps and the Haitian gendarmerie

killed several thousands of Haitian civilians during the rebellions

between 1915 and 1920, though the exact death toll is unknown.

During Senate hearings in 1921, the commandant of the Marine Corps

reported that, in the 20 months of active unrest, 2,250 Haitians had

been killed. However, in a report to the Secretary of the Navy, he

reported the death toll as being 3,250. Haitian historian Roger Gaillard, estimated that in total, including rebel combatants and civilians, at least 15,000 Haitians were killed during the occupation. According to Paul Farmer, the higher estimates are not accepted by most historians outside Haiti.

Mass killings of civilians were allegedly committed by United States Marines and their subordinates in the Haitian gendarmerie. According to Haitian historian Roger Gaillard, such killings involved rape, lynchings, summary executions, burning villages and deaths by burning. Internal documents of the United States Army

justified the killing of women and children, describing them as

"auxiliaries" of rebels. A private memorandum of the Secretary of the

Navy criticized “indiscriminate killings against natives”. American

officers who were responsible for acts of violence were given Haitian Creole

names such as "Linx" for Commandant Freeman Lang and "Ouiliyanm" for

Lieutenant Lee Williams. According to American journalist H.J. Seligman,

Marines would practice "bumping off Gooks", describing the shooting of

civilians in a manner which was similar to killing for sport.

During the Second Caco War of 1918–1919, many Caco prisoners were summarily executed by Marines and the gendarmerie on orders from their superiors. On June 4, 1916, Marines executed caco General Mizrael Codio and ten others after they were captured in Fonds-Verrettes. In Hinche

in January 1919, Captain Ernest Lavoie of the gendarmerie, a former

United States Marine, allegedly ordered the killing of nineteen caco

rebels according to American officers, though no charges were ever filed

against him due to the fact that no physical evidence of the killing

was ever presented.

The torture of Haitian rebels and the torture of Haitians who

were suspected of rebelling against the United States was a common

practice among the occupying Marines. Some of the methods of torture

included the use of water cure, hanging prisoners by their genitals and ceps, which involved pushing both sides of the tibia with the butts of two guns.

World War II

Pacific theater

On January 26, 1943, the submarine USS Wahoo fired on survivors in lifeboats from the Imperial Japanese Army transport ship Buyo Maru. Vice Admiral Charles A. Lockwood asserted that the survivors were Japanese soldiers who had turned machine-gun and rifle fire on the Wahoo after it surfaced, and that such resistance was common in submarine warfare.

According to the submarine's executive officer, the fire was intended

to force the Japanese soldiers to abandon their boats and none of them

were deliberately targeted. Historian Clay Blair stated that the submarine's crew fired first and the shipwrecked survivors returned fire with handguns. The survivors were later determined to have included Allied POWs of the British Indian Army's 2nd Battalion, 16th Punjab Regiment, who were guarded by Japanese Army Forces from the 26th Field Ordnance Depot. Of 1,126 men originally aboard Buyo Maru, 195 Indians and 87 Japanese died, some killed during the torpedoing of the ship and some killed by the shootings afterwards.

During and after the Battle of the Bismarck Sea (March 3–5, 1943), U.S. PT boats

and Allied aircraft attacked Japanese rescue vessels as well as

approximately 1,000 survivors from eight sunken Japanese troop transport

ships.

The stated justification was that the Japanese personnel were close to

their military destination and would be promptly returned to service in

the battle. Many of the Allied aircrew accepted the attacks as necessary, while others were sickened.

American servicemen in the Pacific War deliberately killed Japanese soldiers who had surrendered, according to Richard Aldrich, a professor of history at the University of Nottingham. Aldrich published a study of diaries kept by United States and Australian soldiers, wherein it was stated that they sometimes massacred prisoners of war. According to John Dower, in "many instances ... Japanese who did become prisoners were killed on the spot or en route to prison compounds." According to Professor Aldrich, it was common practice for U.S. troops not to take prisoners. His analysis is supported by British historian Niall Ferguson,

who also says that, in 1943, "a secret [U.S.] intelligence report noted

that only the promise of ice cream and three days leave would ...

induce American troops not to kill surrendering Japanese."

Ferguson states that such practices played a role in the ratio of

Japanese prisoners to dead being 1:100 in late 1944. That same year,

efforts were taken by Allied high commanders to suppress "take no

prisoners" attitudes

among their personnel (because it hampered intelligence gathering), and

to encourage Japanese soldiers to surrender. Ferguson adds that

measures by Allied commanders to improve the ratio of Japanese prisoners

to Japanese dead resulted in it reaching 1:7, by mid-1945.

Nevertheless, "taking no prisoners" was still "standard practice" among

U.S. troops at the Battle of Okinawa, in April–June 1945.

Ferguson also suggests that "it was not only the fear of disciplinary

action or of dishonor that deterred German and Japanese soldiers from

surrendering. More important for most soldiers was the perception that

prisoners would be killed by the enemy anyway, and so one might as well

fight on."

Ulrich Straus, a U.S. Japanologist,

suggests that Allied troops on the front line intensely hated Japanese

military personnel and were "not easily persuaded" to take or protect

prisoners, because they believed that Allied personnel who surrendered

got "no mercy" from the Japanese. Allied troops were told that Japanese soldiers were inclined to feign surrender in order to make surprise attacks, a practice which was outlawed by the Hague Convention of 1907.

Therefore, according to Straus, "Senior officers opposed the taking of

prisoners on the grounds that it needlessly exposed American troops to

risks ..." When prisoners were taken at the Guadalcanal campaign,

Army interrogator Captain Burden noted that many times POWs were shot

during transport because "it was too much bother to take [them] in".

U.S. historian James J. Weingartner attributes the very low number of Japanese in U.S. prisoner of war compounds

to two important factors, namely (1) a Japanese reluctance to

surrender, and (2) a widespread American "conviction that the Japanese

were 'animals' or 'subhuman' and unworthy of the normal treatment

accorded to prisoners of war."

The latter reason is supported by Ferguson, who says that "Allied

troops often saw the Japanese in the same way that Germans regarded

Russians—as Untermenschen (i.e., "subhuman")."

Mutilation of Japanese war dead

American sailor with the skull of a Japanese soldier during

World War IIIn the Pacific theater, American servicemen engaged in human trophy collecting.

The phenomenon of "trophy-taking" was widespread enough that discussion

of it featured prominently in magazines and newspapers. Franklin Roosevelt himself was reportedly given a gift of a letter-opener made of a Japanese soldier's arm by U.S. Representative Francis E. Walter in 1944, which Roosevelt later ordered to be returned, calling for its proper burial.

The news was also widely reported to the Japanese public, where the

Americans were portrayed as "deranged, primitive, racist and inhuman".

This, compounded by a previous Life

magazine picture of a young woman with a skull trophy, was reprinted in

the Japanese media and presented as a symbol of American barbarism,

causing national shock and outrage.

War rape

U.S. military personnel raped Okinawan women during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945.

Based on several years of research, Okinawan historian Oshiro

Masayasu (former director of the Okinawa Prefectural Historical

Archives) writes:

Soon after the U.S. Marines landed, all the women of a village on Motobu Peninsula

fell into the hands of American soldiers. At the time, there were only

women, children, and old people in the village, as all the young men had

been mobilized for the war. Soon after landing, the Marines "mopped up"

the entire village, but found no signs of Japanese forces. Taking

advantage of the situation, they started 'hunting for women' in broad

daylight, and women who were hiding in the village or nearby air raid

shelters were dragged out one after another.

According to interviews carried out by The New York Times

and published by them in 2000, several elderly people from an Okinawan

village confessed that after the United States had won the Battle of

Okinawa, three armed Marines kept coming to the village every week to

force the villagers to gather all the local women, who were then carried

off into the hills and raped. The article goes deeper into the matter

and claims that the villagers' tale—true or not—is part of a "dark,

long-kept secret" the unraveling of which "refocused attention on what

historians say is one of the most widely ignored crimes of the war":

"the widespread rape of Okinawan women by American servicemen."

Although Japanese reports of rape were largely ignored at the time, one

academic estimated that as many as 10,000 Okinawan women may have been

raped. It has been claimed that the rape was so prevalent that most

Okinawans over age 65 around the year 2000 either knew or had heard of a

woman who was raped in the aftermath of the war.

Professor of East Asian Studies and expert on Okinawa, Steve Rabson,

said: "I have read many accounts of such rapes in Okinawan newspapers

and books, but few people know about them or are willing to talk about

them."

He notes that plenty of old local books, diaries, articles and other

documents refer to rapes by American soldiers of various races and

backgrounds. An explanation given for why the US military has no record

of any rapes is that few Okinawan women reported abuse, mostly out of

fear and embarrassment. According to an Okinawan police spokesman: "Victimized women feel too ashamed to make it public." Those who did report them are believed by historians to have been ignored by the U.S. military police.

Many people wondered why it never came to light after the inevitable

American-Japanese babies the many women must have given birth to. In

interviews, historians and Okinawan elders said that some of those

Okinawan women who were raped and did not commit suicide did give birth

to biracial children, but that many of them were immediately killed or

left behind out of shame, disgust or fearful trauma. More often,

however, rape victims underwent crude abortions with the help of village

midwives. A large scale effort to determine the possible extent of

these crimes has never been conducted. Over five decades after the war

had ended, in the late-1990s, the women who were believed to have been

raped still overwhelmingly refused to give public statements, instead

speaking through relatives and a number of historians and scholars.

There is substantial evidence that the U.S. had at least some

knowledge of what was going on. Samuel Saxton, a retired captain,

explained that the American veterans and witnesses may have

intentionally kept the rape a secret, largely out of shame: "It would be

unfair for the public to get the impression that we were all a bunch of

rapists after we worked so hard to serve our country." Military officials formally denied the mass rapes, and all surviving related veterans refused request for interviews from The New York Times.

Masaie Ishihara, a sociology professor, supports this: "There is a lot

of historical amnesia out there, many people don't want to acknowledge

what really happened." Author George Feifer noted in his book Tennozan: The Battle of Okinawa and the Atomic Bomb,

that by 1946 there had been fewer than 10 reported cases of rape in

Okinawa. He explained it was "partly because of shame and disgrace,

partly because Americans were victors and occupiers. In all there were

probably thousands of incidents, but the victims' silence kept rape

another dirty secret of the campaign."

Some other authors have noted that Japanese civilians "were often

surprised at the comparatively humane treatment they received from the

American enemy." According to Islands of Discontent: Okinawan Responses to Japanese and American Power by Mark Selden, the Americans "did not pursue a policy of torture, rape, and murder of civilians as Japanese military officials had warned."

According to numerous academics, there were also 1,336 reported rapes during the first 10 days of the occupation of Kanagawa prefecture

after the Japanese surrender, however, Brian Walsh states that this

claim originated from a misreading of crime figures and that the

Japanese Government had actually recorded 1,326 criminal incidents of

all types involving American forces, of which an unspecified number were

rapes.

European theater

Soldiers

of the U.S. Seventh Army guard SS prisoners in a coal yard at Dachau

concentration camp during its liberation. April 29, 1945 (U.S. Army

photograph)

In the Laconia incident, U.S. aircraft attacked Germans rescuing survivors from the sinking British troopship in the Atlantic Ocean. Pilots of a United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) B-24 Liberator bomber, despite knowing the U-boat's location, intentions, and the presence of British seamen, killed dozens of Laconia's survivors with bombs and strafing attacks, forcing U-156 to cast its remaining survivors into the sea and crash dive to avoid being destroyed.

During the Allied invasion of Sicily,

some massacres of civilians by US troops were reported, including the

Vittoria one, where 12 Italians died (including a 17-year-old boy), and in Piano Stella, where a group of peasants was murdered.

The "Canicattì massacre"

involved the killing of Italian civilians by Lieutenant Colonel George

Herbert McCaffrey; a confidential inquiry was made, but McCaffrey was

never charged with any offense relating to the massacre. He died in

1954. This fact remained virtually unknown in the U.S. until 2005, when

Joseph S. Salemi of New York University, whose father witnessed it, reported it.

In the "Biscari massacre", which consisted of two instances of mass murder, U.S. troops of the 45th Infantry Division killed 73 prisoners of war, mostly Italian.

According to an article in Der Spiegel by Klaus Wiegrefe, many personal memoirs of Allied soldiers have been wilfully ignored by historians until now because they were at odds with the "greatest generation" mythology surrounding World War II. However, this has recently started to change, with books such as The Day of Battle, by Rick Atkinson, in which he describes Allied war crimes in Italy, and D-Day: The Battle for Normandy, by Antony Beevor. Beevor's latest work suggests that Allied war crimes in Normandy were much more extensive "than was previously realized".

Historian Peter Lieb has found that many U.S. and Canadian units were ordered not to take enemy prisoners during the D-Day landings in Normandy.

If this view is correct, it may explain the fate of 64 German prisoners

(out of the 130 captured) who did not make it to the POW collecting

point on Omaha Beach on the day of the landings.

Near the French village of Audouville-la-Hubert, 30 Wehrmacht prisoners were massacred by U.S. paratroopers.

George S. Pattons' war diary entry from January 4, 1945. Regarding the

Chenogne massacre on January 1, 1945 Patton noted: "Also murdered 50 odd German med [sic]. I hope we can conceal this."

In the aftermath of the 1944 Malmedy massacre, in which 80 American POWs were murdered by their German captors, a written order from the headquarters of the 328th U.S. Army Infantry Regiment, dated 21 December 1944, stated: "No SS troops or paratroopers will be taken prisoner but [rather they] will be shot on sight."

Major-General Raymond Hufft (U.S. Army) gave instructions to his troops

not to take prisoners when they crossed the Rhine in 1945. "After the

war, when he reflected on the war crimes he authorized, he admitted, 'if

the Germans had won, I would have been on trial at Nuremberg instead of

them.'" Stephen Ambrose

related: "I've interviewed well over 1000 combat veterans. Only one of

them said he shot a prisoner ... Perhaps as many as one-third of the

veterans...however, related incidents in which they saw other GIs

shooting unarmed German prisoners who had their hands up."

In the "Chenogne massacre" during the Battle of the Bulge on January 1, 1945, members of the 11th Armored Division killed an estimated 80 German prisoners of war, which were assembled in a field and shot with machine guns.

The events were covered up at the time, and none of the perpetrators

were ever punished. Postwar historians believe the killings were carried

out on verbal orders by senior commanders that "no prisoners were to be taken". General George S. Patton confirmed in his diary that the Americans "...also murdered 50 odd German med [sic]. I hope we can conceal this".

"Operation Teardrop" involved eight surviving captured crewmen from the sunken German submarine U-546 being tortured by U.S. military personnel. Historian Philip K. Lundeberg has written that the beating and torture of U-546's

survivors was a singular atrocity motivated by the interrogators' need

to quickly get information on what the U.S. believed were potential

missile attacks on the contiguous United States by German submarines.

Among American WWII veterans who admitted to having committed war crimes was former Mafia hitman Frank Sheeran. In interviews with his biographer Charles Brandt, Sheeran recalled his war service with the Thunderbird Division

as the time when he first developed a callousness to the taking of

human life. By his own admission, Sheeran participated in numerous

massacres and summary executions of German POWs, acts which violated the

Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the 1929 Geneva Convention on POWs. In his interviews with Brandt, Sheeran divided such massacres into four different categories.

- 1. Revenge killings in the heat of battle. Sheeran told Brandt that, when a German Army

soldier had just killed his close friends and then tried to surrender,

he would often "send him to hell, too." He described often witnessing

similar behavior by fellow GIs.

- 2. Orders from unit commanders during a mission. When describing his

first murder for organized crime, Sheeran recalled: "It was just like

when an officer would tell you to take a couple of German prisoners back

behind the line and for you to 'hurry back'. You did what you had to

do."

- 3. The Dachau massacre and other reprisal killings of concentration camp guards and trustee inmates.

- 4. Calculated attempts to dehumanize and degrade German POWs. While Sheeran's unit was climbing the Harz Mountains, they came upon a Wehrmacht

mule train carrying food and drink up the mountainside. The female

cooks were first allowed to leave unmolested, then Sheeran and his

fellow GIs "ate what we wanted and soiled the rest with our waste." Then

the Wehrmacht mule drivers were given shovels and ordered to "dig their

own shallow graves." Sheeran later joked that they did so without

complaint, likely hoping that he and his buddies would change their

minds. But the mule drivers were shot and buried in the holes they had

dug. Sheeran explained that by then, "I had no hesitation in doing what I

had to do."

Rape

Secret wartime files made public only in 2006 reveal that American

GIs committed 400 sexual offenses in Europe, including 126 rapes in

England, between 1942 and 1945.

A study by Robert J. Lilly estimates that a total of 14,000 civilian

women in England, France and Germany were raped by American GIs during

World War II.

He estimates that there were around 3,500 rapes by American servicemen

in France between June 1944 and the end of the war. Historian William

Hitchcock states that sexual violence against women in liberated France was common.

Korean War

No Gun Ri

The No Gun Ri massacre refers to an incident of mass killing of an undetermined number of South Korean refugees by U.S. soldiers of the 7th Cavalry Regiment (and in a U.S. air attack) between 26 and 29 July 1950 at a railroad bridge near the village of Nogeun-ri, 100 miles (160 km) southeast of Seoul. In 2005, the South Korean

government certified the names of 163 dead or missing (mostly women,

children, and old men) and 55 wounded. It said that many other victims'

names were not reported. The South Korean government-funded No Gun Ri Peace Foundation estimated in 2011 that 250–300 were killed. Over the years survivors' estimates of the dead have ranged from 300 to 500. This episode early in the Korean War gained widespread attention when the Associated Press (AP) published a series of articles in 1999 that subsequently won a Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting.

Vietnam War

American soldiers surrounded by beheaded corpses of Vietcong fighters

RJ Rummel estimated that American forces killed around 5,500 people in democide between 1960 and 1972 in the Vietnam War, from a range of between 4,000 and 10,000. Benjamin Valentino estimates 110,000–310,000 deaths as a "possible case" of "counter-guerrilla mass killings" by U.S. and South Vietnamese forces during the war.

During the war, 95 U.S. Army personnel and 27 U.S. Marine Corps

personnel were convicted by court-martial of the murder or manslaughter

of Vietnamese.

U.S. forces also established numerous free-fire zones as a tactic to prevent Viet Cong fighters from sheltering in South Vietnamese villages.

Such practice, which involved the assumption that any individual

appearing in the designated zones was an enemy combatant that could be

freely targeted by weapons, is regarded by journalist Lewis M. Simons as

"a severe violation of the laws of war". Nick Turse, in his 2013 book, Kill Anything that Moves, argues that a relentless drive toward higher body counts,

a widespread use of free-fire zones, rules of engagement where

civilians who ran from soldiers or helicopters could be viewed as Viet

Cong and a widespread disdain for Vietnamese civilians led to massive

civilian casualties and endemic war crimes inflicted by U.S. troops.

My Lai Massacre

Dead bodies outside a burning dwelling in My Lai

The My Lai massacre was the mass murder of 347 to 504 unarmed citizens in South Vietnam, almost entirely civilians, most of them women and children, conducted by U.S. soldiers from the Company C of the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade of the 23rd (American) Infantry Division,

on 16 March 1968. Some of the victims were raped, beaten, tortured, or

maimed, and some of the bodies were found mutilated. The massacre took

place in the hamlets of Mỹ Lai and My Khe of Sơn Mỹ village during the Vietnam War. Of the 26 U.S. soldiers initially charged with criminal offenses or war crimes for actions at My Lai, only William Calley

was convicted. Initially sentenced to life in prison, Calley had his

sentence reduced to ten years, then was released after only three and a

half years under house arrest.

The incident prompted widespread outrage around the world, and reduced

U.S. domestic support for the Vietnam War. Three American Servicemen (Hugh Thompson, Jr., Glenn Andreotta, and Lawrence Colburn),

who made an effort to halt the massacre and protect the wounded, were

sharply criticized by U.S. Congressmen, and received hate mail, death

threats, and mutilated animals on their doorsteps. Thirty years after the event their efforts were honored.

Following the massacre a Pentagon task force called the Vietnam War Crimes Working Group

(VWCWG) investigated alleged atrocities by U.S. troops against South

Vietnamese civilians and created a formerly secret archive of some 9,000

pages (the Vietnam War Crimes Working Group Files housed by the National Archives and Records Administration)

documenting 320 alleged incidents from 1967 to 1971 including 7

massacres (not including the My Lai Massacre) in which at least 137

civilians died; 78 additional attacks targeting noncombatants in which

at least 57 were killed, 56 wounded and 15 sexually assaulted; and 141

incidents of U.S. soldiers torturing civilian detainees or prisoners of

war. 203 U.S. personnel were charged with crimes, 57 were

court-martialed and 23 were convicted. The VWCWG also investigated over

500 additional alleged atrocities but could not verify them.

Operation Speedy Express

Operation Speedy Express was a controversial military operation aimed at pacifying large parts of the Mekong delta

from December 1968 to May 1969. The U.S. Army claimed 10,899 PAVN/VC

were killed in the operation, while the US Army Inspector General

estimated that there were 5,000 to 7,000 civilian deaths from the

operation. Robert Kaylor of United Press International

alleged that according to American pacification advisers in the Mekong

Delta during the operation the division had indulged in the "wanton

killing" of civilians through the "indiscriminate use of mass

firepower."

Phoenix Program

Two United States soldiers and one

South Vietnamese soldier waterboard a captured North Vietnamese prisoner of war near

Da Nang, 1968.

The Phoenix Program was coordinated by the CIA, involving South

Vietnamese, US and other allied security forces, with the aim

identifying and destroying the Viet Cong (VC) through infiltration, torture, capture, counter-terrorism, interrogation, and assassination.

The program was heavily criticized, with critics labeling it a

"civilian assassination program" and criticizing the operation's use of

torture.

Tiger Force

Tiger Force was the name of a long-range reconnaissance patrol unit of the 1st Battalion (Airborne), 327th Infantry, 1st Brigade (Separate), 101st Airborne Division, which fought from November 1965 to November 1967.

The unit gained notoriety after investigations during the course of the

war and decades afterwards revealed extensive war crimes against

civilians, which numbered into the hundreds. They were accused of

routine torture, execution of prisoners and the intentional killing of

civilians. US army investigators concluded that many of the alleged war

crimes took place.

Other incidents

On 12 August 1965 Lcpl McGhee of Company M, 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines, walked through Marine lines at Chu Lai Base Area

toward a nearby village. In answer to a Marine sentry's shouted

question, he responded that he was going after a VC. Two Marines were

dispatched to retrieve McGhee and as they approached the village they

heard a shot and a woman's scream and then saw McGhee walking toward

them from the village. McGhee said he had just killed a VC and other VC

were following him. At trial Vietnamese prosecution witnesses testified

that McGhee had kicked through the wall of the hut where their family

slept. He seized a 14-year-old girl and pulled her toward the door. When

her father interceded, McGhee shot and killed him. Once outside the

house the girl escaped McGhee with the help of her grandmother. McGhee

was found guilty of unpremeditated murder and sentenced him to

confinement at hard labor for ten years. On appeal this was reduced to 7

years and he actually served 6 years and 1 month.

On 23 September 1966, a nine-man ambush patrol from the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines,

left Hill 22, northwest of Chu Lai. Private First Class John D. Potter,

Jr. took effective command of the patrol. They entered the hamlet of

Xuan Ngoc (2) and seized Dao Quang Thinh, whom they accused of being a

Viet Cong, and dragged him from his hut. While they beat him, other

patrol members forced his wife, Bui Thi Huong, from their hut and four

of them raped her. A few minutes later three other patrol members shot

Dao Quang Thinh, Bui, their child, Bui's sister-in-law, and her sister

in- law's child. Bui Thi Huong survived to testify at the

courts-martial. The company commander suspicious of the reported "enemy

contact" sent Second Lieutenant Stephen J. Talty, to return to the scene

with the patrol. Once there, Talty realized what had happened and

attempted to cover up the incident. A wounded child was discovered alive

and Potter bludgeoned it to death with his rifle. Potter was convicted

of premeditated murder and rape, and sentenced to confinement at hard

labor for life, but was released in February 1978, having served 12

years and 1 month.

Hospitalman John R. Bretag testified against Potter and was sentenced

to 6 month's confinement for rape. PFC James H. Boyd, Jr., pleaded

guilty to murder and was sentenced to 4 years confinement at hard labor.

Sergeant Ronald L. Vogel was convicted for murder of one of the

children and rape and was sentenced to 50 years confinement at hard

labor, which was reduced on appeal to 10 years, of which he served 9

years. Two patrol members were acquitted of major charges, but were

convicted of assault with intent to commit rape and sentenced to 6

months' confinement. Lt Talty was found guilty of making a false report

and dismissed from the Marine Corps, but this was overturned on appeal.

PFC Charles W. Keenan was convicted of murder by firing at

point-blank range into an unarmed, elderly Vietnamese woman, and an

unarmed Vietnamese man. His life sentence was reduced to 25 years

confinement. Upon appeal, the conviction for the woman's murder was

dismissed and confinement was reduced to five years. Later clemency

action further reduced his confinement to 2 years and 9 months. Corporal

Stanley J. Luczko, was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter and

sentenced to confinement for three years

From 31 January to 1 February 1967, 145 civilians were purported

to have been killed by Company H, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, during the

Thuy Bo incident. Marine accounts record 101 Viet Cong and 22 civilians killed during a 2-day battle.

On 5 May 1968, Lcpl Denzil R. Allen led a six-man ambush patrol

from the 1st Battalion, 27th Marines near Huế. They stopped and

interrogated two unarmed Vietnamese men who Allen and Private Martin R.

Alvarez then executed. After an attack on their base that night the unit

sent out a patrol who brought back three Vietnamese men. Allen,

Alvarez, Lance Corporals John D. Belknap, James A. Maushart, PFC Robert

J. Vickers, and two others then formed a firing squad and executed two

of the Vietnamese. The third captive was taken into a building where

Allen, Belknap, and Anthony Licciardo, Jr., hanged him, when the rope

broke Allen cut the man's throat, killing him. Allen pleaded guilty to

five counts of unpremeditated murder and was sentenced to confinement at

hard labor for life reduced to 20 years in exchange for the guilty

plea. Allen's confinement was reduced to 7 years and he was paroled

after having served only 2 years and 11 months confinement. Maushart

pleaded guilty to one count of unpremeditated murder and was sentenced

to 2 years confinement of which he served 1 year and 8 months. Belknap

and Licciardo each pleaded guilty to single murders and were sentenced

to 2 years confinement. Belknap served 15 months while Licciardo served

his full sentence. Alvarez was found to lack mental responsibility and

found not guilty. Vickers was found guilty of two counts of

unpremeditated murder, but his convictions were overturned on review.

On the morning of 1 March 1969 an eight-man Marine ambush was

discovered by three Vietnamese girls, aged about 13, 17, and 19, and a

Vietnamese boy, about 11. The four shouted their discovery to those

being observed by the ambush. Seized by the Marines, the four were

bound, gagged, and led away by Corporal Ronald J. Reese and Lance

Corporal Stephen D. Crider. Minutes later, the 4 children were seen,

apparently dead, in a small bunker. The Marines tossed a fragmentation

grenade into the bunker, which then collapsed the damaged structure atop

the bodies. Reese and Crider were each convicted of four counts of

murder and sentenced to confinement at hard labor for life. On appeal

both sentences were reduced to 3 years confinement.

On February 19, 1970, during the Son Thang massacre, 16 unarmed women and children were killed in the Son Thang Hamlet by Company B, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines.

One person was sentenced to life in prison, another sentenced to 5

years, but both sentences were reduced to less than a year. with those

killed reported as enemy combatant.

On 2 June 1971, Brigadier General John W. Donaldson

was charged with the murder of six Vietnamese civilians but was

acquitted due to lack of evidence. In 13 separate incidents Donaldson

was alleged to have flown over civilian areas shooting at civilians. He

was the first U.S. general charged with war crimes since General Jacob H. Smith in 1902 and the highest ranking American to be accused of war crimes during the Vietnam War. The charges were dropped due to lack of evidence.

War on Terror

In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks in 2001, the U.S. Government

adopted several new measures in the classification and treatment of

prisoners captured in the War on Terror, including applying the status

of unlawful combatant to some prisoners, conducting extraordinary renditions and using torture ("enhanced interrogation techniques"). Human Rights Watch and others described the measures as being illegal under the Geneva Conventions. The torture of detainees was extensively detailed in the Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture.

Command responsibility

A presidential memorandum of February 7, 2002, authorized U.S. interrogators of prisoners captured during the War in Afghanistan

to deny the prisoners basic protections required by the Geneva

Conventions, and thus according to Jordan J. Paust, professor of law and

formerly a member of the faculty of the Judge Advocate General's School, "necessarily authorized and ordered violations of the Geneva Conventions, which are war crimes." Based on the president's memorandum, U.S. personnel carried out cruel and inhumane treatment on captured enemy fighters,

which necessarily means that the president's memorandum was a plan to

violate the Geneva Convention, and such a plan constitutes a war crime

under the Geneva Conventions, according to Professor Paust.

U.S. Attorney General Alberto Gonzales

and others have argued that detainees should be considered "unlawful

combatants" and as such not be protected by the Geneva Conventions in

multiple memoranda regarding these perceived legal gray areas.

Gonzales' statement that denying coverage under the Geneva

Conventions "substantially reduces the threat of domestic criminal

prosecution under the War Crimes Act"

suggests, to some authors, an awareness by those involved in crafting

policies in this area that U.S. officials are involved in acts that

could be seen to be war crimes. The U.S. Supreme Court challenged the premise on which this argument is based in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, in which it ruled that Common Article Three of the Geneva Conventions applies to detainees in Guantanamo Bay and that the military tribunals used to try these suspects were in violation of U.S. and international law.

Human Rights Watch claimed in 2005 that the principle of "command responsibility" could make high-ranking officials within the Bush administration guilty of the numerous war crimes committed during the War on Terror, either with their knowledge or by persons under their control. On April 14, 2006, Human Rights Watch said that Secretary Donald Rumsfeld could be criminally liable for his alleged involvement in the abuse of Mohammed al-Qahtani. On November 14, 2006, invoking universal jurisdiction,

legal proceedings were started in Germany—for their alleged involvement

of prisoner abuse—against Donald Rumsfeld, Alberto Gonzales, John Yoo, George Tenet and others.

The Military Commissions Act of 2006 is seen by some as an amnesty law for crimes committed in the War on Terror by retroactively rewriting the War Crimes Act and by abolishing habeas corpus, effectively making it impossible for detainees to challenge crimes committed against them.

Luis Moreno-Ocampo told The Sunday Telegraph in 2007 that he was willing to start an inquiry by the International Criminal Court (ICC), and possibly a trial, for war crimes committed in Iraq involving British Prime Minister Tony Blair and American President George W. Bush. Though under the Rome Statute,

the ICC has no jurisdiction over Bush, since the U.S. is not a State

Party to the relevant treaty—unless Bush were accused of crimes inside a

State Party, or the UN Security Council

(where the U.S. has a veto) requested an investigation. However, Blair

does fall under ICC jurisdiction as Britain is a State Party.

Shortly before the end of President Bush's second term in 2009,

news media in countries other than the U.S. began publishing the views

of those who believe that under the United Nations Convention Against Torture, the U.S. is obligated to hold those responsible for prisoner abuse to account under criminal law. One proponent of this view was the United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Professor Manfred Nowak) who, on January 20, 2009, remarked on German television that former president George W. Bush had lost his head of state immunity and under international law the U.S. would now be mandated to start criminal proceedings against all those involved in these violations of the UN Convention Against Torture. Law professor Dietmar Herz

explained Nowak's comments by opining that under U.S. and international

law former President Bush is criminally responsible for adopting

torture as an interrogation tool.

War in Afghanistan (2001–2021)

In 2005, The New York Times obtained a 2,000-page United States Army investigatory report concerning the homicides of two unarmed civilian Afghan prisoners by U.S. military personnel in December 2002 at the Bagram Theater Internment Facility (also Bagram Collection Point or B.C.P.) in Bagram, Afghanistan and general treatment of prisoners. The two prisoners, Habibullah and Dilawar, were repeatedly chained to the ceiling and beaten, resulting in their deaths. Military coroners ruled that both the prisoners' deaths were homicides. Autopsies

revealed severe trauma to both prisoners' legs, describing the trauma

as comparable to being run over by a bus. Seven soldiers were charged in

2005.

The Maywand District murders involved the killing of three Afghan civilians by a group of soldiers during the period June 2009 to June 2010. The soldiers referred to their group as "Kill Team" and were members the 2nd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment, and 5th Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division. They were based at FOB Ramrod in Maiwand, from Kandahar Province of Afghanistan. During the summer of 2010, the military charged five members of the platoon with the murders of three Afghan civilians in Kandahar Province and collecting their body parts as trophies.

The Kandahar massacre was a mass murder that occurred in the early hours of 11 March 2012, when Staff Sergeant Robert Bales killed 16 Afghan civilians and wounded six others in the Panjwayi District of Kandahar Province, Afghanistan.

Nine of the victims were children, and eleven of the dead were from the

same family. Bales was taken into custody later that morning when he

confessed to authorities that he had committed the murders.

First Lieutenant Clint Lorance was an infantry platoon leader in the 4th Brigade Combat Team of the 82nd Airborne Division.

In 2012, Lorance was charged with two counts of unpremeditated murder

after he ordered his soldiers to open fire on three Afghan men who were

on a motorcycle. He was found guilty by a court-martial in 2013 and sentenced to 20 years in prison (later reduced to 19 years by the reviewing commanding general). He was confined in the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas for six years. Lorance was eventually pardoned by President Donald Trump on November 15, 2019.

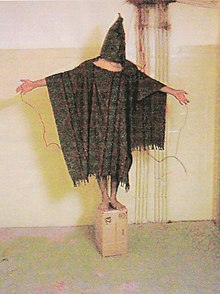

Iraq War

During the early stages of the Iraq War, a group of soldiers committed a series of human rights violations including physical and sexual abuse against detainees in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. The abuses came to public attention with the publication of photographs of the abuse by CBS News

in April 2004. The incidents caused shock and outrage, receiving

widespread condemnation within the United States and internationally. The Department of Defense charged eleven soldiers with dereliction of duty, maltreatment, aggravated assault and battery. Between May 2004 and April 2006, these soldiers were court-martialed, convicted, sentenced to military prison, and dishonorably discharged from service. Two soldiers, found to have perpetrated many of the worst offenses at the prison, Charles Graner and Lynndie England, were subject to more severe charges and received harsher sentences. Graner was convicted of assault, battery,

conspiracy, maltreatment of detainees, committing indecent acts and

dereliction of duty; he was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment and loss

of rank, pay and benefits. England was convicted of conspiracy, maltreating detainees and committing an indecent act and sentenced to three years in prison. Brigadier General Janis Karpinski,

the commanding officer of all detention facilities in Iraq, was

reprimanded and demoted to the rank of colonel.. Several more military

personnel who were accused of perpetrating or authorizing the measures,

including many of higher rank, were not prosecuted. In 2004, President George W. Bush and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld apologized for the Abu Ghraib abuses.

On March 12, 2006, a 14-year-old Iraqi girl named Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabi was raped and subsequently murdered

along her 34-year-old mother Fakhriyah Taha Muhasen, 45-year-old father

Qassim Hamza Raheem, and 6-year-old sister Hadeel Qassim Hamza

al-Janabi. The killings took place in the family home in Yusufiyah, a village to the west of the town of Al-Mahmudiyah, Iraq. Five soldiers from the 502nd Infantry Regiment were charged with rape and murder: Paul E. Cortez, James P. Barker, Jesse V. Spielman, Bryan L. Howard, and Steven Dale Green. Green was discharged from the U.S. Army for mental instability

before the crimes were known by his command, whereas Cortez, Barker,

Spielman and Howard were tried by a military court martial, convicted,

and sentenced to decades in prison. Green was tried and convicted in a United States civilian court and was sentenced to life in prison, but committed suicide in prison in 2014.

John E. Hatley was a first sergeant who was prosecuted by the Army in 2008 for murdering four Iraqi detainees near Baghdad, Iraq in 2006. He was convicted in 2009 and sentenced to life in prison at the Fort Leavenworth Disciplinary Barracks. He was released on parole in October 2020.

The Hamdania incident involved the alleged kidnapping and subsequent murder of an Iraqi man by United States Marines on April 26, 2006, in Al Hamdania, a small village west of Baghdad near Abu Ghraib. An investigation by the Naval Criminal Investigative Service resulted in charges of murder, kidnapping, housebreaking, larceny, Obstruction of Justice and conspiracy associated with the alleged coverup of the incident.

The Haditha massacre occurred on November 19, 2005, in Haditha, Iraq. After Lance Cpl. Miguel Terrazas (20 years old) was killed by a roadside improvised explosive device, Staff Sergeant Frank Wuterich led Marines from the 3rd battalion into Haditha.

24 Iraqi women and children were fatally shot. Wuterich acknowledged in

military court that he gave his men the order to "shoot first, ask

questions later"

after the roadside bomb explosion. Wuterich told military judge Lt.

Col. David Jones "I never fired my weapon at any women or children that

day." On January 24, 2012, Frank Wuterich was given a sentence of 90

days in prison along with a reduction in rank and pay. The day prior,

Wuterich pled guilty to one count of negligent dereliction of duty.

No other marine that was involved that day was sentenced to any jail

time. For the massacre, the Marine Corps paid $38,000 total to the

families of 15 of the dead civilians.