The working poor are working people whose incomes fall below a given poverty line due to low-income jobs and low familial household income. These are people who spend at least 27 weeks in a year working or looking for employment, but remain under the poverty threshold.

In the US, the official measurement of the working poor is controversial. Many social scientists argue that the official measurements used do not provide a comprehensive overview of the number of working poor. One recent study proposed over 100 ways to measure this and came up with a figure that ranged between 2% and 19% of the total US population.

There is also controversy surrounding ways that the working poor can be helped. Arguments range from increasing welfare to the poor on one end of the spectrum to encouraging the poor to achieve greater self-sufficiency on the other end, with most arguing varying degrees of both.

Measurement

Absolute

According to the US Department of Labor, the working poor "are persons who spent at least 27 weeks [in the past year] in the labor force (that is, working or looking for work), but whose incomes fell below the official poverty level." In other words, if someone spent more than half of the past year in the labor force without earning more than the official poverty threshold, the US Department of Labor would classify them as "working poor". (Note: The official poverty threshold, which is set by the US Census Bureau, varies depending on the size of a family and the age of the family members.) As of 2018, the poverty threshold for a family of four people is $25,701 and for a single person $12,784. The official poverty threshold is calculated by using the Consumer Price Index for goods, multiplying the cost of a minimum food diet in 1963 by three, a family's gross income (before tax), and the number of family members. In 2017, there were 6.9 million individuals defined as working poor. Because there has been, and still is, debate on how accurate using this metric is, the US Census Bureau began publishing a Supplemental Poverty Measure in 2011. The main difference using this metric is that a person's poverty status is determined after subtracting taxes, food, clothing, shelter, utilities, childcare and work-related expenses, and including government benefits and people living in the home that do not fit the "family" definition (such as an unmarried couple, or dependent foster children). Using the SPM, the poverty rate overall increases, particularly the rate of the working poor. In 2018, the official rate was 5.1% vs the SPM's measure of 7.2%.

Relative

In Europe and other non-US, high-income countries, poverty and working poverty are defined in relative terms. A relative measure of poverty is based on a country's income distribution rather than an absolute amount of money. Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union, classifies a household as poor if its income is less than 60 percent of the country's median household income. According to Eurostat, a relative measure of poverty is appropriate because "minimal acceptable standards usually differ between societies according to their general level of prosperity: someone regarded as poor in a rich developed country might be regarded as rich in a poor developing country."

According to the latest data the UK's working poor rate is 10%, with the median income being £507 per week in 2018.

A profile of the working poor in the US

According to a 2017 report from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics 4.5% of all people working or looking for work for at least 27 weeks in the previous year had incomes below the poverty level. 10.9% of those were employed part-time, and 2.9% were employed full-time. The occupations that have the highest poverty rate are agricultural jobs, such as farming, service sector jobs, such as fast food or retail, and the construction industry, at 9.7%, 9.0% and 7.1% respectively. The largest ethnicity groups of the working poor are African-American and Hispanics or Latinos, both at 7.9%, with whites at 3.9% and Asian at 2.9%. Women are far more likely than men to be working and in poverty, 10% vs 5.6%. While the majority of the working poor have a high school diploma or less, 5% have some college education, 3.2% have an associate degree, and 1.5% have a bachelor's degree or higher. Families with children are four times as likely as a single person to live in poverty, with families headed by single women making up 16% of all working poor families.

Prevalence and trends

In 2018, according to the US Census Bureau's official definition of poverty, 38.1 million US citizens were below the poverty line (11.8% of the population). However this number includes children under 18 years of age, elders over 65, and people with disabilities who cannot work. The poverty rate of people between the ages of 18 to 64 was 10.7%, or 21.1 million people. Of these, nearly half, 5.1%, were working at least part-time.

Using the US Census Bureau's definition of poverty, the working poverty rate seems to have remained relatively stable since 1978. There is quite a bit of controversy around this measurement, namely how the dollar amounts that make up the poverty threshold are calculated. In 1961, the Department of Agriculture came out with an "economy food plan" to be used as a temporarily during an emergency or when a family is in need. This plan did not account for any food consumption outside of the home, and while it was considered nutritious, it was limited in variety and monotonous, thus the temporary designation. The US government took this number and—because the average family at the time spent one-third of their income on food—multiplied it by three. This has remained the standard way to set the poverty thresholds. The food plan has not changed, it has only been adjusted for inflation. One argument is that this is no longer an accurate way to measure poverty because the average lifestyle has changed dramatically since the 1960s

US compared to Europe

Other high-income countries have also experienced declining manufacturing sectors over the past four decades, but most of them have not experienced as much labor market polarization as the United States. Labor market polarization has been the most severe in liberal market economies like the US, Britain, and Australia. Countries like Denmark and France have been subject to the same economic pressures, but due to their more "inclusive" (or "egalitarian") labor market institutions, such as centralized and solidaristic collective bargaining and strong minimum wage laws, they have experienced less polarization.

Cross-national studies have found that European countries' working poverty rates are much lower than the US's. Most of this difference can be explained by the fact that European countries' welfare states are more generous than the US's. The relationship between generous welfare states and low rates of working poverty is elaborated upon in the "Risk factors" and "Anti-poverty policies" sections.

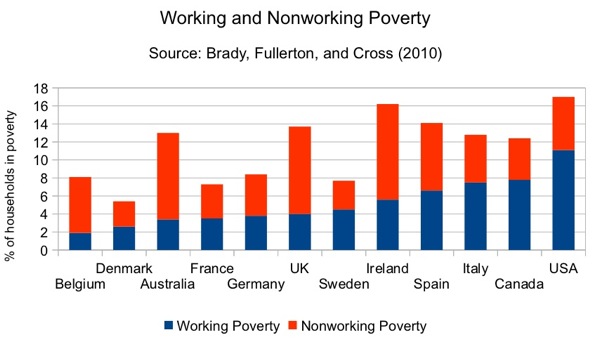

The following graph uses data from Brady, Fullerton, and Cross (2010) to show the working poverty rates for a small sample of countries. Brady, Fullerton, and Cross (2010) accessed this data through the Luxembourg Income Study. This graph measures household, rather than person-level, poverty rates. A household is coded as "poor" if its income is less than 50% of its country's median income. This is a relative, rather than absolute, measure of poverty. A household is classified as "working" if at least one member of the household was employed at the time of the survey. The most important insight contained in this graph is that the US has strikingly higher working poverty rates than European countries.

Risk factors

Race

Minorities in the US are disproportionately affected by poverty. Blacks and Hispanics are twice as likely to be part of the working poor than Whites. In 2017, the rate for Blacks and Hispanics was 7.9%, and 3.9% for Whites, 2.9% for Asians.

Education

Higher levels of education generally leads to lower levels of poverty. However, higher education is not a guarantee of escaping poverty. 5.0% of the working poor have some college experience, 3.2% have an associate degree, and 1.5% have a bachelor's degree or higher. Using the Supplemental Poverty Report and looking at everyone in poverty, not just those working, these percentages actually rise to 14.9% with a high school diploma, 9.7% with some college, and 6.2% with a bachelor's degree of higher. Blacks and Hispanics have higher rates of poverty than Whites and Asians at every education level. Student loan debt in the USA can also contribute to poverty due to capitalized interest if the borrower does not earn enough wages keep up with the loan payments.

Families

Married and cohabiting partners are less likely to experience poverty than individuals and single parents. The percentage of married and cohabiting partners living in poverty in 2018 was 7.7% and 13.9% versus 21.9% for individuals. Single mothers are more likely than single fathers to experience poverty, 25% and 15.1% respectively.

Age

Older workers are less likely to be working and poor than their younger counterparts. The age group with the highest rate of poverty at 8.5% is 20 to 24 year olds, and 16 to 19 year olds at 8.4%. As workers age, the rate of poverty decreases to 5.7% for 25 to 34 year olds and 5% for 35 to 44 year olds. Workers ages 45 to 50, 55 to 64 and 65+ had much lower working poor rates, 3.1%, 2.6% and 1.5%, respectively.

Gender

Women of all races are more likely than men to be classified as working poor, especially if they are single mothers. The overall rate for women in 2017 was 5.3%, compared to 3.8% for men. The rate for Black women and Hispanic women was significantly higher than their male counterparts, at 10% and 9.1%, compared to Black men at 5.6% and Hispanic men at 7.0%. The rate for White women was closer to White males, at 4.5% and 3.5%, respectively. Only Asian women had a lower rate of working poverty than Asian males, at 2.5% and 3.2%, respectively.

Transgender persons are more likely than cisgender men or women to be classified as working poor. In the United States, transgender people are three times more likely than the average population have a household income between $1 and $9,999, and nearly twice as likely to have a household income between $10,000 and $24,999.

Obstacles to uplift

The working poor face many of the same daily life struggles as the nonworking poor, but they also face some unique obstacles. Some studies, many of them qualitative, provide detailed insights into the obstacles that hinder workers' ability to find jobs, keep jobs, and make ends meet. Some of the most common struggles faced by the working poor are finding affordable housing, arranging transportation to and from work, buying basic necessities, arranging childcare, having unpredictable work schedules, juggling two or more jobs, and coping with low-status work.

Housing

Working poor people who do not have friends or relatives with whom they

can live often find themselves unable to rent an apartment of their own.

Although the working poor are employed at least some of the time, they

often find it difficult to save enough money for a deposit on a rental

property. As a result, many working poor people end up in living

situations that are actually more costly than a month-to-month rental.

For instance, many working poor people, especially those who are in some

kind of transitional phase, rent rooms in week-to-week motels.

These motel rooms tend to cost much more than a traditional rental,

but they are accessible to the working poor because they do not require a

large deposit. If someone is unable or unwilling to pay for a room in a

motel, they might live in their car, in a homeless shelter, or on the

street. This is not a marginal phenomenon; in fact, according to the

2008 US Conference of Mayors, one in five homeless people are currently

employed.

Some working poor people are able to access housing subsidies (such as a Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher) to help cover their housing expenses. However, these housing subsidies are not available to everyone who meets the Section 8 income specifications. In fact, less than 25% of people who qualify for a housing subsidy receive one.

Education

The issue with education starts many times with the working poor from

childhood and follows them into their struggle for a substantial income.

Children growing up in families of the working poor are not provided

the same educational opportunities as their middle-class counterpart. In

many cases the low income community is filled with schools that are

lacking necessities and support needed to form a solid education.

This follows students as they continue in education. In many cases this

hinders the possibility for America's youth to continue on to higher

education. The grades and credits just are not attained in many cases,

and the lack of guidance in the schools leaves the children of the

working poor with no degree. Also, the lack of funds for continuing

education causes these children to fall behind. In many cases, their

parents did not continue on into higher education and because of this

have a difficult time finding jobs with salaries that can support a

family. Today a college degree is a requirement for many jobs, and it is

the low skill jobs that usually only require a high school degree or GED. The inequality in available education continues the vicious cycle of families entering into the working poor.

Transportation

Given the fact that many working poor people do not own a car or cannot

afford to drive their car, where they live can significantly limit where

they are able to work, and vice versa.

Given the fact that public transportation in many US cities is sparse,

expensive, or non-existent, this is a particularly salient obstacle.

Some working poor people are able to use their social networks—if they

have them—to meet their transportation needs. In a study on low-income

single mothers, Edin and Lein found that single mothers who had someone

to drive them to and from work were much more likely to be able to

support themselves without relying on government aid.

Basic necessities

Like the unemployed poor, the working poor struggle to pay for basic

necessities like food, clothing, housing, and transportation. In some

cases, however, the working poor's basic expenses can be higher than the

unemployed poor's. For instance, the working poor's clothing expenses

may be higher than the unemployed poor's because they must purchase

specific clothes or uniforms for their jobs.

Also, because the working poor are spending much of their time at

work, they may not have the time to prepare their own food. In this

case, they may frequently resort to eating fast food, which is less healthful and more expensive than home-prepared food.

Childcare

Working poor parents with young children, especially single parents,

face significantly more childcare-related obstacles than other people.

Often, childcare costs can exceed a low-wage earners' income, making

work, especially in a job with no potential for advancement, an

economically illogical activity. However, some single parents are able to rely on their social networks to provide free or below-market-cost childcare. There are also some free childcare options provided by the government, such as the Head Start Program.

However, these free options are only available during certain hours,

which may limit parents' ability to take jobs that require late-night

shifts. The U.S. "average" seems to suggest that for one toddler, in

full-time day care, on weekdays, the cost is approximately $600.00 per

month. But, that figure can rise to well over $1000.00 per month in

major metro areas, and fall to less than $350 in rural areas. The

average cost of center-based daycare in the United States is $11,666 per

year ($972 a month), but prices range from $3,582 to $18,773 a year

($300 to $1,564 monthly), according to the National Association of Child

Care Resource & Referral Agencies.

Work schedules

Many low-wage jobs

force workers to accept irregular schedules. In fact, some employers

will not hire someone unless they have "open availability," which means

being available to work any time, any day.

This makes it difficult for workers to arrange for childcare and to

take on a second job. In addition, working poor people's working hours

can fluctuate wildly from one week to the next, making it difficult for

them to budget effectively and save up money.

Multiple jobs

Many low-wage workers have to work multiple jobs in order to make ends

meet. In 1996, 6.2 percent of the workforce held two or more full- or

part-time jobs. Most of these people held two part-time jobs or one

part-time job and one full-time job, but 4% of men and 2% of women held

two full-time jobs at the same time. This can be physically exhausting and can often lead to short and long-term health problems.

Low-Status Work

Many low-wage service sector jobs require a great deal of customer

service work. Although not all customer service jobs are low-wage or

low-status, many of them are. Some argue that the low status nature of some jobs can have negative psychological effects on workers,

but others argue that low status workers come up with coping

mechanisms that allow them to maintain a strong sense of self-worth. One of these coping mechanisms is called boundary work.

Boundary work happens when one group of people valorize their own

social position by comparing themselves to another group, who they

perceive to be inferior in some way. For example, Newman (1999) found

that fast food workers in New York City cope with the low-status nature

of their job by comparing themselves to the unemployed, who they

perceive to be even lower-status than themselves.

Thus, although the low-status nature of working poor people's jobs may

have some negative psychological effects, some, but probably not all, of

these negative effects can be counteracted through coping mechanisms

such as boundary work.

Anti-poverty policies

Scholars, policymakers, and others have come up with a variety of proposals for how to reduce or eliminate working poverty. Most of these proposals are directed toward the United States, but they might also be relevant to other countries. The remainder of the section outlines the pros and cons of some of the most commonly proposed solutions.

Welfare state generosity

Cross-national studies like Lohmann (2009) and Brady, Fullerton, and Cross (2010) clearly show that countries with generous welfare states have lower levels of working poverty than countries with less-generous welfare states, even when factors like demography, economic performance, and labor market institutions are taken into account. Having a generous welfare state does two key things to reduce working poverty: it raises the minimum level of wages that people are willing to accept, and it pulls a large portion of low-wage workers out of poverty by providing them with an array of cash and non-cash government benefits. Many think that increasing the United States' welfare state generosity would lower the working poverty rate. A common critique of this proposal is that a generous welfare state would not work because it would stagnate the economy, raise unemployment, and degrade people's work ethic. However, as of 2011, most European countries have a lower unemployment rate than the US. Furthermore, although Western European economies' growth rates can be lower than the US's from time to time, their growth rates tend to be more stable, whereas the US's tends to fluctuate relatively severely. Individual states offer financial assistance for child care, but the aid varies widely. Most assistance is administered through the Child Care and Development Block Grants. Many subsidies have strict income guidelines and are generally for families with children under 13 (the age limit is often extended if the child has a disability). Many subsidies permit home-based care, but some only accept a day care center, so check the requirements. However, in an academic research, half of the respondents linked aspirations to their tax refunds for financial support, even though they did not ask for specific governmental aid.

Some states distribute funds through social or health departments or agencies (like this one in Washington State). For example, the Children's Cabinet in Nevada can refer families to providers, help them apply for subsidies and can even help families who want to pay a relative for care. North Carolina's Smart Start is a public/private partnership that offers funding for child care. Check the National Women's Law Center for each state's child care assistance policy.

Wages and benefits

In the conclusion of her book, Nickel and Dimed (2001), Barbara Ehrenreich argues that Americans need to pressure employers to improve worker compensation. Generally speaking, this implies a need to strengthen the labor movement. Cross-national statistical studies on working poverty suggest that generous welfare states have a larger impact on working poverty than strong labor movements. The labor movements in various countries have accomplished this through political parties of their own (labor parties) or strategic alliances with non-labor parties, for instance, when striving to put a meaningful minimum wage in place. The federal government offers a Flexible Spending Account (FSA) that's administered through workplaces.

If a job offers an FSA (also known as a Dependent Care Account), one can put aside up to $5,000 in pre-tax dollars to pay for child care expenses. If both you and your spouse have an FSA, the family limit is $5,000—but you could get as much as $2,000 in tax savings if your combined contributions reach the maximum.

Education and training

Some argue that more vocational training and active labour market policies, especially in growth industries like healthcare and renewable energy, is the solution to working poverty. To be sure, wider availability of vocational training could pull some people out of working poverty, but the fact remains that the low-wage service sector is a rapidly growing part of the US economy. Even if more nursing and clean energy jobs were added to the economy, there would still be a huge portion of the workforce in low-wage service sector jobs like retail, food service, and cleaning. Therefore, it seems clear that any significant reduction in the working poverty rate will have to come from offering higher wages and more benefits to the current, and future, population of service sector workers.

Child support assurance

Given the fact that such a large proportion of working poor households are headed by a single mother, one clear way to reduce working poverty would be to make sure that children's fathers share the cost of child rearing. In cases where the father cannot provide child support, scholars like Irwin Garfinkel advocate for the implementation of a child support guarantee, whereby the government pays childcare costs if the father cannot. Child support is not always a guarantee if the father or mother does not work. For example, if the parent without custody is not working then the parent with custody does not receive any child support unless the non working parent is employed at their job longer than 90 days, excluding if the non begins to work for its a city or government. Also, the government does not pay for childcare cost if you make more than the cut off range (your gross, per county or state.)

Marriage

Households with two wage-earners have a significantly lower rate of working poverty than households with only one wage-earner. Also, households with two adults, but only one wage-earner, have lower working poverty rates than households with only one adult. Therefore, it seems clear that having two adults in a household, especially if there are children present, is more likely to keep a household out of poverty than having just one adult in a household. Many scholars and policymakers have used this fact to argue that encouraging people to get married and stay married is an effective way to reduce working poverty (and poverty in general). However, this is easier said than done. Research has shown that low-income people marry less often than higher-income people because they have a more difficult time finding a partner who is employed, which is often seen as a prerequisite for marriage. Therefore, unless the employment opportunity structure is improved, simply increasing the number of marriages among low-income people would be unlikely to lower working poverty rates.

Ultimately, effective solutions to working poverty are multifaceted. Each of the aforementioned proposals could help reduce working poverty in the United States, but they might have a greater impact if at least a few of them were pursued simultaneously.