From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Mutualism is an anarchist school of thought and economic theory that advocates a socialist society based on free markets and usufructs, i.e. occupation and use property norms. One implementation of this system involves the establishment of a mutual-credit bank that would lend to producers at a minimal interest rate, just high enough to cover administration. Mutualism is based on a version of the labor theory of value

that it uses as its basis for determining economic value. According to

mutualist theory, when a worker sells the product of their labor, they

ought to receive money, goods, or services in exchange that are equal in

economic value, embodying "the amount of labor necessary to produce an

article of exactly similar and equal utility". The product of the worker's labour factors the amount of both mental and physical labour into the price of their product.

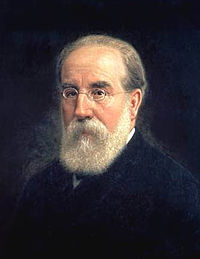

While mutualism was popularized by the writings of anarchist philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and is mainly associated as an anarchist school of thought and with libertarian socialism, its origins as a type of socialism go back to the 18th-century labour movement in Britain first, then France and finally to the working-class Chartist movement. Mutualists oppose individuals receiving income through loans, investments and rent under capitalist social relations.

Although opposed to this type of income, Proudhon expressed that he had

never intended "to forbid or suppress, by sovereign decree, ground rent

and interest on capital. I think that all these manifestations of human

activity should remain free and voluntary for all: I ask for them no

modifications, restrictions or suppressions, other than those which

result naturally and of necessity from the universalization of the

principle of reciprocity which I propose." As long as they ensure the worker's right to the full product of their labour, mutualists support markets and property in the product of labour, differentiating between capitalist private property (productive property) and personal property (private property).

Mutualists argue for conditional titles to land, whose ownership is

legitimate only so long as it remains in use or occupation (which

Proudhon called possession), a type of private property with strong

abandonment criteria. This contrasts with the capitalist non-proviso labour theory of property, where an owner maintains a property title more or less until one decides to give or sell it.

As libertarian socialists, mutualists distinguish their market socialism from state socialism and do not advocate state ownership over the means of production.

Instead, each person possesses a means of production, either

individually or collectively, with trade representing equivalent amounts

of labour in the free market. Benjamin Tucker

wrote of Proudhon that "though opposed to socializing the ownership of

capital, he aimed nevertheless to socialize its effects by making its

use beneficial to all instead of a means of impoverishing the many to

enrich the few ... by subjecting capital to the natural law of

competition, thus bringing the price of its own use down to cost".

Although similar to the economic doctrines of the 19th-century American

individualist anarchists, mutualism favours large industries. Mutualism has been retrospectively characterized sometimes as being a form of individualist anarchism and ideologically situated between individualist and collectivist forms of anarchism. Proudhon described the liberty he pursued as "the synthesis of communism and property". Some consider mutualism part of free-market anarchism, individualist anarchism and market-oriented left-libertarianism, while others regard it as part of social anarchism.

History

Origins

As a term, mutualism has seen a variety of related uses. Charles Fourier first used the French term mutualisme in 1822, although the reference was not to an economic system. The first use of the noun mutualist was in the New-Harmony Gazette by an American Owenite in 1826. In the early 1830s, a French labour organization in Lyons called themselves the Mutuellists. In What Is Mutualism?, the American mutualist Clarence Lee Swartz defined it this way:

A social system based on equal freedom, reciprocity, and

the sovereignty of the individual over himself, his affairs and his

products; realized through individual initiative, free contract,

cooperation, competition and voluntary association for defense against

the invasive and for the protection of life, liberty and property of the

non-invasive.

In general, mutualism can be considered the original anarchy since the mutualist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was the first person to identify himself as an anarchist. Although mutualism is generally associated with anarchism, it is not necessarily anarchist. According to William Batchelder Greene

did not become a "full-fledged anarchist" until the last decade of his

life, but his writings show that by 1850 he had articulated a Christian

mutualism, drawing heavily on the writings of Proudhon's

sometimes-antagonist Pierre Leroux. The Christian mutualist form or anarchist branch of distributism and the works of distributists such as Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement can be considered a form of mutualism, or free-market libertarian socialism, due to their opposition to both state capitalism and state socialism. According to A Mutualist FAQ,

mutualism was "the original form taken by the labor movement, first in

Great Britain and shortly thereafter in France and the rest of Western

Europe. Both mutualist practice and theory arose as part of the broad

current of working class radicalism in England, from around the time of

the publication of Paine's Rights of Man and the organization of

the first Societies of Correspondence in the 1790s, to the Chartist

movement. Mutualism existed for some time as a spontaneous working class

practice before it was formalized in theory."

Proudhon was involved with the Lyons mutualists and later adopted the name to describe his teachings. In What Is Mutualism?, Swartz gives his account of the origin of the term, claiming that "[t]he word 'mutualism' seems to have been first used by John Gray, an English writer, in 1832". When Gray's 1825 Lecture on Human Happiness was first published in the United States in 1826, the publishers appended the Preamble and Constitution of the Friendly Association for Mutual Interests, Located at Valley Forge. 1826 also saw the publication of the Constitution of the Friendly Association for Mutual Interests at Kendal, Ohio. Of Proudhon's philosophy, Geoffrey Ostergaard

summarized, "he argued that working men should emancipate themselves,

not by political but by economic means, through the voluntary

organization of their own labour—a concept to which he attached

redemptive value. His proposed system of equitable exchange between

self-governing producers, organized individually or in association and

financed by free credit, was called 'mutualism'. The units of the

radically decentralized and pluralistic social order that he envisaged

were to be linked at all levels by applying 'the federal principle.'"

The authors of A Mutualist FAQ quote E. P. Thompson's

description of the early working-class movement as mutualism. Thompson

argued that it was "powerfully shaped by the sensibilities of urban

artisans and weavers who combined a 'sense of lost independence' with

'memories of their golden age.' The weavers in particular carried a

strong communitarian and egalitarian sensibility, basing their

radicalism, 'whether voiced in Owenite or biblical language,' on

'essential rights and elementary notions of human fellowship and

conduct.'"

Thompson further wrote: "It was as a whole community that they demanded

betterment, and utopian notions of redesigning society anew at a

stroke—Owenite communities, the universal general strike, the Chartist

Land Plan—swept through them like fire on the common. But essentially

the dream which arose in many different forms was the same—a community

of independent small producers, exchanging their products without the

distortions of masters and middlemen."

Mutualist anti-capitalism originates in the Jacobin-influenced

radicalism of the 1790s, which saw exploitation mainly in taxation and

feudal landlordism in that "government appears as court parasitism:

taxes are a form of robbery, for pensioners and for wars of conquest." In Constantin François de Chassebœuf, comte de Volney's Ruins of Empire,

the nation was divided between those who "by useful laborus contribute

to the support and maintenance of society" and "the parasites who lived

off them", namely "none but priests, courtiers, public accountants,

commanders of troops, in short, the civil, military, or religious agents

of government." This was summarized by the following statement:

People.... What labour do you perform in the society?

Privileged Class. None: we are not made to labour.

People. How then have you acquired your wealth?

Privileged Class. By taking the pains to govern you.

People.

To govern us!... We toil, and you enjoy; we produce and you dissipate;

wealth flows from us, and you absorb it. Privileged men, class distinct

from the people, form a class apart and govern yourselves.

According to the authors of A Mutualist FAQ, "it would be a

mistake to make a sharp distinction between this analysis and the later

critique of capitalism. The heritage of the manorial economy and the

feudal aristocracy blurred the distinction between the state and the

economic ruling class. But such a distinction is largely imaginary in

any social system. The main difference is that manorialism was openly

founded on conquest, whereas capitalism hid its exploitative character

behind a facade of 'neutral' laws."

They further write that "[t]he critique of pre-capitalist authority

structures had many features that could be expanded by analogy to the

critique of capitalism. The mutualist analysis of capitalism as a system

of state-enforced privilege is a direct extension of the

Jacobin/radical critique of the landed aristocracy. The credit and

patent monopolies were attacked on much the same principles as the

radicals of the 1790s attacked seigneural rents. There was a great

continuity of themes from the 1790s through Owenist and Chartist times.

One such theme was the importance of widespread, egalitarian property

ownership by the laboring classes, and the inequity of concentrating

property ownership in the hands of a few non-producers." According to them, this prefigured distributism. Other notable people mentioned as influences on mutualism include John Ball and Wat Tyler as part of the Peasants' Revolt, William Cobbett, the English Dissenter and radical offshoots of Methodism such as the Primitive Methodists and the New Connexion, as well as the more secular versions of republicanism and economic populism going back to the Diggers and the Levellers, the Fifth Monarchists, William Godwin, Robert Owen, Thomas Paine, Thomas Spence and the Quakers.

By 1846, Proudhon was speaking of "mutuality" (mutualité) in his writings, and he used the term "mutualism" (mutuellisme) at least as early as 1848 in his Programme Révolutionnaire. In 1850, Greene used the term mutualism to describe a mutual credit system similar to that of Proudhon. In 1850, the American newspaper The Spirit of the Age, edited by William Henry Channing, published proposals for a mutualist township by Joshua King Ingalls and Albert Brisbane, together with works by Proudhon, Greene, Leroux and others.

Proudhon ran for the French Constituent Assembly

in April 1848 but was not elected, although his name appeared on the

ballots in Paris, Lyon, Besançon and Lille. He was successful in the

complementary elections of 4 June and served as a deputy during the

debates over the National Workshops, created by the 25 February 1848 decree passed by Republican Louis Blanc.

The workshops were to give work to the unemployed. Proudhon was never

enthusiastic about such workshops, perceiving them as charitable

institutions that did not resolve the problems of the economic system.

He was against their elimination unless an alternative could be found

for the workers who relied on the workshops for subsistence.

Proudhon was surprised by the French Revolution of 1848.

He participated in the February uprising and the composition of what he

termed "the first republican proclamation" of the new republic.

However, he had misgivings about the new provisional government headed

by Jacques-Charles Dupont de l'Eure (1767–1855), who since the French Revolution

in 1789 had been a longstanding politician, although often in the

opposition. Proudhon published his perspective for reform, completed in

1849, titled Solution du problème social (Solution of the Social Problem),

in which he laid out a program of mutual financial cooperation among

workers. He believed this would transfer control of economic relations

from capitalists and financiers

to workers. The central part of his plan was establishing a bank to

provide credit at a very low interest rate and issuing exchange notes

that would circulate instead of money based on gold.

19th-century United States

Mutualism was especially prominent in the United States and advocated by American individualist anarchists. While individualist anarchists in Europe are pluralists who advocate anarchism without adjectives and synthesis anarchism, ranging from anarcho-communist to mutualist economic types, most individualist anarchists in the United States advocate mutualism as a libertarian socialist form of market socialism or a free-market socialist form of classical economics.

Mutualism has been associated with two types of currency reform. Labour notes were first discussed in Owenite circles and received their first practical test in 1827 in the Time Store of former New Harmony member and individualist anarchist Josiah Warren.

Mutual banking aimed at the monetization of all forms of wealth and the

extension of free credit. It is most closely associated with William Batchelder Greene, but Greene drew from the work of Proudhon, Edward Kellogg

and William Beck and from the land bank tradition. Within individualist

anarchist circles, mutualism meant non-communist anarchism or

non-communist socialism.

American individualist anarchist

Benjamin Tucker, one of the individualist anarchists influenced by Proudhon's mutualism

Historian Wendy McElroy

reports that American individualist anarchism received an important

influence from three European thinkers. One of the most important

influences was the French political philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon,

whose words "Liberty is not the Daughter But the Mother of Order"

appeared as a motto on Liberty's masthead. Liberty was an influential American individualist anarchist publication by Benjamin Tucker.

For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, "[i]t is

apparent ... that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United

States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its

affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews. ... William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form".

After 1850, Greene became active in labour reform.

He was elected vice-president of the New England Labor Reform League,

the majority of the members holding to Proudhon's scheme of mutual

banking, and in 1869, the Massachusetts Labor Union president. He then publishes Socialistic, Communistic, Mutualistic, and Financial Fragments (1875). He saw mutualism as the synthesis of "liberty and order".

His "associationism ... is checked by individualism. ... 'Mind your own

business,' 'Judge not that ye be not judged.' Over matters which are

purely personal, as for example, moral conduct, the individual is

sovereign as well as over that which he himself produces. For this

reason, he demands 'mutuality' in marriage—the equal right of a woman to

her own personal freedom and property".

In Individual Liberty, Tucker later connected his economic views with those of Proudhon, Warren and Karl Marx,

taking sides with the first two while also arguing against American

anti-socialists who declared socialism as imported, writing:

The economic principles of Modern Socialism are a logical

deduction from the principle laid down by Adam Smith in the early

chapters of his Wealth of Nations, – namely, that labor is the

true measure of price. ... Half a century or more after Smith enunciated

the principle above stated, Socialism picked it up where he had dropped

it, and in following it to its logical conclusions, made it the basis

of a new economic philosophy. ... This seems to have been done

independently by three different men, of three different nationalities,

in three different languages: Josiah Warren, an American; Pierre J.

Proudhon, a Frenchman; Karl Marx, a German Jew. ... That the work of

this interesting trio should have been done so nearly simultaneously

would seem to indicate that Socialism was in the air, and that the time

was ripe and the conditions favorable for the appearance of this new

school of thought. So far as priority of time is concerned, the credit

seems to belong to Warren, the American, – a fact which should be noted

by the stump orators who are so fond of declaiming against Socialism as an imported article.

19th-century Spain

Mutualist ideas found fertile ground in the 19th century in Spain. In

Spain, Ramón de la Sagra established the anarchist journal El Porvenir in A Coruña in 1845, inspired by Proudhon's ideas. The Catalan politician Francesc Pi i Margall became the principal translator of Proudhon's works into Spanish

and later briefly became president of Spain in 1873 while being the

leader of the Democratic Republican Federal Party. According to George Woodcock,

"[t]hese translations were to have a profound and lasting effect on the

development of Spanish anarchism after 1870, but before that time

Proudhonian ideas, as interpreted by Pi, already provided much of the

inspiration for the federalist movement which sprang up in the early

1860's [sic]".

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, "[d]uring the Spanish revolution of 1873, Pi y Margall attempted to establish a decentralized, or cantonalist, political system on Proudhonian lines". Pi i Margall was a dedicated theorist in his own right, especially through book-length works such as La reacción y la revolución (Reaction and Revolution from 1855), Las nacionalidades (Nationalities from 1877) and La Federación (The Federation from 1880). For prominent anarcho-syndicalist Rudolf Rocker,

"[t]he first movement of the Spanish workers was strongly influenced by

the ideas of Pi y Margall, leader of the Spanish Federalists and

disciple of Proudhon. Pi y Margall was one of the outstanding theorists

of his time and had a powerful influence on the development of

libertarian ideas in Spain. His political ideas had much in common with

those of Richard Price, Joseph Priestly [sic], Thomas Paine, Jefferson,

and other representatives of the Anglo-American liberalism of the first

period. He wanted to limit the power of the state to a minimum and

gradually replace it by a Socialist economic order".

First International and Paris Commune

According to a historian of the First International,

G. M. Stekloff, in April 1856, "arrived from Paris a deputation of

Proudhonist workers whose aim it was to bring about the foundation of a

Universal League of Workers. The object of the League was the social

emancipation of the working class, which, it was held, could only be

achieved by a union of the workers of all lands against international

capital. Since the deputation was one of Proudhonists, of course this

emancipation was to be secured, not by political methods, but purely by

economic means, through the foundation of productive and distributive

co-operatives".

Stekloff continues by saying that "[i]t was in the 1863 elections that

for the first time workers' candidates were run in opposition to

bourgeois republicans, but they secured very few votes. ... [A] group of

working-class Proudhonists (among whom were Murat and Tolain, who were

subsequently to participate in the founding of the (First) International

issued the famous Manifesto of the Sixty, which, though extremely

moderate in tone, marked a turning point in the history of the French

movement. For years and years the bourgeois liberals had been insisting

that the revolution of 1789 had abolished class distinctions. The

Manifesto of the Sixty loudly proclaimed that classes still existed.

These classes were the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The latter had

its specific class interests, which none but workers could be trusted to

defend. The inference drawn by the Manifesto was that there must be

independent working-class candidates".

For Stekloff, "the Proudhonists, who were at that date the

leaders of the French section of the International. They looked upon the

International Workingmen's Association as a sort of academy or

synagogue, where Talmudists or similar experts could "investigate" the

workers' problem; wherein the spirit of Proudhon they could excogitate

means for an accurate solution of the problem without being disturbed by

the stresses of a political campaign. Thus Fribourg, voicing the

opinions of the Parisian group of the Proudhonists (Tolain and Co.),

assured his readers that "the International was the greatest attempt

ever made in modern times to aid the proletariat towards the conquest,

by peaceful, constitutional, and moral methods, of the place which

rightly belongs to the workers in the sunshine of civilisation".

According to Stekoff, the Belgian Federation "threw in its lot with the

anarchist International at its Brussels Congress, held in December,

1872. ... [T]hose taking part in the socialist movement of the Belgian

intelligentsia were inspired by Proudhonist ideas which naturally led

them to oppose the Marxist outlook".

Mutualism also had a considerable influence on the Paris Commune. George Woodcock

manifests that "a notable contribution to the activities of the Commune

and particularly to the organization of public services was made by

members of various anarchist factions, including the mutualists Courbet,

Longuet, and Vermorel, the libertarian collectivists Varlin, Malon, and Lefrangais, and the bakuninists Elie and Elisée Reclus and Louise Michel".

21st century

19th-century mutualists considered themselves libertarian socialists and are still considered libertarian socialists today. While oriented towards cooperation, mutualists favour free-market solutions, believing that most inequalities result from preferential conditions created by government intervention. Mutualism is a middle way between classical economics and socialism of the collectivist variety, with some characteristics of both. As for capital goods (manufactured and non-land means of production), mutualist opinion differs on whether these should be common property and commonly managed public assets or private property in the form of worker cooperatives, for as long as they ensure the worker's right to the full product of their labour, mutualists support markets and property in the product of labour, differentiating between capitalist private property (productive property) and personal property (private property).

Contemporary mutualist Kevin Carson considers mutualism to be free-market socialism. Proudhon supported labor-owned cooperative firms and associations, for "we need not hesitate, for we have no choice. ... [I]t is necessary

to form an association among workers ... because without that, they

would remain related as subordinates and superiors, and there would

ensue two ... castes of masters and wage-workers, which is repugnant to a

free and democratic society" and so "it becomes necessary for the

workers to form themselves into democratic societies, with equal

conditions for all members, on pain of a relapse into feudalism". In the preface to his Studies in Mutualist Political Economy, Carson describes this work as "an attempt to revive individualist anarchist

political economy, to incorporate the useful developments of the last

hundred years, and to make it relevant to the problems of the

twenty-first century". Carson holds that capitalism

has been founded on "an act of robbery as massive as feudalism" and

argues that capitalism could not exist in the absence of a state. He

says that "[i]t is state intervention that distinguishes capitalism from

the free market".

Carson does not define capitalism in the idealized sense, but he says

that when he talks about capitalism, he is referring to what he calls actually existing capitalism. Carson believes the term laissez-faire

capitalism is an oxymoron because capitalism, he argues, is an

"organization of society, incorporating elements of tax, usury,

landlordism, and tariff, which thus denies the Free Market while

pretending to exemplify it". Carsons says he has no quarrel with anarcho-capitalists who use the term laissez-faire

capitalism and distinguish it from actually existing capitalism.

Although Carson says he has deliberately chosen to resurrect an old

definition of the term. Many anarchists, including mutualists, continue to use the term and do not consider it an old definition. Carson argues that the centralization of wealth into a class hierarchy is due to state intervention to protect the ruling class by using a money monopoly, granting patents and subsidies to corporations, imposing discriminatory taxation and intervening militarily to gain access to international markets. Carson's thesis is that an authentic and free market economy

would not be capitalism as the separation of labour from ownership and

the subordination of labour to capital would be impossible, bringing a

classless society where people could easily choose between working as a

freelancer, working for a living wage, taking part of a cooperative, or being an entrepreneur. As Benjamin Tucker

before, Carson notes that a mutualist free-market system would involve

significantly different property rights than capitalism, particularly

regarding land and intellectual property.

Following Proudhon, mutualists are libertarian socialists who consider themselves part of the market socialist tradition and the socialist movement. However, some contemporary mutualists outside the classical anarchist tradition, such as those involved in the market-oriented left-libertarianism within the Alliance of the Libertarian Left and the Voluntary Cooperation Movement, abandoned the labour theory of value and prefer to avoid the term socialist due to its association with state socialism throughout the 20th century. Nonetheless, those contemporary mutualists are part of the libertarian left and "still retain some cultural attitudes, for the most part, that set them off from the libertarian right.

Most of them view mutualism as an alternative to capitalism, and

believe that capitalism as it exists is a statist system with

exploitative features".

According to historian James J. Martin, the individualist anarchists in the United States were socialists whose support for the labour theory of value made their libertarian socialist form of mutualism a free-market socialist alternative to capitalism and Marxism.

Theory

The primary aspects of mutualism are free association, free banking, reciprocity in the form of mutual aid, workplace democracy, workers' self-management, gradualism and dual power. Mutualism is often described by its proponents as advocating an anti-capitalist free market.

Mutualists argue that most of the economic problems associated with

capitalism each amount to a violation of the cost principle, or as Josiah Warren interchangeably said, the cost the limit of price. It was inspired by the labour theory of value, which was popularized—although not invented—by Adam Smith

in 1776 (Proudhon mentioned Smith as an inspiration). The labor theory

of value holds that the actual price of a thing (or the true cost) is

the amount of labor undertaken to produce it. In Warren's terms of his cost the limit of price

theory, cost should be the limit of price, with cost referring to the

amount of labour required to produce a good or service. Anyone who sells

goods should charge no more than the cost to himself of acquiring these

goods.

Contract and federation

Mutualism

holds that producers should exchange their goods at cost-value using

contract systems. While Proudhon's early definitions of cost-value were

based on fixed assumptions about the value of labour hours, he later

redefined cost-value to include other factors such as the labour

intensity, the nature of the work involved, etc. He also expanded his

notions of contract into expanded notions of federation. Proudhon argued:

I have shown the contractor, at the birth of industry,

negotiating on equal terms with his comrades, who have since become his

workmen. It is plain, in fact, that this original equality was bound to

disappear through the advantageous position of the master and the

dependent position of the wage-workers. In vain does the law assure the

right of each to enterprise. ... When an establishment has had leisure

to develop itself, enlarge its foundations, ballast itself with capital,

and assure itself a body of patrons, what can a workman do against a

power so superior?

Dual power and gradualism

Dual

power is the process of building alternative institutions to the ones

that already exist in modern society. Initially theorized by Proudhon,

it has become adopted by many anti-state movements such as agorism and autonomism. Proudhon described it as follows:

Beneath the governmental machinery, in the shadow of

political institutions, out of the sight of statemen and priests,

society is producing its own organism, slowly and silently; and

constructing a new order, the expression of its vitality and autonomy.

As Proudhon also theorized it, dual power should not be confused with the dual power popularized by Vladimir Lenin. Proudhon's meaning refers to a more specific scenario where a

revolutionary entity intentionally maintains the structure of the

previous political institutions until the power of the previous

institution is weakened enough such that the revolutionary entity can

overtake it entirely. Dual power, as implemented by mutualists, is the

development of the alternative institution itself.

Free association

Mutualists

argue that association is only necessary where there is an organic

combination of forces. An operation requires specialization and many

different workers performing tasks to complete a unified product, i.e. a

factory. In this situation, workers are inherently dependent on each

other; without association, they are related as subordinate and

superior, master and wage-slave. An operation that an individual can

perform without the help of specialized workers does not require

association. Proudhon argued that peasants do not require societal form

and only feigned association for solidarity in abolishing rents, buying

clubs, etc. He recognized that their work is inherently sovereign and

free. In commenting on the degree of association that is preferable, Proudhon wrote:

In cases in which production requires great division of

labour, it is necessary to form an association among the workers ...

because without that they would remain isolated as subordinates and

superiors, and there would ensue two industrial castes of masters and

wage workers, which is repugnant in a free and democratic society. But

where the product can be obtained by the action of an individual or a

family, ... there is no opportunity for association.

For Proudhon, mutualism involved creating industrial democracy.

In this system, workplaces would be "handed over to democratically

organised workers' associations. ... We want these associations to be

models for agriculture, industry and trade, the pioneering core of that

vast federation of companies and societies woven into the common cloth

of the democratic social Republic".

Under mutualism, workers would no longer sell their labour to a

capitalist but rather work for themselves in co-operatives. Proudhon

urged "workers to form themselves into democratic societies, with equal

conditions for all members, on pain of a relapse into feudalism". This

would result in "[c]apitalistic and proprietary exploitation, stopped

everywhere, the wage system abolished, equal and just exchange

guaranteed".

As Robert Graham

notes, "Proudhon's market socialism is indissolubly linked to his

notions of industrial democracy and workers' self-management".

K. Steven Vincent notes in his in-depth analysis of this aspect of

Proudhon's ideas that "Proudhon consistently advanced a program of

industrial democracy which would return control and direction of the

economy to the workers". For Proudhon, "strong workers' associations ...

would enable the workers to determine jointly by election how the

enterprise was to be directed and operated on a day-to-day basis".

Mutual credit

American individualist anarchist

Lysander Spooner, who supported free banking and mutual credit

Mutualists support mutual credit and argue that free banking

should be taken back by the people to establish systems of free credit.

They contend that banks have a monopoly on credit, just as capitalists

have a monopoly on the means of production and landlords have a land

monopoly. Banks create money by lending out deposits that do not belong

to them and then charging interest on the difference. Mutualists argue

that by establishing a democratically run mutual savings bank or credit union,

it would be possible to issue free credit so that money could be

created for the participants' benefit rather than the bankers' benefit.

Individualist anarchists noted for their detailed views on mutualist

banking include Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, William Batchelder Greene and Lysander Spooner.

In a session of the French legislature, Proudhon proposed a government-imposed income tax to fund his mutual banking scheme, with some tax brackets reaching as high as 331⁄3 percent and 50 percent, but the legislature turned it down. This income tax Proudhon proposed to fund his bank was to be levied on rents, interest, debts and salaries.

Specifically, Proudhon's proposed law required all capitalists and

stockholders to disburse one-sixth of their income to their tenants and

debtors and another sixth to the national treasury to fund the bank.

This scheme was vehemently objected to by others in the legislature, including Frédéric Bastiat. The reason for rejecting the income tax was that it would result in economic ruin and violate "the right of property". Proudhon once proposed funding a national bank with a voluntary tax of 1% in his debates with Bastiat. Proudhon also argued for the abolition of all taxes.

Property

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was an anarchist and socialist philosopher who articulated thoughts on the nature of property. He claimed that "property is theft", "property is liberty", and "property is impossible". According to Colin Ward,

Proudhon did not see a contradiction between these slogans. This was

because Proudhon distinguished between what he considered to be two

distinct forms of property often bound up in a single label. To the

mutualist, this is the distinction between property created by coercion

and property created by labour. Property is theft "when it is related to

a landowner or capitalist whose ownership is derived from conquest or

exploitation and [is] only maintained through the state, property laws,

police, and an army". Property is freedom for "the peasant or artisan

family [who have] a natural right to a home, land [they may]

cultivate, ... to tools of a trade" and the fruits of that

cultivation—but not to ownership or control of the lands and lives of

others. The former is considered illegitimate property, while the latter

is legitimate property. Some individualist anarchists and followers of Proudhon's mutualism, such as Benjamin Tucker, started calling possession property or private property, causing confusion within the anarchist movement and among other socialists.

Proudhon argued that property in the product of labour is

essential to liberty, while property that strayed from possession

("occupancy and use") was the basis for tyranny and would lead society

to destroy itself.

The conception of entitlement property as a destructive force and

illegitimate institution can be seen in this quote by Proudhon, who

argued:

Then if we are associated for the sake of liberty,

equality, and security, we are not associated for the sake of property;

then if property is a natural right, this natural right is not social,

but anti-social. Property and society are utterly irreconcilable

institutions. It is as impossible to associate two proprietors as to

join two magnets by their opposite poles. Either society must perish, or

it must destroy property. If property is a natural, absolute,

imprescriptible, and inalienable right, why, in all ages, has there been

so much speculation as to its origin? – for this is one of its

distinguishing characteristics. The origin of a natural right! Good God!

who ever inquired into the origin of the rights of liberty, security,

or equality?

In What Is Mutualism?, Clarence Lee Swartz wrote:

It is, therefore, one of the purposes of Mutualists, not

only to awaken in the people the appreciation of and desire for freedom,

but also to arouse in them a determination to abolish the legal

restrictions now placed upon non-invasive human activities and to

institute, through purely voluntary associations, such measures as will

liberate all of us from the exactions of privilege and the power of

concentrated capital.

Swartz also argued that mutualism differs from anarcho-communism

and other collectivist philosophies by its support of private property,

writing: "One of the tests of any reform movement with regard to

personal liberty is this: Will the movement prohibit or abolish private

property? If it does, it is an enemy of liberty. For one of the most

important criteria of freedom is the right to private property in the

products of ones labor. State Socialists, Communists, Syndicalists and

Communist-Anarchists deny private property." However, Proudhon warned that a society with private property would lead to statist relations between people, arguing:

The purchaser draws boundaries, fences himself in, and

says, 'This is mine; each one by himself, each one for himself.' Here,

then, is a piece of land upon which, henceforth, no one has right to

step, save the proprietor and his friends; which can benefit nobody,

save the proprietor and his servants. Let these multiply, and soon the

people ... will have nowhere to rest, no place of shelter, no ground to

till. They will die of hunger at the proprietor's door, on the edge of

that property which was their birth-right; and the proprietor, watching

them die, will exclaim, 'So perish idlers and vagrants.'

Unlike capitalist

private-property supporters, Proudhon stressed equality. He thought

that all workers should own property and have access to capital,

stressing that in every cooperative, "every worker employed in the

association [must have] an undivided share in the property of the

company".

This distinction Proudhon made between different kinds of property has

been articulated by some later anarchist and socialist theorists as one

of the first distinctions between private property and personal property, with the latter having direct use-value to the individual possessing it. For Proudhon, as he wrote in the sixth study of his General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century, the capitalist's employee was "subordinated, exploited: his permanent condition is one of obedience".

Usufruct

Mutualists believe that land should not be a commodity

to be bought and sold, advocating for conditional titles to land based

on occupancy and use norms. Mutualists argue whether an individual has a

legitimate claim to land ownership if he is not currently using it but

has already incorporated his labour into it. All mutualists agree that

everything produced by human labour and machines can be owned as personal property. Mutualists reject the idea of non-personal property and non-proviso Lockean sticky property. Any property obtained through violence, bought with money gained through exploitation, or bought with money that was gained violating usufruct property norms is considered illegitimate.

According to mutualist theory, the main problem with capitalism

is that it allows for non-personal property ownership. Under these

conditions, a person can buy property they do not physically use with

the only goal of owning said property to prevent others from using it,

putting them in an economically weak position, vulnerable enough to be

controlled and exploited. Mutualists argue that this is historically how

certain people were able to become capitalists. According to mutualism, capitalists make money by exercising power rather than labouring. Over time, under these conditions, there emerged a minority class of individuals who owned all the means of production

as non-personal property (the capitalist class) and a large class of

individuals with no access to the means of production (the labouring

class). The labouring class does not have direct access to the means of

production and therefore is forced to sell the only thing they can to

survive, i.e. their labour power,

giving up their freedom to someone who owns the means of production in

exchange for a wage. A worker's wage is always less than the value of

the goods and services he produces. If an employer pays a labourer equal

to the value of the goods and services he produces, then the capitalist

would break even at most. In reality, the capitalist pays his worker

less, and after subtracting overhead,

the remaining difference is exploited profit which the capitalist has

gained without working. Mutualists point out that the money capitalists

use to buy new means of production is the surplus value they exploit from labourers.

Mutualists also argue that capitalists maintain ownership of

their non-personal properties because they support state violence by

funding election campaigns. The state

protects capitalist non-personal property ownership against direct

occupation and use by the public in exchange for money and election

support. Capitalists can then continue buying labour power and the means

of production as non-personal property and extracting surplus value

from more labourers, continuing the cycle. Mutualist theory states that

by establishing usufruct property norms, exclusive non-personal

ownership of the means of production by the capitalist class would be

eliminated. The labouring classes would then have direct access to means

of production, enabling them to work and produce freely in worker-owned

enterprises while retaining the full value of whatever they sell. Wage labour in the form of wage slavery

would be eliminated, and it would be impossible to become a capitalist

because the widespread labour market would no longer exist. No one would

be able to own the means of production in the form of non-personal

property, two ingredients necessary for labour exploitation. This would

result in the capitalist class labouring with the rest of society.

Criticism

Anarchism

In Europe, a contemporary critic of Proudhon was the early libertarian communist Joseph Déjacque, who was able to serialise his book L'Humanisphère, Utopie anarchique (The Humanisphere: Anarchic Utopia) in his periodical Le Libertaire, Journal du Mouvement Social (Libertarian: Journal of Social Movement), published in 27 issues from 9 June 1858 to 4 February 1861 while living in New York.

Unlike and against Proudhon, he argued that "it is not the product of

his or her labor that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction

of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature". In his critique of Proudhon, Déjacque also coined the word libertarian

and argued that Proudhon was merely a liberal, a moderate, suggesting

he become "frankly and completely an anarchist" instead by giving up all

forms of authority and property. Since then, the word libertarian

has been used to describe this consistent anarchism which rejected

private and public hierarchies along with property in the products of

labour and the means of production. Libertarianism is frequently used as

a synonym for anarchism and libertarian socialism.

One area of disagreement between anarcho-communists and mutualists stems from Proudhon's alleged advocacy of labour vouchers to compensate individuals for their labour and markets or artificial markets

for goods and services. However, the persistent claim that Proudhon

proposed a labour currency has been challenged as a misunderstanding or

misrepresentation. Like other anarcho-communists, Peter Kropotkin advocated the abolition of labour remuneration and questioned, "how can this new form of wages, the labor note,

be sanctioned by those who admit that houses, fields, mills are no

longer private property, that they belong to the commune or the nation?" According to George Woodcock, Kropotkin believed that a wage system, whether "administered by Banks of the People or by workers' associations through labor cheques", is a form of compulsion.

Collectivist anarchist Mikhail Bakunin was an adamant critic of Proudhonian mutualism as well,

stating: "How ridiculous are the ideas of the individualists of the

Jean Jacques Rousseau school and of the Proudhonian mutualists who

conceive society as the result of the free contract of individuals

absolutely independent of one another and entering into mutual relations

only because of the convention drawn up among men. As if these men had

dropped from the skies, bringing with them speech, will, original

thought, and as if they were alien to anything of the earth, that is,

anything having social origin". Bakunin also specifically criticized Proudhon,

stating that "[d]espite all his efforts to free himself from the

traditions of classical idealism, Proudhon remained an incorrigible

idealist all his life, swayed at one moment by the Bible and the next by

Roman Law (as I told him two months before he died)."

According to Paul McLaughlin, Bakunin held that "'Proudhon, in spite of

all his efforts to shake off the tradition of classical idealism,

remained all his life an incorrigible idealist', 'unable to surmount

idealistic phantoms' in spite of himself. It is Bakunin's purpose to rid

Proudhon's libertarian thought of its metaphysicality, that is, to

naturalize his anarchism — thereby overcoming its abstract, indeed

reactionary, individualism and transforming it into a social anarchism."

Capitalism

The

pro-capitalism criticism is due to the different conceptions of

property rights between capitalism and mutualism. The latter supports

free access to capital, the means of production and natural resources,

arguing that permanent private ownership of land and capital results in

monopolization without equal liberty

of access. Mutualism also argues that a society with capitalist private

property inevitably leads to statist relations between people.