Lectures at the Collège de France | Author | Michel Foucault |

|---|

| Original title | Lectures at the Collège de France series |

|---|

| Translator | Graham Burchell |

|---|

| Country | France |

|---|

| Language | French |

|---|

| Published | St Martin's Press

- Lectures on the Will to Know (1970–1971)

- Penal Theories and Institutions (1971–1972)

- The Punitive Society (1972–1973)

- Psychiatric Power (1973–1974)

- Abnormal (1974–1975)

- Society Must be Defended (1975–1976)

- Security, Territory, Population (1977–1978)

- The Birth of Biopolitics (1978–1979)

- On the Government of the Living (1979–1980)

- Subjectivity and Truth (1980-1981)

- The Hermeneutics of the Subject (1981-1982)

- The Government of Self and Others (1982-1983)

- The Courage of Truth (1983-1984)

|

|---|

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

|---|

On the proposal of Jules Vuillemin, a chair in the department of Philosophy and History was created at the Collège de France to replace the late Jean Hyppolite. The title of the new chair was The history of systems of thought and it was created on November 30, 1969. Vuillemin put forward Michel Foucault

to the general assembly of professors and Foucault was duly elected on

12 April 1970. He was 44 years old, and at the time was relatively

unknown beyond the borders of his native France. As required by this

appointment, he held a series of public lectures from 1970 until his

death in 1984 (excepting a sabbatical year in 1976–1977). These

lectures, in which he further advanced his work, were summarised from

audio recordings and edited by Michel Senellart. They were subsequently

translated into English and further edited by Graham Burchell and

published posthumously by St Martin's Press.

Lectures On The Will To Know (1970–1971)

This was an important time for Foucault and marks an important switch

of methodology from 'archaeology' to 'genealogy' (according to Foucault

he never abandoned the archaeology method). This was also a period of

transition of thought for Foucault; the Dutch TV-televised Foucault Noam Chomsky Human nature Justice versus Power debate

of November 1971 at the Eindhoven University of Technology appears at

this exact time period as his first inaugural lecture were delivered at

the Collège de France

entitled "the Order Of Discourse" delivered on 2 December 1970

(translated and published into English as "The Discourse On Language")

then a week later (9 December 1970) his first ever full inaugural

lecture course was delivered at the Collège de France

"The Will to Knowledge" course Foucault promised to explore; "fragment

by fragment," the "morphology of the will to knowledge," through

alternating historical periods, inquiries and theoretical questioning.

The lectures produced were called "Lectures On The Will To Know"; all of

this within a space of a year.

The first phase of Foucault's thought is characterized by

knowledge construction of various types and how each thread of knowledge

systems combine together to produce a series of networks (Foucault uses

the term 'Grille') to produce a successful fully functional 'subject'

and a workable fully functional human society. Foucault uses the terms epistemological indicators and epistemological breaks

to show, contrary to popular opinion, that these "indicators" and

"breaks" require skilled trained technical group of 'specialists' in the

various knowledge fields and a trained rigorous professionalized

regulatory body of which know-how on behalf of those who use the terms

(discourse formations or "speech/discourse") with a professional body

that can make the terms used stand up to further rational scrutiny.

Scientific knowledge for Foucault isn't an advancement for human

progress as is so often portrayed by the human sciences (such as the

humanities and the social sciences) but is much more of a subtle method

of organizing and producing firstly an individual subject, and secondly,

a fully functional society functioning as a self-replicated control

apparatus not as a group of 'free' atomized individuals but as a

collective societal, organised (or drilled) unit both in terms of

industrial Production, labour power

and a militarily organized unit (in the guise of armies) which is

beneficial for the production of "epistemological indicators" or

"breaks" enabling society to "control itself" rather than have external

factors (such as the state for example) to do the job.

In the inaugural lecture course "The Will To Know" Foucault goes

into detail on how the 'natural order of things' from the 16th century

transpired into a fully organised human society which includes a "Governmentality"

apparatus and a complex machine (by "governmentality", Foucault means a

state apparatus which is conceived as a scientific machine) as a

rational organizing principle. This was the first time (contrary to

popular opinion that this was a rather late invention in Foucault's

thought) that Foucault started to go into the Greek dimensions of his

thought of which he would return to in later lectures towards the end of

his life. First of all a few pointers should be made explicit on

certain points. Foucault mentions the western notions of money, production and trade

(Greek society) starting about 800 BCE to 700 BCE. However, other

'non-western' societies also had these very same problems and is

automatically assumed by some historians that these were entirely western inventions. This isn't entirely true; China and India for example had the most sophisticated trading and monetary institutions by the 6th century B.C.E., indeed the concept of a corporation existed in India from at least 800 BCE and lasted until at least 1000 C.E.

Most importantly there was a social security

system in India at this time. Foucault begins his notions from these

lectures on the very notion of truth and the 'Will to knowledge' and the

challenge is on when Foucault asks the very question of the entire

western philosophical and political tradition: Namely knowledge (at

least scientific knowledge) and its close association with truth is

entirely desirable and is politically and philosophically natural and

neutral. First of all Foucault puts these notions (at least its

political notions) to a thorough test, firstly, Foucault asks the

politically 'neutral' question on the very first appearance of money

which became not only an important economic symbol but above all else

became a measure of value and a unit of account.

Money once established as a social process and social reality had

(if one could say the word) an extremely rocky and precarious history.

First of all while it had a social reality but the actual social

authority to use money didn't develop a standard practice or knowledge

on how to use it; it was rather undisciplined. Kings and emperors could

squander large taxation revenues with impunity regardless of the

consequences. They could default on repayments on loans as witnessed

during the Hundred Years' War and During the Anglo-French War (1627-1629).

Above all else kings and monarchs could take out forced loans and get

others(their subjects) to pay for these forced loans and to add insult

to injury get them to pay interest on the loans at extortionate rates of

interest charged on the loans because they and their advisers regarded

it as their own 'income'. However, whole societies were dependent on

money particularly when the whole of society had to use and be ready for

its function.

Money took at least 3,000 years of history to get a more disciplined

approach and became the sole prerogative of the fiscal responsibility of

the state after the medieval 'order of things' was entirely dismantled

'to get it right' namely; the ruthlessness and rigorous efficiency

needed for its proper function and it wasn't until the 16th century with

the advent of modern political economy with its analysis of production, labour and trade you then get a sense of why money, particularly its relationship with capital and its complex relationship with the rest of society conversion, from labour power into money via the essential route of surplus value

became a much maligned and misunderstood category and hot potato. This

is where Foucault is at his most profound. Foucault now is asking how is

it that modern western political economy, together with political philosophy and political science

came to ask the question concerning money but was utterly perplexed by

it (this is a question that particularly irritated and irked Karl Marx

throughout his life)? That money and its various association with

production, labour, government and trade was beyond doubt but its exact

relationship with the rest of society was entirely missed by economists

but yet still its version of events was entirely accepted as true?

Foucault begins to try to go into the whole production of truth (both

philosophical and political) its whole "breaks" "discontinuity"

'epistemological unconscious' and theoretical splitting "Episteme".

From this Greek period starting from 800 BCE Foucault pursues the path

of scientific and political knowledge the emergence and conditions of

possibility for philosophical knowledge and ends up with "the problem of

political knowledge (i.e. Aristotelian

notions of the political animal) of what is necessary in order to

govern the city and put it right." He then divided his work on the

history of systems of thought into three interrelated parts, the

"re-examination of knowledge, the conditions of knowledge, and the

knowing subject."

Penal Theories and Institutions (1971–1972)

In these lectures, to be published in English in 2020, Foucault used the first precursor of Discipline and Punish

to study the foundations of what he calls "disciplinary institutions"

(punitive power) and the productive dimensions of penalty.

The Punitive Society (1972–1973)

In these lectures, published in English in 2015, continued the

investigation of power and penal institutions begun in 1971-2. Foucault

spent a lot of time during this period trying to make intelligible the

internal and external dynamics of what we call the prison. He

questioned, "What are the relations of power which made possible the

historical emergence of something like the prison?". This was correlated

to three terms; firstly 'measure' "a means of establishing or restoring

order, the right order, in the combat of men or the elements; but also a

matrix of mathematical and physical knowledge."(treated in more detail

in The Will To Knowledge lectures of 1971); Secondly the

'inquiry' "a means of establishing or restoring facts, events, actions,

properties, rights; but also a matrix of empirical knowledge and natural

sciences"(from the 1972 lectures Theories On Punishment and Penal Theories and Institutions)

and thirdly 'the examination' treated as "the permanent control of the

individual, like a permanent test with no endpoint". Foucault links the

examination with 18th century Political economy and the productive labourers with the wealth they produce and the forces of production.

Abnormal (1974–1975)

Influenced by the work of Georges Canguilhem,

in these lectures (first published in English in 2003) Foucault

explored how power defined the categories of "normality" and

"abnormality" in modern psychiatry.

"Society Must Be Defended" (1975–1976)

This series of lectures forms a trilogy with Security, Territory, Population and The Birth of Biopolitics, and it contains Foucault's first discussion of biopower.

It also contains an explanation of the term "civil war" in the form of

rigorous treatment of a working definition. Foucault goes into great

detail how power (as Foucault saw it) becomes a battleground drifting

from civil war to generalized pacification of the individual and

particularly the systems he (the individual) relies upon and to which he

gives loyalty: "According to this hypothesis, the role of political

power is perpetually to use a sort of silent war to re-inscribe that

relationship of force, and to re-inscribe it in institutions, economic

inequalities, language, and even the bodies of individuals." Foucault

begins to explain that this generalized form of power is not only rooted

in disciplinary institutions

but is also concentrated in "political sovereignty, the military, and

war," so it is in turn spread evenly throughout modern society as a

network of domination.

Foucault then discusses what lies behind the "academic chestnut"

which could not be deciphered by his historical predecessors: namely the

disjointed and discontinuous movement of history and power (bio-power).

What is meant by this? For Foucault's predecessors, history was

concerned by deeds of monarchs and a full list of their accomplishments

in which the sovereign is presented in the text as doing all things

'great,' added to this 'greatness' of deeds this 'greatness' of the

sovereign was accomplished all by the sovereign himself without any

help; monument building, allegedly built by the monarch, without any

help from skilled and trained professionals serves as a perfectly good

example of the sovereign "greatness". However, for Foucault, this is not

the case. Foucault's genealogy comes into play here where Foucault

tries to build a bridge between two theoretical notions: disciplinary

power (disciplinary institutions) and biopower. He investigates the constant shift throughout history between these two 'paradigms,'

and what developments-from these two 'paradigms' became new subjects.

The previous historical dimensions so often portrayed by historians

Foucault argues, was sovereign history, which acts as a ceremonial tool

for sovereign power "It glorifies and adds lustre to power. History

performs this function in two modes: (1) in a "genealogical" mode

(understood in the simple sense of that term) that traces the lineage of

the sovereign. By the time of the 17th century with the development of mercantilism, statistics (mathematical statistics) and political economy this reaches a most vitriolic and vicious form later to be called nation states

where whole populations were involved (in the guise of armies both

industrial and military), in which a continuous war is enacted out not

amongst ourselves (the population) but in a struggle for the state's

very existence which ultimately leads to a "thanatopolitics" (a

philosophical term that discusses the politics of organizing who should

live and who should die (and how) in a given form of society) of the

population on a large industrial scale.

This is where Foucault discusses a "counterhistory" of "race struggle or

race war." According to Foucault, Marx and Engels used or borrowed the

term "race" and transversed the term race into a new term called "class struggle" which later Marxist accepted and began to use. This is more partly to do with Marx's antagonistic relationship with Carl Vogt who for his time was a convinced polygenist which Marx and Engels had inherited Vogt's belief. Foucault quotes letters written by Marx to Engels in 1854 and Joseph Weydemeyer in 1852

Finally,

in your place I should in general remark to the democratic gentlemen

that they would do better first to acquaint themselves with bourgeois

literature before they presume to yap at the opponents of it. For

instance, these gentlemen should study the historical works of Augustin Thierry, François Guizot, John Wade,

and others in order to enlighten themselves as to the past 'history of

classes', where the history of the revolutionary project and of

revolutionary practice is indissoluble from this counterhistory of races.

Foucault challenges the traditional notions of racism in explaining

the operation of the modern state. When Foucault talks of racism he is

not talking about what we might traditionally understand it to be–an

ideology, a mutual hatred. In Foucault's reckoning modern racism is tied

to power, making it something far more profound than traditionally

assumed.

Tracing the genealogy of racism, Foucault proposes that 'race',

previously used to describe the division between two opposing societal

groups distinguished from one another for example by religion or

language, came to be conceived in the late 18th century in biological

terms. The concept of "race war" that referred to conflict over the

legitimacy of the power of the established sovereign, was "reformulated"

into a struggle for existence driven by concern about the biopolitical

purity of the population as a single race that could be threatened from

within its own body. For Foucault "racism is born at the point when the

theme of racial purity replaces that of race struggle" (p. 81).

For Foucault, racism "is an expression of a schism within society

... provoked by the idea of an ongoing and always incomplete cleaning

of the social body…it structures social fields of action, guides

political practice, and is realized through state apparatuses…it is

concerned with biological purity and conformity with the norm"

(pp.43–44).

In modern states, racism is not defined by the action of individuals,

rather it is vested in the State and finds form in its structures and

operation – it is state racism.

State racism serves two functions. Firstly, it makes it possible

to divide the population into biological groups, "good and bad" or

"superior or inferior" 'races'. Fragmented into subspecies, the

population can be brought under State control. Secondly, it facilitates a

dynamic relationship between the life of one person and the death of

another. Foucault is clear that this relationship is not one of warlike

confrontation but rather a biological one, that is not based on the

individual but rather on life in general "the more inferior species die

out, the more abnormal individuals are eliminated the fewer degenerates

there will be in the species as a whole, and the more I – as species

rather than individual – can live, the stronger I will be, the more

vigorous I will be, I will be able to proliferate" (p.255)

In effect race, defined in biological terms, "furnished the

ideological foundation for identifying, excluding, combating, and even

murdering others, all in the name of improving life not of an individual

but of life in general" (p. 42).

What is important here is that racism, inscribed as one of the modern

state's basic techniques of power, allows enemies to be treated as

threats, not political adversaries. But through what mechanism are these

threats treated? Here the technologies of power described by Foucault

become important.

Foucault argues that new technologies of power emerged in the

second half of the 18th century, which Foucault termed biopolitics and

biopower(Foucault uses both terms synonymously), these technologies

focused on man-as-species and were concerned with optimising the state

of life, with taking control of life and intervening to "make live and

let die".

Importantly, Foucault argues, the technologies did not replace the

technologies of sovereign power with their exclusive focus on

disciplining the individual body to be more productive by punishing or

killing individuals, but embedded themselves into them. It was in

exploring how this new power, with life as its object, could come to

include the power to kill that Foucault theorizes the emergence of state

racism.

Foucault argues that the modern state must at some point become

involved with racism in order to function since once a State functions

in a biopolitical mode it is racism alone that can justify killing.

Determined as a threat to the population, the State can take action to

kill in the name of keeping the population safe and thriving, healthy

and pure. It is racism that allows the right to kill to be squared off

with a power that seeks to improve life. State racism delivers actions

that while appearing to derive from altruistic intentions, veil the

murder of the "Other"

Following this argument to its logical end, it is only when there is

never a need for the State to claim the right to kill or to let die that

State racism will disappear.

Since killing is predicated on racism, it follows that the "most murderous states are also the most racist" (p.258).

Foucault refers to the way in which Nazism and the state socialism of

the Soviet Union dealt with ethnic or social groups and their political

adversaries as examples of this.

Threats, however, can change over time and here the utility of

'race' a concept comes into its own. While never defining 'race',

Foucault suggests that the word 'race' is "not pinned to a stable

biological meaning" (p. 77).

with the implication that it is a concept that is socially and

historically constructed where a discourse of truth is enabled. This

makes 'race' something that is easy for the State to adopt and exploit

for its own purpose. 'Race' becomes a technology that is used by the

state to structure threats and to make decisions over the life and death

of sub-populations. In this way it helps to explain how the idea of

'race' or cultural difference are used to wage wars such as the "war on

terror" or the "humanitarian war" in East Timor.

Security, Territory, Population (1977–1978)

The course deals with the genesis of a political knowledge that

was to place at the centre of its concerns the notion of population and

the mechanisms capable of ensuring its regulation but even of its

procedures and means employed to ensure, in a given society, "the

government of men". A transition from a "territorial state" to a

"population state" (Nation state)?

Foucault examines the notion of biopolitics and biopower as a new technology of power over populations that is distinct from punitive disciplinary systems, by tracing the history of governmentality,

from the first centuries of the Christian era to the emergence of the

modern nation state. These lectures illustrate a radical turning point

in Foucault's work at which a shift to the problematic of the government

of self and others occurred.

Foucault's challenge to himself in these series of lectures is to

try and decipher the genealogical split between power in ancient and Medieval

society and late modern society, such as our own. By split Foucault

means power as a force for manipulation of the human body. Previous

notions of power failed to account for the historical subject and

general shifts in techniques of power-according to Foucault's genealogy

or genesis of power – it was totally denied that manipulation of the

human body by unforeseen, outside forces ever existed. According to this

theory, it was human ingenuity and man's ability to increase his own

rationalisation was the primary motion behind social phenomena and the

human subject and change was a result of increasing human reason and

human conscience ingenuity. Foucault denies that any such notion had

ever existed in the historical record and insists that this kind of

thought is a misleading abstraction. Foucault cites the main driving

force behind this set of accelerated change was the modern human

sciences and the technologies both available to skilled professionals

from the 16th century and a whole set of clever techniques used to shift

the whole old social order into the new order of things. However, what

was significant was the notion of Population

practised upon the entire human species on a global mass scale, not in

separately locally defined areas. By population, Foucault means its

fluidness and malleability, Foucault refers to 'a multiplicity of men,

not to the extent that they are nothing more than individual bodies, but

to the extent that they form, on the contrary, a global mass that is

affected by overall processes of birth, death, production, taxation,

illness and so forth, one should also take note that Foucault does not

just mean population as singular event but a means of circulation tied

to factors of security. What again was also significant was the idea of

"freedom" the population's "freedom" which was the new modern Nation state and the 'neo-discourse' erected around such notions as freedom, work and Liberalism,

the ideological stance of the state (mass popular democracy and the

voting franchise) and the state was only too willing to recognize and

give freedom for example as the object of security. Population, in

Foucault's understanding, is understood as a self-regulating mass;an

agglomeration or circulation of people and things which co-operate and

co-produce order free from heavy state regulation the state governs less

allowing the population to "govern itself". For Foucault, the freedom

of population is grasped at the level of how elements of population

circulate. Techniques of security enact themselves through, and upon,

the circulation which occurs at the level of population. In Foucault's

opinion the modern concept of population, as opposed to the ancient Antiquity and medieval version of "populousness" which has in its roots going as far back as the time period of the Book of Numbers in the Old Testament Bible

and the work that it sustained both in political theory and practice

certainly does so; or, at least, the construction of the concept

population is central to the creation of new orders of knowledge, new

objects of intervention, new forms of subjectivity.

However, in order to fully understand what Foucault is trying to

convey a few things should be said about the alteration techniques used

that Foucault talks about in this series of lectures. The ancient and

medieval version of Political power was centered around a central figure who was called a King, Emperor, Prince or ruler (and in some cases the pope) of his principle territory whose rule was considered absolute (Absolute monarchy) by both Political philosophy

and political theory of the day even in our time such notions still

exist. Foucault uses the term population state to designate a new

founded technology founded on the principal of security and territory

which would mean a "population" to govern on a global mass with each

population having its own territorial integrity(a separate nation)

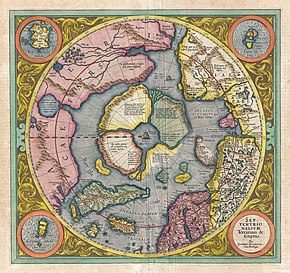

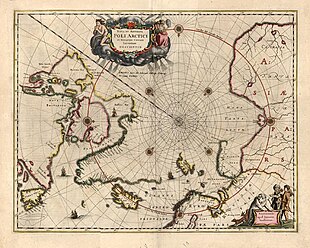

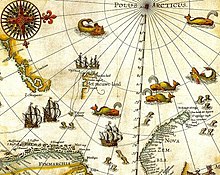

mapped out by experts in treaty negotiations and the new emerging field of 15th century Advances in map-making technologies and the profession of Cartography eventually producing in the 18th century what we now know as nation states.

These technologies take place at the level of "population" Foucault

argues, and with the shifting aside of the body of the King or

territorial ruler. By the time of the ending of the medieval period the

body(or the persona of the king)of the territorial ruler became under

increasingly under financial pressure and a cursory look at the medieval

financial records tends to show that the monarch could not pay back all

debts due to his creditors; the monarch would easily and readily

default on loans due to any creditors causing financial ruin to

creditors. Foucault notices that by the time of the 18th century several

changes began to take place like the re-organization of armies, an

emerging industrial working population begins to appear, (both military

and industrial), the emergence of the Mathematical sciences, Biological sciences and Physical sciences

which, coincidently gave birth to a-what Foucault calls-Biopower and a

political apparatus (machine) to take care of biological (in the form of

medicine and health) and political life (mass democracy and the voting

franchise for the population). An apparatus (both economic and

political) was required much more sophisticated than previous social

organisations of previous societies had at their disposal. For example, Banks,

which function as financial intermediaries and tied to the apparatus of

the new 'state' machine which can easily pay back any large scale debts

(large debts) which the King cannot, due to the king's own financial

resources are limited;the king cannot pay back for example, the national

debt, nor pay for a modern army out of his own personal resources,

which can amount to trillions of US Dollars out of his own personal

finances, that would be both impracticable and impossible.

The Birth of Biopolitics (1978–1979)

The Birth of Biopolitics develops further the notion of biopolitics

that Foucault introduced in his lectures on "Society must be defended".

It traces how eighteenth-century political economy marked the birth of a

new governmental rationality and raises questions of political

philosophy and social policy about the role and status of neo-liberalism

in twentieth century politics.

Over the course of many centuries the association between

biological phenomena and human political behaviour has received a great

deal of attention. Recently (the last 60 years or so) in the academic

field and journals there has been some development within the field of

political and biological behaviour. In his College de France lecture

course of January 1978 Foucault use the term Biopolitics (not for the

first time) to denote politic power over every aspect of human life. Why

did Foucault use the term 'biopolitics' in the first place? First of

all the term has many different meanings to many different people and to

fully understand the term as Foucault saw and used and understood it,

we have to look at the very different meanings of the concept. For

Foucault the term means to him the association between biological

phenomena and human political behaviour maximizing and increasing the

human abilities machine (as we know the term). Over the course of

evolutionary time this abilities machine of man becomes species

specific, such as language capabilities, neuronal and cognitive

capabilities so on and so forth. This then becomes over the course of

the history of discursive technologies of scientific knowledge, Foucault

argues, a field of knowledge established by groups of experts in

disciplines, such as astronomy, biology, chemistry, geoscience, physics, anthropology, archaeology, linguistics, psychology, sociology, and history, for example.

The study of a new and rigorous discipline allied together with a

new language (discourse technologies) in which a grasp of the new

language is needed developing into a powerful force in the political

realm as well as biological evolution the two become powerful allies

(both biology and politics). Genetics and the change that develops (over

time) over the course of the human organism existence. However, the two

become co-joined unwittingly but one of them both political philosophy

and political science have specific problems, both cannot have or lay

claim to independent knowledge which is problematic for both lines of

thought. Not in the case of ideology (as in Marxism) but in the case of

discursive technologies. Foucault insists that the scientific knowledge

being presented by historians is not an endeavour by the whole of

humankind, particularly when written about by historians who claim that

'man' invented the sciences anymore than the Nazi represented the whole

of humankind and the whole of humankind were to blame for the Nazi

atrocities the ultimate embodiment of evil. But is, for all attempts and

purposes a collaborative enterprise by groups of specially trained

specialists producing a scientific community who have unfettered access

to the whole of society through their scientific knowledge and

expertise.

Change does indeed happen both within the organism and the

organisms properties, the specific species is unable to correct them

directly and biological change moves beyond any individual or single

member of the species. However, these changes are aimed at the species

as a whole and characteristics and traits are retained both at the

biological, ecological and environmental level. In the human sciences

(biology and genetics) these changes happen at a genetic and biological

level which are unalterable and transpire from one generation to the

next not at the individual level of the species. This is at the heart of

the core theory of Charles Darwin and his proponents and the theory of Evolution and natural selection.

Foucault's analysis try's to show that contrary to previous thought

that the modern human sciences were somehow an obscure universal

objective source which somehow had an absence of any lineage, took over

the role of the Christian church in disciplining the body by replacing

the soul and confession of the Catholic church plus also the specific

director of the process which in this case would be the deity (God),

with indefinite supervision and discipline. However, these new

techniques required a new 'director(s)' or 'editor(s)' who replaced the

priestly and Pharaonic

versions of much similar past vintages. These new governmental

mechanism based upon the right of sovereignty and law both supported the

fixed hierarchical organisation of the previous mode of feudal

governmental mechanism, but stripping the modern human subject of any

kind of self autonomy; not only fully fit for indoctrination, work, and

education a fully fit conversant subject but left them vulnerable as

well to face a permanent exam which he(the ordinary individual) had no

chance in passing and was supposed to fail with no end point. Foucault

maintains that these techniques were deliberate, cold, calculating and

ruthless; the human sciences, far from being "a way at looking at the

world" the knowledge/power dynamic/relationship Paradigm

was a 'cheap' efficient and 'cost' effective method into a way of

producing a subjugated and docile human subject (not only a citizen, but

a political and productive citizen) as an instrument for administrative

control and concern (through the state) for the well being of the

population(and a constant help to the spread of biopower) with the help

of scientific classifications and new disciplinary technologies

including the polity readily available to the human body and mind. Here

are a few examples on what Foucault means by this type of "biopower" and

bio-history of man

Elizabeth Loftus

is well known for her research in the area of memory. In this book she

examines the way memories are encoded and the varies ways they can be

altered. Forensic psychologists are frequently called upon to assess the

veracity of an eyewitness testimony. Loftus makes a strong argument

against the eyewitness with a multitude of studies that have

demonstrated the unreliability of their reports. New memories can be

implanted and old memories altered with ease and this renders memories

susceptible to tampering. The manner in which a question is posed can

alter or implant a memory. The multiple choice style versus the

open-ended style of questions are examples of this. The latter allows

the witness to respond with "I don't know" whereas the former demands a

response Loftus has found that people unknowingly convince themselves of

an answer when forced to give an answer. With numerous real-life

examples that address how we retain and retrieve memories to the

differences in eyewitness ability, this book is vital to the

understanding of Forensic psychology.

"Yochelson and Samenow in this three volume series examine the

criminal personality. The series starts at the first encounter with the

offender and continues through to the process of change. It includes the

issue of drug use in this population. The authors have detailed their

research with what they termed "the criminal mind."Their definition of

the criminal strongly resembles the description of

antisocial-personality disorder and psychopathy. During the early stages

of their research, Yochelson and Samenow limited their work to

observation without the attempt of treatment. They detailed 52 features

of criminal thinking that needed to be changed for rehabilitation to be a

possibility. Patterns of deception are established early in this

population and others rights are characteristically disregarded, and

when arrested, this population tends to see themselves as victims and

believe that they were good people despite their lengthy criminal

records. Over time a treatment plan, or "process of change" was defined

that change was most likely to occur in this population when the

individual was vulnerable and desirous of change. The desire for change

must be accompanied by an in depth knowledge of what needs to be

changed. Finally, change is only possible when the long term benefits of

change outweigh the benefits of maintaining a criminal lifestyle.

Overall, change is considered a possibility, although not a common one.

These three volumes comprise the most detailed, long-term examination of

the criminal mind documented."

"Linguists have testified in legal cases implicating a wide range of linguistic levels, e.g.phonetics, phonology, morphology,syntax,

semantics, pragmatics, and variations. Legal issues have included the

following:statuary and contract language ambiguity; comprehensibility of

jury instructions problems with verbatim transcripts;spoken language as

evidence of intent;adequacy of warning labels on consumer

products;verbal offences (libel, slander);compliance with plain language

requirements;trademark and copyright infrigement;informed consent;and

the regulation of advertising language by the Federal Trade Commission

in the US. The best known and most experienced forensic linguist in

North America is Roger Shuy whose name was for a number of years synonymous with Forensic linguistics in the case of trial consultant/expert.

As with the most recent discovery of mirror neurons has demonstrated Foucault has (while these techniques used in Psychiatry and Psychology

are not mentioned alongside Foucault's name) hit on something that

rigorous research methods may prove beyond a reasonable doubt that

manipulation of social phenomena(which includes the human body and the

mind) is most certainly possible. Techniques developed from the First

and Second World war which started out as field experiments, among

military personnel, were then extended into ordinary civilian life;

techniques borrowed from the Human cognitive sciences and found its way

into Psycho-analysis, Psychiatry, Psychology, Clinical psychology, Lightner Witmer and Clinical psychiatry (see this encyclopedia's article on Political abuse of psychiatry):"Mobilisation and manipulation of human needs as they exist in the consumer". He (Ernest Dichter) "was the first to coin the term focus group and to stress the importance of image and persuasion in advertising". In Vance Packard's book, The Hidden Persuaders

Dichter's name is mentioned extensively. Subjectivation, a term

Foucault coined for this purpose in which Biological life itself is

given over to constant testing and research(an examination) without ever

ending. One could argue;who are these new experts answerable

too?Foucault argues that these new experts are answerable to absolutely

no one. Just like previous notions of the past, absolute monarchy and

divine rights of kings were answerable to nobody, their predecessors are

just replacements of the past these new experts have now been

democratised. Where mans body (and his soul)his mind can be manipulated

and altered and is liable to be vulnerable. Every single aspect of the

human subject is ripe for 'subjectification' and the technology-as it stands today-is unknown to us. This Biological allegory of man carries with it endless possibilities from the perspective of the Biological sciences and Physical sciences.

The above extractions clearly show this "Biopower" of man requires man

himself to administer these sophisticated technologies, where one group

of experts or professionals(the enquiry) can completely subjugate

another producing new human subjects(and new experts) through their

expertise at manipulating social phenomena. In these few examples and

according to this view:"the criminal is treated like a cancer" whereas

human nature does not change which is the only society that ever gets

produced, past, present or future.

On The Government Of The Living (1979–1980)

In the On The Government Of The Living lectures delivered in

the early months of 1980, Foucault begins to ask questions of Western

man obedience to power structures unreservedly and the pressing question

of Government: "Government of children, government of souls and

consciences, government of a household, of a state, or of oneself." Or governmentality,

as Foucault prefers to call it, although he fleshes out the development

of that concept in his earlier lectures titled "Security, Territory,

Population." Foucault tries to trace the kernel of "the genealogy of

obedience" in western society. The 1980 lectures attempt to relate the

historical foundations of "our obedience"—which must be understood as

the obedience of the Western subject. Foucault argues confessional

techniques are an innovation of the Christian West intended to guarantee

men's obedience to structures of power in return, so the belief goes,

for Christian salvation. In his summary of the course Foucault asks the

question: "How is it that within Western Christian culture, the

government of men requires, on the part of those who are led, in

addition to acts of obedience and submission, 'acts of truth,' which

have this particular character that not only is the subject required to

speak truthfully but to speak truthfully about himself?" The reader

should take note here that much of this kind of work has been done

before, albeit in what is best described as brilliant, lost and

forgotten scholarship by such scholars as Ernst Kantorowicz (his work on the body politic and the king's two bodies), Percy Ernst Schramm, Carl Erdmann, Hermann Kantorowicz, Frederick Pollock and Frederick Maitland.

However, Foucault was after the genealogical dynamics and his main

thrust was "regimes of truth" and the emergence and gradual development

of "reflexive acts of truth". Foucault locates the very beginning of

this act of obedience to power structures and the truth that they bring

to the first Christian institutions between the 2nd century and the 5th

century C.E. This is where Foucault starts to use his main tool—that is Genealogy

as his main focus and it is with this genealogical tool that you

finally get to understand fully what genealogy actually means. Foucault

goes into great painstaking detail into the Christian baptism

and its contingency and discontinuity in order to find "the genealogy

of confession". This is an attempt—argues Foucault—to write a "political

history of the truth".

Subjectivity and Truth (1980–1981)

In Subjectivity and Truth,

Foucault undertakes a deep analysis of sexuality, sexual ethics, and

marriage. He looks at the evolving concept of relationships, marriage,

and spouses as historical constructs.

The Hermeneutics of the Subject (1981–1982)

In

these lectures, Foucault develops notions on the ability of the concept

of truth to shift through time as described by the modern human

sciences (for example ethnology)

in contrast to ancient society (Aristotelian notions). It discusses how

these notions are accepted as truth and produce the self as true. This

is followed by a discussion on the existence of this truth and the

discourse of truth for the experience of the self.

The Government of Self and Others (1982–1983)

The

final two years of lectures deal with the concept of parrhesia,

translated by Foucault as 'frank speech' and the relationship between

the political and the self.

The Courage of Truth (1983–1984)

The last course Foucault gave at the Collège de France was delayed by illness, for which Foucault received treatment in January 1984.

The lectures were ultimately delivered over nine consecutive Wednesdays

in February and March of that year. In several of the lectures,

Foucault complains of suffering from a bad flu and apologizes for his

diminished strength. Although relatively little was known about AIDS at the time, there are several indications that Foucault already suspected he had contracted the virus.

The content of the course expands on the analysis of parrhesia

Foucault developed during the previous year, with renewed focus on

Plato, Socrates, Cynicism, and Stoicism. On February 15, Foucault

delivered a moving lecture on the death of Socrates and the meaning of Socrates' last words.

On March 28, twelve weeks before he succumbed to AIDS-related

complications, Foucault delivered his final lecture. His last words at

the lectern were:

...Only by deciphering the truth of self in this world, deciphering

oneself with mistrust of oneself and the world, and in fear and

trembling before God, will enable us to have access to the true life. It

was by this reversal, which put the truth of life before the true life

that Christian asceticism fundamentally modified an ancient asceticism

which always aspired to lead both the true life and the life of truth at

the same time, and which, in Cynicism at least, affirmed the

possibility of leading this true life of truth.

There you are, listen, I had things to say to you about the

general framework of these analyses. But, well, it is too late. So,

thank you.