A weapon, arm, or armament is any implement or device that is used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime (e.g., murder), law enforcement, self-defense, warfare, or suicide. In a broader context, weapons may be construed to include anything used to gain a tactical, strategic, material, or mental advantage over an adversary or enemy target.

While ordinary objects such as rocks and bottles can be used as weapons, many objects are expressly designed for the purpose; these range from simple implements such as clubs and swords to complicated modern firearms, tanks, missiles and biological weapons. Something that has been repurposed, converted, or enhanced to become a weapon of war is termed weaponized, such as a weaponized virus or weaponized laser.

History

The use of weapons has been a major driver of cultural evolution and human history up to today since weapons are a type of tool that is used to dominate and subdue autonomous agents such as animals and, by doing so, allow for an expansion of the cultural niche, while simultaneously other weapon users (i.e., agents such as humans, groups, and cultures) are able to adapt to the weapons of enemies by learning, triggering a continuous process of competitive technological, skill, and cognitive improvement (arms race).

Prehistoric

The use of objects as weapons has been observed among chimpanzees, leading to speculation that early hominids used weapons as early as five million years ago. However, this cannot be confirmed using physical evidence because wooden clubs, spears, and unshaped stones would have left an ambiguous record. The earliest unambiguous weapons to be found are the Schöningen spears, eight wooden throwing spears dating back more than 300,000 years. At the site of Nataruk in Turkana, Kenya, numerous human skeletons dating to 10,000 years ago may present evidence of traumatic injuries to the head, neck, ribs, knees, and hands, including obsidian projectiles embedded in the bones that might have been caused by arrows and clubs during conflict between two hunter-gatherer groups. But the interpretation of warfare at Nataruk has been challenged due to conflicting evidence.

Ancient history

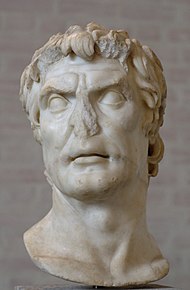

The earliest ancient weapons were evolutionary improvements of late Neolithic implements, but significant improvements in materials and crafting techniques led to a series of revolutions in military technology.

The development of metal tools began with copper during the Copper Age (about 3,300 BC) and was followed by the Bronze Age, leading to the creation of the Bronze Age sword and similar weapons.

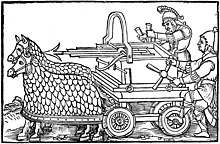

During the Bronze Age, the first defensive structures and fortifications appeared as well, indicating an increased need for security. Weapons designed to breach fortifications followed soon after, such as the battering ram, which was in use by 2500 BC.

The development of ironworking around 1300 BC in Greece had an important impact on the development of ancient weapons. It was not the introduction of early Iron Age swords, however, as they were not superior to their bronze predecessors, but rather the domestication of the horse and widespread use of spoked wheels by c. 2000 BC. This led to the creation of the light, horse-drawn chariot, whose improved mobility proved important during this era. Spoke-wheeled chariot usage peaked around 1300 BC and then declined, ceasing to be militarily relevant by the 4th century BC.

Cavalry developed once horses were bred to support the weight of a human. The horse extended the range and increased the speed of attacks. Alexander's conquest saw the increased use of spears and shields in the Middle East and Western Asia as a result Greek culture spread which saw many Greek and other European weapons be used in these regions and as a result many of these weapons were adapted to fit their new use in war.

In addition to land-based weaponry, warships, such as the trireme, were in use by the 7th century BC. During the first First Punic War, the use of advanced warships contributed to a Roman victory over the Carthaginians.

Post-classical history

European warfare during post-classical history was dominated by elite groups of knights supported by massed infantry. They were involved in mobile combat and sieges, which involved various siege weapons and tactics. Knights on horseback developed tactics for charging with lances, providing an impact on the enemy formations, and then drawing more practical weapons (such as swords) once they entered melee. By contrast, infantry, in the age before structured formations, relied on cheap, sturdy weapons such as spears and billhooks in close combat and bows from a distance. As armies became more professional, their equipment was standardized, and infantry transitioned to pikes. Pikes are normally seven to eight feet in length and used in conjunction with smaller sidearms (short swords).

In Eastern and Middle Eastern warfare, similar tactics were developed independent of European influences.

The introduction of gunpowder from Asia at the end of this period revolutionized warfare. Formations of musketeers, protected by pikemen, came to dominate open battles, and the cannon replaced the trebuchet as the dominant siege weapon. The Ottoman used the cannon to destroy much of the fortifications at Constantinople which would change warfare as gunpowder became more available and technology improved

Modern history

Early modern

The European Renaissance marked the beginning of the implementation of firearms in western warfare. Guns and rockets were introduced to the battlefield.

Firearms are qualitatively different from earlier weapons because they release energy from combustible propellants, such as gunpowder, rather than from a counterweight or spring. This energy is released very rapidly and can be replicated without much effort by the user. Therefore, even early firearms such as the arquebus were much more powerful than human-powered weapons. Firearms became increasingly important and effective during the 16th–19th centuries, with progressive improvements in ignition mechanisms followed by revolutionary changes in ammunition handling and propellant. During the American Civil War, new applications of firearms, including the machine gun and ironclad warship, emerged that would still be recognizable and useful military weapons today, particularly in limited conflicts. In the 19th century, warship propulsion changed from sail power to fossil fuel-powered steam engines.

Since the mid-18th century North American French-Indian war through the beginning of the 20th century, human-powered weapons were reduced from the primary weaponry of the battlefield to yielding gunpowder-based weaponry. Sometimes referred to as the "Age of Rifles", this period was characterized by the development of firearms for infantry and cannons for support, as well as the beginnings of mechanized weapons such as the machine gun. Artillery pieces such as howitzers were able to destroy masonry fortresses and other fortifications, and this single invention caused a revolution in military affairs, establishing tactics and doctrine that are still in use today.

World War I

An important feature of industrial age warfare was technological escalation – innovations were rapidly matched through replication or countered by another innovation.

World War I marked the entry of fully industrialized warfare as well as weapons of mass destruction (e.g., chemical and biological weapons), and new weapons were developed quickly to meet wartime needs. The technological escalation during World War I was profound, including the wide introduction of aircraft into warfare and naval warfare with the introduction of aircraft carriers. Above all, it promised the military commanders independence from horses and a resurgence in maneuver warfare through the extensive use of motor vehicles. The changes that these military technologies underwent were evolutionary but defined their development for the rest of the century.[This paragraph needs citation(s)]

Interwar

This period of innovation in weapon design continued in the interwar period (between WWI and WWII) with the continuous evolution of weapon systems by all major industrial powers. The major armament firms were Schneider-Creusot (based in France), Škoda Works (Czechoslovakia), and Vickers (Great Britain). The 1920s were committed to disarmament and the outlawing of war and poison gas, but rearmament picked up rapidly in the 1930s. The munitions makers responded nimbly to the rapidly shifting strategic and economic landscape. The main purchasers of munitions from the big three companies were Romania, Yugoslavia, Greece, and Turkey – and, to a lesser extent, Poland, Finland, the Baltic States, and the Soviet Union.

Criminalizing poison gas

Realistic critics understood that war could not really be outlawed, but its worst excesses might be banned. Poison gas became the focus of a worldwide crusade in the 1920s. Poison gas did not win battles, and the generals did not want it. The soldiers hated it far more intensely than bullets or explosive shells. By 1918, chemical shells made up 35 percent of French ammunition supplies, 25 percent of British, and 20 percent of American stock. The "Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous, or Other Gases and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare", also known as the Geneva Protocol, was issued in 1925 and was accepted as policy by all major countries. In 1937, poison gas was manufactured in large quantities but not used except against nations that lacked modern weapons or gas masks.

World War II and postwar

Many modern military weapons, particularly ground-based ones, are relatively minor improvements to weapon systems developed during World War II. World War II marked perhaps the most frantic period of weapon development in the history of humanity. Massive numbers of new designs and concepts were fielded, and all existing technologies were improved between 1939 and 1945. The most powerful weapon invented during this period was the nuclear bomb; however, many other weapons influenced the world, such as jet aircraft and radar, but were overshadowed by the visibility of nuclear weapons and long-range rockets.

Nuclear weapons

Since the realization of mutual assured destruction (MAD), the nuclear option of all-out war is no longer considered a survivable scenario. During the Cold War in the years following World War II, both the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a nuclear arms race. Each country and their allies continually attempted to out-develop each other in the field of nuclear armaments. Once the joint technological capabilities reached the point of being able to ensure the destruction of the Earth by 100 fold, a new tactic had to be developed. With this realization, armaments development funding shifted back to primarily sponsoring the development of conventional arms technologies for support of limited wars rather than total war.

Types

By user

- – what person or unit uses the weapon

- Personal weapons (or small arms) – designed to be used by a single person.

- Light weapons – 'man-portable' weapons that may require a small team to operate.

- Heavy weapons – artillery and similar weapons larger than light weapons (see SALW).

- Crew served weapons – larger than personal weapons, requiring two or more people to operate correctly.

- Fortification weapons – mounted in a permanent installation or used primarily within a fortification.

- Mountain weapons – for use by mountain forces or those operating in difficult terrain.

- Vehicle-mounted weapons – to be mounted on any type of combat vehicle.

- Railway weapons – designed to be mounted on railway cars, including armored trains.

- Aircraft weapons – carried on and used by some type of aircraft, helicopter, or other aerial vehicle.

- Naval weapons – mounted on ships and submarines.

- Space weapons – are designed to be used in or launched from space.

- Autonomous weapons – are capable of accomplishing a mission with limited or no human intervention.

By function

- – the construction of the weapon and the principle of operation

- Antimatter weapons (theoretical) – would combine matter and antimatter to cause a powerful explosion.

- Archery weapons – operate by using a tensioned string and a bent solid to launch a projectile.

- Artillery – firearms capable of launching heavy projectiles over long distances.

- Biological weapons – spread biological agents, causing disease or infection.

- Blunt instruments – designed to break or fracture bones, produce concussions, create organ ruptures, or crush injuries.

- Chemical weapons – poison people and cause reactions.

- Edged and bladed weapons – designed to pierce or cut through skin, muscle, or bone and cause internal or external bleeding.

- Energy weapons – rely on concentrating forms of energy to attack, such as lasers or sonic attacks.

- Explosive weapons – use a physical explosion to create a blast, concussion, or spread shrapnel.

- Firearms – use a chemical charge to launch projectiles.

- Improvised weapons – common objects reused as weapons, such as crowbars and kitchen knives.

- Incendiary weapons – cause damage by fire.

- Loitering munitions – designed to loiter over a battlefield, striking once a target is located.

- Magnetic weapons – use magnetic fields to propel projectiles or focus particle beams.

- Missiles – rockets that are guided to their target after launch. (Also a general term for projectile weapons.)

- Non-lethal weapons – designed to subdue without killing.

- Nuclear weapons – use radioactive materials to create nuclear fission or nuclear fusion detonations

- Rockets – self-propelled projectiles.

- Suicide weapons – exploit the willingness of their operators not surviving the attack.

By target

- – the type of target the weapon is designed to attack

- Anti-aircraft weapons – target missiles and aerial vehicles in flight.

- Anti-fortification weapons – designed to target enemy installations.

- Anti-personnel weapons – designed to attack people, either individually or in numbers.

- Anti-radiation weapons – target sources of electronic radiation, particularly radar emitters.

- Anti-satellite weapons – target orbiting satellites.

- Anti-ship weapons – target ships and vessels on water.

- Anti-submarine weapons – target submarines and other underwater targets.

- Anti-tank weapons – designed to defeat armored targets.

- Area denial weapons – target territory, making it unsafe or unsuitable for enemy use or travel.

- Hunting weapons – weapons used to hunt game animals.

- Infantry support weapons – designed to attack various threats to infantry units.

- Siege engines – designed to break or circumvent heavy fortifications in siege warfare.

Manufacture of weapons

The arms industry is a global industry that involves the sale and manufacture of weaponry. It consists of a commercial industry involved in the research and development, engineering, production, and servicing of military material, equipment, and facilities. Many industrialized countries have a domestic arms industry to supply their own military forces, and some also have a substantial trade in weapons for use by their citizens for self-defense, hunting, or sporting purposes.

Contracts to supply a given country's military are awarded by governments, making arms contracts of substantial political importance. The link between politics and the arms trade can result in the development of a "military–industrial complex", where the armed forces, commerce, and politics become closely linked.

According to research institute SIPRI, the volume of international transfers of major weapons in 2010–2014 was 16 percent higher than in 2005–2009, and the arms sales of the world's 100 largest private arms-producing and military services companies totaled $420 billion in 2018.

Legislation

The production, possession, trade, and use of many weapons are controlled. This may be at a local or central government level or by international treaty. Examples of such controls include:

Gun laws

All countries have laws and policies regulating aspects such as the manufacture, sale, transfer, possession, modification, and use of small arms by civilians.

Countries that regulate access to firearms will typically restrict access to certain categories of firearms and then restrict the categories of persons who may be granted a license for access to such firearms. There may be separate licenses for hunting, sport shooting (a.k.a. target shooting), self-defense, collecting, and concealed carry, with different sets of requirements, permissions, and responsibilities.

Arms control laws

International treaties and agreements place restrictions on the development, production, stockpiling, proliferation, and usage of weapons, from small arms and heavy weapons to weapons of mass destruction. Arms control is typically exercised through the use of diplomacy, which seeks to impose such limitations upon consenting participants, although it may also comprise efforts by a nation or group of nations to enforce limitations upon a non-consenting country.

Arms trafficking laws

Arms trafficking is the trafficking of contraband weapons and ammunition. What constitutes legal trade in firearms varies widely, depending on local and national laws. In 2001, the United Nations had made a protocol against the manufacturing and trafficking of illicit arms. This protocol made governments dispose illegal arms, and to licence new firearms being produced, to ensure them being legitimate. It was signed by 122 parties.

Lifecycle problems

There are a number of issues around the potential ongoing risks from deployed weapons, the safe storage of weapons, and their eventual disposal when they are no longer effective or safe.

- Ocean dumping of unused weapons such as bombs, ordnance, landmines, and chemical weapons has been common practice by many nations and has created hazards.

- Unexploded ordnance (UXO) are bombs, land mines, naval mines, and similar devices that did not explode when they were employed and still pose a risk for many years or decades.

- Demining or mine clearance from areas of past conflict is a difficult process, but every year, landmines kill 15,000 to 20,000 people and severely maim countless more.

- Nuclear terrorism was a serious concern after the fall of the Soviet Union, with the prospect of "loose nukes" being available. While this risk may have receded, similar situations may arise in the future.

In science fiction

Strange and exotic weapons are a recurring feature or theme in science fiction. In some cases, weapons first introduced in science fiction have now become a reality. Other science fiction weapons, such as force fields and stasis fields, remain purely fictional and are often beyond the realms of known physical possibility.

At its most prosaic, science fiction features an endless variety of sidearms, mostly variations on real weapons such as guns and swords. Among the best-known of these are the phaser used in the Star Trek television series, films, and novels, and the lightsaber and blaster featured in the Star Wars movies, comics, novels, and TV series.

In addition to adding action and entertainment value, weaponry in science fiction sometimes becomes a theme when it touches on deeper concerns, often motivated by contemporary issues. One example is science fiction that deals with weapons of mass destruction like doomsday devices.