Biblical archaeology is an academic school and a subset of Biblical studies and Levantine archaeology. Biblical archaeology studies archaeological sites from the Ancient Near East and especially the Holy Land (also known as Land of Israel and Canaan), from biblical times.

Biblical archaeology emerged in the late 19th century, by British and American archaeologists, with the aim of confirming the historicity of the Bible. Between the 1920s, right after World War I, when Palestine came under British rule and the 1960s, biblical archaeology became the dominant American school of Levantine archaeology, led by figures such as William F. Albright and G. Ernest Wright. The work was mostly funded by churches and headed by theologians. From the late 1960s, biblical archaeology was influenced by processual archaeology ("New Archaeology") and faced issues that made it push aside the religious aspects of the research. This has led the American schools to shift away from biblical studies and focus on the archaeology of the region and its relation with the biblical text, rather than trying to prove or disprove the biblical account.

The Hebrew Bible is the main source of information about the region of Palestine and mostly covers the Iron Age period. Therefore, archaeology can provide insights where biblical historiography is unable to. The comparative study of the biblical text and archaeological discoveries help understand Ancient Near Eastern people and cultures. Although both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament are taken into account, the majority of the study centers around the former.

The term biblical archaeology is used by Israeli archaeologists for popular media or an English speaking audience, in reference to what is known in Hebrew as "Israeli archaeology", and to avoid using the term Palestinian archaeology.

History

The study of biblical archaeology started at the same time as general archaeology, the development of which relates to the discovery of highly important ancient artifacts.

Stages

The development of biblical archaeology has been marked by different periods;

- Before the British Mandate in Palestine: The first archaeological explorations started in the 19th century initially by Europeans. There were many renowned archaeologists working at this time, one of the best known being Edward Robinson, who discovered a number of ancient cities. The Palestine Exploration Fund was created in 1865 with Queen Victoria as its patron. Large investigations were carried out around the Temple in Jerusalem in 1867 by Charles Warren and Charles William Wilson, after whom Jerusalem's "Wilson’s Arch" is named. The American Palestine Exploration Society was founded in 1870. In the same year, a young French archaeologist, Charles Clermont-Ganneau, arrived in the Holy Land in order to study two notable inscriptions: the Mesha Stele in Jordan and inscriptions in the Temple of Jerusalem. Another personality entered the scene in 1890, Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, who has since become known as the "father of Palestine archaeology". In Tell-el-Hesi, Petrie laid down the basis for methodical exploration by giving a great importance to the analysis of ceramics as archaeological markers. In effect, the recovered objects or fragments serve to fix the chronology with a degree of precision, as pottery was made in different ways and with specific characteristics during each epoch throughout history. In 1889, the Dominican Order opened the French Biblical and Archaeological School of Jerusalem, which would become world-renowned in its field. Such authorities as M-J. Lagrange and L. H. Vincent stand out among the early archaeologists at the school. In 1898, the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (German Oriental Society) was founded in Berlin, a number of its excavations were subsequently funded by Emperor William II of Germany. Many other similar organizations were founded at this time with the objective of furthering this nascent discipline, although the investigations of this epoch had the sole objective of proving the veracity of the biblical stories.

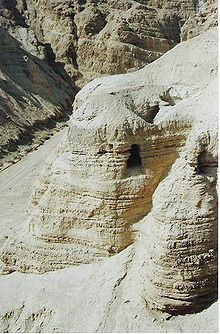

- During the British Mandate in Palestine (1922–1948): The investigation and exploration of the Holy Land increased considerably during this time and was dominated by the genius of William Foxwell Albright, C. S. Fischer, the Jesuits, the Dominicans and many others. This era of great advances and activity closed with a flourish: the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran in 1947 and its subsequent excavation, which would in large part be directed by the Frenchman Roland de Vaux.

- After the British Mandate: 1948 marked the start of a new social and political era for the Holy Land, with the foundation of the State of Israel and the entrance on the scene of the Israeli archaeologists. Initially their excavations were limited to the territory of the state, but after the Six-Day War they extended into the occupied territories of the West Bank. An important figure in the archaeology of this period was Kathleen Kenyon, who directed the excavations of Jericho and the Ophel of Jerusalem. Crystal Bennett led the excavations at Petra and Amman’s citadel, Jabal al-Qal'a. The archaeological museums of the Franciscans and the Dominicans in Jerusalem are particularly notable.

- Biblical archaeology today: Twenty-first century biblical archaeology is often conducted by international teams sponsored by universities and government institutions such as the Israel Antiquities Authority. Volunteers are recruited to participate in excavations conducted by a staff of professionals. Practitioners are making increasing efforts to relate the results of one excavation to others nearby in an attempt to create an ever-widening, increasingly detailed overview of the ancient history and culture of each region. Recent rapid advances in technology have facilitated more scientifically precise measurements in dozens of related fields, as well as more timely and more broadly disseminated reports.

Schools of thought

Biblical archaeology is the subject of ongoing debate. One of the sources of greatest dispute is the period when kings ruled Israel, more generally the historicity of the Bible. It is possible to define two loose schools of thought regarding these areas: biblical minimalism and maximalism, depending on whether the Bible is considered to be a non-historical, religious document or not. The two schools are not separate units but form a continuum, making it difficult to define different camps and limits. However, it is possible to define points of difference, although these differences seem to be decreasing over time.

Summary of important archaeological sites and findings

Selected discoveries

Detailed lists of objects can be found at the following pages:

- List of inscriptions in biblical archaeology

- List of burial places of Abrahamic figures

- List of Hebrew Bible manuscripts, List of New Testament papyri and List of New Testament uncials

- List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sources

Biblical archeological forgeries

Biblical archaeology has also been the target of several celebrated forgeries, which have been perpetrated for a variety of reasons. One of the most celebrated is that of the James Ossuary, when information came to light in 2002 regarding the discovery of an ossuary, with an inscription that translated to "Jacob, son of Joseph and brother of Jesus". In reality the artifact had been discovered twenty years before, after which it had exchanged hands a number of times and the inscription had been added. This was discovered because it did not correspond to the pattern of the epoch from which it dated.

The object came by way of the antiques dealer Oded Golan, who was accused by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) of forgery, but after a 7-year trial he was acquitted on the grounds of reasonable doubt. Another item that came from the same dealer was the Jehoash Inscription, which describes repairs to the temple in Jerusalem. The authenticity of the inscription is debated.

Biblical archaeology and the Catholic Church

There are some groups that take a more fundamentalist approach and which organize archaeological campaigns with the intention of finding proof that the Bible is factual and that its narratives should be understood as historical events. This is not the official position of the Catholic Church.

Archaeological investigations carried out with scientific methods can offer useful data in fixing a chronology that helps to order the biblical stories. In certain cases these investigations can find the place where these narratives took place, while in other cases they can confirm the veracity of the stories. However, in other matters they can question events that have been taken as historical fact, providing arguments that show that certain stories are not historical narratives but belong to a different narrative genre.

In 1943, Pope Pius XII recommended that interpretations of the scripture take archaeological findings into account in order to discern the literary genres used.

[...] the interpreter must, as it were, go back wholly in spirit to those remote centuries of the East and with the aid of history, archaeology, ethnology, and other sciences, accurately determine what modes of writing, so to speak, the authors of that ancient period would be likely to use, and in fact did use. [...]Let those who cultivate biblical studies turn their attention with all due diligence towards this point and let them neglect none of those discoveries, whether in the domain of archaeology or in ancient history or literature, which serve to make better known the mentality of the ancient writers, as well as their manner and art of reasoning, narrating and writing.[...]

— Pius XII, Encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu, paragraphs 35 and 40

Since this time, archaeology has been considered to provide valuable assistance and as an indispensable tool of the biblical sciences.

Expert commentaries

[...]"the purpose of biblical archaeology is the clarification and illumination of the biblical text and content through archaeological investigation of the biblical world."

— written by J.K. Eakins in a 1977 essay published in Benchmarks in Time and Culture and quoted in his essay "Archaeology and the Bible, An Introduction".

Archaeologist William G. Dever contributed to the article on "Archaeology" in the Anchor Bible Dictionary. In the article, Dever reiterated his perceptions of the negative effects of the close relationship that has existed between Syro-Palestinian archaeology and biblical archaeology, which had caused the archaeologists working in the field, particularly the American archaeologists, to resist adoption of the new methods of processual archaeology. In addition, he considered that "underlying much scepticism in our own field [referring to the adaptation of the concepts and methods of a "new archaeology", one suspects the assumption (although unexpressed or even unconscious) that ancient Palestine, especially Israel during the biblical period, was unique, in some "superhistorical" way that was not governed by the normal principles of cultural evolution".

Dever found that Syro-Palestinian archaeology had been treated in American institutions as a sub-discipline of bible studies, where it was expected that American archaeologists would try to "provide valid historical evidence of episodes from the biblical tradition". According to Dever, "the most naïve [idea regarding Syro-Palestinian archaeology] is that the reason and purpose of "biblical archaeology" (and, by extrapolation, of Syro-Palestinian archaeology) is simply to elucidate facts regarding the Bible and the Holy Land".

Dever has also written that:

Archaeology certainly doesn't prove literal readings of the Bible...It calls them into question, and that's what bothers some people. Most people really think that archaeology is out there to prove the Bible. No archaeologist thinks so. [...] From the beginnings of what we call biblical archaeology, perhaps 150 years ago, scholars, mostly western scholars, have attempted to use archaeological data to prove the Bible. And for a long time it was thought to work. William Albright, the great father of our discipline, often spoke of the "archaeological revolution." Well, the revolution has come but not in the way that Albright thought. The truth of the matter today is that archaeology raises more questions about the historicity of the Hebrew Bible and even the New Testament than it provides answers, and that's very disturbing to some people.

Dever also wrote:

Archaeology as it is practiced today must be able to challenge, as well as confirm, the Bible stories. Some things described there really did happen, but others did not. The biblical narratives about Abraham, Moses, Joshua and Solomon probably reflect some historical memories of people and places, but the 'larger than life' portraits of the Bible are unrealistic and contradicted by the archaeological evidence.... I am not reading the Bible as Scripture... I am in fact not even a theist. My view all along—and especially in the recent books—is first that the biblical narratives are indeed 'stories,' often fictional and almost always propagandistic, but that here and there they contain some valid historical information...

Tel Aviv University archaeologist Ze'ev Herzog wrote the following in the Haaretz newspaper:

This is what archaeologists have learned from their excavations in the Land of Israel: the Israelites were never in Egypt, did not wander in the desert, did not conquer the land in a military campaign and did not pass it on to the 12 tribes of Israel. Perhaps even harder to swallow is that the united monarchy of David and Solomon, which is described by the Bible as a regional power, was at most a small tribal kingdom. And it will come as an unpleasant shock to many that the God of Israel, YHWH, had a female consort and that the early Israelite religion adopted monotheism only in the waning period of the monarchy and not at Mount Sinai.

Other scholars have argued that Asherah may have been a symbol or icon in the context of Yahwism rather than a deity in her own right, and her association with Yahweh does not necessarily indicate a polytheistic belief system.

Professor Israel Finkelstein told The Jerusalem Post that Jewish archaeologists have found no historical or archaeological evidence to back the biblical narrative on the Exodus, the Jews' wandering in Sinai or Joshua's conquest of Canaan. On the alleged Temple of Solomon, Finkelstein said that there is no archaeological evidence to prove it really existed. Professor Yoni Mizrahi, an independent archaeologist, agreed with Israel Finkelstein.

Regarding the Exodus of Israelites from Egypt, Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass said:

Really, it’s a myth,... This is my career as an archaeologist. I should tell them the truth. If the people are upset, that is not my problem.

Other scholars dispute these claims. In his 2001 book The Old Testament Documents: Are They Reliable and Relevant? Evangelical Old Testament scholar Walter Kaiser, Jr. included a chapter entitled, "Does Archaeology Help the Case for Reliability?". Kaiser states:

[T]he study of archaeology has helped illuminate the Bible by casting light on its historical and cultural location. With increasing clarity, the setting of the Bible appears more vividly within the framework of general history.... by fitting biblical history, persons, and events into general history, archaeology has demonstrated the validity of many biblical references and data. It has continued to cast light, whether implicitly or explicitly, on many of the Bible's customs, cultures, and settings during various periods of history. On the other hand, archaeology has also given rise to some real problems with regard to its findings. Thus, its work is an ongoing one that cannot be foreclosed too quickly or used merely as a confirming device.

Kaiser goes on to detail case after case in which the Bible, he says, "has aided in the identification of missing persons, missing peoples, missing customs and settings." He concludes:

This is not to say that archaeology is a cure-all for all the challenges brought to the text—it is not! There are some monstrous problems that remain—some created by the archaeological data itself. But since we have seen so many specific challenges over the years yield to such specific data in favor of the text, a presumption tends to build that we should go with the text until definite contrary information is available. This methodology that says that the text is innocent until proven guilty is not only recommended as a good procedure for American jurisprudence, but it is recommended in the area of examining the claims of the Scripture as well.

Collins comments upon a statement by Dever:

"there is little that we can salvage from Joshua's stories of the rapid, wholesale destruction of Canaanite cities and the annihilation of the local population. It simply did not happen; the archeological evidence is indisputable."

This is the judgment of one of the more conservative historians of ancient Israel. To be sure, there are far more conservative historians who try to defend the historicity of the entire biblical account beginning with Abraham, but their work rests on confessional presuppositions and is an exercise in apologetics rather than historiography. Most biblical scholars have come to terms with the fact that much (not all!) of the biblical narrative is only loosely related to history and cannot be verified.

— John J. Collins

As a young student, I heard a series of lectures given by a famous liberal Old Testament theologian on Old Testament introduction. And there one day learned that the fifth book of Moses (Deuteronomy) had not been written by Moses—although throughout it it claims to have been spoken and written by Moses himself. Rather, I heard Deuteronomy had been composed centuries later for quite specific purposes. Since I came from an orthodox Lutheran family, was deeply moved by what I heard—in particular, because it convinced me. so the same day I sought out my teacher during his hours and, in connection With the origin of Deuteronomy, let slip the remark, "So is the fifth book of Moses what might be called a forgery?" His answer was, "For God's sake, it may well be, but you can't say anything like that."

I wanted to use that quotation in order to show that the results of historical scholarship can be made known to the public—especially to believers—only with difficulty. Many Christians feel threatened if they hear that most of what was written in the Bible is (in historical terms) untrue and that none of the four New Testament Gospels was written by the author listed at the top of the text.

— Gerd Lüdemann