A flying saucer, or flying disc, is a purported type of disc-shaped unidentified flying object (UFO). The term was coined in 1947 by the United States (US) news media for the objects pilot Kenneth Arnold claimed flew alongside his airplane above Washington State. Newspapers reported Arnold's story with speed estimates implausible for aircraft of the period. The story preceded a wave of hundreds of sightings across the United States, including the Roswell incident and the Flight 105 UFO sighting. A National Guard pilot died in pursuit of a flying saucer in 1948, and civilian research groups and conspiracy theories developed around the topic. The concept quickly spread to other countries. Early reports speculated about secret military technology, but flying saucers became synonymous with aliens by 1950. The more general military terms unidentified flying object (UFO) and unidentified anomalous phenomena (UAP) have gradually replaced the term over time.

In science fiction, UFO sightings, UFO conspiracy theories, and broader popular culture, saucers are typically piloted by nonhuman beings. Most reported sightings describe saucers in the distance and do not mention a crew. Descriptions of the craft vary considerably. Early reports emphasized speed, but the descriptions shifted over the decades to the objects mostly hovering. They are generally said to be round, sometimes with a protrusion on top, but details of the shape vary between reports. Witnesses describe flying saucers as silent or deafening, with lights of every color, and flying alone or in formation. Size estimates range from small enough to fit in a living room to over 2,000 feet (610 m) in diameter. Sightings are most frequent at night. Astronomer Donald Howard Menzel concluded that the reports were too varied to all be describing the same type of objects. Experts have identified most reported saucers as known phenomena, including astronomical objects such as Venus, airborne objects such as balloons, and optical phenomena such as sun dogs.

1950s pop culture embraced flying saucers. The discs appeared in film, television, literature, music, toys, and advertising. Their reports influenced religious movements and were the subject of military investigations. The shape became visual shorthand for alien invaders. During the 1960s, saucers waned in popularity as UFOs were reported and depicted in other shapes. Discs ceased to be viewed as the standard shape for alien spacecraft but are still often depicted, sometimes for their retro value to evoke the early Cold War era.

History

Precursors

Reports of fantastical aircraft predate the first flying saucers. In antiquity, mysterious lights in the sky were interpreted as spiritual phenomena. In the 1800s, many newspapers reported massive airships with glowing lights and humming engines. These are often seen as precursors to flying saucer and UFO sightings. On January 25, 1878, the Denison Daily News printed an article in which John Martin, a local farmer, reported an object resembling a balloon flying "at wonderful speed". The newspaper said it appeared to be about the size of a saucer from his perspective, one of the first uses of the word "saucer" in association with a UFO. An outbreak of a number of sightings of mystery airships occurred in America in 1896 and 1897. During World War II, Allied pilots reported balls of light following their planes. They named the lights foo fighters and believed they were advanced Axis aircraft.

Many aspects of the typical flying saucer first appeared in science fiction. French sociologist Bertrand Méheust noted, for example, Jean de La Hire's 1908 novel La Roue fulgurante (The Lightning Wheel). In the novel, a flying disc-shaped machine abducts the protagonists via a beam of light.[11]: 206–8 Science fiction magazine Amazing Stories began publishing "The Shaver Mystery" in 1945. Written by Richard Sharpe Shaver and edited by Raymond A. Palmer, they were science fiction tales about technologically advanced "detrimental robots" that abducted humans, but the stories were presented as a true account of Shaver's life. Until the magazine ceased printing The Shaver Mystery, Amazing Stories' letter column was regularly full of readers sharing their own purportedly true sightings of the robots.

Before the flying saucer was coined as a term, fantasy artwork in pulp magazines depicted flying discs. Skeptical physicist Milton Rothman noted the appearance of so-called flying saucers in the fantasy artwork of 1930s pulp science fiction magazines, by artists such as Frank R. Paul. One of Paul's earliest depictions of a flying saucer appeared on the cover of the November 1929 issue of Hugo Gernsback's pulp science fiction magazine Science Wonder Stories. Science fiction illustrator Frank Wu wrote:

The point is that the idea of space vehicles shaped like flying saucers was imprinted in the national psyche for many years prior to 1947, when the Roswell incident took place. It didn't take much stretching for the first observers of UFOs to assume that the unknown objects hovering in the sky had the same disk shape as the science fictional vehicles.

Origins

The modern flying saucer concept, including the association with aliens, can be traced to the 1947 Kenneth Arnold UFO sighting.[16][6] On June 24, 1947, businessman and amateur pilot Kenneth Arnold landed at the Yakima, Washington airstrip. He told staff and friends that he'd seen nine unusual airborne objects. Arnold estimated their speed at 1,700 miles per hour, beyond the capabilities of known aircraft. Newspapers soon contacted Arnold for interviews. The East Oregonian reported his supposed aircraft as "saucer-like". In a June 26 radio interview, Arnold described them as "something like a pie plate that was cut in half with a sort of a convex triangle in the rear". Headline writers coined the terms "flying saucer" and "flying disk" (or "disc") for the story. Arnold later told CBS News that the early coverage "did not quote me properly [...] when I described how they flew, I said that they flew like they take a saucer and throw it across the water. Most of the newspapers misunderstood and misquoted that, too. They said that I said that they were saucer-like; I said that they flew in a saucer-like fashion." The circular shape of typical flying saucers may be due to reporters mistaking Arnold's "saucer-like" description of motion.

Arnold's story preceded a wave of hundreds of flying saucer reports. Lieutenant Governor of Idaho Donald S. Whitehead claimed he saw a fast-moving object resembling a meteor around the time of Arnold's sighting. In early July, head of Air Materiel Command Nathan F. Twining told reporters that "anyone seeing the objects" should contact Wright Field. The next widely publicized report was the sighting by a United Airlines crew on July 4 of nine more disc-like objects pacing their plane over Idaho.

The public was divided on the potential origin of the saucers. Arnold told military intelligence officers he suspected the discs were experimental aircraft, and early newspapers reported Arnold saying, "I don't know what they were—unless they were guided missiles." News media speculated on a Soviet origin, and many war veterans connected them to the foo fighters seen during World War II. A Gallup Poll found that 90% of Americans were aware of the saucer stories, and 16 percent believed they were secret military weapons, most likely American. The most common explanation given was some type of illusion or mirage. Less than one percent believed they were alien craft. One report from Seattle, Washington, described a hammer and sickle painted onto a flying disc. The stories spread to other countries, where they were influenced by local political and social concerns. In Europe, which was still recovering from the Second World War, saucers were often reported with rocket-like features. German newspapers reported flying saucers that exploded or had tails of fire. The names for the discs were largely derived from the English "flying saucer" including the French soucoupe volante, Spanish platillo volante, Portuguese disco voador, Swedish flygande tefat, German fliegende Untertasse, and Italian disco volante.

The 1947 sightings peaked in the days after the Fourth of July and declined rapidly through mid-July. Multiple organizations offered $1,000 rewards for hard proof. In the widely reported July 7, 1947, Twin Falls saucer hoax, four teenagers in Idaho fabricated a crashed disc from jukebox parts. On July 8, the Army Air Force base at Roswell, New Mexico, issued a press release saying that they had recovered a "flying disc" from a nearby ranch; the so-called Roswell UFO incident made front-page news. International media covered the military's announcement of a crashed disc, but within 24 hours were reporting the military's retraction and explanation that the material was balloon debris. By July 11, the most widely reported story was a North Hollywood resident's claim that a 30-inch galvanized iron disc containing glass radio tubes had crashed in his garden. Newspapers quoted Fire Battalion Chief Wallace Newcombe's assessment, "It doesn't look to me like it could fly."

The Air Force collected over a hundred reports at Wright Field, now Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio. Air Force General Nathan Twining established Project SAUCER, later renamed Project Sign, the first in a series of UFO investigations by the US Government. Other national governments followed suit. Canada began Project Magnet and the United Kingdom launched the Flying Saucer Working Party in 1950, which attributed saucer reports to meteorological phenomena, astronomical phenomena, misidentification, optical illusions, misconceptions, or hoaxes.

Development

By the 1950s, the term "flying saucer" was widely associated with extraterrestrial life. After commercial pilots Clarence Chiles and John Whitted reported a glowing cylindrical object flying past their plane in 1948, the US Air Force began to seriously investigate the possibility of an alien origin, but also concluded that reported discs "seem inconsistent with the requirements for space travel." In a 1950 interview on flying saucers, Kenneth Arnold said, "if it's not made by our science or our Army Air Forces, I am inclined to believe it's of an extra-terrestrial origin". This extraterrestrial hypothesis was accompanied by other unusual theories. Meade Layne speculated that they came from an alternate dimension. Many people claimed to be the inventors of the discs but could offer no evidence. From 1947 to 1970, there was a broad range of overlapping and contradictory explanations for the saucers' origin and purpose, even among proponents.

Beliefs about flying saucers were influenced by pulp science fiction. Amazing Stories editor Ray Palmer transitioned from publishing the purportedly true Shaver Mystery, to publishing and organizing UFO investigations. In 1946, Palmer published Fred Crisman's letters about his encounters with underground beings. The following year, Crisman sent Palmer pale metallic fragments along with a report from his employee, Harold Dahl, about a malfunctioning flying saucer. Palmer recruited Kenneth Arnold to investigate Crisman and Dahl's Maury Island incident. The fragments turned out to be slag from a local smelter, but the men in black that Crisman and Dahl claimed were following them would become a common element in later UFO literature. Gray Barker popularized the idea of "men in black" who intimidate or silence UFO witnesses in his book They Knew Too Much About Flying Saucers. Palmer launched the magazine Fate in 1948, claiming to offer "the truth about flying saucers". It was the first of many non-fiction paranormal magazines, a genre that flourished in the 1950s.

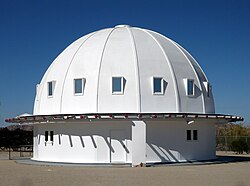

A flying saucer movement developed during the 1950s. It was influenced by scientific research, occult practices, pop culture, existing religions, and earlier myths. In reports and in popular media such as the 1951 film The Day the Earth Stood Still, saucers and their pilots were characterized as messengers. The first wave of so-called contactees, George Van Tassel, George Adamski, Truman Bethurum, Orfeo Angelucci, and George Hunt Williamson, all claimed to have ridden aboard the saucers and brought back messages for humanity. New religions and institutions arose around the contactees. Van Tassel built the Integratron, a domed structure near Landers, California, intended to facilitate further contact with aliens, physical rejuvenation, and a kind of spiritual time travel. According to George King, he founded the Aetherius Society—a new religious movement influenced by theosophy—at the direct instruction of an extraterrestrial. Some existing religions began to incorporate flying saucers. The Nation of Islam taught that the end of the world would be brought about by the "Mother Wheel" or "Mother Plane", a flying saucer half a mile wide. During the same time that Margaret Murray's "Old Religion" or witch-cult hypothesis was being discredited in academic circles, its core idea—a lost civilization remembered in myth—was being embraced in pulp fiction, occult groups, and the growing UFO movement. Several authors speculated that ancient astronauts piloting UFOs were the cause of myths and religions. Schoolteacher Robert Dione wrote God Drives a Flying Saucer to reframe biblical miracles and the Miracle of the Sun as the work of humanoid aliens piloting flying saucers. Later, Erich von Däniken released Chariots of the Gods?, a work of pseudoscience that attributed ancient artifacts and monuments to its purported ancient astronauts.

Ufology developed as a parallel social movement. Well-known Variety columnist Frank Scully published Behind the Flying Saucers in 1950. The book presents the Aztec, New Mexico, crashed saucer hoax as the true account of an alien craft that "gently pancaked to earth like Sonja Henie imitating a dying swan" and was recovered by the United States government. The hoaxers were convicted of fraud for selling useless dowsing equipment to the oil industry based on a claimed alien origin, but the book described one of the men as a doctor with "more degrees than a thermometer". Donald Keyhoe took a "nuts and bolts" approach to the idea of the government covering up alien life in his 1950 book The Flying Saucers Are Real. When the popular and respected Life magazine ran "Have We Visitors From Space?" in 1952, taking seriously ideas of alien visitors, a wave of sightings followed. The 1952 sightings spurred Leonard H. Stringfield to form an early UFO investigation group called the Civilian Investigating Group for Aerial Phenomena and to publish research on UFOs. Albert K. Bender started his own International Flying Saucer Bureau in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in 1952. Influenced by these works, James W. Moseley began to tour the country interviewing witnesses and distributing a newsletter for the growing saucer subculture.

Within a decade of the first saucer sightings, reports spread to other countries, leading to the emergence of local groups and ufologists. Antonio Ribera started Centro de Estudios Interplanetarios in Spain, and Edgar Jarrold founded the Australia Flying Saucer Bureau. In France, UFO groups overlapped with occult groups and the anti-nuclear movement. Reports have been more often made in the countries where UFO groups are in operation, such as the United States, France, Spain, the United Kingdom, Brazil, Chile, and Argentina. By the end of the decade, The Case for the UFO author Morris K. Jessup reflected on his field: "This embryonic science is as full of cults, feuds, and dogmas as a dog is of fleas. There are probably more opinions about the nature and purpose of UFO's as there are Ufologers."

UFO photography emerged as a subgenre of documentary photography, showing often blurry or abstract discs framed by otherwise everyday settings. Notable examples include the 1950 McMinnville photographs, the Passaic UFO photographs, and the photographs of contactee George Adamski. Some of the alleged flying saucer photographs of the era were hoaxes, created using everyday objects such as hubcaps. German rocket scientist Walther Johannes Riedel analyzed George Adamski's UFO photos and found them to be faked. The UFO's "landing struts" were General Electric light bulbs with GE logos visible on them. UFO researcher Joel Carpenter identified the body of Adamski's "flying saucer" as the lampshade from a 1930s pressure lantern.

Flying saucers are now considered retro and emblematic of the 1950s and of science fiction B movies. The term "flying saucer" was gradually supplanted by "UFO" and later "UAP". Discs ceased to be the standard shape in UFO reports, and a broader variety of objects were reported. Recent reports more often describe spherical and triangular UFOs.

Description

Identification

Experts have identified the majority of flying saucer and broader UFO reports with known phenomena. British government investigations in the 1950s found that the vast majority of reports were misidentifications or hoaxes. Common explanations for saucer sightings include the planet Venus, weather phenomena such as ice crystals, balloons, and airborne trash. The US Navy and General Mills launched thousands of top-secret Skyhook spy balloons by the mid-1950s. Because they floated at high altitude, it was difficult to judge the speed of the massive balloons, and they were widely reported as flying saucers. Kentucky Air National Guard pilot Thomas Mantell died while pursuing an unknown round object "of tremendous size", later identified as a Skyhook balloon. News media reported Mantell as having crashed "chasing [a] flying saucer", and some lost Skyhook balloons were tracked down using news reports of UFO sightings.

In the mid-1950s, psychologists began to study why people believed in flying saucers despite the lack of evidence. French psychiatrist Georges Heuyer viewed the phenomenon as a kind of global folie à deux, or shared delusion, triggered by fear of a possible nuclear holocaust. In the 1970s, French UFO researcher Michel Monnerie compared reports that were later identified with those that remained unexplained. Monnerie found no difference in the frequency of paranormal phenomena reported alongside the sightings identified later as mundane known objects. These findings led him to develop the thesis that the saucer-specific experiences were a "psychosocial" process of myth-making triggered by but not caused by aerial phenomena. This psychosocial UFO hypothesis became a popular explanation in France.

Reported sightings

Eyewitness descriptions differ in reported appearance, movement, and purpose. In a 1963 overview of flying saucers, astronomer Donald Howard Menzel found some broad traits across sightings but noted that "no two reports describe exactly the same kind of UFO." Menzel found saucers were usually reported as round but included objects shaped like dining saucers, teardrops, cigars, kidney beans, the planet Saturn, and yarn spindles. Saucers often were reported with a dome or knob-shaped protrusion on the top side. Size estimates ranged from 20 feet to over 2,000 feet (610 m) in diameter. Menzel found saucers reported in nearly every color, often glowing or flashing. The sightings had little consistency in reported movement. Witnesses described hearing sounds ranging from a thunderclap to total silence. Sightings typically took place at night, around sunset or sunrise. Almost all witnesses described distant saucers in flight. Menzel concluded, "No single phenomenon could possibly display such infinite variety."

If a witness describes a saucer's crew, they usually regard them as extraterrestrial. Grey aliens gradually became the most reported type of pilot, but a vast range of beings have been reported. The diversity was greater in the 1950s and early 1960s, when witnesses reported the aliens variously as hairy, hairless, monstrous, gorgeous, gigantic, dwarfish, robotic, insectoid, avian, Nordic, or grey-skinned. Historian Greg Eghigian argues that this gradual standardization indicates a cultural process to create a broadly recognizable design.

Witnesses consistently describe and depict flying saucers as ahead of contemporary technology. When comparing the 1947 saucer reports to the mystery airships of the 1800s, sociologist Robert Bartholomew found that the claimed observations "reflected popular social and cultural expectations of each period". The mystery airship sightings of the 1800s included details such as metal hulls, propellers, searchlights, and large wings. The 1947 sightings—occurring months before Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier—emphasized the "incredible speed" of flying saucers. While most 1947 reports focused on speed, this fell to 41 percent in 1971 and 22 percent in 1986. In the 1950s, hovering flying saucers were associated with contactees and hoaxes. By 1986, almost half of reported UFOs were said to hover slowly or remain motionless.

Fictional portrayals

In popular media, flying saucers underwent a change in motion similar to the shift in eyewitness reports. Early portrayals emphasized high speed maneuvers, but later media gradually shifted to slowly hovering discs. Early films such as The Flying Saucer (1950) and film serials such as Bruce Gentry – Daredevil of the Skies (1949), show saucers streaking past at high speeds. The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) mentions high speeds tracked by radar but also includes a slow landing scene. The 1960s television series The Invaders prominently features a slow landing scene in every episode. Many later iconic flying saucer films, including Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and Fire in the Sky (1993), depict hovering and slow movements.

Popular culture

Since the late 1940s, flying discs have increasingly become associated with a cultural conception of aliens that reflects the social and political anxieties of the 20th century. Fictional flying saucers represent concerns about atomic warfare, the Cold War, loss of bodily integrity, xenophobia, government secrecy, and the question of whether humanity is alone in the universe. Reports from witnesses influenced popular media, which led to greater interest in flying saucers. For the film Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, producer Charles H. Schneer adapted Donald Keyhoe's UFO books for the screenplay, while special effects artist Ray Harryhausen consulted with contactee George Adamski about the saucer design. No correlation has been found between the release of major UFO films and spikes in sightings. A disc, often domed or emitting a beam of light, has become visual shorthand for aliens. In 2017, the flying saucer emoji was added to Unicode.

Although the symbol now signifies alien life, similar motifs had unrelated religious and astronomical meanings in the past. Some ufologists have attempted to re-interpret premodern art to support pseudohistorical claims of ancient alien interactions with humanity. Ufologists claim that early portrayals of flying discs can establish a historical basis for their existence as physical craft or some other type of external phenomena. However, experts have consistently explained purported portrayals of ancient UFOs as artifacts of the cultures producing them. For example, Italian Renaissance painter Carlo Crivelli put a disc-shaped element in his 1486 altarpiece The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius that art historian Massimo Polidoro described as "a vortex of angels in the clouds". The artists and audiences of the time understood it as an artistic device representing the influence of the Christian God, not extraterrestrials. The device is seen more clearly in many contemporary works, notably Luca Signorelli's 1491 Annunciation.

Literature

Several precursors to modern flying saucers appeared in science fiction literature, including The Shaver Mystery. Richard Sharpe Shaver's stories about a secret technologically advanced civilization of "detrimental robots" inside the earth were published as a true account of his life. Backlash from the science fiction community carried over to UFO literature. Saucers did appear in conventional science fiction, but a genre emerged that treated fantastical stories as either true or plausibly true. The debut issue of Mystic magazine asked readers, "When you read this story, you will tell yourself that it is fiction; the editors assure you that it is. But what if—it isn't?" The Fortec Conspiracy, a science fiction novel, both drew from and fed into crashed saucer rumors. Major newspapers rarely did reviews for saucer books but printed their sensationalist advertisements claiming to prove that flying saucers had landed or were being covered up. Cultural studies scholar Jonathan Gray describes this type of widely-viewed alarmist ad as a paratext (related to the central text but not a part of it), which can reach a much broader audience than the text itself.

Advertisements leveraged cultural interest in flying saucers from the earliest reports. Magazines were promoted as offering skeptical, debunking explanations for the phenomenon. From 1947 into the 1970s, marketing leveraged the discs' potential as advanced technology. By the 1980s, saucers in advertisement were used to evoke awe towards their potential pilots more than futurism.

Aliens and flying discs were common in 1950s science fiction comics that flourished after the Golden Age of Comic Books. Launched in the 1960s, the comic book anthology UFO Flying Saucers featured illustrations of supposedly real sightings. The opening to its first issue declared, "Our scientists have seen them! Our airmen have fought them!" As the 1950s progressed, former pulp readers turned their attention to the growing medium of television.

Film and television

Many early portrayals of flying saucers linked them to the Cold War. The 1949 film serial Bruce Gentry – Daredevil of the Skies featured a man-made flying saucer, and the 1950 film The Flying Saucer focused on Cold War espionage. Saucer films in the 1950s featured alien pilots, but many continued to center on Cold War fears. The Thing from Another World (1951) was a loose adaptation of John W. Campbell's "Who Goes There?", updated to include aliens and relocated to Alaska, where Americans feared a Russian attack. Later that year, The Day the Earth Stood Still had its human-looking alien Klaatu give audiences explicit warnings about a possible nuclear holocaust. The Day the Earth Stood Still and The Thing from Another World were financial successes that established the market for an "alien visitor" subgenre of science fiction that merged flying saucers into existing space opera tropes. Slowly hovering discs, such as the one from the landing scene in The Day the Earth Stood Still, appeared throughout science fiction, including It Came from Outer Space (1953), Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956), and the television series The Invaders. While contactees described aliens as benevolent messengers, Hollywood films often depicted them as monstrous antagonists.

Other countries adapted the largely American phenomenon at different times, adding elements of the local culture. Early British films were low-budget productions such as Devil Girl from Mars (1954) and Stranger from Venus (1954). Japanese filmmakers incorporated flying discs and alien invaders into the tokusatsu tradition in mid-50s films such as Fearful Attack of the Flying Saucers and Warning from Space. Indian cinema began to incorporate alien invaders in the 1960s, starting with the Tamil-language Kalai Arasi. An adaptation of Bankubabur Bandhu by Satyajit Ray was never completed but may have influenced other works of science fiction. In Spain, alien-themed television shows became popular in the 1960s.

Flying saucers quickly spread to other genres. In Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's big-budget Forbidden Planet, a futuristic 1956 adaptation of William Shakespeare's play The Tempest, humans travel through space in the United Planets Cruiser C-57D, a ship resembling a flying saucer. The Twilight Zone episodes "The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street", "Third from the Sun", "Death Ship", "To Serve Man", "The Invaders", and "On Thursday We Leave for Home", all make use of the iconic saucer from Forbidden Planet. The C-57D was followed by other disc-shaped spacecraft in broader science fiction, such as the Jupiter 2 from the television series Lost in Space (1965–1968). Saucers appeared in the television series Babylon 5 (1994–1998) as starships used by a race called the Vree. Aliens in the film Independence Day (1996) attacked humanity in giant city-sized saucer-shaped spaceships.

Flying saucers were supplanted by other concepts and fell out of favor with Hollywood filmmakers. After 1956, American saucer films were mainly B movies. Plan 9 from Outer Space is infamous for its "pie-pan" saucers dangled from visible piano wire. Television shows and British films continued to depict flying discs and alien invaders into the 1960s. Various saucer designs have appeared in Doctor Who, such as those used by the Daleks in Daleks' Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. or the Cybermen in "The Tenth Planet". Italy produced a wave of low-budget films, often space operas or comedies, including Omicron (1963) and Il disco volante (1964). By the end of the 1960s, Japan, Italy, and Britain largely ceased producing saucer films. Disc-shaped spacecraft fell out of favor in straight science fiction but continued to be used ironically in comedies. The image is often invoked retrofuturistically to produce a nostalgic feel in period works. For example, Mars Attacks! (1996) draws on the flying saucer as part of the larger satire of 1950s B movie tropes.

Architecture

The sleek, silver flying saucer is widely regarded as a symbol of 1950s culture. The motif is common in Googie architecture and Atomic Age décor. Notable flying saucer structures include Seattle's Space Needle and Los Angeles International Airport's Theme Building. Googie architecture in California, such as the Chemosphere home, influenced the futuristic structures in the 1960s cartoon The Jetsons. The cartoon popularized the style to such an extent, that it is often referred to as the "Jetsons look". Architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who collaborated on the design of the flying saucer in The Day The Earth Stood Still, went on to use the flying saucer as an architectural motif. Wright's circular Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, United States, is capped by a flattened dome over a hundred feet across.

Spaceships are one of the subjects of novelty architecture. Also known as mimetic architecture, novelty architecture is the practice of creating structures shaped like other existing objects. The Communist-era Kielce Bus Station in Kielce, Poland, was designed by architect Edward Modrzejewski to resemble a UFO. The historic landmark arena in Katowice, Poland, is called Spodek (Polish for "saucer") based on its resemblance to the saucers of 1960s science fiction. Other modernist and brutalist UFO structures include the Ukrainian Institute of Scientific, Technical and Economic Information, Bulgaria's concrete Buzludzha monument, the Most SNP in Bratislava, Slovakia, and The Flying Saucer in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. The Westall UFO was commemorated with the Grange Reserve UFO Park, featuring a UFO with red slides modeled after the reported sighting. Roswell, New Mexico, is a UFO tourist destination in the Southwestern United States. Many structures in Roswell, including the streetlights and the McDonald's, are designed around alien themes. Moonbeam, Ontario, Canada, has an alien for its mascot and a prominent roadside flying saucer at its welcome center. UFO-shaped homes include the Futuro pods designed by Matti Suuronen, the former Sanzhi UFO houses from the Sanzhi District, New Taipei, Taiwan, and artist Harry Visser's iconic home in Roodepoort, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Broader pop culture

Flying saucers were a ubiquitous part of pop culture from 1947 into the mid-1970s. Flying disc motifs were used in toys and other novelties soon after the earliest reports. The frisbee was released in 1948 and initially branded the "flying saucer". Flying saucer candy was introduced in the 1950s when a Belgian producer of communion wafers had a dip in sales. Along with other vintage candies, they have since seen renewed interest from customers as "retro". In the 1950s and early 1960s, Japan was a major manufacturer of tin toys often with space themes such as robots, rockets, and flying discs. Throughout the 1950s, musicians such as Billy Lee Riley, Jesse Lee Turner, and Betty Johnson released novelty songs about flying discs and alien invaders. Bill Buchanan and Dickie Goodman released the first break-in record, "The Flying Saucer", which took the form of a mock news broadcast covering an alien invasion. Disneyland opened Flying Saucers, an attraction where guests could pilot a hovering disc by tilting their own body.

Video games have a long history of depicting flying saucers, typically as antagonists. In the arcades, the popular early shooting games Asteroids (1979) and Space Invaders (1978) featured flying saucers as "bonus" enemies that only emerged briefly. Super Mario Land, one of Nintendo's launch titles for the original Game Boy, contained spaceships modeled after photographs by George Adamski and set among various monuments falsely attributed to ancient astronauts, such as the Egyptian pyramids and the monolithic Moai of Easter Island. The XCOM series tasks players with countering an invasion of aliens landing on Earth in flying discs. Saucers have appeared as a craft that players can control in Fortnite, Destroy All Humans, and Spore.

![{\displaystyle \gamma :[a,b]\to M}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b5c2d8d0dd04be91ac24d40469cc8b8ad0c7057d)