Mark Twain

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Mark Twain | |

|---|---|

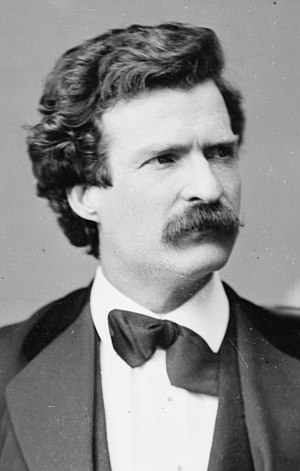

Mark Twain, detail of photo by Mathew Brady, February 7, 1871

| |

| Born | Samuel Langhorne Clemens November 30, 1835 Florida, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | April 21, 1910 (aged 74) Redding, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Pen name | Mark Twain |

| Occupation | Writer, lecturer |

| Nationality | American |

| Notable works | Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer |

| Spouse | Olivia Langdon Clemens (m. 1870–1904) |

| Children | Langdon, Susy, Clara, Jean |

| Signature |  |

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910),[1] better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist. He wrote The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and its sequel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885),[2] the latter often called "the Great American Novel."

Twain grew up in Hannibal, Missouri, which provided the setting for Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer. After an apprenticeship with a printer, he worked as a typesetter and contributed articles to the newspaper of his older brother Orion Clemens. He later became a riverboat pilot on the Mississippi River before heading west to join Orion in Nevada. He referred humorously to his singular lack of success at mining, turning to journalism for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise.[3] In 1865, his humorous story, "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County," was published, based on a story he heard at Angels Hotel in Angels Camp, California, where he had spent some time as a miner. The short story brought international attention, and was even translated into classic Greek.[4] His wit and satire, in prose and in speech, earned praise from critics and peers, and he was a friend to presidents, artists, industrialists, and European royalty.

Though Twain earned a great deal of money from his writings and lectures, he invested in ventures that lost a great deal of money, notably the Paige Compositor, which failed because of its complexity and imprecision. In the wake of these financial setbacks, he filed for protection from his creditors via bankruptcy, and with the help of Henry Huttleston Rogers eventually overcame his financial troubles. Twain chose to pay all his pre-bankruptcy creditors in full, though he had no legal responsibility to do so.

Twain was born shortly after a visit by Halley's Comet, and he predicted that he would "go out with it," too. He died the day following the comet's subsequent return. He was lauded as the "greatest American humorist of his age,"[5] and William Faulkner called Twain "the father of American literature."[6]

Early life

Samuel Langhorne Clemens was born in Florida, Missouri, on November 30, 1835. He was the son of Jane (née Lampton; 1803–1890), a native of Kentucky, and John Marshall Clemens (1798–1847), a Virginian by birth. His parents met when his father moved to Missouri and were married several years later, in 1823.[7][8] He was the sixth of seven children, but only three of his siblings survived childhood: his brother Orion (1825–1897); Henry, who died in a riverboat explosion (1838–1858); and Pamela (1827–1904). His sister Margaret (1833–1839) died when he was three, and his brother Benjamin (1832–1842) died three years later. Another brother, Pleasant (1828–1829), died at six months.[9] Twain was born two weeks after the closest approach to Earth of Halley's Comet.When he was four, Twain's family moved to Hannibal, Missouri,[10] a port town on the Mississippi River that inspired the fictional town of St. Petersburg in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.[11] Missouri was a slave state and young Twain became familiar with the institution of slavery, a theme he would later explore in his writing. Twain's father was an attorney and judge.[12] The Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad was organized in his office in 1846. The railroad connected the second and third largest cities in the state and was the westernmost United States railroad until the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. It delivered mail to and from the Pony Express.[13]

In 1847, when Twain was 11, his father died of pneumonia.[14] The next year, he became a printer's apprentice. In 1851, he began working as a typesetter and contributor of articles and humorous sketches for the Hannibal Journal, a newspaper owned by his brother Orion. When he was 18, he left Hannibal and worked as a printer in New York City, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Cincinnati. He joined the newly formed International Typographical Union, the printers union, and educated himself in public libraries in the evenings, finding wider information than at a conventional school.[15]

Clemens came from St. Louis on the packet Keokuk in 1854[16] and lived in Muscatine during part of the summer of 1855. The Muscatine newspaper published eight stories, which amounted to almost 6,000 words.[17]

Twain describes in Life on the Mississippi how when he was a boy "there was but one permanent ambition" among his comrades: to be a steamboatman. "Pilot was the grandest position of all. The pilot, even in those days of trivial wages, had a princely salary - from a hundred and fifty to two hundred and fifty dollars a month, and no board to pay." As Twain describes it, the pilot's prestige exceeded that of the captain. The pilot had to "get up a warm personal acquaintanceship with every old snag and one-limbed cottonwood and every obscure wood pile that ornaments the banks of this river for twelve hundred miles; and more than that, must ... actually know where these things are in the dark..." Steamboat pilot Horace E. Bixby took on Twain as a "cub" pilot to teach him the river between New Orleans and St. Louis for $500, payable out of Twain's first wages after graduating. Twain studied the Mississippi, learning its landmarks, how to navigate its currents effectively, and how to "read the river" and its constantly shifting channels, reefs, submerged snags and rocks that would "tear the life out of the strongest vessel that ever floated."[18] It was more than two years before he received his steamboat pilot license in 1859. This occupation gave him his pen name, Mark Twain, from "mark twain," the leadsman's cry for a measured river depth of two fathoms, which was safe water for a steamboat. While training, Samuel convinced his younger brother Henry to work with him. Henry was killed on June 21, 1858, when the steamboat he was working on, the Pennsylvania, exploded. Twain had foreseen this death in a dream a month earlier,[19]:275 which inspired his interest in parapsychology; he was an early member of the Society for Psychical Research.[20] Twain was guilt-stricken and held himself responsible for the rest of his life. He continued to work on the river and was a river pilot until the American Civil War broke out in 1861 and traffic along the Mississippi was curtailed.

At the start of the Civil War, Twain enlisted briefly in a Confederate local unit. He then left for Nevada to work for his brother, Orion Clemens, who was secretary of the Nevada Territory, which Twain describes in his book Roughing It.[21][22] Twain later wrote a sketch, "The Private History of a Campaign That Failed," which told how he and his friends had been Confederate volunteers for two weeks before disbanding their company.[23]

Travels

Library of Twain House, with hand-stenciled paneling, fireplaces from India, embossed wallpapers, and hand-carved mantel purchased in Scotland

Twain joined Orion, who in 1861 became secretary to James W. Nye, the governor of Nevada Territory, and headed west. Twain and his brother traveled more than two weeks on a stagecoach across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains, visiting the Mormon community in Salt Lake City.

Twain's journey ended in the silver-mining town of Virginia City, Nevada, where he became a miner on the Comstock Lode.[23] Twain failed as a miner and worked at a Virginia City newspaper, the Territorial Enterprise.[24] Working under writer and friend Dan DeQuille, here he first used his pen name. On February 3, 1863, he signed a humorous travel account "Letter From Carson – re: Joe Goodman; party at Gov. Johnson's; music" with "Mark Twain."[25]

His experiences in the American West inspired Roughing It and his experiences in Angels Camp, California, in Calaveras County, provided material for "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County".

Twain moved to San Francisco, California, in 1864, still as a journalist. He met writers such as Bret Harte and Artemus Ward. The young poet Ina Coolbrith may have romanced him.[26]

His first success as a writer came when his humorous tall tale, "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County," was published in a New York weekly, The Saturday Press, on November 18, 1865. It brought him national attention. A year later, he traveled to the Sandwich Islands (present-day Hawaii) as a reporter for the Sacramento Union. His travelogues were popular and became the basis for his first lectures.[27]

In 1867, a local newspaper funded a trip to the Mediterranean. During his tour of Europe and the Middle East, he wrote a popular collection of travel letters, which were later compiled as The Innocents Abroad in 1869. It was on this trip that he met his future brother-in-law, Charles Langdon. Both were passengers aboard the Quaker City on their way to the Holy Land. Langdon showed a picture of his sister Olivia to Twain; Twain claimed to have fallen in love at first sight.

Upon returning to the United States, Twain was offered honorary membership in the secret society Scroll and Key of Yale University in 1868.[28] Its devotion to "fellowship, moral and literary self-improvement, and charity" suited him well.

Marriage and children

Throughout 1868, Twain and Olivia Langdon corresponded, but she rejected his first marriage proposal. Two months later, they were engaged. In February 1870, Twain and Langdon were married in Elmira, New York,[27] where he had courted her and had overcome her father's initial reluctance.[29]

She came from a "wealthy but liberal family," and through her, he met abolitionists, "socialists, principled atheists and activists for women's rights and social equality," including Harriet Beecher Stowe (his next-door neighbor in Hartford, Connecticut), Frederick Douglass, and the writer and utopian socialist William Dean Howells,[30] who became a long-time friend. The couple lived in Buffalo, New York, from 1869 to 1871. Twain owned a stake in the Buffalo Express newspaper and worked as an editor and writer. While they were living in Buffalo, their son Langdon died of diphtheria at age 19 months. They had three daughters: Susy (1872–1896), Clara (1874–1962)[31] and Jean (1880–1909). The couple's marriage lasted 34 years, until Olivia's death in 1904. All of the Clemens family are buried in Elmira's Woodlawn Cemetery.

Twain moved his family to Hartford, Connecticut, where starting in 1873 he arranged the building of a home (local admirers saved it from demolition in 1927 and eventually turned it into a museum focused on him). In the 1870s and 1880s, Twain and his family summered at Quarry Farm, the home of Olivia's sister, Susan Crane.[32][33] In 1874,[32] Susan had a study built apart from the main house so that her brother-in-law would have a quiet place in which to write. Also, Twain smoked pipes constantly, and Susan Crane did not wish him to do so in her house. During his seventeen years in Hartford (1874–1891) and over twenty summers at Quarry Farm, Twain wrote many of his classic novels, among them The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876), The Prince and the Pauper (1881), Life on the Mississippi (1883), Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885) and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889).

Twain made a second tour of Europe, described in the 1880 book A Tramp Abroad. His tour included a stay in Heidelberg from May 6 until July 23, 1878, and a visit to London.

Love of science and technology

Twain in the lab of Nikola Tesla, early 1894

Twain was fascinated with science and scientific inquiry. He developed a close and lasting friendship with Nikola Tesla, and the two spent much time together in Tesla's laboratory.

Twain patented three inventions, including an "Improvement in Adjustable and Detachable Straps for Garments" (to replace suspenders) and a history trivia game.[34] Most commercially successful was a self-pasting scrapbook; a dried adhesive on the pages needed only to be moistened before use.

His book A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court features a time traveler from the contemporary US, using his knowledge of science to introduce modern technology to Arthurian England. This type of storyline would later become a common feature of a science fiction sub-genre, alternate history.

In 1909, Thomas Edison visited Twain at his home in Redding, Connecticut, and filmed him. Part of the footage was used in The Prince and the Pauper (1909), a two-reel short film. It is said to have been the only known existing film footage of Twain.[35]

Financial troubles

Twain made a substantial amount of money through his writing, but he lost a great deal through investments, mostly in new inventions and technology, particularly the Paige typesetting machine. It was a beautifully engineered mechanical marvel that amazed viewers when it worked, but it was prone to breakdowns. Twain spent $300,000 (equal to $8,200,000 in inflation-adjusted terms [36]) on it between 1880 and 1894;[37] but, before it could be perfected, it was made obsolete by the Linotype. He lost not only the bulk of his book profits but also a substantial portion of his wife's inheritance.[38]

Twain also lost money through his publishing house, Charles L. Webster and Company, which enjoyed initial success selling the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant but went broke soon after, losing money on a biography of Pope Leo XIII; fewer than two hundred copies were sold.[38]

Twain's writings and lectures, combined with the help of a new friend, enabled him to recover financially.[39] In 1893, he began a 15-year-long friendship with financier Henry Huttleston Rogers, a principal of Standard Oil. Rogers first made Twain file for bankruptcy. Then Rogers had Twain transfer the copyrights on his written works to his wife, Olivia, to prevent creditors from gaining possession of them. Finally, Rogers took absolute charge of Twain's money until all the creditors were paid.

Twain accepted an offer from Robert Sparrow Smythe[40] and embarked on a year-long, around-the-world lecture tour in July 1895[41] to pay off his creditors in full, although he was no longer under any legal obligation to do so.[42] It would be a long, arduous journey and he was sick much of the time, mostly from a cold and a carbuncle. The itinerary took him to Hawaii, Fiji, Australia, New Zealand, Sri Lanka, India, Mauritius, South Africa and England. Twain's three months in India became the centerpiece of his 712-page book Following the Equator. He joined the Anti-Imperialist League in 1898, in opposition to the U.S. annexation of the Philippines.[citation needed]

In mid-1900, he was the guest of newspaper proprietor Hugh Gilzean-Reid at Dollis Hill House, located on the north side of London, UK. In regard to Dollis Hill, Twain wrote that he had "never seen any place that was so satisfactorily situated, with its noble trees and stretch of country, and everything that went to make life delightful, and all within a biscuit's throw of the metropolis of the world."[43] He then returned to America in 1900, having earned enough to pay off his debts.

Speaking engagements

Twain was in demand as a featured speaker, performing solo humorous talks similar to what would become stand-up comedy.[44] He gave paid talks to many men's clubs, including the Authors' Club, Beefsteak Club, Vagabonds, White Friars, and Monday Evening Club of Hartford. In the late 1890s, he spoke to the Savage Club in London and was elected honorary member. When told that only three men had been so honored, including the Prince of Wales, he replied "Well, it must make the Prince feel mighty fine."[45] In 1897, Twain spoke to the Concordia Press Club in Vienna as a special guest, following diplomat Charlemagne Tower, Jr.. In German, to the great amusement of the assemblage, Twain delivered the speech "Die Schrecken der deutschen Sprache" ("The Horrors of the German Language").[46] In 1901, Twain was invited to speak at Princeton University's Cliosophic Literary Society, where he was made an honorary member.[47]Later life and death

| “ | ...the report is greatly exaggerated | ” |

—Mark Twain when it was reported he had died[48]

| ||

Mark Twain in 1895 by Napoleon Sarony

Twain passed through a period of deep depression that began in 1896 when his daughter Susy died of meningitis. Olivia's death in 1904 and Jean's on December 24, 1909, deepened his gloom.[49] On May 20, 1909, his close friend Henry Rogers died suddenly. In 1906, Twain began his autobiography in the North American Review. In April, Twain heard that his friend Ina Coolbrith had lost nearly all she owned in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, and he volunteered a few autographed portrait photographs to be sold for her benefit. To further aid Coolbrith, George Wharton James visited Twain in New York and arranged for a new portrait session. Initially resistant, Twain admitted that four of the resulting images were the finest ones ever taken of him.[50]

Twain formed a club in 1906 for girls he viewed as surrogate granddaughters, the Angel Fish and Aquarium Club. The dozen or so members ranged in age from 10 to 16. Twain exchanged letters with his "Angel Fish" girls and invited them to concerts and the theatre and to play games. Twain wrote in 1908 that the club was his "life's chief delight".[51] In 1907 Twain met Dorothy Quick (then aged 11) on a transatlantic crossing, beginning "a friendship that was to last until the very day of his death".[52]

Oxford University awarded Twain an honorary doctorate in letters (D.Litt.) in 1907.

Mark Twain headstone in Woodlawn Cemetery.

In 1909, Twain is quoted as saying:[53]

"I came in with Halley's Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don't go out with Halley's Comet. The Almighty has said, no doubt: 'Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.' "His prediction was accurate—Twain died of a heart attack on April 21, 1910, in Redding, Connecticut, one day after the comet's closest approach to Earth.

Upon hearing of Twain's death, President William Howard Taft said:[54][55]

- "Mark Twain gave pleasure – real intellectual enjoyment – to millions, and his works will continue to give such pleasure to millions yet to come ... His humor was American, but he was nearly as much appreciated by Englishmen and people of other countries as by his own countrymen. He has made an enduring part of American literature."

Officials in Connecticut and New York estimated the value of Twain's estate at $471,000 ($12,000,000 today); his manuscripts were given no monetary value, and his copyrights given little and decreasing value.[58]

Writing

Overview

Mark Twain in his gown (scarlet with grey sleeves and facings) for his D.Litt. degree, awarded to him by Oxford University

Twain began his career writing light, humorous verse, but evolved into a chronicler of the vanities, hypocrisies and murderous acts of mankind. At mid-career, with Huckleberry Finn, he combined rich humor, sturdy narrative and social criticism. Twain was a master at rendering colloquial speech and helped to create and popularize a distinctive American literature built on American themes and language. Many of Twain's works have been suppressed at times for various reasons. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has been repeatedly restricted in American high schools, not least for its frequent use of the word "nigger," which was in common usage in the pre-Civil War period in which the novel was set.

A complete bibliography of his works is nearly impossible to compile because of the vast number of pieces written by Twain (often in obscure newspapers) and his use of several different pen names. Additionally, a large portion of his speeches and lectures have been lost or were not written down; thus, the collection of Twain's works is an ongoing process. Researchers rediscovered published material by Twain as recently as 1995.[38]

Early journalism and travelogues

Cabin where Twain wrote "Jumping Frog of Calaveras County," Jackass Hill, Tuolumne County. Click on historical marker and interior view.

While writing for the Virginia City newspaper, the Territorial Enterprise in 1863, Clemens met lawyer Tom Fitch, editor of the competing newspaper Virginia Daily Union and known as the "silver-tongued orator of the Pacific."[59]:51 He credited Fitch with giving him his "first really profitable lesson" in writing. In 1866, Clemens presented his lecture on the Sandwich Islands to a crowd in Washoe City, Nevada.[60] Clemens commented that, "When I first began to lecture, and in my earlier writings, my sole idea was to make comic capital out of everything I saw and heard." Fitch told him, "Clemens, your lecture was magnificent. It was eloquent, moving, sincere. Never in my entire life have I listened to such a magnificent piece of descriptive narration. But you committed one unpardonable sin—the unpardonable sin. It is a sin you must never commit again. You closed a most eloquent description, by which you had keyed your audience up to a pitch of the intensest interest, with a piece of atrocious anti-climax which nullified all the really fine effect you had produced."[61] It was in these days that Twain became a writer of the Sagebrush School, and was known later as the most notable within this literary genre.[62]

Twain's first important work, "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County," was first published in the New York Saturday Press on November 18, 1865. The only reason it was published there was that his story arrived too late to be included in a book Artemus Ward was compiling featuring sketches of the wild American West.

After this burst of popularity, the Sacramento Union commissioned Twain to write letters about his travel experiences. The first journey he took for this job was to ride the steamer Ajax in its maiden voyage to Hawaii, referred to at the time as the Sandwich Islands. These humorous letters proved the genesis to his work with the San Francisco Alta California newspaper, which designated him a traveling correspondent for a trip from San Francisco to New York City via the Panama isthmus. All the while, Twain was writing letters meant for publishing back and forth, chronicling his experiences with his burlesque humor. On June 8, 1867, Twain set sail on the pleasure cruiser Quaker City for five months. This trip resulted in The Innocents Abroad or The New Pilgrims' Progress.

This book is a record of a pleasure trip. If it were a record of a solemn scientific expedition it would have about it the gravity, that profundity, and that impressive incomprehensibility which are so proper to works of that kind, and withal so attractive. Yet not withstanding it is only a record of a picnic, it has a purpose, which is, to suggest to the reader how he would be likely to see Europe and the East if he looked at them with his own eyes instead of the eyes of those who traveled in those countries before him. I make small pretense of showing anyone how he ought to look at objects of interest beyond the sea—other books do that, and therefore, even if I were competent to do it, there is no need.In 1872, Twain published a second piece of travel literature, Roughing It, as a semi-sequel to Innocents. Roughing It is a semi-autobiographical account of Twain's journey from Missouri to Nevada, his subsequent life in the American West, and his visit to Hawaii. The book lampoons American and Western society in the same way that Innocents critiqued the various countries of Europe and the Middle East. Twain's next work kept Roughing It's focus on American society but focused more on the events of the day. Entitled The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, it was not a travel piece, as his previous two books had been, and it was his first attempt at writing a novel. The book is also notable because it is Twain's only collaboration; it was written with his neighbor Charles Dudley Warner.

Twain's next two works drew on his experiences on the Mississippi River. Old Times on the Mississippi, a series of sketches published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1875, featured Twain's disillusionment with Romanticism.[63] Old Times eventually became the starting point for Life on the Mississippi.

Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn

Twain's next major publication was The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, which drew on his youth in Hannibal. Tom Sawyer was modeled on Twain as a child, with traces of two schoolmates, John Briggs and Will Bowen. The book also introduced in a supporting role Huckleberry Finn, based on Twain's boyhood friend Tom Blankenship.The Prince and the Pauper, despite a storyline that is omnipresent in film and literature today, was not as well received. Telling the story of two boys born on the same day who are physically identical, the book acts as a social commentary as the prince and pauper switch places. Pauper was Twain's first attempt at historical fiction, and blame for its shortcomings is usually put on Twain for having not been experienced enough in English society, and also on the fact that it was produced after a massive hit. In between the writing of Pauper, Twain had started Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (which he consistently had problems completing[64]) and started and completed another travel book, A Tramp Abroad, which follows Twain as he traveled through central and southern Europe.

Twain's next major published work, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, solidified him as a noteworthy American writer. Some have called it the first Great American Novel, and the book has become required reading in many schools throughout the United States. Huckleberry Finn was an offshoot from Tom Sawyer and had a more serious tone than its predecessor. The main premise behind Huckleberry Finn is the young boy's belief in the right thing to do though most believed that it was wrong. Four hundred manuscript pages of Huckleberry Finn were written in mid-1876, right after the publication of Tom Sawyer. Some accounts have Twain taking seven years off after his first burst of creativity, eventually finishing the book in 1883. Other accounts have Twain working on Huckleberry Finn in tandem with The Prince and the Pauper and other works in 1880 and other years. The last fifth of Huckleberry Finn is subject to much controversy. Some say that Twain experienced, as critic Leo Marx puts it, a "failure of nerve." Ernest Hemingway once said of Huckleberry Finn:

If you read it, you must stop where the Nigger Jim is stolen from the boys. That is the real end. The rest is just cheating.Hemingway also wrote in the same essay:

All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.[65]Near the completion of Huckleberry Finn, Twain wrote Life on the Mississippi, which is said to have heavily influenced the former book.[38] The work recounts Twain's memories and new experiences after a 22-year absence from the Mississippi. In it, he also states that "Mark Twain" was the call made when the boat was in safe water – two fathoms (12 feet or 3.7 metres).

Later writing

After his great work, Twain began turning to his business endeavors to keep them afloat and to stave off the increasing difficulties he had been having from his writing projects. Twain focused on President Ulysses S. Grant's Memoirs for his fledgling publishing company, finding time in between to write "The Private History of a Campaign That Failed" for The Century Magazine. This piece detailed his two-week stint in a Confederate militia during the Civil War. The name of his publishing company was Charles L. Webster & Company, which he owned with Charles L. Webster, his nephew by marriage.[66]Twain next focused on A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, which featured him making his first big pronouncement of disappointment with politics. Written with the same historical fiction style of The Prince and the Pauper, A Connecticut Yankee showed the absurdities of political and social norms by setting them in the court of King Arthur. The book was started in December 1885, then shelved a few months later until the summer of 1887, and eventually finished in the spring of 1889.

To pay the bills and keep his business projects afloat, Twain had begun to write articles and commentary furiously, with diminishing returns, but it was not enough. He filed for bankruptcy in 1894.

His next large-scale work, Pudd'nhead Wilson, was written rapidly, as Twain was desperately trying to stave off the bankruptcy. From November 12 to December 14, 1893, Twain wrote 60,000 words for the novel.[38] Critics have pointed to this rushed completion as the cause of the novel's rough organization and constant disruption of continuous plot. There were parallels between this work and Twain's financial failings, notably his desire to escape his current constraints and become a different person.

Like The Prince and the Pauper, this novel also contains the tale of two boys born on the same day who switch positions in life. Considering the circumstances of Twain's birth and Halley's Comet, and his strong belief in the paranormal, it is not surprising that these "mystic" connections recur throughout his writing.

The actual title is not clearly established. It was first published serially in Century Magazine, and when it was finally published in book form, Pudd'nhead Wilson appeared as the main title; however, the disputed "subtitles" make the entire title read: The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson and the Comedy of The Extraordinary Twins.[38]

Twain's next venture was a work of straight fiction that he called Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc and dedicated to his wife. Twain had long said that this was the work he was most proud of, despite the criticism he received for it. The book had been a dream of his since childhood. He claimed he had found a manuscript detailing the life of Joan of Arc when he was an adolescent.[38]

This was another piece Twain was convinced would save his publishing company. His financial adviser, Henry Huttleston Rogers, quashed that idea and got Twain out of that business altogether, but the book was published nonetheless.

During this time of dire financial straits, Twain published several literary reviews in newspapers to help make ends meet. He famously derided James Fenimore Cooper in his article detailing Cooper's "Literary Offenses." He became an extremely outspoken critic of not only other authors, but also other critics, suggesting that before praising Cooper's work, Thomas Lounsbury, Brander Matthews, and Wilkie Collins "ought to have read some of it."[67]

Other authors to fall under Twain's attack during this time period (beginning around 1890 until his death) were George Eliot, Jane Austen, and Robert Louis Stevenson.[68] In addition to providing a source for the "tooth and claw" style of literary criticism, Twain outlines in several letters and essays what he considers to be "quality writing." He places emphasis on concision, utility of word choice, and realism (he complains that Cooper's Deerslayer purports to be realistic but has several shortcomings). Ironically, several of his works were later criticized for lack of continuity (Adventures of Huckleberry Finn) and organization (Pudd'nhead Wilson).

Twain's wife died in 1904 while the couple were staying at the Villa di Quarto in Florence; and, after an appropriate period of time, Twain allowed himself to publish some works that his wife, a de facto editor and censor throughout his life, had looked down upon. Of these works, The Mysterious Stranger, depicting various visits of Satan to the Earth, is perhaps the best known. This particular work was not published in Twain's lifetime. There were three versions found in his manuscripts, made between 1897 and 1905: the Hannibal, Eseldorf, and Print Shop versions. Confusion among the versions led to an extensive publication of a jumbled version, and only recently have the original versions as Twain wrote them become available.

Twain's last work was his autobiography, which he dictated and thought would be most entertaining if he went off on whims and tangents in non-chronological order. Some archivists and compilers have rearranged the biography into more conventional forms, thereby eliminating some of Twain's humor and the flow of the book. The first volume of autobiography, over 736 pages, was published by the University of California in November 2010, 100 years after his death, as Twain wished.[69][70] It soon became an unexpected[71] best seller,[72] making Twain one of very few authors publishing new best-selling volumes in all three of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.

Censorship

Twain’s works have been subjected to censorship efforts. According to Stuart (2013) “Leading these banning campaigns, generally, were religious organizations or individuals in positions of influence – not so much working librarians, who had been instilled with that American “library spirit” which honored intellectual freedom (within bounds of course). In 1905, the Brooklyn Public Library banned both The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer from the children's department because of their language.[73]Views

Twain's views became more radical as he grew older. He acknowledged that his views changed and developed over his life, referring to one of his favorite works:When I finished Carlyle's French Revolution in 1871, I was a Girondin; every time I have read it since, I have read it differently—being influenced and changed, little by little, by life and environment ... and now I lay the book down once more, and recognize that I am a Sansculotte! And not a pale, characterless Sansculotte, but a Marat.[74]

Anti-imperialist

In the New York Herald, October 15, 1900, he describes his transformation and political awakening, in the context of the Philippine-American War, from being "a red-hot imperialist":I wanted the American eagle to go screaming into the Pacific ... Why not spread its wings over the Philippines, I asked myself? ... I said to myself, Here are a people who have suffered for three centuries. We can make them as free as ourselves, give them a government and country of their own, put a miniature of the American Constitution afloat in the Pacific, start a brand new republic to take its place among the free nations of the world. It seemed to me a great task to which we had addressed ourselves.Before 1899, Twain was an ardent imperialist. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, he spoke out strongly in favor of American interests in the Hawaiian Islands.[76] In the mid-1890s he explained later, he was "a red-hot imperialist. I wanted the American eagle to go screaming over the Pacific."[77]

But I have thought some more, since then, and I have read carefully the treaty of Paris [which ended the Spanish-American War], and I have seen that we do not intend to free, but to subjugate the people of the Philippines. We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem.

It should, it seems to me, be our pleasure and duty to make those people free, and let them deal with their own domestic questions in their own way. And so I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.[75]

He said the war with Spain in 1898 was "the worthiest" war ever fought.[78] In 1899, he reversed course, and from 1901, soon after his return from Europe, until his death in 1910, Twain was vice-president of the American Anti-Imperialist League,[79] which opposed the annexation of the Philippines by the United States and had "tens of thousands of members."[30] He wrote many political pamphlets for the organization. The Incident in the Philippines, posthumously published in 1924, was in response to the Moro Crater Massacre, in which six hundred Moros were killed. Many of his neglected and previously uncollected writings on anti-imperialism appeared for the first time in book form in 1992.[79]

Twain was critical of imperialism in other countries as well. In Following the Equator, Twain expresses "hatred and condemnation of imperialism of all stripes."[30] He was highly critical of European imperialism, notably of Cecil Rhodes, who greatly expanded the British Empire, and of Leopold II, King of the Belgians.[30] King Leopold's Soliloquy is a stinging political satire about his private colony, the Congo Free State. Reports of outrageous exploitation and grotesque abuses led to widespread international protest in the early 1900s, arguably the first large-scale human rights movement. In the soliloquy, the King argues that bringing Christianity to the country outweighs a little starvation. Leopold's rubber gatherers were tortured, maimed and slaughtered, until the movement forced Brussels to call a halt.[80][81]

During the Philippine-American War, Twain wrote a short pacifist story entitled The War Prayer, which makes the point that humanism and Christianity's preaching of love are incompatible with the conduct of war. It was submitted to Harper's Bazaar for publication, but on March 22, 1905, the magazine rejected the story as "not quite suited to a woman's magazine." Eight days later, Twain wrote to his friend Daniel Carter Beard, to whom he had read the story, "I don't think the prayer will be published in my time. None but the dead are permitted to tell the truth." Because he had an exclusive contract with Harper & Brothers, Twain could not publish The War Prayer elsewhere; it remained unpublished until 1923. It was republished as campaigning material by Vietnam War protesters.[30]

Twain acknowledged he originally sympathized with the more moderate Girondins of the French Revolution and then shifted his sympathies to the more radical Sansculottes, indeed identifying as "a Marat." Twain supported the revolutionaries in Russia against the reformists, arguing that the Tsar must be got rid of, by violent means, because peaceful ones would not work.[82] He summed up his views of revolutions in the following statement:

I am said to be a revolutionist in my sympathies, by birth, by breeding and by principle. I am always on the side of the revolutionists, because there never was a revolution unless there were some oppressive and intolerable conditions against which to revolute.[83]

Civil rights

Twain was an adamant supporter of the abolition of slavery and emancipation of slaves, even going so far to say "Lincoln's Proclamation ... not only set the black slaves free, but set the white man free also."[84] He argued that non-whites did not receive justice in the United States, once saying "I have seen Chinamen abused and maltreated in all the mean, cowardly ways possible to the invention of a degraded nature ... but I never saw a Chinaman righted in a court of justice for wrongs thus done to him."[85] He paid for at least one black person to attend Yale Law School and for another black person to attend a southern university to become a minister.[86]Twain's views on race were not reflected in his early sketches of Native Americans. Of them, Twain wrote in 1870:

His heart is a cesspool of falsehood, of treachery, and of low and devilish instincts. With him, gratitude is an unknown emotion; and when one does him a kindness, it is safest to keep the face toward him, lest the reward be an arrow in the back. To accept of a favor from him is to assume a debt which you can never repay to his satisfaction, though you bankrupt yourself trying. The scum of the earth![87]As counterpoint, Twain's essay on "The Literary Offenses of Fenimore Cooper" offers a much kinder view of Indians.[67] "No, other Indians would have noticed these things, but Cooper's Indians never notice anything. Cooper thinks they are marvelous creatures for noticing, but he was almost always in error about his Indians. There was seldom a sane one among them."[88] In his later travelogue Following the Equator (1897), Twain observes that in colonized lands all over the world, "savages" have always been wronged by "whites" in the most merciless ways, such as "robbery, humiliation, and slow, slow murder, through poverty and the white man's whiskey"; his conclusion is that "there are many humorous things in this world; among them the white man's notion that he is less savage than the other savages.".[89] In an expression that captures his Indian experiences, he wrote, “So far as

I am able to judge nothing has been left undone, either by man or Nature, to make India the most extraordinary country that the sun visits on his rounds. Where every prospect pleases, and only man is vile.”[90]

Twain was also a staunch supporter of women's rights and an active campaigner for women's suffrage. His "Votes for Women" speech, in which he pressed for the granting of voting rights to women, is considered one of the most famous in history.[91]

Helen Keller benefited from Twain's support, as she pursued her college education and publishing, despite her disabilities and financial limitations.

Labor

Twain wrote glowingly about unions in the river boating industry in Life on the Mississippi, which was read in union halls decades later.[92] He supported the labor movement, especially one of the most important unions, the Knights of Labor.[30] In a speech to them, he said:Who are the oppressors? The few: the King, the capitalist, and a handful of other overseers and superintendents. Who are the oppressed? The many: the nations of the earth; the valuable personages; the workers; they that make the bread that the soft-handed and idle eat.[93]

Vivisection

Twain was opposed to the vivisection practices of his day. His objection was not on a scientific basis but rather an ethical one. He specifically cited the pain caused to the animal as his basis of his opposition.[94]I am not interested to know whether vivisection produces results that are profitable to the human race or doesn't. ... The pain which it inflicts upon unconsenting animals is the basis of my enmity toward it, and it is to me sufficient justification of the enmity without looking further.

Religion

Although Twain was a Presbyterian, he was sometimes critical of organized religion and certain elements of Christianity through his later life. He wrote, for example, "Faith is believing what you know ain't so," and "If Christ were here now there is one thing he would not be—a Christian."[95] Nonetheless, as a mature adult he engaged in religious discussions and attended services, his theology developing as he wrestled with the deaths of loved ones and his own mortality.[96] His own experiences and suffering within his family made him particularly critical of "faith healing," such as espoused by Mary Baker Eddy and Christian Science.[citation needed]Twain generally avoided publishing his most heretical opinions on religion in his lifetime, and they are known from essays and stories that were published later. In the essay Three Statements of the Eighties in the 1880s, Twain stated that he believed in an almighty God, but not in any messages, revelations, holy scriptures such as the Bible, Providence, or retribution in the afterlife. He did state that "the goodness, the justice, and the mercy of God are manifested in His works," but also that "the universe is governed by strict and immutable laws," which determine "small matters," such as who dies in a pestilence.[97] At other times he wrote or spoke in ways that contradicted a strict deist view, for example, plainly professing a belief in Providence.[98] In some later writings in the 1890s, he was less optimistic about the goodness of God, observing that "if our Maker is all-powerful for good or evil, He is not in His right mind." At other times, he conjectured sardonically that perhaps God had created the world with all its tortures for some purpose of His own, but was otherwise indifferent to humanity, which was too petty and insignificant to deserve His attention anyway.[99]

In 1901 Twain criticized the actions of missionary Dr. William Scott Ament (1851–1909) because Ament and other missionaries had collected indemnities from Chinese subjects in the aftermath of the Boxer Uprising of 1900. Twain's response to hearing of Ament's methods was published in the North American Review in February 1901: To the Person Sitting in Darkness, and deals with examples of imperialism in China, South Africa, and with the U.S. occupation of the Philippines.[100] A subsequent article, "To My Missionary Critics" published in The North American Review in April 1901, unapologetically continues his attack, but with the focus shifted from Ament to his missionary superiors, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions.[101]

After his death, Twain's family suppressed some of his work that was especially irreverent toward conventional religion, notably Letters from the Earth, which was not published until his daughter Clara reversed her position in 1962 in response to Soviet propaganda about the withholding.[102] The anti-religious The Mysterious Stranger was published in 1916. Little Bessie, a story ridiculing Christianity, was first published in the 1972 collection Mark Twain's Fables of Man.[103]

Despite these views, he raised money to build a Presbyterian Church in Nevada in 1864, although it has been argued that it was only by his association with his Presbyterian brother that he did that.[104]

Twain created a reverent portrayal of Joan of Arc, a subject over which he had obsessed for forty years, studied for a dozen years and spent two years writing.[105] In 1900 and again in 1908, he stated, "I like Joan of Arc best of all my books, it is the best." [105][106]

Those who knew Twain well late in life recount that he dwelt on the subject of the afterlife, his daughter Clara saying: "Sometimes he believed death ended everything, but most of the time he felt sure of a life beyond."[107]

Twain's frankest views on religion appeared in his final work Autobiography of Mark Twain, the publication of which started in November 2010, 100 years after his death. In it, he said:[108]

There is one notable thing about our Christianity: bad, bloody, merciless, money-grabbing, and predatory as it is—in our country particularly and in all other Christian countries in a somewhat modified degree—it is still a hundred times better than the Christianity of the Bible, with its prodigious crime—the invention of Hell. Measured by our Christianity of to-day, bad as it is, hypocritical as it is, empty and hollow as it is, neither the Deity nor his Son is a Christian, nor qualified for that moderately high place. Ours is a terrible religion. The fleets of the world could swim in spacious comfort in the innocent blood it has spilled.Twain was a Freemason.[109][110] He belonged to Polar Star Lodge No. 79 A.F.&A.M., based in St. Louis. He was initiated an Entered Apprentice on May 22, 1861, passed to the degree of Fellow Craft on June 12, and raised to the degree of Master Mason on July 10.

Pen names

Twain used different pen names before deciding on "'Mark Twain". He signed humorous and imaginative sketches as "Josh" until 1863. Additionally, he used the pen name "Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass" for a series of humorous letters.[111]He maintained that his primary pen name came from his years working on Mississippi riverboats, where two fathoms, a depth indicating safe water for passage of boat, was measured on the sounding line. Twain is an archaic term for "two", as in "The veil of the temple was rent in twain." [112] The riverboatman's cry was "mark twain" or, more fully, "by the mark twain", meaning "according to the mark [on the line], [the depth is] two [fathoms]," that is, "The water is 12 feet (3.7 m) deep and it is safe to pass."

Twain claimed that his famous pen name was not entirely his invention. In Life on the Mississippi, he wrote:

Captain Isaiah Sellers was not of literary turn or capacity, but he used to jot down brief paragraphs of plain practical information about the river, and sign them "MARK TWAIN," and give them to the New Orleans Picayune. They related to the stage and condition of the river, and were accurate and valuable; ... At the time that the telegraph brought the news of his death, I was on the Pacific coast. I was a fresh new journalist, and needed a nom de guerre; so I confiscated the ancient mariner's discarded one, and have done my best to make it remain what it was in his hands – a sign and symbol and warrant that whatever is found in its company may be gambled on as being the petrified truth; how I have succeeded, it would not be modest in me to say.[113]Twain's story about his pen name has been questioned by biographer George Williams III,[114] the Territorial Enterprise newspaper,[115] and Purdue University's Paul Fatout.[116] The claim is that "mark twain" refers to a running bar tab that Twain would regularly incur while drinking at John Piper's saloon in Virginia City, Nevada.

Legacy

Twain's legacy lives on today as his namesakes continue to multiply. Several schools are named after him, including Mark Twain Elementary School in Wheeling, Illinois, and Mark Twain Elementary School in Houston, Texas, which has a statue of Twain sitting on a bench. There is also Mark Twain Intermediate School in New York. There are several schools named Mark Twain Middle School in different states, as well as Samuel Clemens High School in Schertz, near San Antonio, Texas. There are also other structures, such as the Mark Twain Memorial Bridge.

Mark Twain Village is a United States Army installation located in the Südstadt district of Heidelberg, Germany. It is one of two American bases in the United States Army Garrison Heidelberg that house American soldiers and their families (the other being Patrick Henry Village).

Awards in his name proliferate. In 1998, The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts created the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor, awarded annually. The Mark Twain Award is an award given annually to a book for children in grades four through eight by the Missouri Association of School Librarians. Stetson University in DeLand, Florida sponsors the Mark Twain Young Authors' Workshop each summer in collaboration with the Mark Twain Boyhood Home & Museum in Hannibal. The program is open to young authors in grades five through eight.[117] The museum sponsors the Mark Twain Creative Teaching Award.[118]

Buildings associated with Twain, including some of his many homes, have been preserved as museums. His birthplace is preserved in Florida, Missouri. The Mark Twain Boyhood Home & Museum in Hannibal, Missouri preserves the setting for some of the author's best known work. The home of childhood friend Laura Hawkins, said to be the inspiration for his fictional character Becky Thatcher, is preserved as the "Thatcher House." In May 2007, a painstaking reconstruction of the home of Tom Blankenship, the inspiration for Huckleberry Finn, was opened to the public. The family home he had built in Hartford, Connecticut, where he and his wife raised their three daughters, is preserved and open to visitors as the Mark Twain House.

Asteroid 2362 Mark Twain was named after him.

On December 4, 1985, the United States Postal Service issued a stamped envelope for "Mark Twain and Halley's Comet," noting the connection with Twain's birth, his death, and the comet.[119] On June 25, 2011, the Postal Service released a Forever stamp in his honor.[120]

Depictions

Twain is often depicted wearing a white suit. While there is evidence that suggests that, after Livy's death in 1904, Twain began wearing white suits on the lecture circuit, modern representations suggesting that he wore them throughout his life are unfounded. However, there is evidence showing him wearing a white suit before 1904. In 1882, he sent a photograph of himself in a white suit to 18-year-old Edward W. Bok, later publisher of the Ladies Home Journal, with a handwritten dated note on verso. It did eventually become his trademark, as illustrated in anecdotes about this eccentricity (such as the time he wore a white summer suit to a Congressional hearing during the winter).[38] McMasters' The Mark Twain Encyclopedia states that Twain did not wear a white suit in his last three years, except at one banquet speech.[121]Actor Hal Holbrook created a one-man show called Mark Twain Tonight, which he has performed regularly for about 59 years.[122] The broadcast by CBS in 1967 won him an Emmy Award. Of the three runs on Broadway (1966, 1977, and 2005), the first won him a Tony Award.

Twain was portrayed by Fredric March in the 1944 film The Adventures of Mark Twain. He was later brought to life by James Whitmore in the (similarly titled) 1985 Will Vinton Claymation film The Adventures of Mark Twain. In the two-part Star Trek: The Next Generation episode, "Time's Arrow Pt. 1 & 2", the crew of the starship Enterprise pursues malevolent alien lifeforms through a time portal to 1893 San Francisco, where their secretive actions arouse the suspicions of Samuel Clemens as played by Jerry Hardin.