Theory

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

One modern group of meanings emphasizes the interpretative, abstracting, and generalizing nature of theory. For example in the arts and philosophy, the term "theoretical" may be used to describe ideas and empirical phenomena which are not easily measurable. Theory abstracts. It draws away from the particular and empirical. By extension of the philosophical meaning, "theoria" is a word still used in theological contexts to mean viewing through contemplation — speculating about meanings that transcend measurement. However, by contrast to theoria, theory is based on the act of viewing analytically and generalizing contextually. It is thus based upon a process of abstraction. That is, theory involves stepping back, or abstracting, from that which one is viewing.[1]

A theory can be normative (or prescriptive),[2] meaning a postulation about what ought to be. It provides "goals, norms, and standards".[3] A theory can be a body of knowledge, which may or may not be associated with particular explanatory models. To theorize is to develop this body of knowledge.[4]

As already in Aristotle's definitions, theory is very often contrasted to "practice" (from Greek praxis, πρᾶξις) a Greek term for "doing", which is opposed to theory because pure theory involves no doing apart from itself. A classical example of the distinction between "theoretical" and "practical" uses the discipline of medicine: medical theory involves trying to understand the causes and nature of health and sickness, while the practical side of medicine is trying to make people healthy. These two things are related but can be independent, because it is possible to research health and sickness without curing specific patients, and it is possible to cure a patient without knowing how the cure worked.[5]

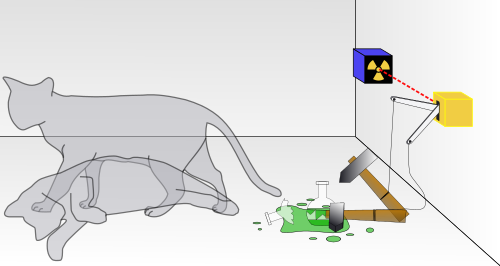

In modern science, the term "theory" refers to scientific theories, a well-confirmed type of explanation of nature, made in a way consistent with scientific method, and fulfilling the criteria required by modern science. Such theories are described in such a way that any scientist in the field is in a position to understand and either provide empirical support ("verify") or empirically contradict ("falsify") it. Scientific theories are the most reliable, rigorous, and comprehensive form of scientific knowledge,[6] in contrast to more common uses of the word "theory" that imply that something is unproven or speculative (which is better characterized by the word 'hypothesis').[7] Scientific theories are distinguished from hypotheses, which are individual empirically testable conjectures, and scientific laws, which are descriptive accounts of how nature will behave under certain conditions.[8]

Ancient uses

The English word theory was derived from a technical term in philosophy in Ancient Greek. As an everyday word, theoria, θεωρία, meant "a looking at, viewing, beholding", but in more technical contexts it came to refer to contemplative or speculative understandings of natural things, such as those of natural philosophers, as opposed to more practical ways of knowing things, like that of skilled orators or artisans.[9] The word has been in use in English since at least the late 16th century.[10] Modern uses of the word "theory" are derived from the original definition, but have taken on new shades of meaning, still based on the idea that a theory is a thoughtful and rational explanation of the general nature of things.Although it has more mundane meanings in Greek, the word θεωρία apparently developed special uses early in the recorded history of the Greek language. In the book From Religion to Philosophy, Francis Cornford suggests that the Orphics used the word "theory" to mean 'passionate sympathetic contemplation'.[11] Pythagoras changed the word to mean a passionate sympathetic contemplation of mathematical knowledge, because he considered this intellectual pursuit the way to reach the highest plane of existence. Pythagoras emphasized subduing emotions and bodily desires in order to enable the intellect to function at the higher plane of theory. Thus it was Pythagoras who gave the word "theory" the specific meaning which leads to the classical and modern concept of a distinction between theory as uninvolved, neutral thinking, and practice.[12]

In Aristotle's terminology, as has already been mentioned above, theory is contrasted with praxis or practice, which remains the case today. For Aristotle, both practice and theory involve thinking, but the aims are different. Theoretical contemplation considers things which humans do not move or change, such as nature, so it has no human aim apart from itself and the knowledge it helps create. On the other hand, praxis involves thinking, but always with an aim to desired actions, whereby humans cause change or movement themselves for their own ends. Any human movement which involves no conscious choice and thinking could not be an example of praxis or doing.[13]

Theories formally and scientifically

Theories are analytical tools for understanding, explaining, and making predictions about a given subject matter. There are theories in many and varied fields of study, including the arts and sciences.A formal theory is syntactic in nature and is only meaningful when given a semantic component by applying it to some content (i.e. facts and relationships of the actual historical world as it is unfolding). Theories in various fields of study are expressed in natural language, but are always constructed in such a way that their general form is identical to a theory as it is expressed in the formal language of mathematical logic. Theories may be expressed mathematically, symbolically, or in common language, but are generally expected to follow principles of rational thought or logic.

Theory is constructed of a set of sentences which consist entirely of true statements about the subject matter under consideration. However, the truth of any one of these statements is always relative to the whole theory. Therefore the same statement may be true with respect to one theory, and not true with respect to another. This is, in ordinary language, where statements such as "He is a terrible person" cannot be judged to be true or false without reference to some interpretation of who "He" is and for that matter what a "terrible person" is under the theory.[14]

Sometimes two theories have exactly the same explanatory power because they make the same predictions. A pair of such theories is called indistinguishable, and the choice between them reduces to convenience or philosophical preference.

The form of theories is studied formally in mathematical logic, especially in model theory. When theories are studied in mathematics, they are usually expressed in some formal language and their statements are closed under application of certain procedures called rules of inference. A special case of this, an axiomatic theory, consists of axioms (or axiom schemata) and rules of inference. A theorem is a statement that can be derived from those axioms by application of these rules of inference. Theories used in applications are abstractions of observed phenomena and the resulting theorems provide solutions to real-world problems. Obvious examples include arithmetic (abstracting concepts of number), geometry (concepts of space), and probability (concepts of randomness and likelihood).

Gödel's incompleteness theorem shows that no consistent, recursively enumerable theory (that is, one whose theorems form a recursively enumerable set) in which the concept of natural numbers can be expressed, can include all true statements about them. As a result, some domains of knowledge cannot be formalized, accurately and completely, as mathematical theories. (Here, formalizing accurately and completely means that all true propositions—and only true propositions—are derivable within the mathematical system.) This limitation, however, in no way precludes the construction of mathematical theories that formalize large bodies of scientific knowledge.

Underdetermination

A theory is underdetermined (also called indeterminacy of data to theory) if, given the available evidence cited to support the theory, there is a rival theory which is inconsistent with it that is at least as consistent with the evidence. Underdetermination is an epistemological issue about the relation of evidence to conclusions.Intertheoretic reduction and elimination

If there is a new theory which is better at explaining and predicting phenomena than an older theory (i.e. it has more explanatory power), we are justified in believing that the newer theory describes reality more correctly. This is called an intertheoretic reduction because the terms of the old theory can be reduced to the terms of the new one. For instance, our historical understanding about "sound", "light" and "heat" have today been reduced to "wave compressions and rarefactions", "electromagnetic waves", and "molecular kinetic energy", respectively. These terms which are identified with each other are called intertheoretic identities. When an old theory and a new one are parallel in this way, we can conclude that we are describing the same reality, only more completely.In cases where a new theory uses new terms which do not reduce to terms of an older one, but rather replace them entirely because they are actually a misrepresentation it is called an intertheoretic elimination. For instance, the obsolete scientific theory that put forward an understanding of heat transfer in terms of the movement of caloric fluid was eliminated when a theory of heat as energy replaced it. Also, the theory that phlogiston is a substance released from burning and rusting material was eliminated with the new understanding of the reactivity of oxygen.

Theories vs. theorems

Theories are distinct from theorems. Theorems are derived deductively from objections according to a formal system of rules, sometimes as an end in itself and sometimes as a first step in testing or applying a theory in a concrete situation; theorems are said to be true in the sense that the conclusions of a theorem are logical consequences of the objections. Theories are abstract and conceptual, and to this end they are always considered true. They are supported or challenged by observations in the world. They are 'rigorously tentative', meaning that they are proposed as true and expected to satisfy careful examination to account for the possibility of faulty inference or incorrect observation.Sometimes theories are incorrect, meaning that an explicit set of observations contradicts some fundamental objection or application of the theory, but more often theories are corrected to conform to new observations, by restricting the class of phenomena the theory applies to or changing the assertions made. An example of the former is the restriction of Classical mechanics to phenomena involving macroscopic lengthscales and particle speeds much lower than the speed of light.

"Sometimes a hypothesis never reaches the point of being considered a theory because the answer is not found to derive its assertions analytically or not applied empirically."[citation needed]

Philosophical theories

Theories whose subject matter consists not in empirical data, but rather in ideas are in the realm of philosophical theories as contrasted with scientific theories. At least some of the elementary theorems of a philosophical theory are statements whose truth cannot necessarily be scientifically tested through empirical observation.Fields of study are sometimes named "theory" because their basis is some initial set of objections describing the field's approach to a subject matter. These assumptions are the elementary theorems of the particular theory, and can be thought of as the axioms of that field. Some commonly known examples include set theory and number theory; however literary theory, critical theory, and music theory are also of the same form.

Metatheory

One form of philosophical theory is a metatheory or meta-theory. A metatheory is a theory whose subject matter is some other theory. In other words it is a theory about a theory. Statements made in the metatheory about the theory are called metatheorems.Political theories

A political theory is an ethical theory about the law and government. Often the term "political theory" refers to a general view, or specific ethic, political belief or attitude, about politics.Scientific theories

In science, the term "theory" refers to "a well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the natural world, based on a body of facts that have been repeatedly confirmed through observation and experiment."[15][16] Theories must also meet further requirements, such as the ability to make falsifiable predictions with consistent accuracy across a broad area of scientific inquiry, and production of strong evidence in favor of the theory from multiple independent sources. (See characteristics of scientific theories.)The strength of a scientific theory is related to the diversity of phenomena it can explain, which is measured by its ability to make falsifiable predictions with respect to those phenomena. Theories are improved (or replaced by better theories) as more evidence is gathered, so that accuracy in prediction improves over time; this increased accuracy corresponds to an increase in scientific knowledge. Scientists use theories as a foundation to gain further scientific knowledge, as well as to accomplish goals such as inventing technology or curing disease.

Definitions from scientific organizations

The United States National Academy of Sciences defines scientific theories as follows:The formal scientific definition of "theory" is quite different from the everyday meaning of the word. It refers to a comprehensive explanation of some aspect of nature that is supported by a vast body of evidence. Many scientific theories are so well established that no new evidence is likely to alter them substantially. For example, no new evidence will demonstrate that the Earth does not orbit around the sun (heliocentric theory), or that living things are not made of cells (cell theory), that matter is not composed of atoms, or that the surface of the Earth is not divided into solid plates that have moved over geological timescales (the theory of plate tectonics)...One of the most useful properties of scientific theories is that they can be used to make predictions about natural events or phenomena that have not yet been observed.[17]From the American Association for the Advancement of Science:

A scientific theory is a well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the natural world, based on a body of facts that have been repeatedly confirmed through observation and experiment. Such fact-supported theories are not "guesses" but reliable accounts of the real world. The theory of biological evolution is more than "just a theory." It is as factual an explanation of the universe as the atomic theory of matter or the germ theory of disease. Our understanding of gravity is still a work in progress. But the phenomenon of gravity, like evolution, is an accepted fact.[16]Note that the term theory would not be appropriate for describing untested but intricate hypotheses or even scientific models.

Philosophical views

The logical positivists thought of scientific theories as deductive theories - that a theory's content is based on some formal system of logic and on basic axioms. In a deductive theory, any sentence which is a logical consequence of one or more of the axioms is also a sentence of that theory.[14] This is called the received view of theories.In the semantic view of theories, which has largely replaced the received view,[18][19] theories are viewed as scientific models. A model is a logical framework intended to represent reality (a "model of reality"), similar to the way that a map is a graphical model that represents the territory of a city or country. In this approach, theories are a specific category of models which fulfill the necessary criteria.

In physics

In physics the term theory is generally used for a mathematical framework—derived from a small set of basic postulates (usually symmetries, like equality of locations in space or in time, or identity of electrons, etc.)—which is capable of producing experimental predictions for a given category of physical systems. One good example is classical electromagnetism, which encompasses results derived from gauge symmetry (sometimes called gauge invariance) in a form of a few equations called Maxwell's equations. The specific mathematical aspects of classical electromagnetic theory are termed "laws of electromagnetism", reflecting the level of consistent and reproducible evidence that supports them. Within electromagnetic theory generally, there are numerous hypotheses about how electromagnetism applies to specific situations. Many of these hypotheses are already considered to be adequately tested, with new ones always in the making and perhaps untested.The term theoretical

Acceptance of a theory does not require that all of its major predictions be tested, if it is already supported by sufficiently strong evidence. For example, certain tests may be unfeasible or technically difficult. As a result, theories may make predictions that have not yet been confirmed or proven incorrect; in this case, the predicted results may be described informally with the term "theoretical."These predictions can be tested at a later time, and if they are incorrect, this may lead to revision or rejection of the theory.

List of notable theories

- Astronomy: Big Bang Theory

- Biology: Cell theory — Evolution — Germ theory

- Chemistry: Molecular theory — Kinetic theory of gases — Molecular orbital theory — Valence bond theory — Transition state theory — RRKM theory — Chemical graph theory — Flory–Huggins solution theory — Marcus theory — Lewis theory (successor to Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory) — HSAB theory — Debye–Hückel theory — Thermodynamic theory of polymer elasticity — Reptation theory — Polymer field theory — Møller–Plesset perturbation theory — density functional theory — Frontier molecular orbital theory — Polyhedral skeletal electron pair theory — Baeyer strain theory — Quantum theory of atoms in molecules — Collision theory — Ligand field theory (successor to Crystal field theory) — Variational Transition State Theory — Benson group increment theory — Specific ion interaction theory

- Climatology: Climate change theory (general study of climate changes) and anthropogenic climate change (ACC)/ global warming (AGW) theories (due to human activity)

- Economics: Macroeconomic theory — Microeconomic theory - Law of Supply and demand

- Education: Constructivist theory — Critical pedagogy theory — Education theory — Multiple intelligence theory — Progressive education theory

- Engineering: Circuit theory — Control theory — Signal theory — Systems theory — Information theory

- Film: Film Theory

- Geology: Plate tectonics

- Humanities: Critical theory

- Linguistics: X-bar theory — Government and Binding — Principles and parameters - Universal grammar

- Literature: Literary theory

- Mathematics: Approximation theory — Arakelov theory — Asymptotic theory — Bifurcation theory — Catastrophe theory — Category theory — Chaos theory — Choquet theory — Coding theory — Combinatorial game theory — Computability theory — Computational complexity theory — Deformation theory — Dimension theory — Ergodic theory — Field theory — Galois theory — Game theory — Graph theory — Group theory — Hodge theory — Homology theory — Homotopy theory — Ideal theory — Intersection theory — Invariant theory — Iwasawa theory — K-theory — KK-theory — Knot theory — L-theory — Lie theory — Littlewood–Paley theory — Matrix theory — Measure theory — Model theory — Morse theory — Nevanlinna theory — Number theory — Obstruction theory — Operator theory — PCF theory — Perturbation theory — Potential theory — Probability theory — Ramsey theory — Rational choice theory — Representation theory — Ring theory — Set theory — Shape theory — Small cancellation theory — Spectral theory — Stability theory — Stable theory — Sturm–Liouville theory — Twistor theory

- Music: Music theory

- Philosophy: Proof theory — Speculative reason — Theory of truth — Type theory — Value theory — Virtue theory

- Physics: Acoustic theory — Antenna theory — Atomic theory — BCS theory — Dirac hole theory — Landau theory — M-theory — Perturbation theory — Theory of relativity (successor to classical mechanics) — Quantum field theory — Scattering theory — String theory

- Psychology: Theory of mind - Cognitive dissonance theory - Attachment theory - Object permanance - Poverty of stimulus - Attribution theory - Self-fulfilling prophecy - Stockholm syndrome

- Sociology: Critical theory — Engaged theory — Social theory — Sociological theory

- Statistics: Extreme value theory

- Theatre: Performance theory

- Visual Art: Aesthetics — Art Educational theory — Architecture — Composition — Anatomy — Color theory — Perspective — Visual perception — Geometry — Manifolds

- Other: Obsolete scientific theories