From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Gerard K. O'Neill | |

|---|---|

Gerard K. O'Neill in 1977

|

|

| Born | February 6, 1927 Brooklyn, New York, US |

| Died | April 27, 1992 (aged 65) Redwood City, California, US |

| Nationality | American |

| Fields | Physicist |

| Alma mater | Cornell University |

| Known for | Particle physics Space Studies Institute O'Neill cylinder |

Gerard Kitchen O'Neill (February 6, 1927 – April 27, 1992) was an American physicist and space activist. As a faculty member of Princeton University, he invented a device called the particle storage ring for high-energy physics experiments.[1] Later, he invented a magnetic launcher called the mass driver.[2] In the 1970s, he developed a plan to build human settlements in outer space, including a space habitat design known as the O'Neill cylinder. He founded the Space Studies Institute, an organization devoted to funding research into space manufacturing and colonization.

O'Neill began researching high-energy particle physics at Princeton in 1954, after he received his doctorate from Cornell University. Two years later, he published his theory for a particle storage ring. This invention allowed particle physics experiments at much higher energies than had previously been possible. In 1965 at Stanford University, he performed the first colliding beam physics experiment.[3]

While teaching physics at Princeton, O'Neill became interested in the possibility that humans could survive and live in outer space. He researched and proposed a futuristic idea for human settlement in space, the O'Neill cylinder, in "The Colonization of Space", his first paper on the subject. He held a conference on space manufacturing at Princeton in 1975. Many who became post-Apollo-era space activists attended. O'Neill built his first mass driver prototype with professor Henry Kolm in 1976. He considered mass drivers critical for extracting the mineral resources of the Moon and asteroids. His award-winning book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space inspired a generation of space exploration advocates. He died of leukemia in 1992.

Birth, education, and family life

O'Neill was born in Brooklyn, New York on February 6, 1927 to Edward Gerard O'Neill, a lawyer, and Dorothy Lewis O'Neill (née Kitchen).[4][5][6] He had no siblings. His family moved to Speculator, New York when his father temporarily retired for health reasons.[6] For high school, O'Neill attended Newburgh Free Academy in Newburgh, New York. While he was a student there he edited the school newspaper and took a job as a news broadcaster at a local radio station.[4] He graduated in 1944, during World War II, and enlisted in the United States Navy on his 17th birthday.[4][7] The Navy trained him as a radar technician, which sparked his interest in science.[4]After he was honorably discharged in 1946, O'Neill studied for an undergraduate degree in physics and mathematics at Swarthmore College.[7][8] As a child he had discussed the possibilities of humans in space with his parents, and in college he enjoyed working on rocket equations. However, he did not see space science as an option for a career path in physics, choosing instead to pursue high-energy physics.[9] In 1950 he graduated with Phi Beta Kappa honors. O'Neill performed his graduate studies at Cornell University with the help of an Atomic Energy Commission fellowship, and was awarded a Ph.D. in physics in 1954.[7]

O'Neill married Sylvia Turlington, also a Swarthmore graduate, in June 1950.[4][10] They had a son, Roger, and two daughters, Janet and Eleanor, before their marriage ended in divorce in 1966.[4][6]

One of O'Neill's favorite activities was flying. He held instrument certifications in both powered and sailplane flight and held the FAI Diamond Badge, a gliding award.[6][11] During his first cross-country glider flight in April 1973, he was assisted on the ground by Renate "Tasha" Steffen. He had met Tasha, who was 21 years younger than him, previously through the YMCA International Club. They were married the day after his flight.[5][6] They had a son, Edward O'Neill.[12]

High-energy physics research

After graduating from Cornell, O'Neill accepted a position as an instructor at Princeton University.[7] There he started his research into high-energy particle physics. In 1956, his second year of teaching, he published a two-page article that theorized that the particles produced by a particle accelerator could be stored for a few seconds in a storage ring.[1] The stored particles could then be directed to collide with another particle beam. This would increase the energy of the particle collision over the previous method, which directed the beam at a fixed target.[3] His ideas were not immediately accepted by the physics community.[4]O'Neill became an assistant professor at Princeton in 1956, and was promoted to associate professor in 1959.[4][5] He visited Stanford University in 1957 to meet with Professor Wolfgang K. H. Panofsky.[13] This resulted in a collaboration between Princeton and Stanford to build the Colliding Beam Experiment (CBX).[14] With a US$800,000 grant from the Office of Naval Research, construction on the first particle storage rings began in 1958 at the Stanford High-Energy Physics Laboratory.[15][16] He figured out how to capture the particles and, by pumping the air out to produce a vacuum, store them long enough to experiment on them.[17][18] CBX stored its first beam on March 28, 1962. O'Neill became a full professor of physics in 1965.[3]

In collaboration with Burton Richter, O'Neill performed the first colliding beam physics experiment in 1965. In this experiment, particle beams from the Stanford Linear Accelerator were collected in his storage rings and then directed to collide at an energy of 600 MeV. At the time, this was the highest energy involved in a particle collision. The results proved that the charge of an electron is contained in a volume less than 100 attometers across. O'Neill considered his device to be capable of only seconds of storage, but, by creating an even stronger vacuum, others were able to increase this to hours.[3] In 1979, he, with physicist David C. Cheng, wrote the graduate-level textbook Elementary Particle Physics: An Introduction.[5] He retired from teaching in 1985, but remained associated with Princeton as professor emeritus until his death.[3]

Space colonization

Origin of the idea (1969)

O'Neill saw great potential in the United States space program, especially the Apollo missions. He applied to the Astronaut Corps after NASA opened it up to civilian scientists in 1966. Later, when asked why he wanted to go on the Moon missions, he said, "to be alive now and not take part in it seemed terribly myopic".[6] He was put through NASA's rigorous mental and physical examinations. During this time he met Brian O'Leary, also a scientist-astronaut candidate, who became his good friend.[19] O'Leary was selected for Astronaut Group 6 but O'Neill was not.[20]

O'Neill became interested in the idea of space colonization in 1969 while he was teaching freshman physics at Princeton University.[3][21] His students were growing cynical about the benefits of science to humanity because of the controversy surrounding the Vietnam War.[22][23] To give them something relevant to study, he began using examples from the Apollo program as applications of elementary physics.[3][6] O'Neill posed the question during an extra seminar he gave to a few of his students: "Is the surface of a planet really the right place for an expanding technological civilization?"[21] His students' research convinced him that the answer was no.[21]

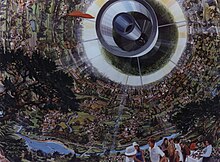

O'Neill was inspired by the papers written by his students. He began to work out the details of a program to build self-supporting space habitats in free space.[3][7] Among the details was how to provide the inhabitants of a space colony with an Earth-like environment. His students had designed giant pressurized structures, spun up to approximate Earth gravity by centrifugal force. With the population of the colony living on the inner surface of a sphere or cylinder, these structures resembled "inside-out planets". He found that pairing counter-rotating cylinders would eliminate the need to spin them using rockets.[21] This configuration has since been known as the O'Neill cylinder.

First paper (1970–1974)

Looking for an outlet for his ideas, O'Neill wrote a paper titled "The Colonization of Space", and for four years attempted to have it published.[24] He submitted it to several journals and magazines, including Scientific American and Science, only to have it rejected by the reviewers. During this timeO'Neill gave lectures on space colonization at Hampshire College, Princeton, and other schools. Many students and staff attending the lectures became enthusiastic about the possibility of living in space.[21] Another outlet for O'Neill to explore his ideas was with his children; on walks in the forest they speculated about life in a space colony.[25] His paper finally appeared in the September 1974 issue of Physics Today. In it, he argued that building space colonies would solve several important problems:

It is important to realize the enormous power of the space-colonization technique. If we begin to use it soon enough, and if we employ it wisely, at least five of the most serious problems now facing the world can be solved without recourse to repression: bringing every human being up to a living standard now enjoyed only by the most fortunate; protecting the biosphere from damage caused by transportation and industrial pollution; finding high quality living space for a world population that is doubling every 35 years; finding clean, practical energy sources; preventing overload of Earth's heat balance.

—Gerard K. O'Neill, "The Colonization of Space"[26]

He even explored the possibilities of flying gliders inside a space colony, finding that the enormous volume could support atmospheric thermals.[27] He calculated that humanity could expand on this man-made frontier to 20,000 times its population.[28] The initial colonies would be built at the Earth-Moon L4 and L5 Lagrange points.[29] L4 and L5 are stable points in the Solar System where a spacecraft can maintain its position without expending energy. The paper was well received, but many who would begin work on the project had already been introduced to his ideas before it was even published.[21] The paper received a few critical responses. Some questioned the practicality of lifting tens of thousands of people into orbit and his estimates for the production output of initial colonies.[30]

While he was waiting for his paper to be published, O'Neill organized a small two-day conference in May 1974 at Princeton to discuss the possibility of colonizing outer space.[21] The conference, titled First Conference on Space Colonization, was funded by Stewart Brand's Point Foundation and Princeton University.[31] Among those who attended were Eric Drexler (at the time a freshman at MIT), scientist-astronaut Joe Allen (from Astronaut Group 6), Freeman Dyson, and science reporter Walter Sullivan.[21] Representatives from NASA also attended and brought estimates of launch costs expected on the planned Space Shuttle.[21] O'Neill thought of the attendees as "a band of daring radicals".[32] Sullivan's article on the conference was published on the front page of The New York Times on May 13, 1974.[33] As media coverage grew, O'Neill was inundated with letters from people who were excited about living in space.[34] To stay in touch with them, O'Neill began keeping a mailing list and started sending out updates on his progress.[21][35] A few months later he heard Peter Glaser speak about solar power satellites at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. O'Neill realized that, by building these satellites, his space colonies could quickly recover the cost of their construction.[36] According to O'Neill, "the profound difference between this and everything else done in space is the potential of generating large amounts of new wealth".[6]

NASA studies (1975–1977)

O'Neill held a much larger conference the following May titled Princeton University Conference on Space Manufacturing.[37] At this conference more than two dozen speakers presented papers, including Keith and Carolyn Henson from Tucson, Arizona.[38][39]After the conference Carolyn Henson arranged a meeting between O'Neill and Arizona Congressman Morris Udall. Udall wrote a letter of support, which he asked the Hensons to publicize, for O'Neill's work.[38] The Hensons included his letter in the first issue of the L-5 Society newsletter, sent to everyone on O'Neill's mailing list and those who had signed up at the conference.[38][40]

In June 1975, O'Neill led a ten-week study of permanent space habitats at NASA Ames. During the study he was called away to testify on July 23 to the House Subcommittee on Space Science and Applications.[41] On January 19, 1976, he also appeared before the Senate Subcommittee on Aerospace Technology and National Needs. In a presentation titled Solar Power from Satellites, he laid out his case for an Apollo-style program for building power plants in space.[42] He returned to Ames in June 1976 and 1977 to lead studies on space manufacturing.[43] In these studies, NASA developed detailed plans to establish bases on the Moon where space-suited workers would mine the mineral resources needed to build space colonies and solar power satellites.[44]

Private funding (1977–1978)

Although NASA was supporting his work with grants of up to $500,000 per year, O'Neill became frustrated by the bureaucracy and politics inherent in government funded research.[4][23] He thought that small privately funded groups could develop space technology faster than government agencies.[3] In 1977, O'Neill and his wife Tasha founded the Space Studies Institute, a non-profit organization, at Princeton University.[7][45] SSI received initial funding of almost $100,000 from private donors, and in early 1978 began to support basic research into technologies needed for space manufacturing and settlement.[46]One of SSI's first grants funded the development of the mass driver, a device first proposed by O'Neill in 1974.[47][48] Mass drivers are based on the coilgun design, adapted to accelerate a non-magnetic object.[49] One application O'Neill proposed for mass drivers was to throw baseball-sized chunks of ore mined from the surface of the Moon into space.[50][51] Once in space, the ore could be used as raw material for building space colonies and solar power satellites. He took a sabbatical from Princeton to work on mass drivers at MIT. There he served as the Hunsaker Visiting Professor of Aerospace during the 1976–77 academic year.[52] At MIT, he, Henry H. Kolm, and a group of student volunteers built their first mass driver prototype.[32][43][47] The eight-foot (2.5 m) long prototype could apply 33 g (320 m/s2) of acceleration to an object inserted into it.[32][43][50] With financial assistance from SSI, later prototypes improved this to 1,800 g (18,000 m/s2), enough acceleration that a mass driver only 520 feet (160 m) long could launch material off the surface of the Moon.[43]

Opposition (1977–1985)

In 1977, O'Neill saw the peak of interest in space colonization, along with the publication of his first book, The High Frontier.[38] He and his wife were flying between meetings, interviews, and hearings.[6] On October 9, the CBS program 60 Minutes ran a segment about space colonies. Later they aired responses from the viewers, which included one from Senator William Proxmire, chairman of the Senate Subcommittee responsible for NASA's budget. His response was, "it's the best argument yet for chopping NASA's funding to the bone .... I say not a penny for this nutty fantasy".[53] He successfully eliminated spending on space colonization research from the budget.[54] In 1978, Paul Werbos wrote for the L-5 newsletter, "no one expects Congress to commit us to O'Neill's concept of large-scale space habitats; people in NASA are almost paranoid about the public relations aspects of the idea".[55] When it became clear that a government funded colonization effort was politically impossible, popular support for O'Neill's ideas started to evaporate.[38]Other pressures on O'Neill's colonization plan were the high cost of access to Earth orbit and the declining cost of energy. Building solar power stations in space was economically attractive when energy prices spiked during the 1979 oil crisis. When prices dropped in the early 1980s, funding for space solar power research dried up.[56] His plan had also been based on NASA's estimates for the flight rate and launch cost of the Space Shuttle, numbers that turned out to have been wildly optimistic. His 1977 book quoted a Space Shuttle launch cost of $10 million, but in 1981 the subsidized price given to commercial customers started at $38 million.[57][58] Eventual accounting of the full cost of a launch in 1985 raised this as high as $180 million per flight.[59]

O'Neill was appointed by United States President Ronald Reagan to the National Commission on Space in 1985.[7] The commission, led by former NASA administrator Thomas Paine, proposed that the government commit to opening the inner Solar System for human settlement within 50 years.[60] Their report was released in May 1986, four months after the Space Shuttle Challenger broke up on ascent.[60]

Writing career

O'Neill's popular science book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space (1977) combined fictional accounts of space settlers with an explanation of his plan to build space colonies. Its publication established him as the spokesman for the space colonization movement.[3] It won the Phi Beta Kappa Award in Science that year, and prompted Swarthmore College to grant him an honorary doctorate.[5][61] The High Frontier has been translated into five languages and remained in print as of 2008.[43]

His 1981 book 2081: A Hopeful View of the Human Future was an exercise in futurology. O'Neill narrated it as a visitor to Earth from a space colony beyond Pluto.[62] The book explored the effects of technologies he called "drivers of change" on the coming century. Some technologies he described were space colonies, solar power satellites, anti-aging drugs, hydrogen-propelled cars, climate control, and underground magnetic trains. He left the social structure of the 1980s intact, assuming that humanity would remain unchanged even as it expanded into the Solar System. Reviews of 2081 were mixed. New York Times reviewer John Noble Wilford found the book "imagination-stirring", but Charles Nicol thought the technologies described were unacceptably far-fetched.[5]

In his book The Technology Edge, published in 1983, O'Neill wrote about economic competition with Japan.[63] He argued that the United States had to develop six industries to compete: microengineering, robotics, genetic engineering, magnetic flight, family aircraft, and space science.[51] He also thought that industrial development was suffering from short-sighted executives, self-interested unions, high taxes, and poor education of Americans. According to reviewer Henry Weil, O'Neill's detailed explanations of emerging technologies differentiated the book from others on the subject.[63]

Entrepreneurial efforts

O'Neill founded Geostar Corporation to develop a satellite position determination system for which he was granted a patent in 1982.[64] The system, primarily intended to track aircraft, was called Radio Determination Satellite Service (RDSS).[51] In April 1983 Geostar applied to the FCC for a license to broadcast from three satellites, which would cover the entire United States. Geostar launched GSTAR-2 into geosynchronous orbit in 1986. Its transmitter package permanently failed two months later, so Geostar began tests of RDSS by transmitting from other satellites.[65] With his health failing, O'Neill became less involved with the company at the same time it started to run into trouble.[66] In February 1991 Geostar filed for bankruptcy and its licenses were sold to Motorola for the Iridium satellite constellation project.[67] Although the system was eventually replaced by GPS, O'Neill made significant advances in the field of position determination.[66]

O'Neill founded O'Neill Communications in Princeton in 1986. He introduced his Local Area Wireless Networking, or LAWN, system at the PC Expo in New York in 1989.[68] The LAWN system allowed two computers to exchange messages over a range of a couple hundred feet at a cost of about $500 per node.[69] O'Neill Communications went out of business in 1993; the LAWN technology was sold to Omnispread Communications. As of 2008, Omnispread continued to sell a variant of O'Neill's LAWN system.[70]

On November 18, 1991, O'Neill filed a patent application for a high-speed train system. He called the company he wanted to form VSE International, for velocity, silence, and efficiency.[3] However, the concept itself he called Magnetic Flight. The vehicles, instead of running on a pair of tracks, would be elevated using electromagnetic force by a single track within a tube (permanent magnets in the track, with variable magnets on the vehicle), and propelled by electromagnetic forces through tunnels. He estimated the trains could reach speeds of up to 2,500 mph (4,000 km/h) — about five times faster than a jet airliner — if the air was evacuated from the tunnels.[7] To obtain such speeds, the vehicle would accelerate for the first half of the trip, and then decelerate for the second half of the trip. The acceleration was planned to be a maximum of about one-half of the force of gravity. O'Neill planned to build a network of stations connected by these tunnels, but he died two years before his first patent on it was granted.[3]

Death and legacy

O'Neill was diagnosed with leukemia in 1985.[66] He died on April 27, 1992, from complications of the disease at the Sequoia Hospital in Redwood City, California.[7][8] He was survived by his wife Tasha, his ex-wife Sylvia, and his four children.[7][71] A sample of his incinerated remains was buried in space.[72] The vial containing his ashes was attached to a Pegasus XL rocket and launched into Earth orbit on April 21, 1997.[72][73] It re-entered the atmosphere in May 2002.[74]

O'Neill directed his Space Studies Institute to continue their efforts "until people are living and working in space".[75] After his death, management of SSI was passed to his son Roger and colleague Freeman Dyson.[43] SSI continued to hold conferences every other year to bring together scientists studying space colonization until 2001.[76]

Henry Kolm went on to start Magplane Technology in the 1990s to develop the magnetic transportation technology that O'Neill had written about. In 2007, Magplane demonstrated a working magnetic pipeline system to transport phosphate ore in Florida. The system ran at a speed of 40 mph (65 km/h), far slower than the high-speed trains O'Neill envisioned.[77][78]

All three of the founders of the Space Frontier Foundation, an organization dedicated to opening the space frontier to human settlement, were supporters of O'Neill's ideas and had worked with him in various capacities at the Space Studies Institute.[79] One of them, Rick Tumlinson, describes three men as models for space advocacy: Wernher von Braun, Gerard K. O'Neill, and Carl Sagan. Von Braun pushed for "projects that ordinary people can be proud of but not participate in".[80] Sagan wanted to explore the universe from a distance. O'Neill, with his grand scheme for settlement of the Solar System, emphasized moving ordinary people off the Earth "en masse".[80]

The National Space Society (NSS) gives the Gerard K. O'Neill Memorial Award for Space Settlement Advocacy to individuals noted for their contributions in the area of space settlement. Their contributions can be scientific, legislative, and educational. The award is a trophy cast in the shape of a Bernal sphere. The NSS first bestowed the award in 2007 on lunar entrepreneur and former astronaut Harrison Schmitt. In 2008, it was given to physicist John Marburger.[81]

In fiction, the protagonist of Stephen Baxter's Manifold:Time names his spaceship the Gerard K. O'Neill.

As of November, 2013, Gerard O'Neill's papers and work are now located in the archives at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.

Publications

Books

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (1977). The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space. New York: William Morrow & Company. ISBN 0-9622379-0-6.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (ed.); O'Leary, Brian (1977). Space-Based Manufacturing from Nonterrestrial Materials. New York: American Institute of Aeronautics. ISBN 0-915928-21-3.

- Cheng, David C.; O'Neill, Gerard K. (1979). Elementary Particle Physics: An Introduction. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-05463-9.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (1981). 2081: A Hopeful View of the Human Future. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-44751-3.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (1983). The Technology Edge: Opportunities for America in world competition. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-44766-1.

Papers

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (1954). "Time-of-Flight Measurements on the Inelastic Scattering of 14.8-Mev Neutrons". Physical Review 95 (5): 1235–1245. Bibcode:1954PhRv...95.1235O. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.95.1235.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (April 1956). "Storage-Ring Synchrotron: Device for High-Energy Physics Research". Physical Review 102 (5): 1418. Bibcode:1956PhRv..102.1418O. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.102.1418.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (August 1963). "Storage Rings". Science 141 (3582): 679–686. Bibcode:1963Sci...141..679O. doi:10.1126/science.141.3582.679. PMID 17752920.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (May 1968). "A High-Resolution Orbiting Telescope: New techniques would lead to orbiting an optical telescope 25 times the diameter of Palomar's". Science 160 (3830): 843–847. Bibcode:1968Sci...160..843O. doi:10.1126/science.160.3830.843. PMID 17774392.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (September 1974). "The Colonization of Space". Physics Today 27 (9): 32–40. Bibcode:1974PhT....27i..32O. doi:10.1063/1.3128863.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (Fall 1975). "The High Frontier". CoEvolution Quarterly (7): 6–9. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (December 5, 1975). "Space Colonies and Energy Supply to the Earth". Science 190 (4218): 943–947. Bibcode:1975Sci...190..943O. doi:10.1126/science.190.4218.943.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (October 1976). "Engineering a Space Manufacturing Center". Astronautics and Aeronautics 14: 20–28, 36. Bibcode:1976AsAer..14...20P.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (March 1978). "The Low (Profile) Road to Space Manufacturing". Astronautics and Aeronautics 16 (3): 18–32. Bibcode:1978AsAer..16...18G.

- O'Neill, Gerard K.; Driggers, Gerald; O'Leary, Brian (October 1980). "New Routes to Manufacturing in Space". Astronautics and Aeronautics 18 (10): 46–51. Bibcode:1980AsAer..18...46G.

- O'Neill, Gerard K.; Kolm, Henry H. (November 1980). "High acceleration mass drivers". Acta Astronautica 7 (11): 1229–1238. Bibcode:1980AcAau...7.1229O. doi:10.1016/0094-5765(80)90002-8.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (1981). "Where is everybody? Some new answers". Nature 294 (25): 25. Bibcode:1981Natur.294...25O. doi:10.1038/294025a0.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (March 1981). "Satellite Air Traffic Control". Astronautics and Aeronautics 19 (3): 27–31.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (1981). "Recent developments in mass drivers". Space manufacturing 4: 97–104. OCLC 8112602.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (July 1982). "Satellites Instead". AOPA Pilot 25 (1): 51–54, 59–63.

- O'Neill, Gerard K. (September 1983). "Geostar". AOPA Pilot 26 (9): 53–57.

- O'Neill, Gerard K.; Maryniak, G. E. (1988). "Radiation Shielding to Solar Power Satellites: Results of the January 1988 SSI/Princeton Lunar Systems Study". Lunar Bases 2: 185. Bibcode:1988LPICo.652..185O.

Patents

O'Neill was granted six patents in total (two posthumously) in the areas of global position determination and magnetic levitation.- US 4359733 Satellite-based vehicle position determining system, granted November 16, 1982

- US 4744083 Satellite-based position determining and message transfer system with monitoring of link quality, granted May 10, 1988

- US 4839656 Position determination and message transfer system employing satellites and stored terrain map, granted June 13, 1989

- US 4965586 Position determination and message transfer system employing satellites and stored terrain map, granted October 23, 1990

- US 5282424 High speed transport system, granted February 1, 1994

- US 5433155 High speed transport system, granted July 18, 1995

of an atmospheric

of an atmospheric  (in kg) of X in the box to its removal rate, which is the sum of the flow of X out of the box (

(in kg) of X in the box to its removal rate, which is the sum of the flow of X out of the box ( ), chemical loss of X (

), chemical loss of X ( ), and

), and  ) (all in kg/s):

) (all in kg/s):  .

.