From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In particle physics, the electroweak interaction is the unified description of two of the four known fundamental interactions of nature: electromagnetism and the weak interaction. Although these two forces appear very different at everyday low energies, the theory models them as two different aspects of the same force. Above the unification energy, on the order of 100 GeV, they would merge into a single electroweak force. Thus, if the universe is hot enough (approximately 1015 K, a temperature exceeded until shortly after the Big Bang), then the electromagnetic force and weak force merge into a combined electroweak force. During the electroweak epoch, the electroweak force separated from the strong force. During the quark epoch, the electroweak force split into the electromagnetic and weak force.

For contributions to the unification of the weak and electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles, Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam, and Steven Weinberg were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1979.[1][2] The existence of the electroweak interactions was experimentally established in two stages, the first being the discovery of neutral currents in neutrino scattering by the Gargamelle collaboration in 1973, and the second in 1983 by the UA1 and the UA2 collaborations that involved the discovery of the W and Z gauge bosons in proton–antiproton collisions at the converted Super Proton Synchrotron. In 1999, Gerardus 't Hooft and Martinus Veltman were awarded the Nobel prize for showing that the electroweak theory is renormalizable.

Mathematically, the unification is accomplished under an SU(2) × U(1) gauge group. The corresponding gauge bosons are the three W bosons of weak isospin from SU(2) (W+, W0, and W−), and the B0 boson of weak hypercharge from U(1), respectively, all of which are massless.

In the Standard Model, the W± and Z0 bosons, and the photon, are produced by the spontaneous symmetry breaking of the electroweak symmetry from SU(2) × U(1)Y to U(1)em, caused by the Higgs mechanism (see also Higgs boson).[3][4][5][6] U(1)Y and U(1)em are different copies of U(1); the generator of U(1)em is given by Q = Y/2 + I3, where Y is the generator of U(1)Y (called the weak hypercharge), and I3 is one of the SU(2) generators (a component of weak isospin).

The spontaneous symmetry breaking causes the W0 and B0 bosons to coalesce together into two different bosons – the Z0 boson, and the photon (γ) as follows:

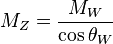

Where θW is the weak mixing angle. The axes representing the particles have essentially just been rotated, in the (W0, B0) plane, by the angle θW. This also introduces a discrepancy between the mass of the Z0 and the mass of the W± particles (denoted as MZ and MW, respectively);

term describes the interaction between the three W particles and the B particle.

term describes the interaction between the three W particles and the B particle.

(

( ) and

) and  are the field strength tensors for the weak isospin and weak hypercharge fields.

are the field strength tensors for the weak isospin and weak hypercharge fields.

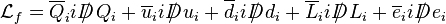

is the kinetic term for the Standard Model fermions. The interaction of the gauge bosons and the fermions are through the gauge covariant derivative.

is the kinetic term for the Standard Model fermions. The interaction of the gauge bosons and the fermions are through the gauge covariant derivative.

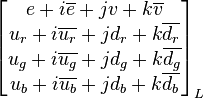

runs over the three generations of fermions,

runs over the three generations of fermions,  ,

,  , and

, and  are the left-handed doublet, right-handed singlet up, and right handed singlet down quark fields, and

are the left-handed doublet, right-handed singlet up, and right handed singlet down quark fields, and  and

and  are the left-handed doublet and right-handed singlet electron fields.

are the left-handed doublet and right-handed singlet electron fields.

The h term describes the Higgs field F.

contains all the quadratic terms of the Lagrangian, which include the dynamic terms (the partial derivatives) and the mass terms (conspicuously absent from the Lagrangian before symmetry breaking)

contains all the quadratic terms of the Lagrangian, which include the dynamic terms (the partial derivatives) and the mass terms (conspicuously absent from the Lagrangian before symmetry breaking)

,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are given as

are given as

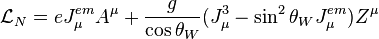

and charged current

and charged current  components of the Lagrangian contain the interactions between the fermions and gauge bosons.

components of the Lagrangian contain the interactions between the fermions and gauge bosons.

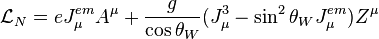

and the neutral weak current

and the neutral weak current  are

are

and

and  are the fermions' electric charges and weak isospin.

are the fermions' electric charges and weak isospin.

The charged current part of the Lagrangian is given by

contains the Higgs three-point and four-point self interaction terms.

contains the Higgs three-point and four-point self interaction terms.

contains the Higgs interactions with gauge vector bosons.

contains the Higgs interactions with gauge vector bosons.

contains the gauge three-point self interactions.

contains the gauge three-point self interactions.

contains the gauge four-point self interactions

contains the gauge four-point self interactions

contains the Yukawa interactions between the fermions and the Higgs field.

contains the Yukawa interactions between the fermions and the Higgs field.

factors in the weak couplings: these factors project out the left handed components of the spinor fields. This is why electroweak theory (after symmetry breaking) is commonly said to be a chiral theory.

factors in the weak couplings: these factors project out the left handed components of the spinor fields. This is why electroweak theory (after symmetry breaking) is commonly said to be a chiral theory.

For contributions to the unification of the weak and electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles, Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam, and Steven Weinberg were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1979.[1][2] The existence of the electroweak interactions was experimentally established in two stages, the first being the discovery of neutral currents in neutrino scattering by the Gargamelle collaboration in 1973, and the second in 1983 by the UA1 and the UA2 collaborations that involved the discovery of the W and Z gauge bosons in proton–antiproton collisions at the converted Super Proton Synchrotron. In 1999, Gerardus 't Hooft and Martinus Veltman were awarded the Nobel prize for showing that the electroweak theory is renormalizable.

Formulation

The pattern of weak isospin, T3, and weak hypercharge, YW, of the known elementary particles, showing electric charge, Q, along the weak mixing angle. The neutral Higgs field (circled) breaks the electroweak symmetry and interacts with other particles to give them mass. Three components of the Higgs field become part of the massive W and Z bosons.

Mathematically, the unification is accomplished under an SU(2) × U(1) gauge group. The corresponding gauge bosons are the three W bosons of weak isospin from SU(2) (W+, W0, and W−), and the B0 boson of weak hypercharge from U(1), respectively, all of which are massless.

In the Standard Model, the W± and Z0 bosons, and the photon, are produced by the spontaneous symmetry breaking of the electroweak symmetry from SU(2) × U(1)Y to U(1)em, caused by the Higgs mechanism (see also Higgs boson).[3][4][5][6] U(1)Y and U(1)em are different copies of U(1); the generator of U(1)em is given by Q = Y/2 + I3, where Y is the generator of U(1)Y (called the weak hypercharge), and I3 is one of the SU(2) generators (a component of weak isospin).

The spontaneous symmetry breaking causes the W0 and B0 bosons to coalesce together into two different bosons – the Z0 boson, and the photon (γ) as follows:

Where θW is the weak mixing angle. The axes representing the particles have essentially just been rotated, in the (W0, B0) plane, by the angle θW. This also introduces a discrepancy between the mass of the Z0 and the mass of the W± particles (denoted as MZ and MW, respectively);

Lagrangian

Before electroweak symmetry breaking

The Lagrangian for the electroweak interactions is divided into four parts before electroweak symmetry breaking term describes the interaction between the three W particles and the B particle.

term describes the interaction between the three W particles and the B particle. ,

,

(

( ) and

) and  are the field strength tensors for the weak isospin and weak hypercharge fields.

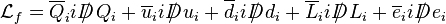

are the field strength tensors for the weak isospin and weak hypercharge fields. is the kinetic term for the Standard Model fermions. The interaction of the gauge bosons and the fermions are through the gauge covariant derivative.

is the kinetic term for the Standard Model fermions. The interaction of the gauge bosons and the fermions are through the gauge covariant derivative. ,

,

runs over the three generations of fermions,

runs over the three generations of fermions,  ,

,  , and

, and  are the left-handed doublet, right-handed singlet up, and right handed singlet down quark fields, and

are the left-handed doublet, right-handed singlet up, and right handed singlet down quark fields, and  and

and  are the left-handed doublet and right-handed singlet electron fields.

are the left-handed doublet and right-handed singlet electron fields.The h term describes the Higgs field F.

After electroweak symmetry breaking

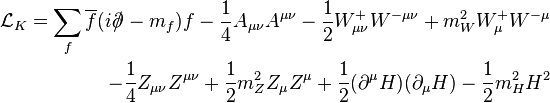

The Lagrangian reorganizes itself after the Higgs boson acquires a vacuum expectation value. Due to its complexity, this Lagrangian is best described by breaking it up into several parts as follows. contains all the quadratic terms of the Lagrangian, which include the dynamic terms (the partial derivatives) and the mass terms (conspicuously absent from the Lagrangian before symmetry breaking)

contains all the quadratic terms of the Lagrangian, which include the dynamic terms (the partial derivatives) and the mass terms (conspicuously absent from the Lagrangian before symmetry breaking) ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are given as

are given as , (replace X by the relevant field, and fabc with the structure constants for the gauge group).

, (replace X by the relevant field, and fabc with the structure constants for the gauge group).

and charged current

and charged current  components of the Lagrangian contain the interactions between the fermions and gauge bosons.

components of the Lagrangian contain the interactions between the fermions and gauge bosons. ,

,

and the neutral weak current

and the neutral weak current  are

are ,

,

and

and  are the fermions' electric charges and weak isospin.

are the fermions' electric charges and weak isospin.The charged current part of the Lagrangian is given by

contains the Higgs three-point and four-point self interaction terms.

contains the Higgs three-point and four-point self interaction terms. contains the Higgs interactions with gauge vector bosons.

contains the Higgs interactions with gauge vector bosons. contains the gauge three-point self interactions.

contains the gauge three-point self interactions. contains the gauge four-point self interactions

contains the gauge four-point self interactions contains the Yukawa interactions between the fermions and the Higgs field.

contains the Yukawa interactions between the fermions and the Higgs field. factors in the weak couplings: these factors project out the left handed components of the spinor fields. This is why electroweak theory (after symmetry breaking) is commonly said to be a chiral theory.

factors in the weak couplings: these factors project out the left handed components of the spinor fields. This is why electroweak theory (after symmetry breaking) is commonly said to be a chiral theory.

,

, ,

,

, (replace X by the relevant field, and fabc with the structure constants for the gauge group).

, (replace X by the relevant field, and fabc with the structure constants for the gauge group). ,

, ,

,

![\mathcal{L}_C=-\frac g{\sqrt2}\left[\overline u_i\gamma^\mu\frac{1-\gamma^5}2M^{CKM}_{ij}d_j+\overline\nu_i\gamma^\mu\frac{1-\gamma^5}2e_i\right]W_\mu^++h.c.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/7/e/5/7e50221ac5f6c3c7de5c6ef69f07c056.png)

![\mathcal{L}_{WWV}=-ig[(W_{\mu\nu}^+W^{-\mu}-W^{+\mu}W_{\mu\nu}^-)(A^\nu\sin\theta_W-Z^\nu\cos\theta_W)+W_\nu^-W_\mu^+(A^{\mu\nu}\sin\theta_W-Z^{\mu\nu}\cos\theta_W)]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/1/7/e/17e507ca8a9a9c019d3b9f5ccc8ec1a8.png)

![\begin{align}

\mathcal{L}_{WWVV} = -\frac{g^2}4 \Big\{&[2W_\mu^+W^{-\mu} + (A_\mu\sin\theta_W - Z_\mu\cos\theta_W)^2]^2

\\

&- [W_\mu^+W_\nu^- + W_\nu^+W_\mu^- + (A_\mu\sin\theta_W - Z_\mu\cos\theta_W) (A_\nu\sin\theta_W - Z_\nu\cos\theta_W)]^2\Big\}

\end{align}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/b/f/c/bfc808b78f8a2ba69a0e789a7db3ad72.png)

.

.

.

.

is a quaternion valued spinor,

is a quaternion valued spinor,  is quaternion hermitian

is quaternion hermitian  is a pure imaginary quaternion (both of which are 4-vector bosons) then the interaction term is:

is a pure imaginary quaternion (both of which are 4-vector bosons) then the interaction term is:

![[\psi_A,\psi_B] \subset J_3(O)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/a/f/2/af209963d8261f898194b8189325cf7f.png)

.

.

in

in

in flipped

in flipped

and the anti-triplet Higgs

and the anti-triplet Higgs  in

in