From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Four Corners Monument is where the states of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah meet. (The states are listed in clockwise order.)

The Colorado Plateau, also known as the Colorado Plateau Province, is a physiographic region of the Intermontane Plateaus, roughly centered on the Four Corners region of the southwestern United States. The province covers an area of 337,000 km2 (130,000 mi2) within western Colorado, northwestern New Mexico, southern and eastern Utah, and northern Arizona. About 90% of the area is drained by the Colorado River and its main tributaries: the Green, San Juan, and Little Colorado.[1][2]

The Colorado Plateau is largely made up of high desert, with scattered areas of forests. In the southwest corner of the Colorado Plateau lies the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River. Much of the Plateau's landscape is related, in both appearance and geologic history, to the Grand Canyon. The nickname "Red Rock Country" suggests the brightly colored rock left bare to the view by dryness and erosion. Domes, hoodoos, fins, reefs, goblins, river narrows, natural bridges, and slot canyons are only some of the additional features typical of the Plateau.

The Colorado Plateau has the greatest concentration of U.S. National Park Service (NPS) units in the country. Among its ten National Parks are Grand Canyon, Zion, Bryce Canyon, Capitol Reef, Canyonlands, Arches, Mesa Verde, and Petrified Forest. Among its 17 National Monuments are Dinosaur, Hovenweep, Wupatki, Sunset Crater Volcano, Grand Staircase-Escalante, Natural Bridges, Canyons of the Ancients, Chaco Culture National Historical Park and the Colorado National Monument.

Geography

The Green River runs north to south from Wyoming, briefly through Colorado, and converges with the Colorado River in southeastern Utah.

The province is bounded by the Rocky Mountains in Colorado, and by the Uinta Mountains and Wasatch Mountains branches of the Rockies in northern and central Utah. It is also bounded by the Rio Grande Rift, Mogollon Rim and the Basin and Range Province. Isolated ranges of the Southern Rocky Mountains such as the San Juan Mountains in Colorado and the La Sal Mountains in Utah intermix into the central and southern parts of the Colorado Plateau. It is composed of seven sections:[3]

- Uinta Basin Section

- High Plateaus Section

- Grand Canyon Section

- Canyon Lands Section

- Navajo Section

- Datil-Mogollon Section[4]

- Acoma-Zuni Section[4]

Occupying the southeast corner of the Colorado Plateau is the Datil Section. Thick sequences of mid-Tertiary to late-Cenozoic-aged lava covers this section.

Development of the province has in large part been influenced by structural features in its oldest rocks. Part of the Wasatch Line and its various faults form the western edge of the province. Faults that run parallel to the Wasatch Fault that lies along the Wasatch Range form the boundaries between the plateaus in the High Plateaus Section.[6] The Uinta Basin, Uncompahgre Uplift, and the Paradox Basin were also created by movement along structural weaknesses in the region's oldest rock.

In Utah, the province includes several higher fault-separated plateaus:

- Awapa Plateau

- Aquarius Plateau

- Kaiparowits Plateau

- Markagunt Plateau

- Paunsaugunt Plateau

- Sevier Plateau

- Fishlake Plateau

- Pavant Plateau

- Gunnison Plateau and the

- Tavaputs Plateau.

Within these rocks are abundant mineral resources that include uranium, coal, petroleum, and natural gas. Study of the area's unusually clear geologic history (which is laid bare due to the arid and semiarid conditions) has greatly advanced that science.

A rain shadow from the Sierra Nevada far to the west and the many ranges of the Basin and Range means that the Colorado Plateau receives 15 to 40 cm (6 to 16 in.) of annual precipitation.[8] Higher areas receive more precipitation and are covered in forests of pine, fir, and spruce.

Though it can be said that the Plateau roughly centers on the Four Corners, Black Mesa in northern Arizona is much closer to the east-west, north-south midpoint of the Plateau Province. Lying southeast of Glen Canyon and southwest of Monument Valley at the north end of the Hopi Reservation, this remote coal-laden highland has about half of the Colorado Plateau's acreage north of it, half south of it, half west of it, and half east of it.

History

The Ancestral Puebloan People lived in the region from around 2000 to 700 years ago.[9]A party from Santa Fe led by Fathers Dominguez and Escalante, unsuccessfully seeking an overland route to California, made a five-month out-and-back trip through much of the Plateau in 1776-1777.[10]

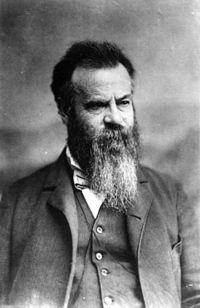

Despite having lost one arm in the American Civil War, U.S. Army Major and geologist John Wesley Powell explored the area in 1869 and 1872. Using fragile boats and small groups of men the Powell Geographic Expedition charted this largely unknown region of the United States for the federal government.

Construction of the Hoover Dam in the 1930s and the Glen Canyon Dam in the 1960s changed the character of the Colorado River. Dramatically reduced sediment load changed its color from reddish brown (Colorado is Spanish for "colored") to mostly clear. The apparent green color is from algae on the riverbed's rocks, not from any significant amount of suspended material. The lack of sediment has also starved sand bars and beaches but an experimental 12 day long controlled flood from Glen Canyon Dam in 1996 showed substantial restoration. Similar floods are planned for every 5 to 10 years.[11]

Geology

The Permian through Jurassic stratigraphy of the Colorado Plateau area of southeastern Utah that makes up much of the famous prominent rock formations in protected areas such as Capitol Reef National Park and Canyonlands National Park. From top to bottom: Rounded tan domes of the Navajo Sandstone, layered red Kayenta Formation, cliff-forming, vertically jointed, red Wingate Sandstone, slope-forming, purplish Chinle Formation, layered, lighter-red Moenkopi Formation, and white, layered Cutler Formation sandstone. Picture from Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

MODIS satellite image of Grand Canyon, Lake Powell (black, left of center) and the Colorado Plateau. White areas are snow-capped.

One of the most geologically intriguing features of the Colorado Plateau is its remarkable stability. Relatively little rock deformation such as faulting and folding has affected this high, thick crustal block within the last 600 million years or so. In contrast, provinces that have suffered severe deformation surround the plateau. Mountain building thrust up the Rocky Mountains to the north and east and tremendous, earth-stretching tension created the Basin and Range province to the west and south. Sub ranges of the Southern Rocky Mountains are scattered throughout the Colorado Plateau.

The Precambrian and Paleozoic history of the Colorado Plateau is best revealed near its southern end where the Grand Canyon has exposed rocks with ages that span almost 2 billion years. The oldest rocks at river level are igneous and metamorphic and have been lumped together as "Vishnu Basement Rocks"; the oldest ages recorded by these rocks fall in the range 1950 to 1680 million years. An erosion surface on the "Vishnu Basement Rocks" is covered by sedimentary rocks and basalt flows, and these rocks formed in the interval from about 1250 to 750 million years ago: in turn, they were uplifted and split into a range of fault-block mountains.[12] Erosion greatly reduced this mountain range prior to the encroachment of a seaway along the passive western edge of the continent in the early Paleozoic. At the canyon rim is the Kaibab Formation, limestone deposited in the late Paleozoic (Permian) about 270 million years ago.

A 12,000 to 15,000 ft. (3700 to 4600 m) high extension of the Ancestral Rocky Mountains called the Uncompahgre Mountains were uplifted and the adjacent Paradox Basin subsided. Almost 4 mi. (6.4 km) of sediment from the mountains and evaporites from the sea were deposited (see geology of the Canyonlands area for detail).[13] Most of the formations were deposited in warm shallow seas and near-shore environments (such as beaches and swamps) as the seashore repeatedly advanced and retreated over the edge of a proto-North America (for detail, see geology of the Grand Canyon area). The province was probably on a continental margin throughout the late Precambrian and most of the Paleozoic era. Igneous rocks injected millions of years later form a marbled network through parts of the Colorado Plateau's darker metamorphic basement. By 600 million years ago North America had been leveled off to a remarkably smooth surface.

Throughout the Paleozoic Era, tropical seas periodically inundated the Colorado Plateau region. Thick layers of limestone, sandstone, siltstone, and shale were laid down in the shallow marine waters. During times when the seas retreated, stream deposits and dune sands were deposited or older layers were removed by erosion. Over 300 million years passed as layer upon layer of sediment accumulated.

It was not until the upheavals that coincided with the formation of the supercontinent Pangea began about 250 million years ago that deposits of marine sediment waned and terrestrial deposits dominate. In late Paleozoic and much of the Mesozoic era the region was affected by a series of orogenies (mountain-building events) that deformed western North America and caused a great deal of uplift. Eruptions from volcanic mountain ranges to the west buried vast regions beneath ashy debris. Short-lived rivers, lakes, and inland seas left sedimentary records of their passage. Streams, ponds and lakes created formations such as the Chinle, Moenave, and Kayenta in the Mesozoic era. Later a vast desert formed the Navajo and Temple Cap formations and dry near-shore environment formed the Carmel (see geology of the Zion and Kolob canyons area for details).

The area was again covered by a warm shallow sea when the Cretaceous Seaway opened in late Mesozoic time. The Dakota Sandstone and the Tropic Shale were deposited in the warm shallow waters of this advancing and retreating seaway. Several other formations were also created but were mostly eroded following two major periods of uplift.

The Laramide orogeny closed the seaway and uplifted a large belt of crust from Montana to Mexico, with the Colorado Plateau region being the largest block. Thrust faults in Colorado are thought to have formed from a slight clockwise movement of the region, which acted as a rigid crustal block. The Colorado Plateau Province was uplifted largely as a single block, possibly due to its relative thickness. This relative thickness may be why compressional forces from the orogeny were mostly transmitted through the province instead of deforming it.[6] Pre-existing weaknesses in Precambrian rocks were exploited and reactivated by the compression. It was along these ancient faults and other deeply buried structures that much of the province's relatively small and gently inclined flexures (such as anticlines, synclines, and monoclines) formed.[6] Some of the prominent isolated mountain ranges of the Plateau, such as Ute Mountain and the Carrizo Mountains, both near the Four Corners, are cored by igneous rocks that were emplaced about 70 million years ago.

Minor uplift events continued through the start of the Cenozoic era and were accompanied by some basaltic lava eruptions and mild deformation. The colorful Claron Formation that forms the delicate hoodoos of Bryce Amphitheater and Cedar Breaks was then laid down as sediments in cool streams and lakes (see geology of the Bryce Canyon area for details). The flat-lying Chuska Sandstone was deposited about 34 million years ago; the sandstone is predominantly of eolian origin and locally more than 500 meters thick. The Chuska Sandstone caps the Chuska mountains, and it lies unconformably on Mesozoic rocks deformed during the Laramide orogeny.

Younger igneous rocks form spectacular topographic features. The Henry Mountains, La Sal Range, and Abajo Mountains, ranges that dominate many views in southeastern Utah, are formed about igneous rocks that were intruded in the interval from 20 to 31 million years: some igneous intrusions in these mountains form laccoliths, a form of intrusion recognized by Grove Karl Gilbert during his studies of the Henry Mountains. Ship Rock (also called Shiprock), in northwestern New Mexico, and Church Rock and Agathla, near Monument Valley, are erosional remnants of potassium-rich igneous rocks and associated breccias of the Navajo Volcanic Field, produced about 25 million years ago. The Hopi Buttes in northeastern Arizona are held up by resistant sheets of sodic volcanic rocks, extruded about 7 million years ago. More recent igneous rocks are concentrated nearer the margins of the Colorado Plateau. The San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff, south of the Grand Canyon, are volcanic landforms produced by igneous activity that began in that area about 6 million years ago and continued until 1064 C.E., when basalt erupted in Sunset Crater National Monument. Mount Taylor, near Grants, New Mexico, is a volcanic structure with a history similar to that of the San Francisco Peaks: a basalt flow closer to Grants was extruded only about 3000 years ago (see El Malpais National Monument). These young igneous rocks may record processes in the Earth's mantle that are eating away at deep margins of the relatively stable block of the Plateau.

Tectonic activity resumed in Mid Cenozoic time and started to unevenly uplift and slightly tilt the Colorado Plateau region and the region to the west some 20 million years ago (as much as 3 kilometers of uplift occurred). Streams had their gradient increased and they responded by downcutting faster. Headward erosion and mass wasting helped to erode cliffs back into their fault-bounded plateaus, widening the basins in-between. Some plateaus have been so severely reduced in size this way that they become mesas or even buttes. Monoclines form as a result of uplift bending the rock units. Eroded monoclines leave steeply tilted resistant rock called a hogback and the less steep version is a cuesta.

Great tension developed in the crust, probably related to changing plate motions far to the west. As the crust stretched, the Basin and Range province broke up into a multitude of down-dropped valleys and elongate mountains. Major faults, such as the Hurricane Fault, developed that separate the two regions. The dry climate was in large part a rainshadow effect resulting from the rise of the Sierra Nevada further west. Yet for some reason not fully understood, the neighboring Colorado Plateau was able to preserve its structural integrity and remained a single tectonic block.

A second mystery was that while the lower layers of the Plateau appeared to be sinking, overall the Plateau was rising. The reason for this was discovered upon analyzing data from the USARRAY project. It was found that the asthenosphere had invaded the overlying lithosphere. The asthenosphere erodes the lower levels of the Plateau. At the same time, as it cools, it expands and lifts the upper layers of the Plateau.[14] Eventually, the great block of Colorado Plateau crust rose a kilometer higher than the Basin and Range. As the land rose, the streams responded by cutting ever deeper stream channels. The most well-known of these streams, the Colorado River, began to carve the Grand Canyon less than 6 million years ago in response to sagging caused by the opening of the Gulf of California to the southwest.

The Pleistocene epoch brought periodic ice ages and a cooler, wetter climate. This increased erosion at higher elevations with the introduction of alpine glaciers while mid-elevations were attacked by frost wedging and lower areas by more vigorous stream scouring. Pluvial lakes also formed during this time. Glaciers and pluvial lakes disappeared and the climate warmed and became drier with the start of Holocene epoch.

Energy generation

Electrical power generation is one of the major industries that takes place in the Colorado Plateau region. Most electrical generation comes from coal fired power plants.

Natural resources

Petroleum

The rocks of the Colorado Plateau are a source of oil and a major source of natural gas. Major petroleum deposits are present in the San Juan Basin of New Mexico and Colorado, the Uinta Basin of Utah, the Piceance Basin of Colorado, and the Paradox Basin of Utah, Colorado, and Arizona.Uranium

The Colorado Plateau holds major uranium deposits, and there was a uranium boom in the 1950s. The Atlas Uranium Mill near Moab has left a problematic tailings pile for cleanup,which is soon to happen.Coal

Major coal deposits are being mined in the Colorado Plateau in Utah, Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico, though large coal mining projects, such as on the Kaiparowits Plateau, have been proposed and defeated politically. The ITT Power Project, eventually located in Lynndyl, Utah, near Delta, was originally suggested for Salt Wash near Capitol Reef National Park. After a firestorm of opposition, it was moved to a less beloved site. In Utah the largest deposits are in aptly named Carbon County. In Arizona the biggest operation is on Black Mesa, supplying coal to Navajo Power Plant.Gilsonite and uintaite

Perhaps the only one of its kind, a gilsonite plant near Bonanza, southeast of Vernal, Utah, mines this unique, lustrous, brittle form of asphalt, for use in "varnishes, paints,...ink, waterproofing compounds, electrical insulation,...roofing materials."[15]Scenic beauty

The scenic appeal of this unique landscape had become, well before the end of the twentieth century, its greatest financial natural resource. The amount of commercial benefit to the four states of the Colorado Plateau from tourism exceeded that of any other natural resource.[citation needed]Protected lands

This relatively high semi-arid province produces many distinctive erosional features such as arches, arroyos, canyons, cliffs, fins, natural bridges, pinnacles, hoodoos, and monoliths that, in various places and extents, have been protected. Also protected are areas of historic or cultural significance, such as the pueblos of the Anasazi culture. There are nine U.S. National Parks, a National Historical Park, sixteen U.S. National Monuments and dozens of wilderness areas in the province along with millions of acres in U.S. National Forests, many state parks, and other protected lands. In fact, this region has the highest concentration of parklands in North America.[16] Lake Powell, in foreground, is not a natural lake but a reservoir impounded by Glen Canyon Dam.

National parks (from south to north to south clockwise):

- Petrified Forest National Park

- Grand Canyon National Park

- Zion National Park

- Bryce Canyon National Park

- Capitol Reef National Park

- Canyonlands National Park

- Arches National Park

- Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park

- Mesa Verde National Park

- Chaco Culture National Historical Park

- Aztec Ruins National Monument

- Canyon De Chelly National Monument

- Canyons of the Ancients National Monument

- Cedar Breaks National Monument

- Colorado National Monument

- Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument

- Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

- El Malpais National Monument

- El Morro National Monument

- Hovenweep National Monument

- Navajo National Monument

- Natural Bridges National Monument

- Rainbow Bridge National Monument

- Sunset Crater National Monument

- Vermilion Cliffs National Monument

- Walnut Canyon National Monument

- Wupatki National Monument

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Dead Horse Point State Park, Goosenecks State Park, the San Rafael Swell, the Grand Gulch Primitive Area, Kodachrome Basin State Park, Goblin Valley State Park, Monument Valley, and Barringer Crater.

Sedona, Arizona and Oak Creek Canyon lie on the south-central border of the Plateau. Many but not all of the Sedona area's cliff formations are protected as wilderness. The area has the visual appeal of a national park, but with a small, rapidly growing town in the center.

A research team lead by Dr. Christian Sonne, who works at Aarhus University in Denmark, reported their findings in a paper called "Penile density and globally used chemicals in Canadian and Greenland polar bears (link is external)" in the journal Environmental Research. They conclude in the abstract to this essay, "While reductions in BMD (bone mineral density) is in general unhealthy, reductions in penile BMD could lead to increased risk of species extinction because of mating and subsequent fertilization failure as a result of weak penile bones and risk of fractures. Based on this, future studies should assess how polar bear subpopulations respond upon EDC exposure since information and understanding about their circumpolar reproductive health is vital for future conservation."

Hard and unhard times for polar bears

Based on these findings, the title of the print version of the New Scientist essay could well have been "Unhard times for polar bears." On a more serious note, this landmark study shows just how much we affect the lives of other animals in unimaginable ways, making for hard times and threatening their very survival. Polar bears and many other species are getting screwed, or not, and what's even more egregious is that PCBs are very slow to break down, they disperse and accumulate over time. As the authors of this paper note, many pollutants "are known to be endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and are also known to be long-range dispersed and to biomagnify to very high concentrations in the tissues of Arctic apex predators such as polar bears (Ursus maritimus). A major concern relating to EDCs is their effects on vital organ–tissues such as bone and it is possible that EDCs represent a more serious challenge to the species' survival than the more conventionally proposed prey reductions linked to climate change."

I hope that this study is taken more seriously than others that clearly show just how harmful environmental pollutants can be, and more than lip service is given to banning their use and trying to reduce their presence. Polar bears are the poster animals for just how destructive we can be, and their loss is a very sad occurrence as we trounce ecosystem upon ecosystem and their magnificent residents.

Marc Bekoff's latest books are Jasper's story: Saving moon bears (with Jill Robinson), Ignoring nature no more: The case for compassionate conservation, Why dogs hump and bees get depressed, and Rewilding our hearts: Building pathways of compassion and coexistence. The Jane effect: Celebrating Jane Goodall (edited with Dale Peterson) has recently been published. (marcbekoff.com; @MarcBekoff)