|

|

Cosmologists distinguish between the observable universe and the global universe. The observable universe consists of the part of the universe that can, in principle, be observed by light reaching Earth within the age of the universe. It encompasses a region of space which currently forms a ball centered at Earth of estimated radius 46 billion light-years (4.4×1026 m). This does not mean the universe is 46 billion years old; in fact the universe is believed to be 13.799 billion years old but space itself has also expanded causing the size of the observable universe to be as stated. (However, it is possible to observe these distant areas only in their very distant past, when the distance light had to travel was much less). Assuming an isotropic nature, the observable universe is similar for all contemporary vantage points.

According to the book Our Mathematical Universe[clarification needed], the shape of the global universe can be explained with three categories:[1]

- Finite or infinite

- Flat (no curvature), open (negative curvature), or closed (positive curvature)

- Connectivity, how the universe is put together, i.e., simply connected space or multiply connected.

The exact shape is still a matter of debate in physical cosmology, but experimental data from various, independent sources (WMAP, BOOMERanG, and Planck for example) confirm that the observable universe is flat with only a 0.4% margin of error.[3][4][5] Theorists have been trying to construct a formal mathematical model of the shape of the universe. In formal terms, this is a 3-manifold model corresponding to the spatial section (in comoving coordinates) of the 4-dimensional space-time of the universe. The model most theorists currently use is the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) model. Arguments have been put forward that the observational data best fit with the conclusion that the shape of the global universe is infinite and flat,[6] but the data are also consistent with other possible shapes, such as the so-called Poincaré dodecahedral space[7][8] and the Sokolov-Starobinskii space (quotient of the upper half-space model of hyperbolic space by 2-dimensional lattice).[9]

Shape of the observable universe

As stated in the introduction, there are two aspects to consider:- its local geometry, which predominantly concerns the curvature of the universe, particularly the observable universe, and

- its global geometry, which concerns the topology of the universe as a whole.

If the observable universe encompasses the entire universe, we may be able to determine the global structure of the entire universe by observation. However, if the observable universe is smaller than the entire universe, our observations will be limited to only a part of the whole, and we may not be able to determine its global geometry through measurement. From experiments, it is possible to construct different mathematical models of the global geometry of the entire universe all of which are consistent with current observational data and so it is currently unknown whether the observable universe is identical to the global universe or it is instead many orders of magnitude smaller than it. The universe may be small in some dimensions and not in others (analogous to the way a cuboid is longer in the dimension of length than it is in the dimensions of width and depth). To test whether a given mathematical model describes the universe accurately, scientists look for the model's novel implications—what are some phenomena in the universe that we have not yet observed, but that must exist if the model is correct—and they devise experiments to test whether those phenomena occur or not. For example, if the universe is a small closed loop, one would expect to see multiple images of an object in the sky, although not necessarily images of the same age.

Cosmologists normally work with a given space-like slice of spacetime called the comoving coordinates, the existence of a preferred set of which is possible and widely accepted in present-day physical cosmology. The section of spacetime that can be observed is the backward light cone (all points within the cosmic light horizon, given time to reach a given observer), while the related term Hubble volume can be used to describe either the past light cone or comoving space up to the surface of last scattering. To speak of "the shape of the universe (at a point in time)" is ontologically naive from the point of view of special relativity alone: due to the relativity of simultaneity we cannot speak of different points in space as being "at the same point in time" nor, therefore, of "the shape of the universe at a point in time". However, the comoving coordinates (if well-defined) provide a strict sense to those by using the time since the Big Bang (measured in the reference of CMB) as a distinguished universal time.

Curvature of the universe

The curvature is a quantity describing how the geometry of a space differs locally from the one of the flat space. The curvature of any locally isotropic space (and hence of a locally isotropic universe) falls into one of the three following cases:- Zero curvature (flat); a drawn triangle's angles add up to 180° and the Pythagorean theorem holds; such 3-dimensional space is locally modeled by Euclidean space E3.

- Positive curvature; a drawn triangle's angles add up to more than 180°; such 3-dimensional space is locally modeled by a region of a 3-sphere S3.

- Negative curvature; a drawn triangle's angles add up to less than 180°; such 3-dimensional space is locally modeled by a region of a hyperbolic space H3.

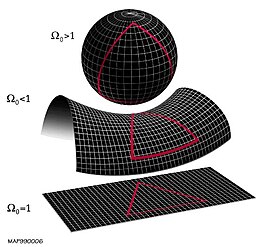

The local geometry of the universe is determined by whether the density parameter Ω is greater than, less than, or equal to 1.

From top to bottom: a spherical universe with Ω > 1, a hyperbolic universe with Ω < 1, and a flat universe with Ω = 1. These depictions of two-dimensional surfaces are merely easily visualizable analogs to the 3-dimensional structure of (local) space.

From top to bottom: a spherical universe with Ω > 1, a hyperbolic universe with Ω < 1, and a flat universe with Ω = 1. These depictions of two-dimensional surfaces are merely easily visualizable analogs to the 3-dimensional structure of (local) space.

General relativity explains that mass and energy bend the curvature of spacetime and is used to determine what curvature the universe has by using a value called the density parameter, represented with Omega (Ω). The density parameter is the average density of the universe divided by the critical energy density, that is, the mass energy needed for a universe to be flat. Put another way,

- If Ω = 1, the universe is flat

- If Ω > 1, there is positive curvature

- if Ω < 1 there is negative curvature

Ωmass ≈ 0.315±0.018

Ωrelativistic ≈ 9.24×10−5

ΩΛ ≈ 0.6817±0.0018

Ωtotal= Ωmass + Ωrelativistic + ΩΛ= 1.00±0.02

The actual value for critical density value is measured as ρcritical= 9.47×10−27 kg m−3. From these values, within experimental error, the universe seems to be flat.

Another way to measure Ω is to do so geometrically by measuring an angle across the observable universe. We can do this by using the CMB and measuring the power spectrum and temperature anisotropy. For an intuition, one can imagine finding a gas cloud that is not in thermal equilibrium due to being so large that light speed cannot propagate the thermal information. Knowing this propagation speed, we then know the size of the gas cloud as well as the distance to the gas cloud, we then have two sides of a triangle and can then determine the angles. Using a method similar to this, the BOOMERanG experiment has determined that the sum of the angles to 180° within experimental error, corresponding to an Ωtotal ≈ 1.00±0.12.[12]

These and other astronomical measurements constrain the spatial curvature to be very close to zero, although they do not constrain its sign. This means that although the local geometries of spacetime are generated by the theory of relativity based on spacetime intervals, we can approximate 3-space by the familiar Euclidean geometry.

The Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) model using Friedmann equations is commonly used to model the universe. The FLRW model provides a curvature of the universe based on the mathematics of fluid dynamics, that is, modeling the matter within the universe as a perfect fluid. Although stars and structures of mass can be introduced into an "almost FLRW" model, a strictly FLRW model is used to approximate the local geometry of the observable universe. Another way of saying this is that if all forms of dark energy are ignored, then the curvature of the universe can be determined by measuring the average density of matter within it, assuming that all matter is evenly distributed (rather than the distortions caused by 'dense' objects such as galaxies). This assumption is justified by the observations that, while the universe is "weakly" inhomogeneous and anisotropic (see the large-scale structure of the cosmos), it is on average homogeneous and isotropic.

Global universe structure

-13 —

–

-12 —

–

-11 —

–

-10 —

–

-9 —

–

-8 —

–

-7 —

–

-6 —

–

-5 —

–

-4 —

–

-3 —

–

-2 —

–

-1 —

–

0 —

As stated in the introduction, investigations within the study of the global structure of the universe include:

- Whether the universe is infinite or finite in extent

- Whether the geometry of the global universe is flat, positively curved, or negatively curved

- Whether the topology is simply connected like a sphere or multiply connected, like a torus[13]

Infinite or finite

One of the presently unanswered questions about the universe is whether it is infinite or finite in extent. For intuition, it can be understood that a finite universe has a finite volume that, for example, could be in theory filled up with a finite amount of material, while an infinite universe is unbounded and no numerical volume could possibly fill it. Mathematically, the question of whether the universe is infinite or finite is referred to as boundedness. An infinite universe (unbounded metric space) means that there are points arbitrarily far apart: for any distance d, there are points that are of a distance at least d apart. A finite universe is a bounded metric space, where there is some distance d such that all points are within distance d of each other. The smallest such d is called the diameter of the universe, in which case the universe has a well-defined "volume" or "scale."With or without boundary

Assuming a finite universe, the universe can either have an edge or no edge. Many finite mathematical spaces, e.g., a disc, have an edge or boundary. Spaces that have an edge are difficult to treat, both conceptually and mathematically. Namely, it is very difficult to state what would happen at the edge of such a universe. For this reason, spaces that have an edge are typically excluded from consideration.However, there exist many finite spaces, such as the 3-sphere and 3-torus, which have no edges. Mathematically, these spaces are referred to as being compact without boundary. The term compact basically means that it is finite in extent ("bounded") and complete. The term "without boundary" means that the space has no edges. Moreover, so that calculus can be applied, the universe is typically assumed to be a differentiable manifold. A mathematical object that possesses all these properties, compact without boundary and differentiable, is termed a closed manifold. The 3-sphere and 3-torus are both closed manifolds.

Curvature

The curvature of the universe places constraints on the topology. If the spatial geometry is spherical, i.e., possess positive curvature, the topology is compact. For a flat (zero curvature) or a hyperbolic (negative curvature) spatial geometry, the topology can be either compact or infinite.[14] Many textbooks erroneously state that a flat universe implies an infinite universe; however, the correct statement is that a flat universe that is also simply connected implies an infinite universe.[14] For example, Euclidean space is flat, simply connected, and infinite, but the torus is flat, multiply connected, finite, and compact.In general, local to global theorems in Riemannian geometry relate the local geometry to the global geometry. If the local geometry has constant curvature, the global geometry is very constrained, as described in Thurston geometries.

The latest research shows that even the most powerful future experiments (like SKA, Planck..) will not be able to distinguish between flat, open and closed universe if the true value of cosmological curvature parameter is smaller than 10−4. If the true value of the cosmological curvature parameter is larger than 10−3 we will be able to distinguish between these three models even now.[15]

Results of the Planck mission released in 2015 show the cosmological curvature parameter, ΩK, to be 0.000±0.005, consistent with a flat universe.[16]

Universe with zero curvature

In a universe with zero curvature, the local geometry is flat. The most obvious global structure is that of Euclidean space, which is infinite in extent. Flat universes that are finite in extent include the torus and Klein bottle. Moreover, in three dimensions, there are 10 finite closed flat 3-manifolds, of which 6 are orientable and 4 are non-orientable. These are the Bieberbach manifolds. The most familiar is the aforementioned 3-torus universe.In the absence of dark energy, a flat universe expands forever but at a continually decelerating rate, with expansion asymptotically approaching zero. With dark energy, the expansion rate of the universe initially slows down, due to the effect of gravity, but eventually increases. The ultimate fate of the universe is the same as that of an open universe.

A flat universe can have zero total energy.

Universe with positive curvature

A positively curved universe is described by elliptic geometry, and can be thought of as a three-dimensional hypersphere, or some other spherical 3-manifold (such as the Poincaré dodecahedral space), all of which are quotients of the 3-sphere.Poincaré dodecahedral space, a positively curved space, colloquially described as "soccerball-shaped", as it is the quotient of the 3-sphere by the binary icosahedral group, which is very close to icosahedral symmetry, the symmetry of a soccer ball. This was proposed by Jean-Pierre Luminet and colleagues in 2003[7][17] and an optimal orientation on the sky for the model was estimated in 2008.[8]

Universe with negative curvature

Universe in an expanding sphere. The galaxies farthest away are moving fastest and hence experience length contraction and so become smaller to an observer in the centre.

A hyperbolic universe, one of a negative spatial curvature, is described by hyperbolic geometry, and can be thought of locally as a three-dimensional analog of an infinitely extended saddle shape. There are a great variety of hyperbolic 3-manifolds, and their classification is not completely understood. Those of finite volume can be understood via the Mostow rigidity theorem. For hyperbolic local geometry, many of the possible three-dimensional spaces are informally called "horn topologies", so called because of the shape of the pseudosphere, a canonical model of hyperbolic geometry. An example is the Picard horn, a negatively curved space, colloquially described as "funnel-shaped".[9]

Curvature: open or closed

When cosmologists speak of the universe as being "open" or "closed", they most commonly are referring to whether the curvature is negative or positive. These meanings of open and closed are different from the mathematical meaning of open and closed used for sets in topological spaces and for the mathematical meaning of open and closed manifolds, which gives rise to ambiguity and confusion. In mathematics, there are definitions for a closed manifold (i.e., compact without boundary) and open manifold (i.e., one that is not compact and without boundary). A "closed universe" is necessarily a closed manifold. An "open universe" can be either a closed or open manifold. For example, in the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) model the universe is considered to be without boundaries, in which case "compact universe" could describe a universe that is a closed manifold.Milne model ("spherical" expanding)

If one applies Minkowski space-based special relativity to expansion of the universe, without resorting to the concept of a curved spacetime, then one obtains the Milne model. Any spatial section of the universe of a constant age (the proper time elapsed from the Big Bang) will have a negative curvature; this is merely a pseudo-Euclidean geometric fact analogous to one that concentric spheres in the flat Euclidean space are nevertheless curved. Spatial geometry of this model is an unbounded hyperbolic space. The entire universe is contained within a light cone, namely the future cone of the Big Bang. For any given moment t> 0 of coordinate time (assuming the Big Bang has t = 0), the entire universe is bounded by a sphere of radius exactly c t. The apparent paradox of an infinite universe contained within a sphere is explained with length contraction: the galaxies farther away, which are travelling away from the observer the fastest, will appear thinner.This model is essentially a degenerate FLRW for Ω = 0. It is incompatible with observations that definitely rule out such a large negative spatial curvature. However, as a background in which gravitational fields (or gravitons) can operate, due to diffeomorphism invariance, the space on the macroscopic scale, is equivalent to any other (open) solution of Einstein's field equations.

![\rho_0[\varphi_t] = \exp{\left[-\frac{1}{\hbar}

\int\frac{d^3k}{(2\pi)^3}

\tilde\varphi_t^*(k)\sqrt{|k|^2+m^2}\;\tilde \varphi_t(k)\right]}.](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/957b1e970103b111dc5c5385a0061b699d795b25)

![\rho_E[\varphi_t] = \exp{[-H[\varphi_t]/k_\mathrm{B}T]}=\exp{\left[-\frac{1}{k_\mathrm{B}T} \int\frac{d^3k}{(2\pi)^3}

\tilde\varphi_t^*(k){\scriptstyle\frac{1}{2}}(|k|^2+m^2)\;\tilde \varphi_t(k)\right]}.](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c698c6d4af7d375bb19778cc836eabfe56505cf4)