A doctor draws blood from one of the Tuskegee test subjects.

The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, also known as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study or Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment (/tʌsˈkiːɡiː/ tus-KEE-ghee)[1] was an infamous clinical study conducted between 1932 and 1972 by the U.S. Public Health Service. The purpose of this study was to observe the natural progression of untreated syphilis in rural African-American men in Alabama under the guise of receiving free health care from the United States government.[1] The study was conducted to understand the disease's natural history throughout time and to also determine proper treatment dosage for specific people and the best time to receive injections of treatments.[2]

The Public Health Service started working on this study in 1932 in collaboration with Tuskegee University, a historically black college in Alabama. Investigators enrolled in the study a total of 622 impoverished, African-American sharecroppers from Macon County, Alabama. Of these men, 431 had previously contracted syphilis before the study began, and 169[3] did not have the disease. The men were given free medical care, meals, and free burial insurance for participating in the study. The men were told that the study was only going to last six months, but it actually lasted 40 years.[4] After funding for treatment was lost, the study was continued without informing the men that they would never be treated. None of the men infected were ever told that they had the disease, and none were treated with penicillin even after the antibiotic was proven to successfully treat syphilis. According to the Centers for Disease Control, the men were told that they were being treated for "bad blood", a colloquialism that described various conditions such as syphilis, anemia, and fatigue. "Bad blood"—specifically the collection of illnesses the term included—was a leading cause of death within the southern African-American community.[4]

The 40-year study was controversial for reasons related to ethical standards. Researchers knowingly failed to treat patients appropriately after the 1940s validation of penicillin was found as an effective cure for the disease that they were studying. The revelation in 1972 of study failures by a whistleblower, Peter Buxtun, led to major changes in U.S. law and regulation on the protection of participants in clinical studies. Now studies require informed consent,[5] communication of diagnosis, and accurate reporting of test results.[6]

By 1947, penicillin had become the standard treatment for syphilis. Choices available to the doctors involved in the study might have included treating all syphilitic subjects and closing the study, or splitting off a control group for testing with penicillin. Instead, the Tuskegee scientists continued the study without treating any participants; they withheld penicillin and information about it from the patients. In addition, scientists prevented participants from accessing syphilis treatment programs available to other residents in the area.[7] The study continued, under numerous US Public Health Service supervisors, until 1972, when a leak to the press resulted in its termination on November 16 of that year.[8] The victims of the study, all African American, included numerous men who died of syphilis, 40 wives who contracted the disease, and 19 children born with congenital syphilis.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, cited as "arguably the most infamous biomedical research study in U.S. history",[9] led to the 1979 Belmont Report and to the establishment of the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP).[10] It also led to federal laws and regulations requiring Institutional Review Boards for the protection of human subjects in studies involving them. The Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) manages this responsibility within the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).[11]

In 1993, President Bill Clinton formally apologized on behalf of the United States to victims of the experiment.

History

Study clinicians

For the most part, doctors and civil servants simply did their jobs. Some merely followed orders, others worked for the glory of science.

— John R. Heller Jr., Director of the Public Health Service's Division of Venereal Diseases[12]

Oliver Wenger

The venereal disease section of the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) formed a study group in 1932 at its national headquarters. Taliaferro Clark was credited with founding it. His initial goal was to follow untreated syphilis in a group of black men for 6 to 9 months, and then follow up with a treatment phase.[13] When he understood the intention of other study members to use deceptive practices, Clark disagreed with the plan to conduct an extended study.[clarification needed] He retired the year after the study began.

Although Clark is usually assigned blame for conceiving the Tuskegee Study, Thomas Parran Jr. is equally, if not more, deserving of originating the notion of a non-treatment experiment in Macon County, Alabama. As the Health Commissioner of New York State (and former head of the PHS Venereal Disease Division), Parran was asked by the Rosenwald Fund to make an assessment of their survey and demonstration projects in six Southern states. Among his conclusions was the recommendation that, “If one wished to study the natural history of syphilis in the Negro race uninfluenced by treatment, this county (Macon) would be an ideal location for such a study.”[14]

Representing the PHS, Clark had solicited the participation of the Tuskegee Institute (a well-known historically black college in Alabama, now known as Tuskegee University) and of the Arkansas regional Public Health Service office. Eugene Heriot Dibble, Jr., an African-American doctor, was head of the John Andrew Hospital at the Tuskegee Institute. (From 1936-1946, he served as director of the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Medical Center, established in 1923 in the city by the federal government on land donated by the Institute.)

Oliver C. Wenger was the director of the regional PHS Venereal Disease Clinic in Hot Springs, Arkansas. He and his staff took the lead in developing study procedures. Wenger and his staff played a critical role in developing early study protocols. Wenger continued to advise and assist the Tuskegee Study when it was adapted as a long-term, no-treatment observational study after funding for treatment was lost.[15]

Raymond A. Vonderlehr was appointed on-site director of the research program and developed the policies that shaped the long-term follow-up section of the project. His method of gaining the "consent" of the subjects for spinal taps (to look for signs of neurosyphilis) was by portraying this diagnostic test as a "special free treatment". Participants were not told their diagnosis. Vonderlehr retired as head of the venereal disease section in 1943, shortly after the antibiotic penicillin had first been shown to be a cure for syphilis.

Several African American health workers and educators associated with Tuskegee Institute helped the PHS to carry out its experimentation and played a critical role in the progress of the study. The extent to which they knew about the full scope of the study is not clear in all cases. Robert Russa Moton, then president of Tuskegee Institute, and Eugene Dibble, head of the Institute's John Andrews Hospital, both lent their endorsement and institutional resources to the government study. Registered nurse Eunice Rivers, who had trained at Tuskegee Institute and worked at its affiliated John Andrew Hospital, was recruited at the start of the study to be the main contact with the participants in the study.

Vonderlehr advocated for Rivers' participation, as the direct link to the regional African-American community. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Tuskegee Study recruited poor lower-class African Americans, who often could not afford health care, by offering them the chance to join "Miss Rivers' Lodge". Patients were told they would receive free physical examinations at Tuskegee University, free rides to and from the clinic, hot meals on examination days, and free treatment for minor ailments.

Based on the available health care resources, Rivers believed that the benefits of the study to the men outweighed the risks. As the study became long term, Rivers became the chief person with continuity. Unlike the national, regional and on-site PHS administrators, doctors, and researchers, some of whom were political appointees with short tenure and others who changed jobs, Rivers continued at Tuskegee University. She was the only study staff person to work with participants for the full 40 years. By the 1950s, Nurse Rivers had become pivotal to the study: her personal knowledge of the subjects enabled maintenance of long-term follow up.

In 1943, Congress passed the Henderson Act, a public health law requiring testing and treatment for venereal disease. By the late 1940s, doctors, hospitals and public health centers throughout the country routinely treated diagnosed syphilis with penicillin. However, the Tuskegee experiment continued to avoid treating the men who had the disease.

In the period following World War II, the revelation of the Holocaust and related Nazi medical abuses brought about changes in international law. Western allies formulated the Nuremberg Code to protect the rights of research subjects. In 1964 the World Health Organization's Declaration of Helsinki specified that experiments involving human beings needed the "informed consent" of participants. But no one appeared to have reevaluated the protocols of the Tuskegee Study according to the new standards and in light of treatment available for the disease which is fatal 8–58% of the time. On July 25, 1972, word of the Tuskegee Study was reported by Jean Heller of the Associated Press; the next day The New York Times carried it on its front page, and the story captured national attention. Peter Buxtun, a whistleblower who was a former PHS interviewer for venereal disease, had leaked information after failing to get a response to his protests about the study within the department. He gave information to the Washington Star and The New York Times. John R. Heller Jr. of PHS, who in later years of the study led the national division, still defended the ethics of the study, stating, "The longer the study, the better the ultimate information we would derive."[16] Author James Jones editorialized about Heller, suggesting that his opinion was, "The men's status did not warrant ethical debate. They were subjects, not patients; clinical material, not sick people."[17]

Study details

Subject blood draw, c. 1953

A Norwegian study in 1928 had reported on the pathologic manifestations of untreated syphilis in several hundred white males. This study is known as a retrospective study, since investigators pieced together information from the histories of patients who had already contracted syphilis but remained untreated for some time.

Subjects talking with study coordinator, Nurse Eunice Rivers, c.1970

The Tuskegee study group decided to build on the Oslo work and perform a prospective study to complement it. Researchers could study the natural progression of the disease as long as they did not harm their subjects. The researchers involved with the Tuskegee experiment reasoned that they were not harming the black men involved in the study because they were unlikely to get treatment for their syphilis and further education would not diminish their inherent sex drive. Even at the beginning of the study, major medical textbooks had recommended that all syphilis be treated, as the consequences were quite severe. At that time, treatment included arsenic therapy and the "606" formula.[18] The researchers reasoned that the knowledge gained would benefit humankind; however, it was determined afterward that the doctors did harm their subjects by depriving them of appropriate treatment once it had been discovered. The study was characterized as "the longest non-therapeutic experiment on human beings in medical history."[7]

The US Public Health Study of Syphilis at Tuskegee began as a 6-month descriptive epidemiological study of the range of pathology associated with syphilis in the Macon County population. At that time, it was believed that the effects of syphilis depended on the race of those affected. For African Americans, physicians believed that their cardiovascular system was more affected than the central nervous system.[19] Initially, subjects were studied for six to eight months and then treated with contemporary methods, including Salvarsan, mercurial ointments, and bismuth. These methods were, at best, mildly effective. The disadvantage was that these treatments were all highly toxic. The Tuskegee Institute participated in the study, as its representatives understood the intent was to benefit public health in the local poor population.[20] The Tuskegee University-affiliated hospital effectively loaned the PHS its medical facilities, and other predominantly black institutions and local black doctors participated as well.

The Rosenwald Fund, a major Chicago-based philanthropy devoted to black education and community development in the South, provided financial support to pay for the eventual treatment of the patients. They had previously collaborated with Public Health Services in a study of syphilis prevalence in over 2,000 black workers in Mississippi's Delta Pine and Land Company in 1928, and helped provide treatment for 25% of the workers who had tested positive for the disease.[21] Study researchers initially recruited 399 syphilitic Black men, and 201 healthy Black men as controls.

Table from U.S. Public Health Service summarising participants in the study

Continuing effects of the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the beginning of the Great Depression led the Rosenwald Fund to withdraw its offer of funding. Study directors issued a final report as they thought this might mean the end of the study once funding to buy medication for the treatment phase of the study was withdrawn.

Medical ethics considerations were limited from the start and rapidly deteriorated. The PHS asked black Tuskegee Institute physicians to participate in the study by offering funds, employment, and interns to encourage the ongoing participation of the patients. Additionally, the study intentionally employed Eunice Rivers, a black nurse from Macon County, to be primary source of contact and build personal, trusting relationships with patients to promote their participation.[21] To ensure that the men would show up for the possibly dangerous, painful, diagnostic, and non-therapeutic spinal taps, the doctors sent the 400 patients a misleading letter titled "Last Chance for Special Free Treatment". The study also required all participants to undergo an autopsy after death in order to receive funeral benefits. After penicillin was discovered as a cure, researchers continued to deny such treatment to many study participants. Many patients were lied to and given placebo treatments so that researchers could observe the full, long-term progression of the fatal disease.[20]

Taking a blood sample as part of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study

The Tuskegee Study published its first clinical data in 1934 and issued its first major report in 1936. This was prior to the discovery of penicillin as a safe and effective treatment for syphilis. The study was not secret since reports and data sets were published to the medical community throughout its duration.

During World War II, 250 of the subject men registered for the draft. These men were consequently diagnosed as having syphilis at military induction centers and ordered to obtain treatment for syphilis before they could be taken into the armed services.[22] PHS researchers attempted to prevent these men from getting treatment, thus depriving them of chances for a cure. A PHS representative was quoted at the time saying: "So far, we are keeping the known positive patients from getting treatment."[22] Despite this, 96% of the 90 original test subjects reexamined in 1963 had received either arsenical or penicillin treatments from another health provider.[23]

By 1947 penicillin had become standard therapy for syphilis. The US government sponsored several public health programs to form "rapid treatment centers" to eradicate the disease. When campaigns to eradicate venereal disease came to Macon County, study researchers prevented their patients from participating.[22]

By the end of the study in 1972, only 74 of the test subjects were alive. Of the original 399 men, 28 had died of syphilis, 100 were dead of related complications, 40 of their wives had been infected, and 19 of their children were born with congenital syphilis. The Tuskegee University Legacy Museum has on display a check issued by the United States government on behalf of Dan Carlis to Lloyd Clements, Jr., a descendant of one of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study participants.[24] Lloyd Clements, Jr.'s great-grandfather Dan Carlis and two of his uncles, Ludie Clements and Sylvester Carlis, were in the study. Original legal paper work for Sylvester Carlis related to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study is on display at the museum as well. Lloyd Clements, Jr. has worked with noted historian Susan Reverby concerning his family's involvement with the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

Study termination

Peter Buxtun, a PHS venereal disease investigator, the "whistleblower"

Group of Tuskegee Experiment test subjects

Charlie Pollard, survivor

Herman Shaw, survivor

The first dissent against the Tuskegee study was Irwin Schatz, a young Chicago doctor only four years out of medical school. In 1965, Schatz read an article about the study in a medical journal, and wrote a letter directly to the study's authors confronting them with a declaration of brazen unethical practice.[25] His letter, read by Anne R. Yobs (one of the study's authors), was immediately ignored and filed away with a brief memo that no reply would be sent.[26]

In 1966 Peter Buxtun, a PHS venereal-disease investigator in San Francisco, sent a letter to the national director of the Division of Venereal Diseases to express his concerns about the ethics and morality of the extended Tuskegee Study. The Center for Disease Control (CDC), which by then controlled the study, reaffirmed the need to continue the study until completion; i.e., until all subjects had died and been autopsied. To bolster its position, the CDC received unequivocal support for the continuation of the study, both from local chapters of the National Medical Association (representing African-American physicians) and the American Medical Association (AMA).

In 1968 William Carter Jenkins, an African-American statistician in the PHS, part of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), founded and edited The Drum, a newsletter devoted to ending racial discrimination in HEW. The cabinet-level department included the CDC. In The Drum, Jenkins called for an end to the Tuskegee Study. He did not succeed; it is not clear who read his work.[27]

Buxtun finally went to the press in the early 1970s. The story broke first in the Washington Star on July 25, 1972. It became front-page news in the New York Times the following day. Senator Edward Kennedy called Congressional hearings, at which Buxtun and HEW officials testified. As a result of public outcry, the CDC and PHS appointed an ad hoc advisory panel to review the study. The panel found that the men agreed to certain terms of the experiment, such as examination and treatment. However, they were not informed of the study's actual purpose.[1] The panel then determined the study was medically unjustified and ordered its termination.

As part of the settlement of a class action lawsuit subsequently filed by the NAACP on behalf of study participants and their descendants, the U.S. government paid $10 million ($49.6 million in 2017) and agreed to provide free medical treatment to surviving participants and to surviving family members infected as a consequence of the study; Congress created a commission empowered to write regulations to deter such abuses from occurring in the future.[28]

A collection of materials compiled to investigate the study is held at the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland.[29]

Aftermath

In 1974 Congress passed the National Research Act and created a commission to study and write regulations governing studies involving human participants. Within the US Department of Health and Human Services, the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) was established to oversee clinical trials. Now studies require informed consent,[5] communication of diagnosis, and accurate reporting of test results.[6] Institutional review boards (IRBs), including laypeople, are established in scientific research groups and hospitals to review study protocols and protect patient interests, to ensure that participants are fully informed.In 1994, a multi-disciplinary symposium was held on the Tuskegee study: Doing Bad in the Name of Good?: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study and Its Legacy at the University of Virginia. Following that, interested parties formed the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee to develop ideas that had arisen at the symposium. It issued its final report in May 1996.[30] The Committee had two related goals: (1) President Bill Clinton should publicly apologize for past government wrongdoing related to the study and (2) the Committee and relevant federal agencies should develop a strategy to redress the damages.[31]

A year later on May 16, 1997, President Bill Clinton formally apologized and held a ceremony at the White House for surviving Tuskegee study participants. He said:

What was done cannot be undone. But we can end the silence. We can stop turning our heads away. We can look at you in the eye and finally say on behalf of the American people, what the United States government did was shameful, and I am sorry ... To our African American citizens, I am sorry that your federal government orchestrated a study so clearly racist.[32]Five of the eight study survivors attended the White House ceremony.

The presidential apology led to progress in addressing the second goal of the Legacy Committee. The federal government contributed to establishing the National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care at Tuskegee, which officially opened in 1999 to explore issues that underlie research and medical care of African Americans and other under-served people.[33]

In 2009 the Legacy Museum opened in the Bioethics Center, to honor the hundreds of participants of the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.[33][34]

The revelations of mistreatment under the Tuskegee Syphilis Study are believed to have significantly damaged the trust of the black community toward public health efforts in the United States.[35][36] Observers believe that the abuses of the study may have contributed to the reluctance of many poor black people to seek routine preventive care.[37][36] A 1999 survey showed that 80% of African American men believe the men in the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment had been injected with syphilis.[38] A 2016 paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research finds "that the historical disclosure of the [Tuskegee experiment] in 1972 is correlated with increases in medical mistrust and mortality and decreases in both outpatient and inpatient physician interactions for older black men. Our estimates imply life expectancy at age 45 for black men fell by up to 1.4 years in response to the disclosure, accounting for approximately 35% of the 1980 life expectancy gap between black and white men."[36] However, other studies, such as the Tuskegee Legacy Project Questionnaire, have challenged the degree to which knowledge of the Tuskegee experiments have kept black Americans from participating in medical research.[39] This study shows that, even though black Americans are four times more likely to know about the Syphilis trials than are whites, they are two to three times more willing to participate in biomedical studies.[40] Other studies concluded that the Tuskegee Syphilis trial has played a minor role in the decisions of black Americans to decline participation as research subjects.[41] Of the studies that have investigated the willingness of black Americans to participate in medical studies, they have not drawn consistent conclusions related to the willingness and participation in studies by racial minorities. Some of the factors that continue to limit the credibility of these few studies is how awareness differs significantly across studies. For instance, it appears that the rates of awareness differ as a function of method of assessment, study participants who reported awareness of the Tuskegee Syphilis Trials are often misinformed about the results and issues, and awareness of the study is not reliably associated with unwillingness to participate in scientific research.[42][43][44][45][46]

Distrust of the government, in part formed through the study, contributed to persistent rumors during the 1980s in the black community that the government was responsible for the HIV/AIDS crisis by having deliberately introduced the virus to the black community as some kind of experiment.[47] In February 1992 on ABC's Prime Time Live, journalist Jay Schadler interviewed Dr. Sidney Olansky, Public Health Services director of the study from 1950 to 1957. When asked about the lies that were told to the study subjects, Olansky said, "The fact that they were illiterate was helpful, too, because they couldn't read the newspapers. If they were not, as things moved on they might have been reading newspapers and seen what was going on."[21]

Ethical implications

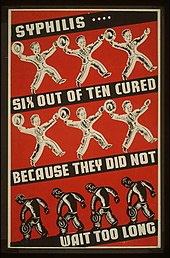

Depression-era U.S. poster advocating early syphilis treatment. Although

treatments were available, participants in the study did not receive

them.

Tuskegee highlighted issues in race and science.[48] The aftershocks of this study, and other human experiments in the United States, led to the establishment of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research and the National Research Act. The latter requires the establishment of institutional review boards (IRBs) at institutions receiving federal support (such as grants, cooperative agreements, or contracts). Foreign consent procedures can be substituted which offer similar protections and must be submitted to the Federal Register unless a statute or Executive Order requires otherwise.

Writer James Jones said that physicians were fixated on African American sexuality, and believing that African Americans willingly had sexual relations with those who were infected (although none had been told his diagnosis) resulted in their believing that individuals were solely responsible for contracting the disease.[49] One researcher critiqued how the study was administered and its change in purpose. He said that it was "the economic exploitation of humans as a natural resource of a disease that could not be cultivated or animals in order to establish and sustain U.S. superiority in patented commercial biotechnology".[50]

Due to the lack of information, the participants were manipulated into continuing the study without full knowledge of their role or their choices.[51] Since the late 20th century, IRBs established in association with clinical studies require that all involved in study be willing and voluntary participants.[52][53]

In popular culture

- The lyrics of Gil Scott-Heron's 33-second song, "Tuskeegee #626", featured on the Bridges (1977) LP, detail and condemn the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiments.

- David Feldshuh wrote a stage play based on the history of the Tuskegee study, titled Miss Evers' Boys (1992). It was a runner-up for the 1992 Pulitzer Prize in drama.[54] In 1997 it was adapted as an HBO made-for-TV movie. The HBO adaptation was nominated for eleven Emmy Awards,[55] and won in four categories.[56]

- Hip hop duo Pete Rock & CL Smooth reference the experiments in the song "Anger in the Nation", from their Mecca and the Soul Brother (1992) LP.

- The Tuskegee trials inspired a seven-issue Marvel comic book series, Truth: Red, White, and Black (published January – July 2003), written as a prequel to the Captain America series. Truth: Red, White, and Black explores the exploitation of certain races for scientific research, as in the Tuskegee syphilis trials.[40]

- In the movie Half Baked the character Thurgood Jenkins made reference that his grandfather was in the Tuskegee experiments.