Holism (from Greek ὅλος holos "all, whole, entire") is the idea that systems (physical, biological, chemical, social, economic, mental, linguistic) and their properties should be viewed as wholes, not just as a collection of parts.[1][2]

The term holism was coined by J. C. Smuts in Holism and Evolution.[3][4] It was Smuts' opinion that holism is a concept that represents all of the wholes in the universe, and these wholes are the real factors in the universe. Further, that Holism also denoted a theory of the universe in the same vein as Materialism and Spiritualism.[3]:120–121

Synopsis of Holism and Evolution

After identifying the need for reform in the fundamental concepts of matter, life and mind (chapter 1) Smuts examines the reformed concepts (as of 1926) of space and time (chapter 2), matter (chapter 3) and biology (chapter 4) and concludes that the close approach to each other of the concepts of matter, life and mind, and the partial overflow of each other's domain, implies that there is a fundamental principle (Holism) of which they are the progressive outcome.[3]:86 Chapters 5 and 6 provide the general concept, functions and categories of Holism; chapters 7 and 8 address Holism with respect to Mechanism and Darwinism, chapters 9-11 make a start towards demonstrating the concepts and functions of Holism for the metaphysical categories (mind, personality, ideals) and the book concludes with a chapter that argues for the universal ubiquity of Holism and its place as a monistic ontology.The following is an overview of Smuts' opinions regarding the general concept, functions, and categories of Holism; like the definition of Holism, other than the idea that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, the editor is unaware of any authoritative secondary sources corroborating Smuts' opinions.

Structure

Wholes are composites which have an internal structure, function or character which clearly differentiates them from mechanical additions, aggregates, and constructions, such as science assumes on the mechanical hypothesis.[3]:106 The concept of structure is not confined to the physical domain (e.g. chemical, biological and artifacts); it also applies to the metaphysical domain (e.g. mental structures, properties, attributes, values, ideals, etc.)[3]:161Field

The field of a whole is not something different and additional to it, it is the continuation of the whole beyond its sensible contours of experience.[3]:113 The field characterizes a whole as a unified and synthesised event in the system of Relativity, that includes not only its present but also its past—and also its future potentialities.[3]:89 As such, the concept of field entails both activity and structure.[3]:115Variation

Darwin's theory of organic descent placed primary emphasis on the role of natural selection but there would be nothing to select if not for variation. Variations that are the result of mutations in the biological sense and variations that are the result of individually acquired modifications in the personal sense are attributed by Smuts to Holism; further it was his opinion that because variations appear in complexes and not singly, evolution is more than the outcome of individual selections, it is holistic.[3]:190–192Regulation

The whole exhibits a discernible regulatory function as it relates to cooperation and coordination of the structure and activity of parts, and to the selection and deselection of variations. The result is a balanced correlation of organs and functions. The activities of the parts are directed to central ends; co-operation and unified action instead of the separate mechanical activities of the parts.[3]:125Creativity

It is the intermingling of fields which is creative or causal in nature. This is seen in matter, where if not for its dynamic structural creative character matter could not have been the mother of the universe. This function, or factor of creativity is even more marked in biology where the protoplasm of the cell is vitally active in an ongoing process of creative change where parts are continually being destroyed and replaced by new protoplasm. With minds the regulatory function of Holism acquires consciousness and freedom, demonstrating a creative power of the most far-reaching character. Holism is not only creative but self-creative, and its final structures are far more holistic than its initial structures.[3]:18, 37, 67–68, 88–89Causality

As it relates to causality Smuts makes reference to A. N. Whitehead, and indirectly Baruch Spinoza; the Whitehead premise is that organic mechanism is a fundamental process which realizes and actualizes individual syntheses or unities. Holism (the factor) exemplifies this same idea while emphasizing the holistic character of the process. The whole completely transforms the concept of Causality; results are not directly a function of causes. The whole absorbs and integrates the cause into its own activity; results appear as the consequence of the activity of the whole.[3]:121–124,126 Note that this material relating to Whitehead's influence as it relates to causality was added in the second edition and, of course, will not be found in reprints of the first edition; nor is it included in the most recent Holst edition. It is the second edition of Holism and Evolution (1927) that provides the most recent and definitive treatment by Smuts.The whole is greater than the sum of its parts

The fundamental holistic characters as a unity of parts which is so close and intense as to be more than the sum of its parts; which not only gives a particular conformation or structure to the parts, but so relates and determines them in their synthesis that their functions are altered; the synthesis affects and determines the parts, so that they function towards the whole; and the whole and the parts, therefore reciprocally influence and determine each other, and appear more or less to merge their individual characters: the whole is in the parts and the parts are in the whole, and this synthesis of whole and parts is reflected in the holistic character of the functions of the parts as well as of the whole.[3]:88

Progressive grading of wholes

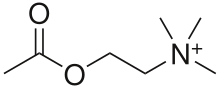

A "rough and provisional" summary of the progressive grading of wholes that comprise holism is as follows:[3]:109- Material structure e.g. a chemical compound

- Functional structure in living bodies

- Animals, which exhibit a degree of central control that is-primarily implicit and unconscious

- Personality, characterized as conscious central control

- States and similar group organizations characterized by central control that involves many people.

- Holistic Ideals, or absolute Values, distinct from human personality that are creative factors in the creation of a spiritual world, for example Truth, Beauty and Goodness.

Indications of holism in philosophy

In philosophy, any doctrine that emphasizes the priority of a whole over its parts is holism. Some suggest that such a definition owes its origins to a non-holistic view of language and places it in the reductivist camp. Alternately, a 'holistic' definition of holism denies the necessity of a division between the function of separate parts and the workings of the 'whole'. Effectively this means that the concept of a part has no absolute foundation in observation, but is rather a result of a materialist structuring of reality based on the necessity of logical and distinct units as a means to deriving information through comparative analysis. It suggests that the key recognizable characteristic of a concept of 'true' holism is a sense of the fundamental truth of any particular experience. This exists in contradistinction to what is perceived as the reductivist reliance on inductive method as the key to verification of its concept of how the parts function within the whole. Equally the potential for recognising the clarity of holistic experience within the logical terms of maths is limited by the abstract nature of numbers. In terms of real life measurements numbers have no scale or dimensional properties so have to rely on experimentally verified units (e.g. inches, volts, calories etc.), to describe reality. It is this reliance on the holistic integrity of experience which leads to the recognition that intuitive perception rather than mathematical calculation is the source of the truth of effective theories. (See references Holism, 2016.)Philosophy of language

In the philosophy of language this becomes the claim, called semantic holism, that the meaning of an individual word or sentence can only be understood in terms of its relations to a larger body of language, even a whole theory or a whole language. In the philosophy of mind, a mental state may be identified only in terms of its relations with others. This is often referred to as "content holism" or "holism of the mental". This notion involves the philosophies of such figures as Frege, Wittgenstein, and Quine.[5]Epistemological and confirmation holism

Epistemological and confirmation holism are mainstream ideas in contemporary philosophy.Ontological holism

Ontological holism was espoused by David Bohm in his theory[6] on the implicate and explicate order.Spinoza

The concept of holism played a pivotal role in Baruch Spinoza's philosophy.[7][8]Hegel

Hegel rejected "the fundamentally atomistic conception of the object," (Stern, 38) arguing that "individual objects exist as manifestations of indivisible substance-universals, which cannot be reduced to a set of properties or attributes; he therefore holds that the object should be treated as an ontologically primary whole." (Stern, 40) In direct opposition to Kant, therefore, "Hegel insists that the unity we find in our experience of the world is not constructed by us out of a plurality of intuitions." (Stern, 40) In "his ontological scheme a concrete individual is not reducible to a plurality of sensible properties, but rather exemplifies a substance universal." (Stern, 41) His point is that it is "a mistake to treat an organic substance like blood as nothing more than a compound of unchanging chemical elements, that can be separated and united without being fundamentally altered." (Stern, 103) In Hegel's view, a substance like blood is thus "more of an organic unity and cannot be understood as just an external composition of the sort of distinct substances that were discussed at the level of chemistry." (Stern, 103) Thus in Hegel's view, blood is blood and cannot be successfully reduced to what we consider are its component parts; we must view it as a whole substance entire unto itself. This is most certainly a fundamentally holistic view.[9]Indications of holism in physical science

Agriculture

There are several newer methods in agricultural science such as permaculture and holistic planned grazing (holistic management) that integrate ecology and social sciences with food production. Organic farming is sometimes considered a holistic approach.Chaos and complexity

In the latter half of the 20th century, holism led to systems thinking and its derivatives. Systems in biology, psychology, or sociology are frequently so complex that their behavior is, or appears, "new" or "emergent": it cannot be deduced from the properties of the elements alone.[10]Holism has thus been used as a catchword. This contributed to the resistance encountered by the scientific interpretation of holism, which insists that there are ontological reasons that prevent reductive models in principle from providing efficient algorithms for prediction of system behavior in certain classes of systems.[citation needed]

Scientific holism holds that the behavior of a system cannot be perfectly predicted, no matter how much data is available. Natural systems can produce surprisingly unexpected behavior, and it is suspected that behavior of such systems might be computationally irreducible, which means it would not be possible to even approximate the system state without a full simulation of all the events occurring in the system. Key properties of the higher level behavior of certain classes of systems may be mediated by rare "surprises" in the behavior of their elements due to the principle of interconnectivity, thus evading predictions except by brute force simulation.

Complexity theory (also called "science of complexity") is a contemporary heir of systems thinking. It comprises both computational and holistic, relational approaches towards understanding complex adaptive systems and, especially in the latter, its methods can be seen as the polar opposite to reductive methods. General theories of complexity have been proposed, and numerous complexity institutes and departments have sprung up around the world. The Santa Fe Institute is arguably the most famous of them.

Ecology

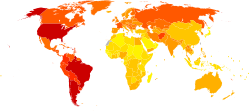

The Earth seen from Apollo 17.

Holistic thinking is often applied to ecology, combining biological, chemical, physical, economic, ethical, and political insights. The complexity grows with the area, so that it is necessary to reduce the characteristic of the view in other ways, for example to a specific time of duration.

John Muir, Scots born early American conservationist,[11] wrote "When we try to pick out anything by itself we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe".

More information is to be found in the field of systems ecology, a cross-disciplinary field influenced by general systems theory.

Medicine

In primary care the term "holistic," has been used to describe approaches that take into account social considerations and other intuitive judgements.[12] The term holism, and so-called approaches, appear in psychosomatic medicine in the 1970s, when they were considered one possible way to conceptualize psychosomatic phenomena. Instead of charting one-way causal links from psyche to soma, or vice versa, it aimed at a systemic model, where multiple biological, psychological and social factors were seen as interlinked.[13]Other, alternative approaches in the 1970s were psychosomatic and somatopsychic approaches, which concentrated on causal links only from psyche to soma, or from soma to psyche, respectively.[13] At present it is commonplace in psychosomatic medicine to state that psyche and soma cannot really be separated for practical or theoretical purposes.[citation needed] A disturbance on any level—somatic, psychic, or social—will radiate to all the other levels, too. In this sense, psychosomatic thinking is similar to the biopsychosocial model of medicine.[citation needed]

Many alternative medicine practitioners claim a holistic approach to healing.

Neurology

A lively debate has run since the end of the 19th century regarding the functional organization of the brain. The holistic tradition (e.g., Pierre Marie) maintained that the brain was a homogeneous organ with no specific subparts whereas the localizationists (e.g., Paul Broca) argued that the brain was organized in functionally distinct cortical areas which were each specialized to process a given type of information or implement specific mental operations. The controversy was epitomized with the existence of a language area in the brain, nowadays known as the Broca's area.[14]Indications of holism in social science

Architecture

Architecture is often argued by design academics and those practicing in design to be a holistic enterprise.[15] Used in this context, holism tends to imply an all-inclusive design perspective. This trait is considered exclusive to architecture, distinct from other professions involved in design projects.Branding

A holistic brand (also holistic branding) is considering the entire brand or image of the company. For example, a universal brand image across all countries, including everything from advertising styles to the stationery the company has made, to the company colours.Economics

With roots in Schumpeter, the evolutionary approach might be considered the holist theory in economics. They share certain language from the biological evolutionary approach. They take into account how the innovation system evolves over time. Knowledge and know-how, know-who, know-what and know-why are part of the whole business economics. Knowledge can also be tacit, as described by Michael Polanyi. These models are open, and consider that it is hard to predict exactly the impact of a policy measure. They are also less mathematical.Education reform

The Taxonomy of Educational Objectives identifies many levels of cognitive functioning, which can be used to create a more holistic education. In authentic assessment, rather than using computers to score multiple choice tests, a standards based assessment uses trained scorers to score open-response items using holistic scoring methods.[16] In projects such as the North Carolina Writing Project, scorers are instructed not to count errors, or count numbers of points or supporting statements. The scorer is instead instructed to judge holistically whether "as a whole" is it more a "2" or a "3". Critics question whether such a process can be as objective as computer scoring, and the degree to which such scoring methods can result in different scores from different scorers.Psychology

Psychology of perception

A major holist movement in the early twentieth century was gestalt psychology. The claim was that perception is not an aggregation of atomic sense data but a field, in which there is a figure and a ground. Background has holistic effects on the perceived figure. Gestalt psychologists included Wolfgang Koehler, Max Wertheimer, Kurt Koffka. Koehler claimed the perceptual fields corresponded to electrical fields in the brain. Karl Lashley did experiments with gold foil pieces inserted in monkey brains purporting to show that such fields did not exist. However, many of the perceptual illusions and visual phenomena exhibited by the gestaltists were taken over (often without credit) by later perceptual psychologists. Gestalt psychology had influence on Fritz Perls' gestalt therapy, although some old-line gestaltists opposed the association with counter-cultural and New Age trends later associated with gestalt therapy. Gestalt theory was also influential on phenomenology. Aron Gurwitsch wrote on the role of the field of consciousness in gestalt theory in relation to phenomenology. Maurice Merleau-Ponty made much use of holistic psychologists such as work of Kurt Goldstein in his "Phenomenology of Perception."Teleological psychology

Alfred Adler believed that the individual (an integrated whole expressed through a self-consistent unity of thinking, feeling, and action, moving toward an unconscious, fictional final goal), must be understood within the larger wholes of society, from the groups to which he belongs (starting with his face-to-face relationships), to the larger whole of mankind. The recognition of our social embeddedness and the need for developing an interest in the welfare of others, as well as a respect for nature, is at the heart of Adler's philosophy of living and principles of psychotherapy.Edgar Morin, the French philosopher and sociologist, can be considered a holist based on the transdisciplinary nature of his work.

Mel Levine, M.D., author of A Mind at a Time,[17] and co-founder (with Charles R. Schwab) of the not-for-profit organization All Kinds of Minds, can be considered a holist based on his view of the 'whole child' as a product of many systems and his work supporting the educational needs of children through the management of a child's educational profile as a whole rather than isolated weaknesses in that profile.

Anthropology

There is an ongoing dispute as to whether anthropology is intrinsically holistic. Supporters of this concept consider anthropology holistic in two senses. First, it is concerned with all human beings across times and places, and with all dimensions of humanity (evolutionary, biophysical, sociopolitical, economic, cultural, psychological, etc.) Further, many academic programs following this approach take a "four-field" approach to anthropology that encompasses physical anthropology, archeology, linguistics, and cultural anthropology or social anthropology.[18]Some leading anthropologists disagree, and consider anthropological holism to be an artifact from 19th century social evolutionary thought that inappropriately imposes scientific positivism upon cultural anthropology.[19]

The term "holism" is additionally used within social and cultural anthropology to refer to an analysis of a society as a whole which refuses to break society into component parts. One definition says: "as a methodological ideal, holism implies ... that one does not permit oneself to believe that our own established institutional boundaries (e.g. between politics, sexuality, religion, economics) necessarily may be found also in foreign societies."[20]

Émile Durkheim

Émile Durkheim developed a concept of holism which he set as opposite to the notion that a society was nothing more than a simple collection of individuals. In more recent times, Louis Dumont[21] has contrasted "holism" to "individualism" as two different forms of societies. According to him, modern humans live in an individualist society, whereas ancient Greek society, for example, could be qualified as "holistic", because the individual found identity in the whole society. Thus, the individual was ready to sacrifice himself or herself for his or her community, as his or her life without the polis had no sense whatsoever.Cosmomorphism

The French Protestant missionary Maurice Leenhardt coined the term "cosmomorphism" to indicate the state of perfect symbiosis with the surrounding environment which characterized the culture of the Melanesians of New Caledonia. For these people, an isolated individual is totally indeterminate, indistinct, and featureless until he can find his position within the natural and social world in which he is inserted. The confines between the self and the world are annulled to the point that the material body itself is no guarantee of the sort of recognition of identity which is typical of our own culture.[22][23]Theology

Holistic concepts are strongly represented within the thoughts expressed within Logos (per Heraclitus), Panentheism and Pantheism.[citation needed]In theological anthropology, which belongs to theology and not to anthropology, holism is the belief that body, soul and spirit are not separate components of a person, but rather facets of a united whole.[24]