Human embryonic stem cells in cell culture

Pluripotent: Embryonic stem cells are able to develop into any type of

cell, excepting those of the placenta. Only embryonic stem cells of the morula are totipotent: able to develop into any type of cell, including those of the placenta.

Embryonic stem cells (ES cells or ESCs) are pluripotent stem cells derived from the inner cell mass of a blastocyst, an early-stage pre-implantation embryo.[1][2] Human embryos reach the blastocyst stage 4–5 days post fertilization, at which time they consist of 50–150 cells. Isolating the embryoblast, or inner cell mass (ICM) results in destruction of the blastocyst, a process which raises ethical issues, including whether or not embryos at the pre-implantation stage should be have the same moral considerations as embryos in the post-implantation stage of development.[3][4] Researchers are currently focusing heavily on the therapeutic potential of embryonic stem cells, with clinical use being the goal for many labs. These cells are being studied to be used as clinical therapies, models of genetic disorders, and cellular/DNA repair. However, adverse effects in the research and clinical processes have also been reported.

Properties

The transcriptome of embryonic stem cells

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs), derived from the blastocyst stage of early mammalian embryos, are distinguished by their ability to differentiate into any cell type and by their ability to propagate. It is these traits that makes them valuable in the scientific/medical fields. ESC are also described as having a normal karyotype, maintaining high telomerase activity, and exhibiting remarkable long-term proliferative potential.[5]

Pluripotent

Embryonic stem cells of the inner cell mass are pluripotent, meaning they are able to differentiate to generate primitive ectoderm, which ultimately differentiates during gastrulation into all derivatives of the three primary germ layers: ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm. These include each of the more than 220 cell types in the adult human body. Pluripotency distinguishes embryonic stem cells from adult stem cells, which are multipotent and can only produce a limited number of cell types.Propagation

Under defined conditions, embryonic stem cells are capable of propagating indefinitely in an undifferentiated state. Conditions must either prevent the cells from clumping, or maintain an environment that supports an unspecialized state.[2] While being able to remain undifferentiated, ESCs also have the capacity, when provided with the appropriate signals, to differentiate (presumably via the initial formation of precursor cells) into nearly all mature cell phenotypes.[6]Uses

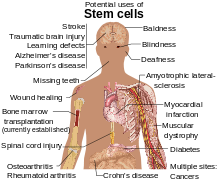

Due to their plasticity and potentially unlimited capacity for self-renewal, embryonic stem cell therapies have been proposed for regenerative medicine and tissue replacement after injury or disease. Pluripotent stem cells have shown potential in treating a number of varying conditions, including but not limited to: spinal cord injuries, age related macular degeneration, diabetes, neurodegenerative disorders (such as Parkinson's disease), AIDS, etc.[7] In addition to their potential in regenerative medicine, embryonic stem cells provide an alternative source of tissue/organs which serves as a possible solution to the donor shortage dilemma. Not only that, but tissue/organs derived from ESCs can be made immunocompatible with the recipient. Aside from these uses, embryonic stem cells can also serve as tools for the investigation of early human development, study of genetic disease and as in vitro systems for toxicology testing.[5]Utilizations

According to a 2002 article in PNAS, "Human embryonic stem cells have the potential to differentiate into various cell types, and, thus, may be useful as a source of cells for transplantation or tissue engineering."[8]

Embryoid bodies 24 hours after formation.

However, embryonic stem cells are not limited to cell/tissue engineering.

Cell Replacement Therapies

Current research focuses on differentiating ESCs into a variety of cell types for eventual use as cell replacement therapies (CRTs). Some of the cell types that have or are currently being developed include cardiomyocytes (CM), neurons, hepatocytes, bone marrow cells, islet cells and endothelial cells.[9] However, the derivation of such cell types from ESCs is not without obstacles, therefore current research is focused on overcoming these barriers. For example, studies are underway to differentiate ESCs in to tissue specific CMs and to eradicate their immature properties that distinguish them from adult CMs.[10]Clinical Potential

- Researchers have differentiated ESCs into dopamine-producing cells with the hope that these neurons could be used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease.[11][12]

- ESCs have been differentiated to natural killer (NK) cells and bone tissue.[13]

- Studies involving ESCs are underway to provide an alternative treatment for diabetes. For example, D’Amour et al. were able to differentiate ESCs into insulin producing cells[14] and researchers at Harvard University were able to produce large quantities of pancreatic beta cells from ES.[15]

- An article published in the European Heart Journal describes a translational process of generating human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiac progenitor cells to be used in clinical trials of patients with severe heart failure.[16]

Drug Discovery

Besides becoming an important alternative to organ transplants, ESCs are also being used in field of toxicology and as cellular screens to uncover new chemical entities (NCEs) that can be developed as small molecule drugs. Studies have shown that cardiomyocytes derived from ESCs are validated in vitro models to test drug responses and predict toxicity profiles.[9] ES derived cardiomyocytes have been shown to respond to pharmacological stimuli and hence can be used to assess cardiotoxicity like Torsades de Pointes.[17]ESC-derived hepatocytes are also useful models that could be used in the preclinical stages of drug discovery. However, the development of hepatocytes from ESCs has proven to be challenging and this hinders the ability to test drug metabolism. Therefore, current research is focusing on establishing fully functional ESC-derived hepatocytes with stable phase I and II enzyme activity.[18]

Models of Genetic Disorder

Several new studies have started to address the concept of modeling genetic disorders with embryonic stem cells. Either by genetically manipulating the cells, or more recently, by deriving diseased cell lines identified by prenatal genetic diagnosis (PGD), modeling genetic disorders is something that has been accomplished with stem cells. This approach may very well prove invaluable at studying disorders such as Fragile-X syndrome, Cystic fibrosis, and other genetic maladies that have no reliable model system.Yury Verlinsky, a Russian-American medical researcher who specialized in embryo and cellular genetics (genetic cytology), developed prenatal diagnosis testing methods to determine genetic and chromosomal disorders a month and a half earlier than standard amniocentesis. The techniques are now used by many pregnant women and prospective parents, especially couples who have a history of genetic abnormalities or where the woman is over the age of 35 (when the risk of genetically related disorders is higher). In addition, by allowing parents to select an embryo without genetic disorders, they have the potential of saving the lives of siblings that already had similar disorders and diseases using cells from the disease free offspring.[19]

Scientists have discovered a new technique for deriving human embryonic stem cell (ESC). Normal ESC lines from different sources of embryonic material including morula and whole blastocysts have been established. These findings allows researchers to construct ESC lines from embryos that acquire different genetic abnormalities; therefore, allowing for recognition of mechanisms in the molecular level that are possibly blocked that could impede the disease progression. The ESC lines originating from embryos with genetic and chromosomal abnormalities provide the data necessary to understand the pathways of genetic defects.[20]

A donor patient acquires one defective gene copy and one normal, and only one of these two copies is used for reproduction. By selecting egg cell derived from embryonic stem cells that have two normal copies, researchers can find variety of treatments for various diseases. To test this theory Dr. McLaughlin and several of his colleagues looked at whether parthenogenesis תשרקץצףפעסןembryonic stem cells can be used in a mouse model that has thalassemia intermedia. This disease is described as an inherited blood disorder in which there is a lack of hemoglobin leading to anemia. The mouse model used, had one defective gene copy. Embryonic stem cells from an unfertilized egg of the diseased mice were gathered and those stem cells that contained only healthy hemoglobin genes were identified. The healthy embryonic stem cell lines were then converted into cells transplanted into the carrier mice. After five weeks, the test results from the transplant illustrated that these carrier mice now had a normal blood cell count and hemoglobin levels.[21]

Repair of DNA damage

Differentiated somatic cells and ES cells use different strategies for dealing with DNA damage. For instance, human foreskin fibroblasts, one type of somatic cell, use non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), an error prone DNA repair process, as the primary pathway for repairing double-strand breaks (DSBs) during all cell cycle stages.[22] Because of its error-prone nature, NHEJ tends to produce mutations in a cell’s clonal descendants.ES cells use a different strategy to deal with DSBs.[23] Because ES cells give rise to all of the cell types of an organism including the cells of the germ line, mutations arising in ES cells due to faulty DNA repair are a more serious problem than in differentiated somatic cells. Consequently, robust mechanisms are needed in ES cells to repair DNA damages accurately, and if repair fails, to remove those cells with un-repaired DNA damages. Thus, mouse ES cells predominantly use high fidelity homologous recombinational repair (HRR) to repair DSBs.[23] This type of repair depends on the interaction of the two sister chromosomes formed during S phase and present together during the G2 phase of the cell cycle. HRR can accurately repair DSBs in one sister chromosome by using intact information from the other sister chromosome. Cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (i.e. after metaphase/cell division but prior the next round of replication) have only one copy of each chromosome (i.e. sister chromosomes aren’t present). Mouse ES cells lack a G1 checkpoint and do not undergo cell cycle arrest upon acquiring DNA damage.[24] Rather they undergo programmed cell death (apoptosis) in response to DNA damage.[25] Apoptosis can be used as a fail-safe strategy to remove cells with un-repaired DNA damages in order to avoid mutation and progression to cancer.[26] Consistent with this strategy, mouse ES stem cells have a mutation frequency about 100-fold lower than that of isogenic mouse somatic cells.[27]

Clinical trial

On January 23, 2009, Phase I clinical trials for transplantation of oligodendrocytes (a cell type of the brain and spinal cord) derived from human ES cells into spinal cord-injured individuals received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), marking it the world's first human ES cell human trial.[28] The study leading to this scientific advancement was conducted by Hans Keirstead and colleagues at the University of California, Irvine and supported by Geron Corporation of Menlo Park, CA, founded by Michael D. West, PhD. A previous experiment had shown an improvement in locomotor recovery in spinal cord-injured rats after a 7-day delayed transplantation of human ES cells that had been pushed into an oligodendrocytic lineage.[29] The phase I clinical study was designed to enroll about eight to ten paraplegics who have had their injuries no longer than two weeks before the trial begins, since the cells must be injected before scar tissue is able to form. The researchers emphasized that the injections were not expected to fully cure the patients and restore all mobility. Based on the results of the rodent trials, researchers speculated that restoration of myelin sheathes and an increase in mobility might occur. This first trial was primarily designed to test the safety of these procedures and if everything went well, it was hoped that it would lead to future studies that involve people with more severe disabilities.[30] The trial was put on hold in August 2009 due to FDA concerns regarding a small number of microscopic cysts found in several treated rat models but the hold was lifted on July 30, 2010.[31]In October 2010 researchers enrolled and administered ESTs to the first patient at Shepherd Center in Atlanta.[32] The makers of the stem cell therapy, Geron Corporation, estimated that it would take several months for the stem cells to replicate and for the GRNOPC1 therapy to be evaluated for success or failure.

In November 2011 Geron announced it was halting the trial and dropping out of stem cell research for financial reasons, but would continue to monitor existing patients, and was attempting to find a partner that could continue their research.[33] In 2013 BioTime (AMEX: BTX), led by CEO Dr. Michael D. West, acquired all of Geron's stem cell assets, with the stated intention of restarting Geron's embryonic stem cell-based clinical trial for spinal cord injury research.[34]

BioTime company Asterias Biotherapeutics (NYSE MKT: AST) was granted a $14.3 million Strategic Partnership Award by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) to re-initiate the world’s first embryonic stem cell-based human clinical trial, for spinal cord injury. Supported by California public funds, CIRM is the largest funder of stem cell-related research and development in the world.[35]

The award provides funding for Asterias to reinitiate clinical development of AST-OPC1 in subjects with spinal cord injury and to expand clinical testing of escalating doses in the target population intended for future pivotal trials.[35]

AST-OPC1 is a population of cells derived from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) that contains oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs). OPCs and their mature derivatives called oligodendrocytes provide critical functional support for nerve cells in the spinal cord and brain. Asterias recently presented the results from phase 1 clinical trial testing of a low dose of AST-OPC1 in patients with neurologically-complete thoracic spinal cord injury. The results showed that AST-OPC1 was successfully delivered to the injured spinal cord site. Patients followed 2–3 years after AST-OPC1 administration showed no evidence of serious adverse events associated with the cells in detailed follow-up assessments including frequent neurological exams and MRIs. Immune monitoring of subjects through one year post-transplantation showed no evidence of antibody-based or cellular immune responses to AST-OPC1. In four of the five subjects, serial MRI scans performed throughout the 2–3 year follow-up period indicate that reduced spinal cord cavitation may have occurred and that AST-OPC1 may have had some positive effects in reducing spinal cord tissue deterioration. There was no unexpected neurological degeneration or improvement in the five subjects in the trial as evaluated by the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) exam.[35]

The Strategic Partnership III grant from CIRM will provide funding to Asterias to support the next clinical trial of AST-OPC1 in subjects with spinal cord injury, and for Asterias’ product development efforts to refine and scale manufacturing methods to support later-stage trials and eventually commercialization. CIRM funding will be conditional on FDA approval for the trial, completion of a definitive agreement between Asterias and CIRM, and Asterias’ continued progress toward the achievement of certain pre-defined project milestones.[35]

Adverse effect

The major concern with the possible transplantation of ESC into patients as therapies is their ability to form tumors including teratoma.[36] Safety issues prompted the FDA to place a hold on the first ESC clinical trial (see below), however no tumors were observed.The main strategy to enhance the safety of ESC for potential clinical use is to differentiate the ESC into specific cell types (e.g. neurons, muscle, liver cells) that have reduced or eliminated ability to cause tumors. Following differentiation, the cells are subjected to sorting by flow cytometry for further purification. ESC are predicted to be inherently safer than IPS cells because they are not genetically modified with genes such as c-Myc that are linked to cancer. Nonetheless, ESC express very high levels of the iPS inducing genes and these genes including Myc are essential for ESC self-renewal and pluripotency,[37] and potential strategies to improve safety by eliminating c-Myc expression are unlikely to preserve the cells' "stemness". However, N-myc and L-myc have been identified to induce iPS cells instead of c-myc with similar efficiency.[38]

History

- 1964: Lewis Kleinsmith and G. Barry Pierce Jr. isolated a single type of cell from a teratocarcinoma, a tumor now known to be derived from a germ cell.[39] These cells isolated from the teratocarcinoma replicated and grew in cell culture as a stem cell and are now known as embryonal carcinoma (EC) cells.[40] Although similarities in morphology and differentiating potential (pluripotency) led to the use of EC cells as the in vitro model for early mouse development,[41] EC cells harbor genetic mutations and often abnormal karyotypes that accumulated during the development of the teratocarcinoma. These genetic aberrations further emphasized the need to be able to culture pluripotent cells directly from the inner cell mass.

Martin Evans revealed a new technique for culturing the mouse embryos in

the uterus to allow for the derivation of ES cells from these embryos.

- 1981: Embryonic stem cells (ES cells) were independently first derived from mouse embryos by two groups. Martin Evans and Matthew Kaufman from the Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge published first in July, revealing a new technique for culturing the mouse embryos in the uterus to allow for an increase in cell number, allowing for the derivation of ES cells from these embryos.[42] Gail R. Martin, from the Department of Anatomy, University of California, San Francisco, published her paper in December and coined the term “Embryonic Stem Cell”.[43] She showed that embryos could be cultured in vitro and that ES cells could be derived from these embryos. In 1998, a breakthrough occurred when researchers, led by James Thomson at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, first developed a technique to isolate and grow human embryonic stem cells in cell culture.[44]

- 1989: Mario R. Cappechi, Martin J. Evans, and Oliver Smithies publish their research which details their isolation and genetic modifications of embryonic stem cells, creating the first "knockout mice". [45] In creating knockout mice, this publication provided scientists with an entirely new way to study disease.

- 1998: A paper titled "Embryonic Stem Cell Lines Derived From Human Blastocysts" is published by a team from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. The researchers behind this study not only create the first embryonic stem cells, but recognize their pluripotency, as well as their capacity for self-renewal. The abstract of the paper notes the significance of the discovery with regards to the fields of developmental biology and drug discovery. [46]

Techniques and conditions for derivation and culture

Derivation from humans

In vitro fertilization generates multiple embryos. The surplus of embryos is not clinically used or is unsuitable for implantation into the patient, and therefore may be donated by the donor with consent. Human embryonic stem cells can be derived from these donated embryos or additionally they can also be extracted from cloned embryos using a cell from a patient and a donated egg.[47] The inner cell mass (cells of interest), from the blastocyst stage of the embryo, is separated from the trophectoderm, the cells that would differentiate into extra-embryonic tissue. Immunosurgery, the process in which antibodies are bound to the trophectoderm and removed by another solution, and mechanical dissection are performed to achieve separation. The resulting inner cell mass cells are plated onto cells that will supply support. The inner cell mass cells attach and expand further to form a human embryonic cell line, which are undifferentiated. These cells are fed daily and are enzymatically or mechanically separated every four to seven days. For differentiation to occur, the human embryonic stem cell line is removed from the supporting cells to form embryoid bodies, is co-cultured with a serum containing necessary signals, or is grafted in a three-dimensional scaffold to result.[48]Derivation from other animals

Embryonic stem cells are derived from the inner cell mass of the early embryo, which are harvested from the donor mother animal. Martin Evans and Matthew Kaufman reported a technique that delays embryo implantation, allowing the inner cell mass to increase. This process includes removing the donor mother's ovaries and dosing her with progesterone, changing the hormone environment, which causes the embryos to remain free in the uterus. After 4–6 days of this intrauterine culture, the embryos are harvested and grown in in vitro culture until the inner cell mass forms “egg cylinder-like structures,” which are dissociated into single cells, and plated on fibroblasts treated with mitomycin-c (to prevent fibroblast mitosis). Clonal cell lines are created by growing up a single cell. Evans and Kaufman showed that the cells grown out from these cultures could form teratomas and embryoid bodies, and differentiate in vitro, all of which indicating that the cells are pluripotent.[42]Gail Martin derived and cultured her ES cells differently. She removed the embryos from the donor mother at approximately 76 hours after copulation and cultured them overnight in a medium containing serum. The following day, she removed the inner cell mass from the late blastocyst using microsurgery. The extracted inner cell mass was cultured on fibroblasts treated with mitomycin-c in a medium containing serum and conditioned by ES cells. After approximately one week, colonies of cells grew out. These cells grew in culture and demonstrated pluripotent characteristics, as demonstrated by the ability to form teratomas, differentiate in vitro, and form embryoid bodies. Martin referred to these cells as ES cells.[43]

It is now known that the feeder cells provide leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and serum provides bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) that are necessary to prevent ES cells from differentiating.[49][50] These factors are extremely important for the efficiency of deriving ES cells. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that different mouse strains have different efficiencies for isolating ES cells.[51] Current uses for mouse ES cells include the generation of transgenic mice, including knockout mice. For human treatment, there is a need for patient specific pluripotent cells. Generation of human ES cells is more difficult and faces ethical issues. So, in addition to human ES cell research, many groups are focused on the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells).[52]

Potential method for new cell line derivation

On August 23, 2006, the online edition of Nature scientific journal published a letter by Dr. Robert Lanza (medical director of Advanced Cell Technology in Worcester, MA) stating that his team had found a way to extract embryonic stem cells without destroying the actual embryo.[53] This technical achievement would potentially enable scientists to work with new lines of embryonic stem cells derived using public funding in the USA, where federal funding was at the time limited to research using embryonic stem cell lines derived prior to August 2001. In March, 2009, the limitation was lifted.[54]Induced pluripotent stem cells

The iPSC technology was pioneered by Shinya Yamanaka’s lab in Kyoto, Japan, who showed in 2006 that the introduction of four specific genes encoding transcription factors could convert adult cells into pluripotent stem cells.[55] He was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize along with Sir John Gurdon "for the discovery that mature cells can be reprogrammed to become pluripotent." [56]In 2007 it was shown that pluripotent stem cells highly similar to embryonic stem cells can be generated by the delivery of three genes (Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4) to differentiated cells.[57] The delivery of these genes "reprograms" differentiated cells into pluripotent stem cells, allowing for the generation of pluripotent stem cells without the embryo. Because ethical concerns regarding embryonic stem cells typically are about their derivation from terminated embryos, it is believed that reprogramming to these "induced pluripotent stem cells" (iPS cells) may be less controversial. Both human and mouse cells can be reprogrammed by this methodology, generating both human pluripotent stem cells and mouse pluripotent stem cells without an embryo.[58]

This may enable the generation of patient specific ES cell lines that could potentially be used for cell replacement therapies. In addition, this will allow the generation of ES cell lines from patients with a variety of genetic diseases and will provide invaluable models to study those diseases.

However, as a first indication that the induced pluripotent stem cell (iPS) cell technology can in rapid succession lead to new cures, it was used by a research team headed by Rudolf Jaenisch of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to cure mice of sickle cell anemia, as reported by Science journal's online edition on December 6, 2007.[59][60]

On January 16, 2008, a California-based company, Stemagen, announced that they had created the first mature cloned human embryos from single skin cells taken from adults. These embryos can be harvested for patient matching embryonic stem cells.[61]

Contamination by reagents used in cell culture

The online edition of Nature Medicine published a study on January 24, 2005, which stated that the human embryonic stem cells available for federally funded research are contaminated with non-human molecules from the culture medium used to grow the cells.[62] It is a common technique to use mouse cells and other animal cells to maintain the pluripotency of actively dividing stem cells. The problem was discovered when non-human sialic acid in the growth medium was found to compromise the potential uses of the embryonic stem cells in humans, according to scientists at the University of California, San Diego.[63]However, a study published in the online edition of Lancet Medical Journal on March 8, 2005 detailed information about a new stem cell line that was derived from human embryos under completely cell- and serum-free conditions. After more than 6 months of undifferentiated proliferation, these cells demonstrated the potential to form derivatives of all three embryonic germ layers both in vitro and in teratomas. These properties were also successfully maintained (for more than 30 passages) with the established stem cell lines.[64]