Some major international efforts to search for extraterrestrial life. Clockwise from top left:

- The search for extrasolar planets (image: Kepler telescope)

- Listening for extraterrestrial signals indicating intelligence (image: Allen array)

- Robotic exploration of the Solar System (image: Curiosity rover on Mars)

Since the mid-20th century, there has been an ongoing search for signs of extraterrestrial life. This encompasses a search for current and historic extraterrestrial life, and a narrower search for extraterrestrial intelligent life. Depending on the category of search, methods range from the analysis of telescope and specimen data[3] to radios used to detect and send communication signals.

The concept of extraterrestrial life, and particularly extraterrestrial intelligence, has had a major cultural impact, chiefly in works of science fiction. Over the years, science fiction communicated scientific ideas, imagined a wide range of possibilities, and influenced public interest in and perspectives of extraterrestrial life. One shared space is the debate over the wisdom of attempting communication with extraterrestrial intelligence. Some encourage aggressive methods to try for contact with intelligent extraterrestrial life. Others—citing the tendency of technologically advanced human societies to enslave or wipe out less advanced societies—argue that it may be dangerous to actively call attention to Earth.[4][5]

General

Alien life, such as microorganisms, has been hypothesized to exist in the Solar System and throughout the universe. This hypothesis relies on the vast size and consistent physical laws of the observable universe. According to this argument, made by scientists such as Carl Sagan and Stephen Hawking,[6] as well as well-regarded thinkers such as Winston Churchill,[7][8] it would be improbable for life not to exist somewhere other than Earth.[9][10] This argument is embodied in the Copernican principle, which states that Earth does not occupy a unique position in the Universe, and the mediocrity principle, which states that there is nothing special about life on Earth.[11] The chemistry of life may have begun shortly after the Big Bang, 13.8 billion years ago, during a habitable epoch when the universe was only 10–17 million years old.[12][13] Life may have emerged independently at many places throughout the universe. Alternatively, life may have formed less frequently, then spread—by meteoroids, for example—between habitable planets in a process called panspermia.[14][15] In any case, complex organic molecules may have formed in the protoplanetary disk of dust grains surrounding the Sun before the formation of Earth.[16] According to these studies, this process may occur outside Earth on several planets and moons of the Solar System and on planets of other stars.[16]Since the 1950s, scientists have proposed that "habitable zones" around stars are the most likely places to find life. Numerous discoveries in such zones since 2007 have generated numerical estimates of Earth-like planets —in terms of composition—of many billions.[17] As of 2013, only a few planets have been discovered in these zones.[18] Nonetheless, on 4 November 2013, astronomers reported, based on Kepler space mission data, that there could be as many as 40 billion Earth-sized planets orbiting in the habitable zones of Sun-like stars and red dwarfs in the Milky Way,[19][20] 11 billion of which may be orbiting Sun-like stars.[21] The nearest such planet may be 12 light-years away, according to the scientists.[19][20] Astrobiologists have also considered a "follow the energy" view of potential habitats.[22][23]

Evolution

A study published in 2017 suggests that due to how complexity evolved in species on Earth, the level of predictability for alien evolution elsewhere would make them look similar to life on our planet. One of the study authors, Sam Levin, notes "Like humans, we predict that they are made-up of a hierarchy of entities, which all cooperate to produce an alien. At each level of the organism there will be mechanisms in place to eliminate conflict, maintain cooperation, and keep the organism functioning. We can even offer some examples of what these mechanisms will be."[24] There is also research in assessing the capacity of life for developing intelligence. It has been suggested that this capacity arises with the number of potential niches a planet contains, and that the complexity of life itself is reflected in the information density of planetary environments, which in turn can be computed from its niches.[25]Biochemical basis

Life on Earth requires water as a solvent in which biochemical reactions take place. Sufficient quantities of carbon and other elements, along with water, might enable the formation of living organisms on terrestrial planets with a chemical make-up and temperature range similar to that of Earth.[26][27] More generally, life based on ammonia (rather than water) has been suggested, though this solvent appears less suitable than water. It is also conceivable that there are forms of life whose solvent is a liquid hydrocarbon, such as methane, ethane or propane.[28]About 29 chemical elements play an active positive role in living organisms on Earth.[29] About 95% of living matter is built upon only six elements: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and sulfur. These six elements form the basic building blocks of virtually all life on Earth, whereas most of the remaining elements are found only in trace amounts.[30] The unique characteristics of carbon make it unlikely that it could be replaced, even on another planet, to generate the biochemistry necessary for life. The carbon atom has the unique ability to make four strong chemical bonds with other atoms, including other carbon atoms. These covalent bonds have a direction in space, so that carbon atoms can form the skeletons of complex 3-dimensional structures with definite architectures such as nucleic acids and proteins. Carbon forms more compounds than all other elements combined. The great versatility of the carbon atom makes it the element most likely to provide the bases—even exotic ones—for the chemical composition of life on other planets.[31]

Planetary habitability in the Solar System

Some bodies in the Solar System have the potential for an environment in which extraterrestrial life can exist, particularly those with possible subsurface oceans.[32] Should life be discovered elsewhere in the Solar System, astrobiologists suggest that it will more likely be in the form of extremophile microorganisms. According to NASA's 2015 Astrobiology Strategy, "Life on other worlds is most likely to include microbes, and any complex living system elsewhere is likely to have arisen from and be founded upon microbial life. Important insights on the limits of microbial life can be gleaned from studies of microbes on modern Earth, as well as their ubiquity and ancestral characteristics."[33] Mars may have niche subsurface environments where microbial life might exist.[34][35][36] A subsurface marine environment on Jupiter's moon Europa might be the most likely habitat in the Solar System, outside Earth, for extremophile microorganisms.[37][38][39]The panspermia hypothesis proposes that life elsewhere in the Solar System may have a common origin. If extraterrestrial life was found on another body in the Solar System, it could have originated from Earth just as life on Earth could have been seeded from elsewhere (exogenesis). The first known mention of the term 'panspermia' was in the writings of the 5th century BC Greek philosopher Anaxagoras.[40] In the 19th century it was again revived in modern form by several scientists, including Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1834),[41] Kelvin (1871),[42] Hermann von Helmholtz (1879)[43] and, somewhat later, by Svante Arrhenius (1903).[44] Sir Fred Hoyle (1915–2001) and Chandra Wickramasinghe (born 1939) are important proponents of the hypothesis who further contended that life forms continue to enter Earth's atmosphere, and may be responsible for epidemic outbreaks, new diseases, and the genetic novelty necessary for macroevolution.[45]

Directed panspermia concerns the deliberate transport of microorganisms in space, sent to Earth to start life here, or sent from Earth to seed new stellar systems with life. The Nobel prize winner Francis Crick, along with Leslie Orgel proposed that seeds of life may have been purposely spread by an advanced extraterrestrial civilization,[46] but considering an early "RNA world" Crick noted later that life may have originated on Earth.[47]

Venus

In the early 20th century, Venus was often thought to be similar to Earth in terms of habitability, but observations since the beginning of the Space Age have revealed that Venus's surface is inhospitable to Earth-like life. However, between an altitude of 50 and 65 kilometers, the pressure and temperature are Earth-like, and it has been speculated that thermoacidophilic extremophile microorganisms might exist in the acidic upper layers of the Venusian atmosphere.[48][49][50][51] Furthermore, Venus likely had liquid water on its surface for at least a few million years after its formation.[52][53][54]Mars

Life on Mars has been long speculated. Liquid water is widely thought to have existed on Mars in the past, and now can occasionally be found as low-volume liquid brines in shallow Martian soil.[55] The origin of the potential biosignature of methane observed in Mars' atmosphere is unexplained, although hypotheses not involving life have also been proposed.[56]There is evidence that Mars had a warmer and wetter past: dried-up river beds, polar ice caps, volcanoes, and minerals that form in the presence of water have all been found. Nevertheless, present conditions on Mars' subsurface may support life.[57][58] Evidence obtained by the Curiosity rover studying Aeolis Palus, Gale Crater in 2013 strongly suggests an ancient freshwater lake that could have been a hospitable environment for microbial life.[59][60]

Current studies on Mars by the Curiosity and Opportunity rovers are searching for evidence of ancient life, including a biosphere based on autotrophic, chemotrophic and/or chemolithoautotrophic microorganisms, as well as ancient water, including fluvio-lacustrine environments (plains related to ancient rivers or lakes) that may have been habitable.[61][62][63][64] The search for evidence of habitability, taphonomy (related to fossils), and organic carbon on Mars is now a primary NASA objective.[61]

Ceres

Ceres, the only dwarf planet in the asteroid belt, has a thin water-vapor atmosphere.[65][66] Frost on the surface may also have been detected in the form of bright spots.[67][68][69] The presence of water on Ceres has led to speculation that life may be possible there.[70][71][72]Jupiter system

Jupiter

Carl Sagan and others in the 1960s and 1970s computed conditions for hypothetical microorganisms living in the atmosphere of Jupiter.[73] The intense radiation and other conditions, however, do not appear to permit encapsulation and molecular biochemistry, so life there is thought unlikely.[74] In contrast, some of Jupiter's moons may have habitats capable of sustaining life. Scientists have indications that heated subsurface oceans of liquid water may exist deep under the crusts of the three outer Galilean moons—Europa,[37][38][75] Ganymede,[76][77][78][79][80] and Callisto.[81][82][83] The EJSM/Laplace mission is planned to determine the habitability of these environments.Europa

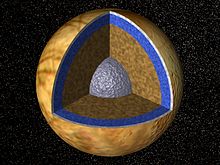

Internal structure of Europa. The blue is a subsurface ocean. Such subsurface oceans could possibly harbor life.[84]

Jupiter's moon Europa has been subject to speculation about the existence of life due to the strong possibility of a liquid water ocean beneath its ice surface.[37][39] Hydrothermal vents on the bottom of the ocean, if they exist, may warm the ice and could be capable of supporting multicellular microorganisms.[85] It is also possible that Europa could support aerobic macrofauna using oxygen created by cosmic rays impacting its surface ice.[86]

The case for life on Europa was greatly enhanced in 2011 when it was discovered that vast lakes exist within Europa's thick, icy shell. Scientists found that ice shelves surrounding the lakes appear to be collapsing into them, thereby providing a mechanism through which life-forming chemicals created in sunlit areas on Europa's surface could be transferred to its interior.[87][88]

On 11 December 2013, NASA reported the detection of "clay-like minerals" (specifically, phyllosilicates), often associated with organic materials, on the icy crust of Europa.[89] The presence of the minerals may have been the result of a collision with an asteroid or comet according to the scientists.[89] The Europa Clipper, which would assess the habitability of Europa, is planned for launch in 2025.[90][91] Europa's subsurface ocean is considered the best target for the discovery of life.[37][39]

Saturn system

Titan and Enceladus have been speculated to have possible habitats supportive of life.Enceladus

Enceladus, a moon of Saturn, has some of the conditions for life, including geothermal activity and water vapor, as well as possible under-ice oceans heated by tidal effects.[92][93] The Cassini–Huygens probe detected carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and oxygen—all key elements for supporting life—during its 2005 flyby through one of Enceladus's geysers spewing ice and gas. The temperature and density of the plumes indicate a warmer, watery source beneath the surface.[56]Titan

Titan, the largest moon of Saturn, is the only known moon in the Solar System with a significant atmosphere. Data from the Cassini–Huygens mission refuted the hypothesis of a global hydrocarbon ocean, but later demonstrated the existence of liquid hydrocarbon lakes in the polar regions—the first stable bodies of surface liquid discovered outside Earth.[94][95][96] Analysis of data from the mission has uncovered aspects of atmospheric chemistry near the surface that are consistent with—but do not prove—the hypothesis that organisms there if present, could be consuming hydrogen, acetylene and ethane, and producing methane.[97][98][99]Small Solar System bodies

Small Solar System bodies have also been speculated to host habitats for extremophiles. Fred Hoyle and Chandra Wickramasinghe have proposed that microbial life might exist on comets and asteroids.Other bodies

Models of heat retention and heating via radioactive decay in smaller icy Solar System bodies suggest that Rhea, Titania, Oberon, Triton, Pluto, Eris, Sedna, and Orcus may have oceans underneath solid icy crusts approximately 100 km thick.[104] Of particular interest in these cases is the fact that the models indicate that the liquid layers are in direct contact with the rocky core, which allows efficient mixing of minerals and salts into the water. This is in contrast with the oceans that may be inside larger icy satellites like Ganymede, Callisto, or Titan, where layers of high-pressure phases of ice are thought to underlie the liquid water layer.[104]Hydrogen sulfide has been proposed as a hypothetical solvent for life and is quite plentiful on Jupiter's moon Io, and may be in liquid form a short distance below the surface.[105]

Scientific search

The scientific search for extraterrestrial life is being carried out both directly and indirectly. As of September 2017, 3,667 exoplanets in 2,747 systems have been identified, and other planets and moons in our own solar system hold the potential for hosting primitive life such as microorganisms.Direct search

Scientists search for biosignatures within the Solar System by studying planetary surfaces and examining meteorites.[12][13] Some claim to have identified evidence that microbial life has existed on Mars.[106][107][108][109][110][111] An experiment on the two Viking Mars landers reported gas emissions from heated Martian soil samples that some scientists argue are consistent with the presence of living microorganisms.[112] Lack of corroborating evidence from other experiments on the same samples, suggests that a non-biological reaction is a more likely hypothesis. In 1996, a controversial report stated that structures resembling nanobacteria were discovered in a meteorite, ALH84001, formed of rock ejected from Mars.[106][107]

Electron micrograph of martian meteorite ALH84001 showing structures that some scientists think could be fossilized bacteria-like life forms.

In February 2005, NASA scientists reported that they may have found some evidence of present life on Mars.[118] The two scientists, Carol Stoker and Larry Lemke of NASA's Ames Research Center, based their claim on methane signatures found in Mars's atmosphere resembling the methane production of some forms of primitive life on Earth, as well as on their own study of primitive life near the Rio Tinto river in Spain. NASA officials soon distanced NASA from the scientists' claims, and Stoker herself backed off from her initial assertions.[119] Though such methane findings are still debated, support among some scientists for the existence of life on Mars exists.[120]

In November 2011, NASA launched the Mars Science Laboratory that landed the Curiosity rover on Mars. It is designed to assess the past and present habitability on Mars using a variety of scientific instruments. The rover landed on Mars at Gale Crater in August 2012.[121][122]

The Gaia hypothesis stipulates that any planet with a robust population of life will have an atmosphere in chemical disequilibrium, which is relatively easy to determine from a distance by spectroscopy. However, significant advances in the ability to find and resolve light from smaller rocky worlds near their star are necessary before such spectroscopic methods can be used to analyze extrasolar planets. To that effect, the Carl Sagan Institute was founded in 2014 and is dedicated to the atmospheric characterization of exoplanets in circumstellar habitable zones.[123][124] Planetary spectroscopic data will be obtained from telescopes like WFIRST and ELT.[125]

In August 2011, findings by NASA, based on studies of meteorites found on Earth, suggest DNA and RNA components (adenine, guanine and related organic molecules), building blocks for life as we know it, may be formed extraterrestrially in outer space.[126][127][128] In October 2011, scientists reported that cosmic dust contains complex organic matter ("amorphous organic solids with a mixed aromatic-aliphatic structure") that could be created naturally, and rapidly, by stars.[129][130][131] One of the scientists suggested that these compounds may have been related to the development of life on Earth and said that, "If this is the case, life on Earth may have had an easier time getting started as these organics can serve as basic ingredients for life."[129]

In August 2012, and in a world first, astronomers at Copenhagen University reported the detection of a specific sugar molecule, glycolaldehyde, in a distant star system. The molecule was found around the protostellar binary IRAS 16293-2422, which is located 400 light years from Earth.[132][133] Glycolaldehyde is needed to form ribonucleic acid, or RNA, which is similar in function to DNA. This finding suggests that complex organic molecules may form in stellar systems prior to the formation of planets, eventually arriving on young planets early in their formation.[134]

Indirect search

Projects such as SETI are monitoring the galaxy for electromagnetic interstellar communications from civilizations on other worlds.[135][136] If there is an advanced extraterrestrial civilization, there is no guarantee that it is transmitting radio communications in the direction of Earth or that this information could be interpreted as such by humans. The length of time required for a signal to travel across the vastness of space means that any signal detected would come from the distant past.[137]The presence of heavy elements in a star's light-spectrum is another potential biosignature; such elements would (in theory) be found if the star was being used as an incinerator/repository for nuclear waste products.[138]

Extrasolar planets

Artist's Impression of Gliese 581 c, the first terrestrial extrasolar planet discovered within its star's habitable zone.

Artist's impression of the Kepler telescope in space.

Some astronomers search for extrasolar planets that may be conducive to life, narrowing the search to terrestrial planets within the habitable zone of their star.[139][140] Since 1992 over two thousand exoplanets have been discovered (3,815 planets in 2,853 planetary systems including 633 multiple planetary systems as of 1 August 2018).[141] The extrasolar planets so far discovered range in size from that of terrestrial planets similar to Earth's size to that of gas giants larger than Jupiter.[141] The number of observed exoplanets is expected to increase greatly in the coming years.[142]

The Kepler space telescope has also detected a few thousand[143][144] candidate planets,[145][146] of which about 11% may be false positives.[147]

There is at least one planet on average per star.[148] About 1 in 5 Sun-like stars[a] have an "Earth-sized"[b] planet in the habitable zone,[c] with the nearest expected to be within 12 light-years distance from Earth.[149][150] Assuming 200 billion stars in the Milky Way,[d] that would be 11 billion potentially habitable Earth-sized planets in the Milky Way, rising to 40 billion if red dwarfs are included.[21] The rogue planets in the Milky Way possibly number in the trillions.[151]

The nearest known exoplanet is Proxima Centauri b, located 4.2 light-years (1.3 pc) from Earth in the southern constellation of Centaurus.[152]

As of March 2014, the least massive planet known is PSR B1257+12 A, which is about twice the mass of the Moon. The most massive planet listed on the NASA Exoplanet Archive is DENIS-P J082303.1-491201 b,[153][154] about 29 times the mass of Jupiter, although according to most definitions of a planet, it is too massive to be a planet and may be a brown dwarf instead. Almost all of the planets detected so far are within the Milky Way, but there have also been a few possible detections of extragalactic planets. The study of planetary habitability also considers a wide range of other factors in determining the suitability of a planet for hosting life.[3]

One sign that a planet probably already contains life is the presence of an atmosphere with significant amounts of oxygen, since that gas is highly reactive and generally would not last long without constant replenishment. This replenishment occurs on Earth through photosynthetic organisms. One way to analyze the atmosphere of an exoplanet is through spectrography when it transits its star, though this might only be feasible with dim stars like white dwarfs.[155]

Terrestrial analysis

The science of astrobiology considers life on Earth as well, and in the broader astronomical context. In 2015, "remains of biotic life" were found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia, when the young Earth was about 400 million years old.[156][157] According to one of the researchers, "If life arose relatively quickly on Earth, then it could be common in the universe."[156]The Drake equation

In 1961, University of California, Santa Cruz, astronomer and astrophysicist Frank Drake devised the Drake equation as a way to stimulate scientific dialogue at a meeting on the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI).[158] The Drake equation is a probabilistic argument used to estimate the number of active, communicative extraterrestrial civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy. The equation is best understood not as an equation in the strictly mathematical sense, but to summarize all the various concepts which scientists must contemplate when considering the question of life elsewhere.[159] The Drake equation is:- N = the number of Milky Way galaxy civilizations already capable of communicating across interplanetary space

- R* = the average rate of star formation in our galaxy

- fp = the fraction of those stars that have planets

- ne = the average number of planets that can potentially support life

- fl = the fraction of planets that actually support life

- fi = the fraction of planets with life that evolves to become intelligent life (civilizations)

- fc = the fraction of civilizations that develop a technology to broadcast detectable signs of their existence into space

- L = the length of time over which such civilizations broadcast detectable signals into space

The Drake equation has proved controversial since several of its factors are uncertain and based on conjecture, not allowing conclusions to be made.[161] This has led critics to label the equation a guesstimate, or even meaningless.

Based on observations from the Hubble Space Telescope, there are between 125 and 250 billion galaxies in the observable universe.[162] It is estimated that at least ten percent of all Sun-like stars have a system of planets,[163] i.e. there are 6.25×1018 stars with planets orbiting them in the observable universe. Even if it is assumed that only one out of a billion of these stars has planets supporting life, there would be some 6.25 billion life-supporting planetary systems in the observable universe.

A 2013 study based on results from the Kepler spacecraft estimated that the Milky Way contains at least as many planets as it does stars, resulting in 100–400 billion exoplanets.[164][165] Also based on Kepler data, scientists estimate that at least one in six stars has an Earth-sized planet.[166]

The apparent contradiction between high estimates of the probability of the existence of extraterrestrial civilizations and the lack of evidence for such civilizations is known as the Fermi paradox.[167]

Cultural impact

Cosmic pluralism

Cosmic pluralism, the plurality of worlds, or simply pluralism, describes the philosophical belief in numerous "worlds" in addition to Earth, which might harbor extraterrestrial life. Before the development of the heliocentric theory and a recognition that the Sun is just one of many stars,[168] the notion of pluralism was largely mythological and philosophical.[169][170][171] Medieval Muslim writers like Fakhr al-Din al-Razi and Muhammad al-Baqir supported cosmic pluralism on the basis of the Qur'an.[172]With the scientific and Copernican revolutions, and later, during the Enlightenment, cosmic pluralism became a mainstream notion, supported by the likes of Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle in his 1686 work Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes.[173] Pluralism was also championed by philosophers such as John Locke, Giordano Bruno and astronomers such as William Herschel. The astronomer Camille Flammarion promoted the notion of cosmic pluralism in his 1862 book La pluralité des mondes habités.[174] None of these notions of pluralism were based on any specific observation or scientific information.

Early modern period

There was a dramatic shift in thinking initiated by the invention of the telescope and the Copernican assault on geocentric cosmology. Once it became clear that Earth was merely one planet amongst countless bodies in the universe, the theory of extraterrestrial life started to become a topic in the scientific community. The best known early-modern proponent of such ideas was the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno, who argued in the 16th century for an infinite universe in which every star is surrounded by its own planetary system. Bruno wrote that other worlds "have no less virtue nor a nature different to that of our earth" and, like Earth, "contain animals and inhabitants".[175]In the early 17th century, the Czech astronomer Anton Maria Schyrleus of Rheita mused that "if Jupiter has (...) inhabitants (...) they must be larger and more beautiful than the inhabitants of Earth, in proportion to the [characteristics] of the two spheres".[176]

In Baroque literature such as The Other World: The Societies and Governments of the Moon by Cyrano de Bergerac, extraterrestrial societies are presented as humoristic or ironic parodies of earthly society. The didactic poet Henry More took up the classical theme of the Greek Democritus in "Democritus Platonissans, or an Essay Upon the Infinity of Worlds" (1647). In "The Creation: a Philosophical Poem in Seven Books" (1712), Sir Richard Blackmore observed: "We may pronounce each orb sustains a race / Of living things adapted to the place". With the new relative viewpoint that the Copernican revolution had wrought, he suggested "our world's sunne / Becomes a starre elsewhere". Fontanelle's "Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds" (translated into English in 1686) offered similar excursions on the possibility of extraterrestrial life, expanding, rather than denying, the creative sphere of a Maker.

The possibility of extraterrestrials remained a widespread speculation as scientific discovery accelerated. William Herschel, the discoverer of Uranus, was one of many 18th–19th-century astronomers who believed that the Solar System is populated by alien life. Other luminaries of the period who championed "cosmic pluralism" included Immanuel Kant and Benjamin Franklin. At the height of the Enlightenment, even the Sun and Moon were considered candidates for extraterrestrial inhabitants.

19th century

Artificial Martian channels, depicted by Percival Lowell

Speculation about life on Mars increased in the late 19th century, following telescopic observation of apparent Martian canals—which soon, however, turned out to be optical illusions.[177] Despite this, in 1895, American astronomer Percival Lowell published his book Mars, followed by Mars and its Canals in 1906, proposing that the canals were the work of a long-gone civilization.[178] The idea of life on Mars led British writer H. G. Wells to write the novel The War of the Worlds in 1897, telling of an invasion by aliens from Mars who were fleeing the planet's desiccation.

Spectroscopic analysis of Mars's atmosphere began in earnest in 1894, when U.S. astronomer William Wallace Campbell showed that neither water nor oxygen was present in the Martian atmosphere.[179] By 1909 better telescopes and the best perihelic opposition of Mars since 1877 conclusively put an end to the canal hypothesis.

The science fiction genre, although not so named during the time, developed during the late 19th century. Jules Verne's Around the Moon (1870) features a discussion of the possibility of life on the Moon, but with the conclusion that it is barren. Stories involving extraterrestrials are found in e.g. Garrett P. Serviss's Edison's Conquest of Mars (1898), an unauthorized sequel to The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells was published in 1897 which stands at the beginning of the popular idea of the "Martian invasion" of Earth prominent in 20th-century pop culture.

20th century

The Arecibo message is a digital message sent to Messier 13, and is a well-known symbol of human attempts to contact extraterrestrials.

Most unidentified flying objects or UFO sightings[180] can be readily explained as sightings of Earth-based aircraft, known astronomical objects, or as hoaxes.[181] Nonetheless, a certain fraction of the public believe that UFOs might actually be of extraterrestrial origin, and, indeed, the notion has had influence on popular culture.

The possibility of extraterrestrial life on the Moon was ruled out in the 1960s, and during the 1970s it became clear that most of the other bodies of the Solar System do not harbor highly developed life, although the question of primitive life on bodies in the Solar System remains open.

Recent history

The failure so far of the SETI program to detect an intelligent radio signal after decades of effort has at least partially dimmed the prevailing optimism of the beginning of the space age. Notwithstanding, belief in extraterrestrial beings continues to be voiced in pseudoscience, conspiracy theories, and in popular folklore, notably "Area 51" and legends. It has become a pop culture trope given less-than-serious treatment in popular entertainment.In the words of SETI's Frank Drake, "All we know for sure is that the sky is not littered with powerful microwave transmitters".[182] Drake noted that it is entirely possible that advanced technology results in communication being carried out in some way other than conventional radio transmission. At the same time, the data returned by space probes, and giant strides in detection methods, have allowed science to begin delineating habitability criteria on other worlds, and to confirm that at least other planets are plentiful, though aliens remain a question mark. The Wow! signal, detected in 1977 by a SETI project, remains a subject of speculative debate.

In 2000, geologist and paleontologist Peter Ward and astrobiologist Donald Brownlee published a book entitled Rare Earth: Why Complex Life is Uncommon in the Universe.[183] In it, they discussed the Rare Earth hypothesis, in which they claim that Earth-like life is rare in the universe, whereas microbial life is common. Ward and Brownlee are open to the idea of evolution on other planets that is not based on essential Earth-like characteristics (such as DNA and carbon).

Theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking in 2010 warned that humans should not try to contact alien life forms. He warned that aliens might pillage Earth for resources. "If aliens visit us, the outcome would be much as when Columbus landed in America, which didn't turn out well for the Native Americans", he said.[184] Jared Diamond had earlier expressed similar concerns.[185]

In November 2011, the White House released an official response to two petitions asking the U.S. government to acknowledge formally that aliens have visited Earth and to disclose any intentional withholding of government interactions with extraterrestrial beings. According to the response, "The U.S. government has no evidence that any life exists outside our planet, or that an extraterrestrial presence has contacted or engaged any member of the human race."[186][187] Also, according to the response, there is "no credible information to suggest that any evidence is being hidden from the public's eye."[186][187] The response noted "odds are pretty high" that there may be life on other planets but "the odds of us making contact with any of them—especially any intelligent ones—are extremely small, given the distances involved."[186][187]

In 2013, the exoplanet Kepler-62f was discovered, along with Kepler-62e and Kepler-62c. A related special issue of the journal Science, published earlier, described the discovery of the exoplanets.[188]

On 17 April 2014, the discovery of the Earth-size exoplanet Kepler-186f, 500 light-years from Earth, was publicly announced;[189] it is the first Earth-size planet to be discovered in the habitable zone and it has been hypothesized that there may be liquid water on its surface.

On 13 February 2015, scientists (including Geoffrey Marcy, Seth Shostak, Frank Drake and David Brin) at a convention of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, discussed Active SETI and whether transmitting a message to possible intelligent extraterrestrials in the Cosmos was a good idea;[190][191] one result was a statement, signed by many, that a "worldwide scientific, political and humanitarian discussion must occur before any message is sent".[192]

On 20 July 2015, British physicist Stephen Hawking and Russian billionaire Yuri Milner, along with the SETI Institute, announced a well-funded effort, called the Breakthrough Initiatives, to expand efforts to search for extraterrestrial life. The group contracted the services of the 100-meter Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia in the United States and the 64-meter Parkes Telescope in New South Wales, Australia.