Presentation of Marie Antoinette to Louis Auguste at Versailles, before their marriage. She was married at age 15, on 16 May 1770.

Child marriage is a formal marriage or informal union entered into by an individual before reaching a certain age, specified by several global organizations such as UNICEF as minors under the age of 18. The legally prescribed marriageable age in some jurisdictions is below 18 years, especially in the case of girls; and even when the age is set at 18 years, many jurisdictions permit earlier marriage with parental consent or in special circumstances, such as teenage pregnancy. In certain countries, even when the legal marriage age is 18, cultural traditions take priority over legislative law. Child marriage violates the rights of children; it affects both boys and girls, but it is more common among girls. Child marriage has widespread and long term consequences for child brides and grooms. According to several UN agencies, comprehensive sexuality education can prevent such a phenomenon.

Child marriage is related to child betrothal, and it includes civil cohabitation and court approved early marriages after teenage pregnancy. In many cases, only one marriage-partner is a child, usually the female. Causes of child marriages include poverty, bride price, dowry, cultural traditions, laws that allow child marriages, religious and social pressures, regional customs, fear of remaining unmarried, illiteracy, and perceived inability of women to work for money.

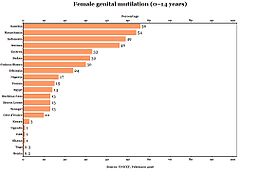

Child marriages were common throughout history for a variety of reasons including poverty, insecurity, as well as for political and financial reasons. Today, child marriage is still fairly widespread, particularly in developing countries, such as parts of Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, West Asia, Latin America, and Oceania. However, even in developed countries such as the United States legal exceptions mean that 25 US states have no minimum age requirement. The incidence of child marriage has been falling in most parts of the world. The countries with the highest observed rates of child marriages below the age of 18 are Niger, Chad, Mali, Bangladesh, Guinea and the Central African Republic, with a rate above 60%. Niger, Chad, Bangladesh, Mali and Ethiopia were the countries with child marriage rates greater than 20% below the age of 15, according to 2003–2009 surveys.

History

Child marriages were common in history. Princess Emilia of Saxony in 1533, at age 16 married George the Pious, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, then aged 48 years.

Historically, child marriage was common around the world, the average life expectancy did not exceed 50 years old, so child marriage was considered an effective practice to increase population. The practice began to be questioned in the 20th century, with the age of individuals' first marriage increasing in many countries and most countries increasing the minimum marriage age.

In ancient and medieval societies it was common for girls to be betrothed at or even before puberty. As Friedman claims, "arranging and contracting the marriage of a young girl were the undisputed prerogatives of her father in ancient Israel." Most girls were married before the age of 15, often at the start of their puberty. In the Middle Ages the age at marriage seems to have been around puberty throughout the Jewish world.

Ruth Lamdan writes: “The numerous references to child marriage in the 16th- century Responsa literature and other sources, shows that child marriage was so common, it was virtually the norm. In this context, it is important to remember that in halakha, the term ‘minor’ refers to a girl under twelve years and a day. A girl aged twelve and a half was already considered an adult in all respects.”

In Ancient Greece, early marriage and motherhood for girls was encouraged. Even boys were expected to marry in their teens. Early marriages and teenage motherhood was typical. In Ancient Rome, girls married above the age of 12 and boys above 14. In the Middle Ages, under English civil laws that were derived from Roman laws, marriages before the age of 16 were common. In Imperial China, child marriage was the norm.

Religion

Most religions, over history, influenced the marriageable age. For example, Christian ecclesiastical law forbade marriage of a girl before the age of puberty. Hindu vedic scriptures mandated the age of a girl's marriage to be adulthood which they defined as three years after the onset of puberty.Jewish scholars and rabbis strongly discouraged marriages before the onset of puberty, but at the same time, in exceptional cases, girls ages 3 through 12 (the legal age of consent according to halakha) might be given in marriage by her father. By Judaism, the minimal girl age, for marriage, was 12 years and one day, "na'arah", as metioned in the ancient Talmud Mishnah books,(copiled between 536 BCE – 70 CE, redacted in the 3rd century CE), Order Nashim Masechet Kiddushin 41 a & b.

According to Halakha girls should not marry until they are 12 years and six months old, "bogeret". Although Moses Maimonides mentions in Talmud Mishneh Torah (compiled between 1170 and 1180 CE) that in exceptional cases, girls ages three through 12, might be given in marriage by her father, he also clarifies, in the same chapter, in verse 3:19 that: "Although a father has the option of consecrating his daughter to anyone he desires while she is a minor or while she is a maiden, it is not proper for him to act in this manner".

Some apocryphal accounts state that at the time of her betrothal to Joseph, Mary, the mother of Jesus, was 12–14 years old, but such accounts are unreliable.

Historically within the Catholic Church, prior to the 1917 Code of Canon Law, the minimum age for a dissoluble betrothal (sponsalia de futuro) was 7 years in the contractees. The minimum age for a valid marriage was puberty, or nominally 14 for males and 12 for females. The 1917 Code of Canon Law raised the minimum age for a valid marriage at 16 for males and 14 for females. The 1983 Code of Canon Law maintained the minimum age for a valid marriage at 16 for males and 14 for females.

Some Islamic marriage practices have permitted marriage of girls below the age of 10, because Shariat law is based in part on the life and practices of Muhammad, the Prophet, as described in part in Sahih Bukhari and Sahih Muslim. Muhammad married Aisha, his third wife, when she was about age six, and consummated the marriage when she was about age nine. Some mainstream Islamic scholars have suggested that it is not the chronological age that matters; marriageable age under Muslim religious law is the age when the guardians of the girl feel she has reached sexual maturity. Such determination of sexual maturity is a matter of subjective judgment, and there is a strong belief among most Muslims and scholars, based on Sharia, that marrying a girl less than 13 years old is an acceptable practice for Muslims.

Effects on each gender

Christian child marriage in the Middle Ages

Boys

Boys are sometimes married as children, although according to UNICEF, "girls are disproportionately the most affected", child marriage is five times more common among girls than boys. Research on the effects of child marriage on underage boys is small. As of September 2014, 156 million living men were married as underage boys.Girls

Child marriage has lasting consequences on girls, from their health, education and social development perspectives. These consequences last well beyond adolescence. One of the most common causes of death for girls aged 15 to 19 in developing countries was pregnancy and childbirth. In Niger, which is estimated as having the highest rate of child marriage in the world, about 3 in 4 girls marry before their 18th birthday.Causes of child marriage

According to UNFPA, factors that promote and reinforce child marriage include poverty and economic survival strategies; gender inequality; sealing land or property deals or settling disputes; control over sexuality and protecting family honour; tradition and culture; and insecurity, particularly during war, famine or epidemics. Other factors include family ties in which marriage is a means of consolidating powerful relations between families.Dowry and brideprice

A traditional, formal presentation of the bride price at a Thai engagement ceremony.

Providing a girl with a dowry at her marriage is an ancient practice which continues in some parts of the world. This requires parents to bestow property on the marriage of a daughter, which is often an economic challenge for many families. The difficulty to save and preserve wealth for dowry was common, particularly in times of economic hardship, or persecution, or unpredictable seizure of property and savings. These difficulties pressed families to betroth their girls, irrespective of her age, as soon as they had the resources to pay the dowry. Thus, Goitein notes that European Jews would marry their girls early, once they had collected the expected amount of dowry.

A bride price is the amount paid by the groom to the parents of a bride for them to consent to him marrying their daughter. In some countries, the younger the bride, the higher the price she may fetch. This practice creates an economic incentive where girls are sought and married early by her family to the highest bidder. Child marriages of girls is a way out of desperate economic conditions, or simply a source of income to the parents. Bride price is another cause of child marriage and child trafficking.

Persecution, forced migration, and slavery

Social upheavals such as wars, major military campaigns, forced religious conversion, taking natives as prisoners of war and converting them into slaves, arrest and forced migrations of people often made a suitable groom a rare commodity. Bride's families would seek out any available bachelors and marry them to their daughters, before events beyond their control moved the boy away. Persecution and displacement of Roma and Jewish people in Europe, colonial campaigns to get slaves from various ethnic groups in West Africa across the Atlantic for plantations, Islamic campaigns to get Hindu slaves from India across Afghanistan's Hindu Kush as property and for work, were some of the historical events that increased the practice of child marriage before the 19th century.Among Sephardi Jewish communities, child marriages became frequent from the 10th to 13th centuries, especially in Muslim Spain. This practice intensified after the Jewish community was expelled from Spain, and resettled in the Ottoman Empire. Child marriages among the Eastern Sephardic Jews continued through the 18th century in Islamic majority regions.

Fear, poverty, social pressures and sense of protection

English stage actress Ellen Terry was married at age 16 to George Frederic Watts

who was 46 years old, a marriage her parents thought would be

advantageous; later she said she was uncomfortable being a child bride.

Terry died at the age of 81, in 1928.

A sense of social insecurity has been a cause of child marriages across the world. For example, in Nepal, parents fear likely social stigma if adult daughters (past 18 years) stay at home. Other fear of crime such as rape, which not only would be traumatic but may lead to less acceptance of the girl if she becomes victim of a crime. For example, girls may not be seen as eligible for marriage if they are not virgins. In other cultures, the fear is that an unmarried girl may engage in illicit relationships, or elope causing a permanent social blemish to her siblings, or that the impoverished family may be unable to find bachelors for grown up girls in their economic social group. Such fears and social pressures have been proposed as causes that lead to child marriages. Insofar as child marriage is a social norm in practicing communities, the elimination of child marriage must come through a changing of those social norms. The mindset of the communities, and what is believed to be the proper outcome for a child bride, must be shifted to bring about a change in the prevalence of child marriage.

Extreme poverty may make daughters an economic burden on the family, which may be relieved by their early marriage, to the benefit of the family as well as the girl herself. Poor parents may have few alternatives they can afford for the girls in the family; they often view marriage as a means to ensure their daughter's financial security and to reduce the economic burden of a growing adult on the family. Child marriage can also be seen as means of ensuring a girl's economic security, particularly if she lacks family members to provide for her. In reviews of Jewish community history, scholars claim poverty, shortage of grooms, uncertain social and economic conditions were a cause for frequent child marriages.

Drawings by young Syrian refugee girls in a community centre in southern Lebanon promote the prevention of child marriage.

An additional factor causing child marriage is the parental belief that early marriage offers protection. Parents feel that marriage provides their daughter with a sense of protection from sexual promiscuity and safe from sexually transmitted infections. However, in reality, young girls tend to marry older men, placing them at an increased risk of contracting a sexually transmitted infection.

Protection through marriage may play a specific role in conflict settings. Families may have their young daughters marry members of an armed group or military in hopes that she will be better protected. Girls may also be taken by armed groups and forced into marriages.

Religion, culture and civil law

Although the general marriageable age is 18 in the majority of countries, most jurisdictions allow for exceptions for underage youth with parental and/or judicial consent. Such laws are neither limited to developing countries, nor to state religion. In some countries a religious marriage by itself has legal validity, while in others it does not, as civil marriage is obligatory. For Catholics incorporated into the Latin Church, the 1983 Code of Canon Law sets the minimum age for a valid marriage at 16 for males and 14 for females. In 2015, Spain raised its minimum marriageable age to 18 (16 with court concent) from the previous 14. In Mexico, marriage under 18 is allowed with parental consent, from age 14 for girls and age 16 for boys. In Ukraine, in 2012, the Family Code was amended to equalize the marriageable age for girls and boys to 18, with courts being allowed to grant permission to marry from age 16 years if it is established that the marriage is in the best interest of the youth.Many states in the US permit child marriages, with court's permission. Since 2015, the minimum marriageable age throughout Canada is 16. In Canada the age of majority is set by province/territory at 18 or 19, so minors under this age have additional restrictions (i.e. parental and court consent). Under the Criminal Code, Art. 293.2 Marriage under age of 16 years reads: "Everyone who celebrates, aids or participates in a marriage rite or ceremony knowing that one of the persons being married is under the age of 16 years is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years." The Civil Marriage Act also states: "2.2 No person who is under the age of 16 years may contract marriage." In the UK, marriage is allowed for 16–17 years old with parental consent in England and Wales as well as in Northern Ireland, and even without parental consent in Scotland. However, a marriage of a person under 16 is void under the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973. The United Nations Population Fund stated the following:

In 2010, 158 countries reported that 18 years was the minimum legal age for marriage for women without parental consent or approval by a pertinent authority. However, in 146 countries, state or customary law allows girls younger than 18 to marry with the consent of parents or other authorities; in 52 countries, girls under age 15 can marry with parental consent. In contrast, 18 is the legal age for marriage without consent among males in 180 countries. Additionally, in 105 countries, boys can marry with the consent of a parent or a pertinent authority, and in 23 countries, boys under age 15 can marry with parental consent.Lower legally allowed marriage age does not necessarily cause high rates of child marriages. However, there is a correlation between restrictions placed by laws and the average age of first marriage. In the United States, per 1960 Census data, 3.5% of girls married before the age of 16, while an additional 11.9% married between 16 and 18. States with lower marriage age limits saw higher percentages of child marriages. This correlation between higher age of marriage in civil law and observed frequency of child marriages breaks down in countries with Islam as the state religion. In Islamic nations, many countries do not allow child marriage of girls under their civil code of laws. But, the state recognized Sharia religious laws and courts in all these nations have the power to override the civil code, and often do. UNICEF reports that the top five nations in the world with highest observed child marriage rates – Niger (75%), Chad (72%), Mali (71%), Bangladesh (64%), Guinea (63%) – are Islamic majority countries.

Marriageable age in religious sources

Catholic Church

| Male consent | Female consent | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catholic Church | 16 | 14 | Diriment impediment (can. 1083 § 1). Conferences of Bishops can adopt a higher age for liceity (§ 2). Marriage against the worldly power's directive need permission by the Ordinary for liceity (can. 1071 § 1 no. 2), which in case of sensible and equal laws regarding marriage age is regularly not granted. The permission by the Ordinary is also required in case of a marriage of a minor child (i.e. under 18 years old) when his parents are unaware of his marriage or if his parents reasonably oppose his marriage (can. 1071 § 1 no. 6). |

Islam

In Quran, the "age of marriage" coincides with puberty. Classical Islamic law (Sharia) does not have a marriageable age because there is no minimum age at which puberty can occur. In Islam there is no set age for marriage, the condition is physical (bulugh) maturity and mental (rushd) maturity. So the age is variable. The Prophet Muhammad, who is said to serve as a role model (qudwah hasanah) for every Muslim, is reported by Sunni Hadith sources to have married Aisha when she was six or seven years old, with the marriage not being consummated until she had reached the age of nine or ten years old.Büchler and Schlater observe that "marriageable age according to classical Islamic law coincides with the occurrence of puberty. The notion of puberty refers to signs of physical maturity such as the emission of semen or the onset of menstruation", but then claim the schools of Islamic jurisprudence (madhaahib) set the following marriageable ages for men and women.

| Male consent | Female consent | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shafi'i | 15 | 15 | |

| Hanbali | 15 | 15 | |

| Maliki | 17 | 17 | |

| Jafari | 15 | 9 | |

| Hanafi | 12 | 9 |

However other sources give different ages.

The Reliance of the Traveller, frequently considered the definitive summary of Shafi'i jurisprudence, states in the chapter on marriage as follows:

-

- 32.2a. A father arranging the marriage of a virgin daughter: A father can arrange the marriage of his virgin daughter without her permission even if she is beyond the age of puberty. It is up to him whether he consults her or not.

- 32.2b. Someone other than the father arranging the marriage of a virgin: However, if anyone other than the father is arranging the marriage of a virgin, such as a guardian appointed in the father's will or anyone else, he cannot give her in marriage unless she is beyond the age of puberty and has given her consent. In this case her silence is taken as consent.

Hinduism

The Manu Smriti recommends arranged marriages for girls within three years from attainment of puberty (11-14). If unmarried, after this period, the girl may marry on her own will somebody from her own caste and rank by freewill (after 14). A man, aged thirty years, shall marry a maiden of twelve who pleases him, or a man of twenty-four a girl eight years of age; if (the performance of) his duties would (otherwise) be impeded, (he must marry) sooner.Politics and financial relationships

Child marriage in 1697 of Marie Adélaïde of Savoy, age 12 to Louis, heir apparent of France age 15. The marriage created a political alliance.

Child marriages may depend upon socio-economic status. The aristocracy in some cultures, as in the European feudal era tended to use child marriage as a method to secure political ties. Families were able to cement political and/or financial ties by having their children marry. The betrothal is considered a binding contract upon the families and the children. The breaking of a betrothal can have serious consequences both for the families and for the betrothed individuals themselves.

Affects of child marriage on global regions

A UNFPA report stated that "For the period 2000–2011, just over one third (an estimated 34 per cent) of women aged 20 to 24 years in developing regions were married or in union before their eighteenth birthday. In 2010 this was equivalent to almost 67 million women. About 12 per cent of them were married or in union before age 15." The prevalence of child marriage varies substantially among countries. Around the world, girls from rural areas are twice as likely to marry as children as those from urban areas.Africa

Poster against child and forced marriage

According to UNICEF, Africa has the highest incidence rates of child marriage, with over 70% of girls marrying under the age of eighteen in three nations. Girls in West and Central Africa have the highest risk of marrying in childhood. Niger has one of the highest rates of early marriage in sub-Saharan Africa. Among Nigerian women between the ages of twenty and twenty-four, 76% reported marrying before the age of eighteen and 28% reported marrying before the age of fifteen. This UNICEF report is based on data that is derived from a small sample survey between 1995 and 2004, and the current rate is unknown given lack of infrastructure and in some cases, regional violence.

African countries have enacted marriageable age laws to limit marriage to a minimum age of 16 to 18, depending on jurisdiction. In Ethiopia, Chad and Niger, the legal marriage age is 15, but local customs and religious courts have the power to allow marriages below 12 years of age. Child marriages of girls in West Africa and Northeast Africa are widespread. Additionally, poverty, religion, tradition, and conflict make the rate of child marriage in Sub-Saharan Africa very high in some regions.

In many tribal systems a man pays a bride price to the girl's family in order to marry her (comparable to the customs of dowry and dower). In many parts of Africa, this payment, in cash, cattle, or other valuables, decreases as a girl gets older. Even before a girl reaches puberty, it is common for a married girl to leave her parents to be with her husband. Many marriages are related to poverty, with parents needing the bride price of a daughter to feed, clothe, educate, and house the rest of the family. In Mali, the female:male ratio of marriage before age 18 is 72:1; in Kenya, 21:1.

The various reports indicate that in many Sub-Saharan countries, there is a high incidence of marriage among girls younger than 15. Many governments have tended to overlook the particular problems resulting from child marriage, including obstetric fistulae, premature births, stillbirth, sexually transmitted diseases (including cervical cancer), and malaria.

In parts of Ethiopia and Nigeria many girls are married before the age of 15, some as young as 7. In parts of Mali 39% of girls are married before the age of 15. In Niger and Chad, over 70% of girls are married before the age of 18.

As of 2006, 15–20% of school dropouts in Nigeria were the result of child marriage. In 2013, Nigeria attempted to change Section 29, subsection 4 of its laws and thereby prohibit child marriages. Christianity and Islam are each practiced by roughly half of its population, and the country continues with personal laws from its British colonial era laws, where child marriages are forbidden for its Christians and allowed for its Muslims. Child marriage is a divisive topic in Nigeria and widely practiced. In northern states, predominantly Muslim, over 50% of the girls marry before the age of 15.

In 2016, during a feast ending the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, the Gambian President Yahya Jammeh announced that child and forced marriages were banned.

In 2015, Malawi passed a law banning child marriage, which raises the minimum age for marriage to 18. This major accomplishment came following years of effort by the Girls Empowerment Network campaign, which ultimately led to tribal and traditional leaders banning the cultural practice of child marriage.

In Morocco, child marriage is a common practice. Over 41,000 marriages every year involve child brides. Before 2003, child marriages did not require a court or state's approval. In 2003, Morocco passed the family law (Moudawana) that raised minimum age of marriage for girls from 14 to 18, with the exception that underage girls may marry with the permission of the government recognized official/court and girl's guardian. Over the 10 years preceding 2008, requests for child marriages have been predominantly approved by Morocco's Ministry for Social Development, and have increased (c. 29% of all marriages). Some child marriages in Morocco are a result of Article 475 of the Moroccan penal code, a law that allows rapists to avoid punishment if they marry their underage victims. Article 475 was amended in January 2014 after much campaigning, and rapists can legally no longer avoid sentencing by marrying their victim.

In South Africa the law provides for respecting the marriage practices of traditional marriages, whereby a person might be married as young as 12 for females and 14 for males. Early marriage is cited as "a barrier to continuing education for girls (and boys)". This includes absuma (arranged marriages set up between cousins at birth in local Islamic ethnic group), bride kidnapping and elopement decided on by the children.

In 2016, the Tanzanian High Court – in a case filed by the Msichana Initiative, a lobbying group that advocates for girls' right to education – ruled in favor of protecting girls from the harms of early marriage. It is now illegal for anyone younger than 18 to marry in Tanzania.

A 2015 Human Rights Watch report stated that in Zimbabwe, one-third of women aged between 20 and 49 years old had married before reaching the age of 18. In January 2016, two women who had been married as children brought a court case requesting a change in the legal age of marriage to the Constitutional Court, with the result that the court declared that 18 is to be the minimum age for a legal marriage for both men and women (previously the legal age had been 16 for women and 18 for men). The law took effect immediately, and was hailed by a number of human rights, women's rights, medical and legal groups as a landmark ruling for the country.

The UN states that although the number of child marriages has declined on a worldwide scale, the problem remains most severe in Africa, despite the fact that Ethiopia cut child marriage rates by a third.

Americas

Child marriage is common in Latin America and the Caribbean island nations. About 29% of girls are married before age 18. The child marriage incidence rates varies between the countries, with Dominican Republic, Honduras, Brazil, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Haiti and Ecuador reporting some of the highest rates in the Americas. Bolivia and Guyana have shown the sharpest decline in child marriage rates as of 2012. In Guatemala, early marriage is most common among indigenous Mayan communities. Brazil is ranked fourth in the world in terms of absolute numbers of girls married or co-habitating by age fifteen. Poverty and lack of laws mandating minimum age for marriage have been cited as reasons of child marriage in Latin America. In an effort to combat the widespread belief among poor, rural, and indigenous communities that child marriage is a route out of poverty, some NGOs are working with communities in Latin America to shift norms and create safe spaces for adolescent girls.Canada

Since 2015, the minimum marriageable age throughout Canada is 16. In Canada the age of majority is set by province/territory at 18 or 19, so minors under this age have additional restrictions (i.e. parental and court consent). Under the Criminal Code, Art. 293.2 Marriage under age of 16 years reads: "Everyone who celebrates, aids or participates in a marriage rite or ceremony knowing that one of the persons being married is under the age of 16 years is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years." The Civil Marriage Act also states: "2.2 No person who is under the age of 16 years may contract marriage."United States

Child marriage, as defined by UNICEF, is observed in the United States. The UNICEF definition of child marriage includes couples who are formally married, or who live together as a sexually active couple in an informal union, with at least one member – usually the girl – being less than 18 years old. The latter practice is more common in the United States, and it is officially called cohabitation. According to a 2010 report by National Center for Health Statistics, an agency of the government of United States, 2.1% of all girls in the 15–17 age group were in a child marriage. In the age group of 15–19, 7.6% of all girls in the United States were formally married or in an informal union. The child marriage rates were higher for certain ethnic groups and states. In Hispanic groups, for example, 6.6% of all girls in the 15–17 age group were formally married or in an informal union, and 13% of the 15–19 age group were. Over 350,000 babies are born to teenage mothers every year in the United States, and over 50,000 of these are second babies to teen mothers.Laws regarding child marriage vary in the different states of the United States. Generally, children 16 and over may marry with parental consent, with the age of 18 being the minimum in all but two states to marry without parental consent. However all states but Delaware and New Jersey have exceptions for child marriage within their laws, and although those under 16 generally require a court order in addition to parental consent, when those exceptions are taken into account, 25 US states have no minimum age requirement. Those that do have set it as young as 13 or 14.

In 2018, Delaware became the first state to ban child marriage without exceptions, followed by New Jersey the same year.

Between 2000 and 2015 there were at least 207,468 child marriages in the United States of which over 1,000 marriage licences were for children under 15, some as young as ten years old.

Until 2008 the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints practiced child marriage through the concept of "spiritual marriage" as soon as girls were ready to bear children, as part of its polygamy practice, but laws have raised the age of legal marriage in response to criticism of the practice. In 2008 the Church changed its policy in the United States to no longer marry individuals younger than the local legal age. In 2007 church leader Warren Jeffs was convicted of being an accomplice to statutory rape of a minor due to arranging a marriage between a 14-year-old girl and a 19-year-old man. In March 2008 officials of the state of Texas believed that children at the Yearning For Zion Ranch were being married to adults and were being abused. The state of Texas removed all 468 children from the ranch and placed them into temporary state custody. After the Austin's 3rd Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court of Texas ruled that Texas acted improperly in removing them from the YFZ Ranch, the children were returned to their parents or relatives.

Musician Jerry Lee Lewis's third wife, Myra Gale Brown, was Lewis's first cousin once removed and was only 13 years old at the time.

Asia

Child marriage in India. In 1900, Rana Prathap Kumari age 12 married Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV age 16. Two years later, he was recognized as the King of Mysore under British India.

More than half of all child marriages occur in the South Asian countries of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal. There was a decrease in the rates of child marriage across South Asia from 1991 to 2007, but the decrease was observed among young adolescent girls and not girls in their late teens. Some scholars believe this age-specific reduction was linked to girls increasingly attending school until about age 15 and then getting married.

Western Asia

A 2013 report claims 53% of all married women in Afghanistan were married before age 18, and 21% of all were married before age 15. Afghanistan's official minimum age of marriage for girls is 15 with her father's permission. In all 34 provinces of Afghanistan, the customary practice of ba'ad is another reason for child marriages; this custom involves village elders, jirga, settling disputes between families or unpaid debts or ruling punishment for a crime by forcing the so-called guilty family to give their 5- to 12-year-old girls as a wife. Sometimes a girl is forced into child marriage for a crime her uncle or distant relative is alleged to have committed.Over half of Yemeni girls are married before 18, some by the age eight. Yemen government's Sharia Legislative Committee has blocked attempts to raise marriage age to either 15 or 18, on grounds that any law setting minimum age for girls is un-Islamic. Yemeni Muslim activists argue that some girls are ready for marriage at age 9. According to HRW, in 1999 the minimum marriage age 15 for women was abolished; the onset of puberty, interpreted by conservatives to be at age nine, was set as a requirement for consummation of marriage. In practice "Yemeni law allows girls of any age to wed, but it forbids sex with them until the indefinite time they're 'suitable for sexual intercourse'." As with Africa, the marriage incidence data for Yemen in HRW report is from surveys between 1990 and 2000. Current data is difficult to obtain, given regional violence.

In April 2008, Nujood Ali, a 10-year-old girl, successfully obtained a divorce after being raped under these conditions. Her case prompted calls to raise the legal age for marriage to 18. Later in 2008, the Supreme Council for Motherhood and Childhood proposed to define the minimum age for marriage at 18 years. The law was passed in April 2009, with the age voted for as 17. But the law was dropped the following day following maneuvers by opposing parliamentarians. Negotiations to pass the legislation continue. Meanwhile, Yemenis inspired by Nujood's efforts continue to push for change, with Nujood involved in at least one rally. In September 2013, an 8-year-old girl died of internal bleeding and uterine rupture on her wedding night after marrying a 40-year-old man.

The widespread prevalence of child marriage in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has been documented by human rights groups. Saudi clerics have justified the marriage of girls as young as 9, with sanction from the judiciary. There are no laws in place defining a minimum age of consent in Saudi Arabia, though drafts for possible laws have been created since 2011.

Research by the United Nations Population Fund indicates that 28.2% of marriages in Turkey – almost one in three – involve girls under 18.

Child marriage was also found to be prevalent among Syrian and Palestinian Syrian refugees in Lebanon, in addition to other forms of sexual and gender-based violence. Marriage was seen as a potential way to protect family honor and protect a girl from rape given how common rape was during the conflict. Incidents of child marriages increased in Syria and among Syrian refugees over the course of the conflict. The proportion of Syrian refugee girls living in Jordan who were married increased from 13% in 2011 to 32% in 2014. Journalists Magnus Wennman and Carina Bergfeldt documented the practice, and some of its results.

Southeast Asia

A couple after celebrating their child marriage in Indonesia, about 1939.

Hill tribes girls are often married young. For the Karen people it is possible that two couples can arrange their children's marriage before the children are born.

Indonesia

In Indonesia, there are reports of Muslim clerics taking multiple underage wives, some less than 12 years old. Indonesian prosecutors have attempted to stop this practice by demanding prison terms for such clerics; however, local courts have issued soft sentences.

A young bride at her Nikah.

In Indonesia the 1974 Law on Marriage stipulates that a woman must be at least 16 years old and a man must be at least 19 years old to marry. With the popular rise of social networking sites like Facebook underage marriage appears to be increasing in areas like Gunung Kidul, Yogyakarta. Couples have reported becoming acquainted through Facebook and continuing their relationships until girls became pregnant. Among the Atjeh of Sumatra girls formerly married before puberty. The husbands, though usually older, were still unfit for sexual union. Among the islanders of Fiji, also, marriage took place before puberty.

Malaysia

In Malaysia, the public was shocked when they learned that a 41-year-old Malaysian weds a 11-year-old girl in Golok, a border town in southern Thailand. The man, who already has two wives and six children, is said to be the imam of a surau at a village in Gua Musang, Kelantan. The matter became viral when his second wife posted photographs of the man and the young girl and their alleged solemnisation. Amid public outrage, parents of the 11-year-old girl defend decision to allow their daughter's marriage to the 41-year-old man.In response to this incident, Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail said the marriage between a 41-year-old man and his 11-year-old child bride remains valid under Islam. She also said in a press statement that 'The Malaysian government "unequivocally" opposes child marriages and is already taking steps to raise the minimum age of marriage to 18. The child marriage in Gua Musang is still under active investigation by multiple agencies.

Following this controversy, Minister in the Prime Minister's Department Datuk Dr Mujahid Yusof Rawa proposed to impose a blanket ban on marriages involving under-aged children. In response, PAS Vice President Datuk Mohd Amar Nik Abdullah released a statement, saying that imposing a blanket ban on child marriage contravenes Islamic religious teachings, therefore, the blanket ban could not be accepted. "It is not wrong to marry young, from the religious perspective," he said on the sidelines of the Kelantan legislative assembly sitting. He also claimed that it is better to enforce existing laws to protect young children from being forced into unwanted early marriages.

PKR’s Latheefa Koya has taken to task the party’s president and Deputy Prime Minister Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail over the marriage of a 41-year-old man to a 11-year-old girl in Kelantan, saying all facts of the case were clear and established for the government to take action against child marriage.

Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail continues to attract criticism from activists over her perceived reluctance to take action against the 41-year-old man who married an 11-year-old child, with a coalition of women’s groups urging swift action to be taken to protect the girl, a Thai national who lives in Kelantan. The Joint Action Group for Gender Equality (JAG) said it was time to act, urging the government to conclude its lengthy investigations.

Selangor plans to amend the Islamic Family Law (State of Selangor) Enactment 2003 on the minimum age for marriage for Muslim women in the state which will be increased from 16 to 18 years, after child marriages were reported to have become rampant of late.

As the controversy surrounding the 41-year-old man who married an 11-year-old girl continues to simmer, another case of a child bride has been reported in Malaysia. The marriage involves a 19-year-old from Terengganu and a 13-year-old girl from Kelantan. They tied the knot at a mosque in Kampung Pulau Nibong on June 20. Ibrahim Husin, 67, the kadi who performed the akad nikah, said he was approached by the couple, who came with two witnesses, and a wali, who was the bride’s uncle.

Bangladesh

Child marriage rates in Bangladesh are amongst the highest in the world. Every 2 out of 3 marriages involve child marriages. According to statistics from 2005, 49% of women then between 25 and 29 were married by the age of 15 in Bangladesh. According to a 2008 study, for each additional year a girl in rural Bangladesh is not married she will attend school an additional 0.22 years on average. The later girls were married, the more likely they were to utilize preventative health care. Married girls in the region were found to have less influence on family planning, higher rates of maternal mortality, and lower status in their husband's family than girls who married later.Mia's Law was enacted in 2006 to protect child brides from abuse following the torture and murder of Mia Armador, an 11-year-old who was killed by her abusive 48-year-old husband. This law requires all marriages under 13 to require special government permission.

India

According to UNICEF's "State of the World's Children-2009" report, 47% of India's women aged 20–24 were married before the legal age of 18, with 56% marrying before age 18 in rural areas. The report also showed that 40% of the world's child marriages occur in India. As with Africa, this UNICEF report is based on data that is derived from a small sample survey in 1999. The latest available UNICEF report for India uses 2004–2005 household survey data, on a small sample, and other scholars report lower incidence rates for India. According to Raj et al., the 2005 small sample household survey data suggests 22% of girls ever married aged 16–18, 20% of girls in India were married between 13–16, and 2.6% were married before age 13. According to 2011 nationwide census of India, the average age of marriage for women in India is 21. The child marriage rates in India, according to a 2009 representative survey, dropped to 7%. In its 2001 demographic report, the Census of India stated zero married girls below age 10, 1.4 million married girls out of 59.2 million girls in the age 10–14, and 11.3 million married girls out of 46.3 million girls in the age 15–19 (which includes 18–19 age group). For 2011, the Census of India reports child marriage rates dropping further to 3.7% of females aged less than 18 being married.The Child Marriage Restraint Act 1929 was passed during the tenure of British rule on Colonial India. It forbade the marriage of a male younger than 21 or a female younger than 18 for Hindus, Buddhists, Christians and most people of India. However, this law did not and currently does not apply to India's 165 million Muslim population, and only applies to India's Hindu, Christian, Jain, Sikh and other religious minorities. This link of law and religion was formalized by the British colonial rule with the Muslim personal laws codified in the Indian Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act of 1937. The age at which India's Muslim girls can legally marry, according to this Muslim Personal Law, is 9, and can be lower if her guardian (wali) decides she is sexually mature. Over the last 25 years, All India Muslim Personal Law Board and other Muslim civil organizations have actively opposed India-wide laws and enforcement action against child marriages; they have argued that Indian Muslim families have a religious right to marry a girl aged 15 or even 12. Several states of India claim specially high child marriage rates in their Muslim and tribal communities. India, with a population of over 1.2 billion, has the world's highest total number of child marriages. It is a significant social issue. As of 2016, the situation has been legally rectified by The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006.

According to "National Plan of Action for Children 2005", published by Indian government's Department of Women and Child Development, set a goal to eliminate child marriage completely by 2010. In 2006, The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006 was passed to prohibit solemnization of child marriages. This law states that men must be at least 21 years of age and women must but be at least 18 years of age to marry.

Some Muslim organizations planned to challenge the new law in the Supreme Court of India. In latter years, various high courts in India – including the Gujarat High Court, the Karnataka High Court and the Madras High Court – have ruled that the act prevails over any personal law (including Muslim personal law).

Nepal

UNICEF reported that 28.8% of marriages in Nepal were child marriages as of 2011. A UNICEF discussion paper determined that 79.6 percent of Muslim girls in Nepal, 69.7 percent of girls living in hilly regions irrespective of religion, and 55.7 percent of girls living in other rural areas, are all married before the age of 15. Girls who were born into the highest wealth quintile marry about two years later than those from the other quintiles.Pakistan

According to two 2013 reports, over 50% of all marriages in Pakistan involve girls less than 18 years old. Another UNICEF report claims 70 per cent of girls in Pakistan are married before the age of 16. As with India and Africa, the UNICEF data for Pakistan is from a small sample survey in the 1990s.The exact number of child marriages in Pakistan below the age of 13 is unknown, but rising according to the United Nations. Andrew Bushell claims rate of marriage of 8- to 13-year-old girls exceeding 50% in northwest regions of Pakistan.

Another custom in Pakistan, called swara or vani, involves village elders solving family disputes or settling unpaid debts by marrying off girls. The average marriage age of swara girls is between 5 and 9. Similarly, the custom of watta satta has been cited as a cause of child marriages in Pakistan.

According to Population Council, 35% of all females in Pakistan become mothers before they reach the age of 18, and 67% have experienced pregnancy – 69% of these have given birth – before they reach the age of 19. Less than 4% of married girls below the age of 19 had some say in choosing her spouse; over 80% were married to a near or distant relative. Child marriage and early motherhood is common in Pakistan.

Iran

The legal age of marriage in Iran for girls is 13 years old; however, some girls are forced into marriage as young as below the age of 10 years old. The same source pointed out that "child marriages are more common in socially backward rural areas often afflicted with high levels of illiteracy and drug addiction". The U.N. Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) examining child marriage in Iran has warned of a rising number of young girls forced into marriage in Iran. The Committee deplored the fact that the State party allows sexual intercourse involving girls as young as 9 lunar years and that other forms of sexual abuse of even younger children is not criminalized. CRC said that Tehran must "repeal all provisions that authorize, condone or lead to child sexual abuse" and called for the age of sexual consent to be increased from nine years old to 16. The Society For Protecting The Rights of The Child said that 43,459 girls aged under 15 had married in 2009. In 2010, 716 girls under the age of 10 had married, up from 449 in the year prior. On 8 March 2018 a member of the Tehran City Council, Shahrbanoo Amani said that there were 15,000 widows under the age of 15 in the country.Europe

General

Each European country has its own laws; in both the European Union and the Council of Europe the marriageable age falls within the jurisdiction of individual member states. The Istanbul convention, the first legally binding instrument in Europe in the field of violence against women and domestic violence, only requires countries which ratify it to prohibit forced marriage (Article 37) and to ensure that forced marriages can be easily voided without further victimization (Article 32), but does not make any reference to a minimum age of marriage.European Union

In the European Union, the general age of marriage as a right is 18 in all member states, except in Scotland where it is 16. When all exceptions are taken into account (such as judicial or parental consent), the minimum age is 16 in most countries, and in Estonia it is 15. In 3 countries marriage under 18 is completely prohibited. By contrast, in 9 countries there is no set minimum age, although all these countries require the authorization of a public authority (such as judge or social worker) for the marriage to take place.| State | Minimum age | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum age when all exceptions are taken into account | General age | ||

| 16 | 18 | 16 with parental consent. | |

| none | 18 | Younger with judicial consent (with no strict minimum age). With parental consent, serious reasons are required for a minor to marry; without parental consent, the unwillingness of the parents has to constitute an abuse. | |

| 16 | 18 | The new 2009 Family Code fixes the age at 18, but allows for an exception for 16 years olds, stating that "Upon exception, in case that important reasons impose this, matrimony may be concluded by a person at the age of 16 with permission by the regional judge". It further states that both persons wanting to marry, as well as the parents/guardians of the minor, must be consulted by the judge. (Chapter 2, Article 6) | |

| 16 | 18 | 16 with judicial consent. | |

| 16 | 18 | 16 with parental consent, if there are serious reasons for the marriage. | |

| 16 | 18 | Article 672 of Act No. 89/2012 Coll. the Civil Code (which came into force in 2014) states that the court may, in exceptional cases, allow a marriage of a 16 year old, if there are serious reasons for it. | |

| 18 | 18 | Since 2017, marriage is no longer allowed under 18. | |

| 15 | 18 | 15 with court permission. | |

| none | 18 | Under 18 with judicial authorization. | |

| none | 18 | Under 18 needs judicial authorization. | |

| 18 | 18 | The minimum age was set at 18 in 2017. | |

| none | 18 | Under 18 requires court permission, which may be given if there are serious reasons for such a marriage | |

| 16 | 18 | 16 with authorization from the guardianship authority | |

| none | 18 | Under 18 with a Court Exemption Order. | |

| 16 | 18 | 16 with court consent. | |

| 16 | 18 | 16 with court consent. | |

| none girls/15 boys | 18 | 15 with court permission. Girls can marry below 15 with court permission if they are pregnant. | |

| none | 18 | Under 18 need judicial permission. New laws of 2014 fixed the marriageable at 18 for both sexes; prior to these regulations the age was 16 for females and 18 for males. The new laws still allow both sexes to obtain judicial consent to get married under 18. | |

| 16 | 18 | 16 with parental consent. | |

| 18 | 18 | Exceptions were removed by a change in the law in 2015. | |

| 16 girls/18 boys | 18 | 16 for girls with court consent. | |

| 16 | 18 | 16 with parental consent. | |

| 16 | 18 | 16 with permission from the district's administrative board. | |

| 16 | 18 | 16 with court consent, with a serious reason such as pregnancy. | |

| none | 18 | Under 18 may be approved by the Social Work Centre if there are "well founded reasons" arising upon the investigation of the situation of the minor. (Art 23, 24 of the Law on Marriage and Family Relations). | |

| 16 | 18 | 16 with court consent. | |

| 18 | 18 | Not possible to marry under the age of 18 for Swedish citizens since July 1, 2014. Authorities take a different approach to individuals who were already married when the arrive in Sweden, as during the European migrant crisis, the Swedish Migration Agency identified 132 married children, of which 65 were in Malmö. | |

| 16 | 18 (16 Scotland) | England and Wales: 16 with the consent of parents/guardians (and others in some cases) if under 18.

Scotland: 16

Northern Ireland: 16 with parental consent (with the court able to give consent in some cases). | |

In April 2016, Reuters reported "Child brides sometimes tolerated in Nordic asylum centers despite bans". For example, at least 70 girls under 18 were living as married couples in Sweden; in Norway, "some" under 16 lived "with their partners". In Denmark, it was determined there were "dozens of cases of girls living with older men", prompting Minister Inger Stojberg to state she would "stop housing child brides in asylum centres".

Marriage under 18 was completely banned in Sweden in 2014 and in Denmark in 2017. By contrast, marriage in Finland is permitted under 18 with a special judicial authorization, without any set minimum age (although in practice youth under 16 are unlikely to obtain authorization). Finland's child marriage laws have been criticized by the UN.

Balkans/Eastern Europe

In these areas, child and forced marriages are associated with the Roma community and with some rural populations. However, such marriages are illegal in most of the countries from that area. In recent years, many of those countries have taken steps in order to curb these practices, including equalizing the marriageable age of both sexes (e.g. Romania in 2007, Ukraine in 2012). Therefore, most of those 'marriages' are informal unions (without legal recognition) and often arranged from very young ages. Such practices are common in Bulgaria and Romania (in both countries the marriageable age is 18, and can only be lowered to 16 in special circumstances with judicial approval). A 2003 case involving the daughter of an informal 'gypsy king' of the area has made international news.Belgium

The Washington Post reported in April 2016 that "17 child brides" arrived in Belgium in 2015 and a further 7 so far in 2016. The same report added that "Between 2010 and 2013, the police registered at least 56 complaints about a forced marriage."Germany

In 2016 there were 1475 underage foreigners were registered in Germany, of which 1100 were girls. Syrians represented 664, Afghans 157 and Iraqis 100. In July 2016, 361 foreign children under 14 were registered as married.Netherlands

The Dutch government's National Rapporteur on Trafficking in Human Beings and Sexual Violence against Children wrote that "between September 2015 and January 2016 around 60 child brides entered the Netherlands". At least one was 14 years old. The Washington Post reported that asylum centres in the Netherlands were "housing 20 child brides between ages 13 and 15" in 2015.Russia

The common marriageable age established by the Family Code of Russia is 18 years old. Marriages of persons at age from 16 to 18 years allowed only with good reasons and by local municipal authority permission. Marriage before 16 years old may be allowed by federal subject of Russia law as an exception just in special circumstances.By 2016, a minimal age for marriage in special circumstances had been established at 14 years (in Adygea, Kaluga Oblast, Magadan Oblast, Moscow Oblast, Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, Novgorod Oblast, Oryol Oblast, Sakhalin Oblast, Tambov Oblast, Tatarstan, Vologda Oblast) or to 15 years (in Murmansk Oblast and Ryazan Oblast). Others subjects of Russia also can have marriageable age laws.

Abatement of marriageable age is an ultimate measure acceptable in cases of life threat, pregnancy and childbirth.

United Kingdom

The marriageable age in the United Kingdom is 18, or 16 with consent of parents and guardians (and others in some cases), although in Scotland no parental consent is required over 16. Scotland and Andorra are the only European jurisdictions where 16 year-olds can marry as a right (i.e. without parental or court approval).In the UK girls as young as 12 have been smuggled in to be brides of men in the Muslim community, according to a 2004 report in The Guardian. Girls trying to escape this child marriage can face death because this breaks the honor code of her husband and both families.

As with the United States, underage cohabitation is observed in the United Kingdom. According to a 2005 study, 4.1% of all girls in the 15–19 age group in the UK were cohabiting (living in an informal union), while 8.9% of all girls in that age group admitted to having been in a cohabitation relation (child marriage per UNICEF definition), before the age of 18. Over 4% of all underage girls in the UK were teenage mothers.

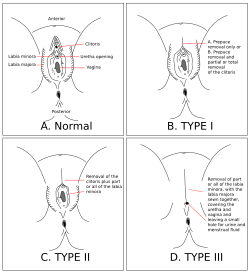

In July 2014, the United Kingdom hosted its first global Girl Summit; the goal of the Summit was to increase efforts to end child, early, and forced marriage and female genital mutilation within a generation.

Oceania

The Marquesas Islands have been noted for their sexual culture. Many sexual activities seen as taboo in Western cultures are viewed appropriate by the native culture. One of these differences is that children are introduced and educated to sex at a very young age. Contact with Western societies has changed many of these customs, so research into their pre-Western social history has to be done by reading antique writings. Children slept in the same room as their parents and were able to witness their parents while they had sex. Intercourse simulation became real penetration as soon as boys were physically able. Adults found simulation of sex by children to be funny. As children approached 11 attitudes shifted toward girls. When a child reaches adulthood, they are educated on sexual techniques by a much older adult.Yuri Lisyansky in his memoirs reports that:

The next day, as soon as it was light, we were surrounded by a still greater multitude of these people. There were now a hundred females at least; and they practised all the arts of lewd expression and gesture, to gain admission on board. It was with difficulty I could get my crew to obey the orders I had given on this subject. Amongst these females were some not more than ten years of age. But youth, it seems, is here no test of innocence; these infants, as I may call them, rivalled their mothers in the wantonness of their motions and the arts of allurement.Adam Johann von Krusenstern in his book about the same expedition as Yuri's, reports that a father brought a 10- to 12-year-old girl on his ship, and she had sex with the crew. According to the book of Charles Pierre Claret de Fleurieu and Étienne Marchand, 8-year-old girls had sex and other unnatural acts in public.

Consequences of child marriage

Birth rates per 1,000 women aged 15–19 years, worldwide.

Child marriage has lasting consequences on girls that last well beyond adolescence. Women married in their teens or earlier struggle with the health effects of getting pregnant at a young age and often with little spacing between children. Early marriages followed by teen pregnancy also significantly increase birth complications and social isolation. In poor countries, early pregnancy limits or can even eliminate a woman's education options, affecting her economic independence. Girls in child marriages are more likely to suffer from domestic violence, child sexual abuse, and marital rape.

Health

Child marriage threatens the health and life of girls. Complications from pregnancy and childbirth are the main cause of death among adolescent girls below age 19 in developing countries. Girls aged 15 to 19 are twice as likely to die in childbirth as women in their 20s, and girls under the age of 15 are five to seven times more likely to die during childbirth. These consequences are due largely to girls' physical immaturity where the pelvis and birth canal are not fully developed. Teen pregnancy, particularly below age 15, increases risk of developing obstetric fistula, since their smaller pelvises make them prone to obstructed labor. Girls who give birth before the age of 15 have an 88% risk of developing fistula. Fistula leaves its victims with urine or fecal incontinence that causes lifelong complications with infection and pain. Unless surgically repaired, obstetric fistulas can cause years of permanent disability, shame to mothers, and can result in being shunned by the community. Married girls also have a higher risk of sexually transmitted diseases, cervical cancer, and malaria than non-married peers or girls who marry in their 20s.Child marriage not only threatens the mother’s health, it also threatens the lives of offspring. Mothers under the age of 18 years have 35 to 55% increased risk of delivering pre-term or having a low birth weight baby than a mother who is 19 years old. In addition, infant mortality rates are 60% higher when the mother is under 18 years old. Infants born to child mothers tend to have weaker immune systems and face a heightened risk of malnutrition.

Prevalence of child marriage may also be associated with higher rates of population growth, more cases of children left orphaned, and the accelerated spread of disease.

Illiteracy and poverty

Child marriage often ends a girl's education, particularly in impoverished countries where child marriages are common. In addition, uneducated girls are more at risk for child marriage. Girls that have only a primary education are twice as likely to marry before age 18 than those with a secondary or higher education, and girls with no education are three times more likely to marry before age 18 than those with a secondary education. Early marriage impedes a young girl’s ability to continue with her education as most drop out of school following marriage to focus their attention on domestic duties and having or raising children. Girls may be taken out of school years before they are married due to family or community beliefs that allocating resources for girls' education is unnecessary given that her primary roles will be that of wife and mother. Without education, girls and adult women have fewer opportunities to earn an income and financially provide for themselves and their children. This makes girls more vulnerable to persistent poverty if their spouses die, abandon, or divorce them. Given that girls in child marriages are often significantly younger than their husbands, they become widowed earlier in life and may face associated economic and social challenges for a greater portion of their life than women who marry later.Domestic violence

Married teenage girls with low levels of education suffer greater risk of social isolation and domestic violence than more educated women who marry as adults. Following marriage, girls frequently relocate to their husband’s home and take on the domestic role of being a wife, which often involves relocating to another village or area. This transition may result in a young girl dropping out of school, moving away from her family and friends, and a loss of the social support that she once had. A husband's family may also have higher expectations for the girl's submissiveness to her husband and his family because of her youth. This sense of isolation from a support system can have severe mental health implications including depression.Large age gaps between the child and her spouse makes her more vulnerable to domestic violence and marital rape. Girls who marry as children face severe and life-threatening marital violence at higher rates. Husbands in child marriages are often more than ten years older than their wives. This can increase the power and control a husband has over his wife and contribute to prevalence of spousal violence. Early marriage places young girls in a vulnerable situation of being completely dependent on her husband. Domestic and sexual violence from their husbands has lifelong, devastating mental health consequences for young girls because they are at a formative stage of psychological development. These mental health consequences of spousal violence can include depression and suicidal thoughts. Child brides, particularly in situations such as vani, also face social isolation, emotional abuse and discrimination in the homes of their husbands and in-laws.

Women's rights

The United Nations, through a series of conventions has declared child marriage a violation of human rights. The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination of Women (‘CEDAW’), the Committee on the Rights of the Child (‘CRC’), and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights form the international standard against child marriage. Child marriages impact violates a range of women's interconnected rights such as equality on grounds of sex and age, to receive the highest attainable standard of health, to be free from slavery, access to education, freedom of movement, freedom from violence, reproductive rights, and the right to consensual marriage. The consequence of these violations impact woman, her children and the broader society.Development

High rates of child marriage negatively impact countries' economic development because of early marriages' impact on girls' education and labor market participation. Some researchers and activists note that high rates of child marriage prevent significant progress toward each of the eight Millennium Development Goals and global efforts to reduce poverty due to its effects on educational attainment, economic and political participation, and health.A UNICEF Nepal issued report noted that child marriage impacts Nepal's development due to loss of productivity, poverty, and health effects. Using Nepal Multi-Indicator Survey data, its researchers estimate that all girls delaying marriage until age 20 and after would increase cash flow among Nepali women in an amount equal to 3.87% of the country's GDP. Their estimates considered decreased education and employment among girls in child marriages in addition to low rates of education and high rates of poverty among children from child marriages.

International initiatives to prevent child marriage

In December 2011 a resolution adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (A/RES/66/170) designated October 11 as the International Day of the Girl Child. On October 11, 2012 the first International Day of the Girl Child was held, the theme of which was ending child marriage.In 2013 the first United Nations Human Rights Council resolution against child, early, and forced marriages was adopted; it recognizes child marriage as a human rights violation and pledges to eliminate the practice as part of the U.N.'s post-2015 global development agenda.

In 2014 the UN's Commission on the Status of Women issued a document in which they agreed, among other things, to eliminate child marriage.

The World Health Organization recommends increased educational attainment among girls, increased enforcement structures for existing minimum marriage age laws, and informing parents in practicing communities of the risks associated as primary methods to prevent child marriages.

Programs to prevent child marriage have taken several different approaches. Various initiatives have aimed to empower young girls, educate parents on the associated risks, change community perceptions, support girls' education, and provide economic opportunities for girls and their families through means other than marriage. A survey of a variety of prevention programs found that initiatives were most effect when they combined efforts to address financial constraints, education, and limited employment of women.

Girls in families participating in an unconditional cash transfer program in Malawi aimed at incentivizing girls' education got married and had children later than their peers who had not participated in the program. The program's effects on rates of child marriage were greater for unconditional cast transfer programs than those with conditions. Evaluators believe this demonstrated that the economic needs of the family heavily influenced the appeal of child marriage in this community. Therefore, reducing financial pressures on the family decreased the economic motivations to marry daughters off at a young age.

The Haryana state government in India operated a program in which poor families were given a financial incentive if they kept their daughters in school and unmarried until age 18. Girls in families who were eligible for the program were less likely to be married before age 18 than their peers.

A similar program was operated in 2004 by the Population Council and the regional government in Ethiopia's rural Amhara region. Families received cash if their daughters remained in school and unmarried during the two years of the program. They also instituted mentorship programs, livelihood training, community conversations about girls' education and child marriage, and gave school supplies for girls. After the two-year program, girls in families eligible for the program were three times more likely to be in school and one tenth as likely to be married compared to their peers.

Other programs have addressed child marriage less directly through a variety of programming related to girls' empowerment, education, sexual and reproductive health, financial literacy, life skills, communication skills, and community mobilization.

In 2018, UN Women announced that Jaha Dukureh would serve as Goodwill Ambassador in Africa to help organize to prevent child marriage.

Tipping point analysis

Researchers at the International Center for Research on Women found that in some communities rates of child marriage increase significantly when girls are a particular age. This "tipping point", or age at which rates of marriage increase dramatically, may occur years before the median age of marriage. Therefore, the researchers argue prevention programs should focus their programming on girls who are pre-tipping point age rather than only girls who are married before they reach the median age for marriage.Prevalence data

Two sets of prevalence data for a sample of countries are provided in the table below. Column one lists the percentage of women aged 20–24 who were married or in union before the age of 18; this data, from International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) and UNICEF, is dated between 2006 and 2017. Column two lists the percentage of females aged 15-19 who were ever married; this data, from the UN, is dated between 1995 and 2002.| Country | % girls married before 18 ICRW-UNICEF data (Year of data) |

% females married aged 15-19 UN data (year of data) |

|---|---|---|

| 76 (2012) | 62 (1998) | |

| 67 (2014-2015) | 49 (1996) | |

| 68 (2010) | 42 (1995) | |

| 59 (2014) | 48 (2000) | |

| 52 (2015) | 50 (1996) | |

| 51 (2016) | 46 (1996) | |

| 42 (2015) | 37 (2000) | |

| 48 (2011) | 47 (1997) | |

| 41 (2012-2013) | 34 (1997) | |

| 39 (2013) | 47 (1992) | |

| 52 (2010) | 35 (1999) | |

| 27 (2015-2016) | 30 (1999) | |

| 45 (2006) | 38 | |

| 35 (2011–2012) | 32 (1998) | |

| 31 (2013–2014) | 24 (2002) | |

| 41 (2010) | 38 (1995) | |

| 40 (2011) | 32 (2001) | |

| 40 (2016) | 30 (2000) | |

| 40 (2016) | 40 (2001) | |

| 36 (2014) | 29 (1996) | |

| 35 (2015) | 29 | |

| 52 (2010) | - | |

| 44 (2016-2017) | 28 (1999) |