| Physical map of Northern Asia. | ||

|---|---|---|

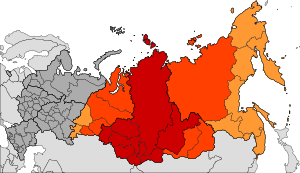

Siberia within the Russian Federation: North Asia in light red, political Siberian Federal District in dark red

Including the Russian Far East, the population of Siberia numbers just above 40 million people. As a result of the 17th to 19th century Russian conquest of Siberia and the subsequent population movements during the Soviet era, the demographics of Siberia today is dominated by native speakers of Russian. There remain a considerable number of indigenous groups, between them accounting for below 10% of total Siberian population (About 4,500,000), which are also genetically related to Indigenous Peoples of the Americas.

History

Koryak men at the ceremony of starting the New Fire

In Kamchatka the Itelmens' uprisings against Russian rule in 1706, 1731, and 1741, were crushed. During the first uprising the Itelmen were armed with only stone weapons, but in later uprisings they used gunpowder weapons. The Russian Cossacks faced tougher resistance from the Koryaks, who revolted with bows and guns from 1745 to 1756, and were even forced to give up in their attempts to wipe out the Chukchi in 1729, 1730-1, and 1744-7. After the Russian defeat in 1729 at Chukchi hands, the Russian commander Major Pavlutskiy was responsible for the Russian war against the Chukchi and the mass slaughters and enslavement of Chukchi women and children in 1730-31, but his cruelty only made the Chukchis fight more fiercely. A war against the Chukchis and Koryaks was ordered by Empress Elizabeth in 1742 to totally expel them from their native lands and erase their culture through war. The command was that the natives be "totally extirpated" with Pavlutskiy leading again in this war from 1744-47 in which he led to the Cossacks "with the help of Almighty God and to the good fortune of Her Imperial Highness", to slaughter the Chukchi men and enslave their women and children as booty. However this phase of the war came to an inconclusive end, when the Chukchi forced them to give up by killing Pavlutskiy and decapitating him.

The Russians were also launching wars and slaughters against the Koryaks in 1744 and 1753-4. After the Russians tried to force the natives to convert to Christianity, the different native peoples like the Koryaks, Chukchis, Itelmens, and Yukaghirs all united to drive the Russians out of their land in the 1740s, culminating in the assault on Nizhnekamchatsk fort in 1746. Kamchatka today is European in demographics and culture with only 2.5% of it being native, around 10,000 from a previous number of 150,000, due to infectious diseases, such as smallpox, mass suicide and the mass slaughters by the Cossacks after its annexation in 1697 of the Itelmen and Koryaks throughout the first decades of Russian rule. The genocide by the Russian Cossacks devastated the native peoples of Kamchatka and exterminated much of their population. In addition to committing genocide the Cossacks also devastated the wildlife by slaughtering massive numbers of animals for fur. 90% of the Kamchadals and half of the Vogules were killed from the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries and the rapid genocide of the indigenous population led to entire ethnic groups being entirely wiped out, with around 12 exterminated groups which could be named by Nikolai Iadrintsev as of 1882. Much of the slaughter was brought on by the fur trade.

President of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) Yegor Borisov in 2010

In the 17th century, indigenous peoples of the Amur region were attacked and colonized by Russians who came to be known as "red-beards". The Russian Cossacks were named luocha (羅剎), rakshasa by Amur natives, after demons found in Buddhist mythology. They feared the invaders as they ruthlessly colonized the Amur tribes, invaders who were subjects of the Qing dynasty during the Sino–Russian border conflicts.

The Aleuts in the Aleutians in Alaska were subjected to genocide and slavery for the first 20 years of Russian rule, with the Aleut women and children captured and Aleut men slaughtered. Then Catherine the Great issued various instructions to prevail humanity in the treatment with indigenous peoples.

The regionalist oblastniki was, in the 19th century, among the Russians in Siberia who acknowledged that the natives were subjected to violence of almost genocidal proportions by the Russian colonization. They claimed that they would rectify the situation with their proposed regionalist policies. The colonizers used slaughter, alcoholism and disease to bring the natives under their control, some small nomadic groups essentially disappeared, and much of the evidence of their obliteration has itself been destroyed, with only a few artifacts documenting their presence remaining in Russian museums and collections.

In 1918-1921 there was a violent revolutionary upheaval in Siberia. Russian Cossacks under Captain Grigori Semionov established themselves as warlords by crushing the indigenous peoples who resisted colonization. The Russian colonization of Siberia and conquest of its indigenous peoples has been compared to European colonization in the United States and its natives, with similar negative impacts on the natives and the appropriation of their land. However Siberian experience was very different, as settlement was not resulted to dramatic native depopulation. The Slavic Russians outnumber all of the native peoples in Siberia and its cities except in the Republic of Tuva and Sakha Republic, with the Slavic Russians making up the majority in the Buriat Republic and Altai Republics, outnumbering the Buriat and Altai natives. The Buriat make up only 29% of their own Republic, and Altai is only one-third, and the Chukchi, Evenk, Khanti, Mansi, and Nenets are outnumbered by non-natives by 90% of the population. The Czars and Soviets enacted policies to force natives to change their way of life, while rewarding ethnic Russians with the natives’ reindeer herds and wild game they had confiscated. The reindeer herds have been mismanaged to the point of extinction.

Overview

Nenets child

Painting of Chukchi couple

- Uralic

- Yukaghir (nearly extinct)

- Turkic

- Yakuts (456,288 speakers)

- Dolgans (population: 7,261; speakers: 4,865)

- Tuvans (population: 243,442; speakers: 242,754)

- Tofa (population: 837; speakers: 378)

- Khakas (population: 75,622; speakers: 52,217)

- Shors (population: 13,975; speakers: 6,210)

- Siberian Tatars (populations: 6,779)

- Chulyms (population: 656; speakers: 270)

- Altay (some 70,000 speakers)

- Mongolic (some 400,000 speakers)

- Tungusic (some 80,000 speakers)

- Ob-Yeniseian

- Ket (population: 1600; some 210 speakers)

- Chukotko-Kamchatkan (some 25,000 speakers)

- Nivkh (some 200 speakers)

- Eskimo–Aleut (some 2,000 speakers)

- Uralic

- Altaic

- Yeniseian branch of the Dené–Yeniseian languages

- Paleosiberian ("other")

Uralic group

Khanty and Mansi

Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobyanin is a member of the Mansi people

The Khanty (obsolete: Ostyaks) and Mansi (obsolete: Voguls) live in Khanty–Mansi Autonomous Okrug, a region historically known as "Yugra" in Russia south-east of Komi. By 2013, oil and gas companies had already devastated much of the Khanty tribes' lands. In 2014 the Khanty-Mansiisk regional parliament continued to weaken legislation that had previously protected Khanty and Mansi communities. Tribes' permission was required before oil and gas companies could enter their land. The semi-nomadic reindeer herding people, the Izhemtsi in the Komi republic of Russia, just west of the Ural mountains, had already rejected the Russian oil-giant LUKOIL takeover of their land for oil exploration and drilling.

Samoyeds

Selkups

- Northern Samoyedic peoples

- Southern Samoyedic peoples

Yukaghir

The Yukaghir (self-designation: одул odul, деткиль detkil) are people in East Siberia, living in the basin of the Kolyma River. The Tundra Yukaghirs live in the Lower Kolyma region in the Sakha Republic; the Taiga Yukagirs in the Upper Kolyma region in the Sakha Republic and in Srednekansky District of Magadan Oblast. By the time of Russian colonization in the 17th century, the Yukagir tribal groups (Chuvans, Khodyns, Anauls, etc.) occupied territories from the Lena River to the mouth of the Anadyr River. The number of the Yukagirs decreased between the 17th and 19th centuries due to epidemics, internecine wars and Tsarist colonial policy. Some of the Yukagirs have assimilated with the Yakuts, Evens, and Russians. Currently Yukagir live in the Yakut-Sakha Republic and the Chukotka Autonomous region of the Russian Federation. According to the 2002 Census, their total number was 1,509 people, up from 1,112 recorded in the 1989 Census.Mongolic group

The Buryats number approximately 436,000, which makes them the largest ethnic minority group in Siberia. They are mainly concentrated in their homeland, the Buryat Republic, a federal subject of Russia. They are the northernmost major Mongol group.

Buryats share many customs with their Mongolian cousins, including nomadic herding and erecting huts for shelter. Today, the majority of Buryats live in and around Ulan Ude, the capital of the republic, although many live more traditionally in the countryside. Their language is called Buryat.

Turkic people

The most important examples for Shamanism in Siberia are Yakuts, Dolgans and Tuvans.

Most Siberian Tatars are Sunni Muslims.

Tungusic group

The Evenks live in the Evenk Autonomous Okrug of Russia.The Udege, Ulchs, Evens, and Nanai (also known as Hezhen) are also indigenous peoples of Siberia, and are known to share genetic affinity to Indigenous Peoples of the Americas.

"Paleosiberian" group

Four small language families and isolates, not known to have any linguistic relationship to each other, compose the Paleo-Siberian languages:- 1. The Chukotko-Kamchatkan family, sometimes known as Luoravetlan, includes Chukchi and its close relatives, Koryak, Alutor and Kerek. Itelmen, also known as Kamchadal, is also distantly related. Chukchi, Koryak and Alutor are spoken in easternmost Siberia by communities numbering in the dozens (Alutor) to thousands (Chukchi). Kerek is now extinct, and Itelmen is now spoken by fewer than 10 people, mostly elderly, on the west coast of the Kamchatka Peninsula.

- 2. Yukaghir is spoken in two mutually unintelligible varieties in the lower Kolyma and Indigirka valleys. Other languages, including Chuvantsy, spoken further inland and further east, are now extinct. Yukaghir is held by some to be related to the Uralic languages.

- 3. Ket is the last survivor of a small language family on the middle Yenisei and its tributaries. It has recently been claimed [1] to be related to the Na-Dene languages of North America, though this hypothesis has met with mixed reviews among historical linguists. In the past, attempts have been made to relate it to Sino-Tibetan, North Caucasian, and Burushaski.

- 4. Nivkh is spoken in the lower Amur basin and on the northern half of Sakhalin island. It has a recent modern literature and the Nivkhs have experienced a turbulent history in the last century.

Relationship to Indigenous peoples of the Americas

Indigenous Siberian Shaman at Kranoyarsk Regional Museum, Russia

Paleo-Indians from modern day Siberia are thought to have crossed into the Americas across the Beringia land bridge between 40,000-13,000 years ago. A Georgetown University study has suggested that migration across the land bridge resulted in the similarity of the North American Na-Dene languages and Siberian Yeniseian languages, uniting as the Dené–Yeniseian languages family.

Analysis of genetic markers has also been used to link the two groups of indigenous peoples. Studies focused on looking at markers on the Y chromosome, which is always inherited by sons from their fathers. Haplogroup Q is a unique mutation shared among most indigenous peoples of the Americas. Studies have found that 93.8% of Siberia's Ket people's and 66.4% of Siberia's Selkup people's possess the mutation. The principal-component analysis suggests a close genetic relatedness between some North American Amerindians (the Chipewyan and the Cheyenne) and certain populations of central/southern Siberia (particularly the Kets, Yakuts, Selkups, and Altays), at the resolution of major Y-chromosome haplogroups. This pattern agrees with the distribution of mtDNA haplogroup X, which is found in North America, is absent from eastern Siberia, but is present in the Altais of southern central Siberia. The genetic evidence points to a strong connection between Amerindians being related to indigenous people of the Altai Mountains region of Siberia.

Culture and customs

Laminar armour of hardened leather enforced by wood and bones worn by the Chukchi, Aleut, and Chugach (Alutiiq)

Late lamellar armour worn by indigenous peoples of Siberia

Indigenous Siberian Canoe at Krasnoyark Regional Museum, Russia

Indigenous Siberian Musical Instrument used with Throat Singing, at Krasnoyarsk Regional Museum, Russia

Literature

- Rubcova, E.S.: Materials on the Language and Folklore of the Eskimoes, Vol. I, Chaplino Dialect. Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moskva * Leningrad, 1954

- Menovščikov, G. A. (= Г. А. Меновщиков) (1968). "Popular Conceptions, Religious Beliefs and Rites of the Asiatic Eskimoes". In Diószegi, Vilmos. Popular beliefs and folklore tradition in Siberia. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Barüske, Heinz: Eskimo Märchen. Eugen Diederichs Verlag, Düsseldorf and Köln, 1969.

- Merkur, Daniel: Becoming Half Hidden / Shamanism and Initiation Among the Inuit. Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis / Stockholm Studies in Comparative Religion. Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm, 1985.

- Kleivan, I. and Sonne, B.: Eskimos / Greenland and Canada. (Series: Iconography of religions, section VIII /Arctic Peoples/, fascicle 2). Institute of Religious Iconography • State University Groningen. E.J. Brill, Leiden (The Netherland), 1985. ISBN 90-04-07160-1.