Military science is the study of military processes, institutions, and behavior, along with the study of warfare, and the theory and application of organized coercive force. It is mainly focused on theory, method, and practice of producing military capability in a manner consistent with national defense policy. Military science serves to identify the strategic, political, economic, psychological, social, operational, technological, and tactical elements necessary to sustain relative advantage of military force; and to increase the likelihood and favorable outcomes of victory in peace or during a war. Military scientists include theorists, researchers, experimental scientists, applied scientists, designers, engineers, test technicians, and other military personnel.

Military personnel obtain weapons, equipment, and training to achieve specific strategic goals. Military science is also used to establish enemy capability as part of technical intelligence.

In military history, military science had been used during the period of Industrial Revolution as a general term to refer to all matters of military theory and technology application as a single academic discipline, including that of the deployment and employment of troops in peacetime or in battle.

In military education, military science is often the name of the department in the education institution that administers officer candidate education. However, this education usually focuses on the officer leadership training and basic information about employment of military theories, concepts, methods and systems, and graduates are not military scientists on completion of studies, but rather junior military officers.

History

CLASS

IN TELEPHONY: ENLISTED MEN, U. S. ARMY. The telephone in modern

warfare has robbed battle of much of its picturesqueness, romance, and

glamor; as the dashing dispatch rider

on his foam-flecked steed is antiquated. A message sent by telephone

annihilates space and time, whereas the dispatch rider would, in most

cases, be annihilated by shrapnel. Published 1917.

Even until the Second World War, military science was written in English starting with capital letters, and was thought of as an academic discipline alongside Physics, Philosophy and the Medical Science. In part this was due to the general mystique that accompanied education in a World where as late as the 1880s 75% of the European population was illiterate. The ability by the officers to make complex calculations required for the equally complex "evolutions" of the troop movements in linear warfare that increasingly dominated the Renaissance and later history, and the introduction of the gunpowder weapons into the equation of warfare only added to the veritable arcana of building fortifications as it seemed to the average individual.

Until the early 19th century, one observer, a British veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, Major John Mitchell thought that it seemed nothing much had changed from the application of force on a battlefield since the days of the Greeks. He suggested that this was primarily so because as Clausewitz suggested, "unlike in any other science or art, in war the object reacts".

Until this time, and even after the Franco-Prussian War, military science continued to be divided between the formal thinking of officers brought up in the "shadow" of Napoleonic Wars and younger officers like Ardant du Picq who tended to view fighting performance as rooted in the individual's and group psychology and suggested detailed analysis of this. This set in motion the eventual fascination of the military organisations with application of quantitative and qualitative research to their theories of combat; the attempt to translate military thinking as philosophic concepts into concrete methods of combat.

Military implements, the supply of an army, its organization, tactics, and discipline, have constituted the elements of military science in all ages; but improvement in weapons and accoutrements appears to lead and control all the rest.

The breakthrough of sorts made by Clausewitz in suggesting eight principles on which such methods can be based, in Europe, for the first time presented an opportunity to largely remove the element of chance and error from command decision making process. At this time emphasis was made on the Topography (including Trigonometry), Military art (Military science), Military history, Organisation of the Army in the field, Artillery and Science of Projectiles, Field fortifications and Permanent fortifications, Military legislation, Military administration and Manoeuvres.

The military science on which the model of German combat operations was built for the First World War remained largely unaltered from the Napoleonic model, but took into the consideration the vast improvements in the firepower and the ability to conduct "great battles of annihilation" through rapid concentration of force, strategic mobility, and the maintenance of the strategic offensive better known as the Cult of the offensive. The key to this, and other modes of thinking about war remained analysis of military history and attempts to derive tangible lessons that could be replicated again with equal success on another battlefield as a sort of bloody laboratory of military science. Few were bloodier than the fields of the Western Front between 1914 and 1918. Fascinatingly the man who probably understood Clausewitz better than most, Marshal Foch would initially participate in events that nearly destroyed the French Army.

It is not however true to say that military theorists and commanders were suffering from some collective case of stupidity; quite the opposite is true. Their analysis of military history convinced them that decisive and aggressive strategic offensive was the only doctrine of victory, and feared that overemphasis of firepower, and the resultant dependence on entrenchment would make this all but impossible, and leading to the battlefield stagnant in advantages of the defensive position, destroying troop morale and willingness to fight. Because only the offensive could bring victory, lack of it, and not the firepower, was blamed for the defeat of the Imperial Russian Army in the Russo-Japanese War. Foch thought that "In strategy as well as in tactics one attacks".

In many ways military science was born as a result of the experiences of the Great War. "Military implements" had changed armies beyond recognition with cavalry to virtually disappear in the next 20 years. The "supply of an army" would become a science of logistics in the wake of massive armies, operations and troops that could fire ammunition faster than it could be produced, for the first time using vehicles that used the combustion engine, a watershed of change. Military "organisation" would no longer be that of the linear warfare, but assault teams, and battalions that were becoming multi-skilled with introduction of machine gun and mortar, and for the first time forcing military commanders to think not only in terms of rank and file, but force structure.

Tactics changed too, with infantry for the first time segregated from the horse-mounted troops, and required to cooperate with tanks, aircraft and new artillery tactics. Perception of military discipline too had changed. Morale, despite strict disciplinarian attitudes, had cracked in all armies during the war, but best performing troops were found to be those where emphasis on discipline had been replaced with display of personal initiative and group cohesiveness such as that found in the Australian Corps during the Hundred Days Offensive. The military sciences' analysis of military history that had failed European commanders was about to give way to a new military science, less conspicuous in appearance, but more aligned to the processes of science of testing and experimentation, the scientific method, and forever "wed" to the idea of the superiority of technology on the battlefield.

Currently military science still means many things to different organisations. In the United Kingdom and much of the European Union the approach is to relate it closely to the civilian application and understanding. The Defence Scientific Advisory Council sees this in terms of the fields of science, engineering, technology and analysis (SETA) that includes broad strategic issues, priorities and policies related to developing military capabilities. In Europe, for example Belgium's Royal Military Academy, military science remains an academic discipline, and is studied alongside Social Sciences, including such subjects as Humanitarian law. The United States Department of Defense defines military science in terms of specific systems and operational requirements, and include among other areas civil defense and force structure.

Employment of military skills

In the first instance military science is concerned with who will participate in military operations, and what sets of skills and knowledge they will require to do so effectively and somewhat ingeniously.Military organization

Develops optimal methods for the administration and organization of military units, as well as the military as a whole. In addition, this area studies other associated aspects as mobilization/demobilization, and military government for areas recently conquered (or liberated) from enemy control.Force structuring

Force structuring is the method by which personnel and the weapons and equipment they use are organized and trained for military operations, including combat. Development of force structure in any country is based on strategic, operational, and tactical needs of the national defense policy, the identified threats to the country, and the technological capabilities of the threats and the armed forces.Force structure development is guided by doctrinal considerations of strategic, operational and tactical deployment and employment of formations and units to territories, areas and zones where they are expected to perform their missions and tasks. Force structuring applies to all Armed Services, but not to their supporting organisations such as those used for defense science research activities.

In the United States force structure is guided by the table of organization and equipment (TOE or TO&E). The TOE is a document published by the U.S. Department of Defense which prescribes the organization, manning, and equipage of units from divisional size and down, but also including the headquarters of Corps and Armies.

Force structuring also provides information on the mission and capabilities of specific units, as well as the unit's current status in terms of posture and readiness. A general TOE is applicable to a type of unit (for instance, infantry) rather than a specific unit (the 3rd Infantry Division). In this way, all units of the same branch (such as Infantry) follow the same structural guidelines which allows for more efficient financing, training, and employment of like units operationally.

Military education and training

Studies the methodology and practices involved in training soldiers, NCOs (non-commissioned officers, i.e. sergeants and corporals), and officers. It also extends this to training small and large units, both individually and in concert with one another for both the regular and reserve organizations. Military training, especially for officers, also concerns itself with general education and political indoctrination of the armed forces.Military concepts and methods

Much of capability development depends on the concepts which guide use of the armed forces and their weapons and equipment, and the methods employed in any given theatre of war or combat environment.Military history

Military activity has been a constant process over thousands of years, and the essential tactics, strategy, and goals of military operations have been unchanging throughout history. As an example, one notable maneuver is the double envelopment, considered to be the consummate military maneuver, first executed by Hannibal at the Battle of Cannae in 216 BCE, and later by Khalid ibn al-Walid at the Battle of Walaja in 633 CE.Via the study of history, the military seeks to avoid past mistakes, and improve upon its current performance by instilling an ability in commanders to perceive historical parallels during battle, so as to capitalize on the lessons learned. The main areas military history includes are the history of wars, battles, and combats, history of the military art, and history of each specific military service.

Military strategy and doctrines

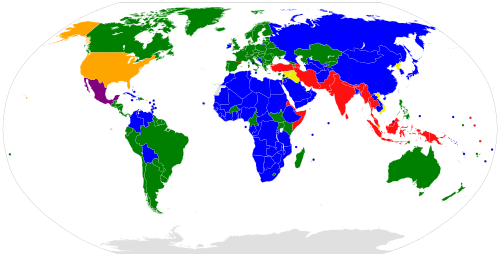

Military strategy is in many ways the centerpiece of military science. It studies the specifics of planning for, and engaging in combat, and attempts to reduce the many factors to a set of principles that govern all interactions of the field of battle. In Europe these principles were first defined by Clausewitz in his Principles of War. As such, it directs the planning and execution of battles, operations, and wars as a whole. Two major systems prevail on the planet today. Broadly speaking, these may be described as the "Western" system, and the "Russian" system. Each system reflects and supports strengths and weakness in the underlying society.

Modern Western military art is composed primarily of an amalgam of French, German, British, and American systems. The Russian system borrows from these systems as well, either through study, or personal observation in the form of invasion (Napoleon's War of 1812, and The Great Patriotic War), and form a unique product suited for the conditions practitioners of this system will encounter. The system that is produced by the analysis provided by Military Art is known as doctrine.

Western military doctrine relies heavily on technology, the use of a well-trained and empowered NCO cadre, and superior information processing and dissemination to provide a level of battlefield awareness that opponents cannot match. Its advantages are extreme flexibility, extreme lethality, and a focus on removing an opponent's C3I (command, communications, control, and intelligence) to paralyze and incapacitate rather than destroying their combat power directly (hopefully saving lives in the process). Its drawbacks are high expense, a reliance on difficult-to-replace personnel, an enormous logistic train, and a difficulty in operating without high technology assets if depleted or destroyed.

Soviet military doctrine (and its descendants, in CIS countries) relies heavily on masses of machinery and troops, a highly educated (albeit very small) officer corps, and pre-planned missions. Its advantages are that it does not require well educated troops, does not require a large logistic train, is under tight central control, and does not rely on a sophisticated C3I system after the initiation of a course of action. Its disadvantages are inflexibility, a reliance on the shock effect of mass (with a resulting high cost in lives and material), and overall inability to exploit unexpected success or respond to unexpected loss.

Chinese military doctrine is currently in a state of flux as the People's Liberation Army is evaluating military trends of relevance to China. Chinese military doctrine is influenced by a number of sources including an indigenous classical military tradition characterized by strategists such as Sun Tzu, Western and Soviet influences, as well as indigenous modern strategists such as Mao Zedong. One distinctive characteristic of Chinese military science is that it places emphasis on the relationship between the military and society as well as viewing military force as merely one part of an overarching grand strategy.

Each system trains its officer corps in its philosophy regarding military art. The differences in content and emphasis are illustrative. The United States Army principles of war are defined in the U.S. Army Field Manual FM 100–5. The Canadian Forces principles of war/military science are defined by Land Forces Doctrine and Training System (LFDTS) to focus on principles of command, principles of war, operational art and campaign planning, and scientific principles.

Russian Federation armed forces derive their principles of war predominantly from those developed during the existence of the Soviet Union. These, although based significantly on the Second World War experience in conventional war fighting, have been substantially modified since the introduction of the nuclear arms into strategic considerations. The Soviet–Afghan War and the First and Second Chechen Wars further modified the principles that Soviet theorists had divided into the operational art and tactics. The very scientific approach to military science thinking in the Soviet union had been perceived as overly rigid at the tactical level, and had affected the training in the Russian Federation's much reduced forces to instil greater professionalism and initiative in the forces.

The military principles of war of the People's Liberation Army were loosely based on those of the Soviet Union until the 1980s when a significant shift begun to be seen in a more regionally-aware, and geographically-specific strategic, operational and tactical thinking in all services. The PLA is currently influenced by three doctrinal schools which both conflict and complement each other: the People's war, the Regional war, and the Revolution in military affairs that led to substantial increase in the defense spending and rate of technological modernisation of the forces.

The differences in the specifics of Military art notwithstanding, Military science strives to provide an integrated picture of the chaos of battle, and illuminate basic insights that apply to all combatants, not just those who agree with your formulation of the principles.

Military geography

Military geography encompasses much more than simple protestations to take the high ground. Military geography studies the obvious, the geography of theatres of war, but also the additional characteristics of politics, economics, and other natural features of locations of likely conflict (the political "landscape", for example). As an example, the Soviet–Afghan War was predicated on the ability of the Soviet Union to not only successfully invade Afghanistan, but also to militarily and politically flank the Islamic Republic of Iran simultaneously.Military systems

How effectively and efficiently militaries accomplish their operations, missions and tasks is closely related not only to the methods they use, but the equipment and weapons they use.Military intelligence

Military intelligence supports the combat commanders' decision making process by providing intelligence analysis of available data from a wide range of sources. To provide that informed analysis the commanders information requirements are identified and input to a process of gathering, analysis, protection, and dissemination of information about the operational environment, hostile, friendly and neutral forces and the civilian population in an area of combat operations, and broader area of interest. Intelligence activities are conducted at all levels from tactical to strategic, in peacetime, the period of transition to war, and during the war.Most militaries maintain a military intelligence capability to provide analytical and information collection personnel in both specialist units and from other arms and services. Personnel selected for intelligence duties, whether specialist intelligence officers and enlisted soldiers or non-specialist assigned to intelligence may be selected for their analytical abilities and intelligence before receiving formal training.

Military intelligence serves to identify the threat, and provide information on understanding best methods and weapons to use in deterring or defeating it.

Military logistics

The art and science of planning and carrying out the movement and maintenance of military forces. In its most comprehensive sense, it is those aspects or military operations that deal with the design, development, acquisition, storage, distribution, maintenance, evacuation, and disposition of material; the movement, evacuation, and hospitalization of personnel; the acquisition or construction, maintenance, operation, and disposition of facilities; and the acquisition or furnishing of services.Military technology and equipment

Military technology is not just the study of various technologies and applicable physical sciences used to increase military power. It may also extend to the study of production methods of military equipment, and ways to improve performance and reduce material and/or technological requirements for its production. An example is the effort expended by Nazi Germany to produce artificial rubbers and fuels to reduce or eliminate their dependence on imported POL (petroleum, oil, and lubricants) and rubber supplies.Military technology is unique only in its application, not in its use of basic scientific and technological achievements. Because of the uniqueness of use, military technological studies strive to incorporate evolutionary, as well as the rare revolutionary technologies, into their proper place of military application.