Human genetic clustering is the degree to which human genetic variation can be partitioned into a small number of groups or clusters. A leading method of analysis uses mathematical cluster analysis of the degree of similarity of genetic data between individuals and groups in order to infer population structures and assign individuals to hypothesized ancestral groups. A similar analysis can be done using principal components analysis, and several recent studies deploy both methods.

Analysis of genetic clustering examines the degree to which

regional groups differ genetically, the categorization of individuals

into clusters, and what can be learned about human ancestry from this

data. There is broad scientific agreement that a relatively small

fraction of human genetic variation occurs between populations,

continents, or clusters. Researchers of genetic clustering differ,

however, on whether genetic variation is principally clinal or whether clusters inferred mathematically are important and scientifically useful.

Analysis of human genetic variation

Quantifying variation

One of the underlying questions regarding the distribution of human genetic diversity is related to the degree to which genes are shared between the observed clusters. It has been observed repeatedly that the majority of variation observed in the global human population is found within populations. This variation is usually calculated using Sewall Wright's fixation index (FST), which is an estimate of between to within group variation. The degree of human genetic variation is a little different depending upon the gene type studied, but in general it is common to claim that ~85% of genetic variation is found within groups, ~6–10% between groups within the same continent and ~6–10% is found between continental groups. Ryan Brown and George Armelagos described this as "a host of studies [that have] concluded that racial classification schemes can account for only a negligible proportion of human genetic diversity," including the studies listed in the table below.| Author(s) | Year | Title | Characteristic Studied | Proportion of Variation Within Groups

(rather than among populations)

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lewontin | 1972 | The apportionment of human

diversity

|

17 blood groups | 85.4% |

| Barbujani et al. | 1997 | An apportionment of human DNA diversity | 79 RFLP, 30 microsatellite loci | 84.5% |

| Seielstad, Minch and

Cavalli-Sforza

|

1998 | Genetic evidence for a higher female migration rate in humans | 29 autosomal microsatellite loci | 97.8% |

| 10 Y chromosome

microsatellite loci

|

83.5% |

These average numbers, however, do not mean that every population harbors an equal amount of diversity. In fact, some human populations contain far more genetic diversity than others, which is consistent with the likely African origin of modern humans. Therefore, populations outside of Africa may have undergone serial founder effects that limited their genetic diversity.

The FST statistic has come under criticism by A. W. F. Edwards and Jeffrey Long and Rick Kittles. British statistician and evolutionary biologist A. W. F. Edwards faulted Lewontin's methodology for basing his conclusions on simple comparison of genes and rather on a more complex structure of gene frequencies. Long and Kittles' objection is also methodological: according to them the FST is based on a faulty underlying assumptions that all populations contain equally genetic diverse members and that continental groups diverged at the same time. Sarich and Miele have also argued that estimates of genetic difference between individuals of different populations understate differences between groups because they fail to take into account human diploidy.

Keith Hunley, Graciela Cabana, and Jeffrey Long created a revised statistical model to account for unequally divergent population lineages and local populations with differing degrees of diversity. Their 2015 paper applies this model to the Human Genome Diversity Project sample of 1,037 individuals in 52 populations. They found that least diverse population examined, the Surui, "harbors nearly 60% of the total species’ diversity." Long and Kittles had noted earlier that the Sokoto people of Africa contains virtually all of human genetic diversity. Their analysis also found that non-African populations are a taxonomic subgroup of African populations, that "some African populations are equally related to other African populations and to non-African populations," and that "outside of Africa, regional groupings of populations are nested inside one another, and many of them are not monophyletic."

Similarity of group members

Multiple studies since 1972 have backed up the claim that, "The average proportion of genetic differences between individuals from different human populations only slightly exceeds that between unrelated individuals from a single population."| Africans | Europeans | Asians | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europeans | 36.5 | — | — |

| Asians | 35.5 | 38.3 | — |

| Indigenous Americans | 26.1 | 33.4 | 35 |

Edwards (2003) claims, "It is not true, as Nature claimed, that 'two random individuals from any one group are almost as different as any two random individuals from the entire world'" and Risch et al. (2002) state "Two Caucasians are more similar to each other genetically than a Caucasian and an Asian." However Bamshad et al. (2004) used the data from Rosenberg et al. (2002) to investigate the extent of genetic differences between individuals within continental groups relative to genetic differences between individuals between continental groups. They found that though these individuals could be classified very accurately to continental clusters, there was a significant degree of genetic overlap on the individual level, to the extent that, using 377 loci, individual Europeans were about 38% of the time more genetically similar to East Asians than to other Europeans.

Witherspoon et al. (2007) have argued that even when individuals can be reliably assigned to specific population groups, it may still be possible for two randomly chosen individuals from different populations/clusters to be more similar to each other than to a randomly chosen member of their own cluster, when sampling a small number of SNPs (as in the case with scientists James Watson, Craig Venter and Seong-Jin Kim). They state that using around one-thousand SNPs, individuals from different populations/clusters are never more similar, which they state some may find surprising. Witherspoon et al. conclude that "caution should be used when using geographic or genetic ancestry to make inferences about individual phenotypes".

Blood polymorphism study

A 1994 study by Cavalli-Sforza and colleagues evaluated genetic distances among 42 native populations based on 120 blood polymorphisms. The populations were grouped into nine clusters: African (sub-Saharan), Caucasoid (European), Caucasoid (extra-European), northern Mongoloid (excluding Arctic populations), northeast Asian Arctic, southern Mongoloid (mainland and insular Southeast Asia), Pacific islander, New Guinean and Australian, and American (Amerindian). Although the clusters demonstrate varying degrees of homogeneity, the nine-cluster model represents a majority (80 out of 120) of single-trait trees and is useful in demonstrating the phenetic relationship among these populations.The greatest genetic distance between two continents is between Africa and Oceania, at 0.2470. This measure of genetic distance reflects the isolation of Australia and New Guinea since the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, when Oceania was isolated from mainland Asia due to rising sea levels. The next-largest genetic distance is between Africa and the Americas, at 0.2260. This is expected, since the longest geographic distance by land is between Africa and South America. The shortest genetic distance, 0.0155, is between European and extra-European Caucasoids. Africa is the most genetically divergent continent, with all other groups more related to each other than to sub-Saharan Africans. This is expected, according to the single-origin hypothesis. Europe has a general genetic variation about three times less than that of other continents; the genetic contribution of Asia and Africa to Europe is thought to be two-thirds and one-third, respectively.

Genetic cluster studies

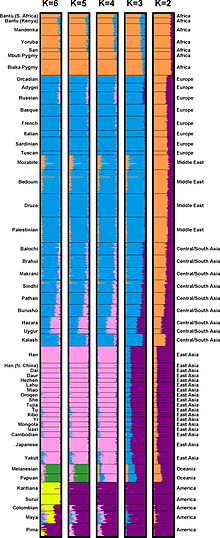

Gene clusters from Rosenberg (2006) for K=7 clusters. (Cluster analysis

divides a dataset into any prespecified number of clusters.)

Individuals have genes from multiple clusters. The cluster prevalent

only among the Kalash people (yellow) only splits off at K=7 and greater.

Genetic structure studies are carried out using statistical computer programs designed to find clusters of genetically similar individuals within a sample of individuals. Studies such as those by Risch and Rosenberg use a computer program called STRUCTURE to find human populations (gene clusters). It is a statistical program that works by placing individuals into one of an arbitrary number of clusters based on their overall genetic similarity, many possible pairs of clusters are tested per individual to generate multiple clusters. The basis for these computations are data describing a large number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), genetic insertions and deletions (indels), microsatellite markers (or short tandem repeats, STRs) as they appear in each sampled individual. Cluster analysis divides a dataset into any prespecified number of clusters.

These clusters are based on multiple genetic markers that are often shared between different human populations even over large geographic ranges. The notion of a genetic cluster is that people within the cluster share on average similar allele frequencies to each other than to those in other clusters. (A. W. F. Edwards, 2003 but see also infobox "Multi Locus Allele Clusters") In a test of idealised populations, the computer programme STRUCTURE was found to consistently underestimate the numbers of populations in the data set when high migration rates between populations and slow mutation rates (such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms) were considered. In 2004, Lynn Jorde and Steven Wooding argued that "Analysis of many loci now yields reasonably accurate estimates of genetic similarity among individuals, rather than populations. Clustering of individuals is correlated with geographic origin or ancestry."

A number of genetic cluster studies have been conducted since 2002, including the following:

| Authors | Year | Title | Sample size / number of populations sampled | Sample | Markers |

| Rosenberg et al. | 2002 | Genetic Structure of Human Populations | 1056 / 52 | Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP-CEPH) | 377 STRs |

| Serre & Pääbo | 2004 | Worldwide Human Relationships Inferred from Genome-Wide Patterns of Variation | 89 / 15 | a: HGDP | 20 STRs |

| 90 / geographically distributed individuals | b: Jorde 1997 | ||||

| Rosenberg et al. | 2005 | Clines, Clusters, and the Effect of Study Design on the Inference of Human Population Structure | 1056 / 52 | Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP-CEPH) | 783 STRs + 210 indels |

| Li et al. | 2008 | Worldwide Human Relationships Inferred from Genome-Wide Patterns of Variation | 938 / 51 | Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP-CEPH) | 650,000 SNPs |

| Tishkoff et al. | 2009 | The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans | ~3400 / 185 | HGDP-CEPH plus 133 additional African populations and Indian individuals | 1327 STRs + indels |

| Xing et al. | 2010 | Toward a more uniform sampling of human genetic diversity: A survey of worldwide populations by high-density genotyping | 850 / 40 | HapMap plus 296 individuals | 250,000 SNPs |

In a 2005 paper, Rosenberg and his team acknowledged that findings of a study on human population structure are highly influenced by the way the study is designed. They reported that the number of loci, the sample size, the geographic dispersion of the samples and assumptions about allele-frequency correlation all have an effect on the outcome of the study.

In a review of studies of human genome diversity, Guido Barbujani and colleagues note that various cluster studies have identified different numbers of clusters with different boundaries. They write that discordant patterns of genetic variation and high within-population genetic diversity "make it difficult, or impossible, to define, once and for good, the main genetic clusters of humankind."

Genetic clustering was also criticized by Penn State anthropologists Kenneth Weiss and Brian Lambert. They asserted that understanding human population structure in terms of discrete genetic clusters misrepresents the path that produced diverse human populations that diverged from shared ancestors in Africa. Ironically, by ignoring the way population history actually works as one process from a common origin rather than as a string of creation events, structure analysis that seems to present variation in Darwinian evolutionary terms is fundamentally non-Darwinian."

Clusters by Rosenberg et al. (2002, 2005)

A major finding of Rosenberg and colleagues (2002) was that when five clusters were generated by the program (specified as K=5), "clusters corresponded largely to major geographic regions." Specifically, the five clusters corresponded to Africa, Europe plus the Middle East plus Central and South Asia, East Asia, Oceania, and the Americas. The study also confirmed prior analyses by showing that, "Within-population differences among individuals account for 93 to 95% of genetic variation; differences among major groups constitute only 3 to 5%."

Human population structure can be inferred from multilocus DNA sequence data (Rosenberg

et al. 2002, 2005). Individuals from 52 populations were examined at

993 DNA markers. This data was used to partition individuals into K = 2,

3, 4, 5, or 6 gene clusters. In this figure, the average fractional

membership of individuals from each population is represented by

horizontal bars partitioned into K colored segments.

Rosenberg and colleagues (2005) have argued, based on cluster analysis, that populations do not always vary continuously and a population's genetic structure is consistent if enough genetic markers (and subjects) are included. "Examination of the relationship between genetic and geographic distance supports a view in which the clusters arise not as an artifact of the sampling scheme, but from small discontinuous jumps in genetic distance for most population pairs on opposite sides of geographic barriers, in comparison with genetic distance for pairs on the same side. Thus, analysis of the 993-locus dataset corroborates our earlier results: if enough markers are used with a sufficiently large worldwide sample, individuals can be partitioned into genetic clusters that match major geographic subdivisions of the globe, with some individuals from intermediate geographic locations having mixed membership in the clusters that correspond to neighboring regions." They also wrote, regarding a model with five clusters corresponding to Africa, Eurasia (Europe, Middle East, and Central/South Asia), East Asia, Oceania, and the Americas: "For population pairs from the same cluster, as geographic distance increases, genetic distance increases in a linear manner, consistent with a clinal population structure. However, for pairs from different clusters, genetic distance is generally larger than that between intracluster pairs that have the same geographic distance. For example, genetic distances for population pairs with one population in Eurasia and the other in East Asia are greater than those for pairs at equivalent geographic distance within Eurasia or within East Asia. Loosely speaking, it is these small discontinuous jumps in genetic distance—across oceans, the Himalayas, and the Sahara—that provide the basis for the ability of STRUCTURE to identify clusters that correspond to geographic regions".

Rosenberg stated that their findings "should not be taken as evidence of our support of any particular concept of biological race (...). Genetic differences among human populations derive mainly from gradations in allele frequencies rather than from distinctive 'diagnostic' genotypes." The study's overall results confirmed that genetic difference within populations is between 93 and 95%. Only 5% of genetic variation is found between groups.

Criticism

The Rosenberg study has been criticised on several grounds.The existence of allelic clines and the observation that the bulk of human variation is continuously distributed, has led some scientists to conclude that any categorization schema attempting to partition that variation meaningfully will necessarily create artificial truncations. (Kittles & Weiss 2003). It is for this reason, Reanne Frank argues, that attempts to allocate individuals into ancestry groupings based on genetic information have yielded varying results that are highly dependent on methodological design. Serre and Pääbo (2004) make a similar claim:

The absence of strong continental clustering in the human gene pool is of practical importance. It has recently been claimed that "the greatest genetic structure that exists in the human population occurs at the racial level" (Risch et al. 2002). Our results show that this is not the case, and we see no reason to assume that "races" represent any units of relevance for understanding human genetic history.In a response to Serre and Pääbo (2004), Rosenberg et al. (2005) maintain that their clustering analysis is robust. Additionally, they agree with Serre and Pääbo that membership of multiple clusters can be interpreted as evidence for clinality (isolation by distance), though they also comment that this may also be due to admixture between neighbouring groups (small island model). Thirdly they comment that evidence of clusterdness is not evidence for any concepts of "biological race".

Clustering does not particularly correspond to continental divisions. Depending on the parameters given to their analytical program, Rosenberg and Pritchard were able to construct between divisions of between 4 and 20 clusters of the genomes studied, although they excluded analysis with more than 6 clusters from their published article. Probability values for various cluster configurations varied widely, with the single most likely configuration coming with 16 clusters although other 16-cluster configurations had low probabilities. Overall, "there is no clear evidence that K=6 was the best estimate" according to geneticist Deborah Bolnick (2008:76-77). The number of genetic clusters used in the study was arbitrarily chosen. Although the original research used different number of clusters, the published study emphasized six genetic clusters. The number of genetic clusters is determined by the user of the computer software conducting the study. Rosenberg later revealed that his team used pre-conceived numbers of genetic clusters from six to twenty "but did not publish those results because Structure [the computer program used] identified multiple ways to divide the sampled individuals". Dorothy Roberts, a law professor, asserts that "there is nothing in the team's findings that suggests that six clusters represent human population structure better than ten, or fifteen, or twenty." When instructed to find two clusters, the program identified two populations anchored around by Africa and by the Americas. In the case of six clusters, the entirety of Kalesh people, an ethnic group living in Northern Pakistan, was added to the previous five.

Commenting on Rosenberg's study, law professor Dorothy Roberts wrote that "the study actually showed that there are many ways to slice the expansive range of human genetic variation.

Clusters in Tishkoff et al. 2009

Sarah A. Tishkoff and colleagues analyzed a global sample consisting of 952 individuals from the HGDP-CEPH survey, 2432 Africans from 113 ethnic groups, 98 African Americans, 21 Yemenites, 432 individuals of Indian descent, and 10 Native Australians. A global STRUCTURE analysis of these individuals examined 1327 polymorphic markers, including of 848 STRs, 476 indels, and 3 SNPs. The authors reported cluster results for K=2 to K=14. Within Africa, six ancestral clusters were inferred through Bayesian analysis, which were closely linked with ethnolinguistic heritage. Bantu populations grouped with other Niger-Congo-speaking populations from West Africa. African Americans largely belonged to this Niger-Congo cluster, but also had significant European ancestry. Nilo-Saharan populations formed their own cluster. Chadic populations clustered with the Nilo-Saharan groups, suggesting that most present-day Chadic speakers originally spoke languages from the Nilo-Saharan family and later adopted Afro-Asiatic languages. Nilotic populations from the African Great Lakes largely belonged to this Nilo-Saharan cluster too, but also had some Afro-Asiatic influence due to assimilation of Cushitic groups over the last 3,000 years. Khoisan populations formed their own cluster, which grouped closest with the Pygmy cluster. The Cape Coloured showed assignments from the Khoisan, European and other clusters due to the population's mixed heritage. The Hadza and Sandawe populations formed their own cluster. An Afro-Asiatic cluster was also discerned, with the Afro-Asiatic speakers from North Africa and the Horn of Africa forming a contiguous group. Afro-Asiatic speakers in the Great Lakes region largely belonged to this Afro-Asiatic cluster as well, but also had some Bantu and Nilotic influence due to assimilation of adjacent groups over the last 3,000 years. The remaining inferred ancestral clusters were associated with European, Middle Eastern, Oceanian, Indian, Native American and East Asian populations.Examining effects of sampling in Xing et al. 2010

Jinchuan Xing and colleagues used an alternate dataset of human genotypes including HapMap samples and their own samples (296 new individuals from 13 populations), for a total of 40 populations distributed roughly evenly across the Earth's land surface. They found that the alternate sampling reduced the FST estimate of inter-population differences from 0.18 to 0.11, suggesting that the higher number may be an artifact of uneven sampling. They conducted a cluster analysis using the ADMIXTURE program and found that "genetic diversity is distributed in a more clinal pattern when more geographically intermediate populations are sampled."HUGO Asian study

A study by the HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium in 2009 using the similar principal components analysis found that East Asian and South-East Asian populations clustered together, and suggested a common origin for these populations. At the same time they observed a broad discontinuity between this cluster and South Asia, commenting "most of the Indian populations showed evidence of shared ancestry with European populations". It was noted that "genetic ancestry is strongly correlated with linguistic affiliations as well as geography".Controversy of genetic clustering and associations with "race"

Studies of clustering reopened a debate on the scientific reality of race, or lack thereof. In the late 1990s Harvard evolutionary geneticist Richard Lewontin stated that "no justification can be offered for continuing the biological concept of race. (...) Genetic data shows that no matter how racial groups are defined, two people from the same racial group are about as different from each other as two people from any two different racial groups. This view has been affirmed by numerous authors and the American Association of Physical Anthropologists since. A.W.F. Edwards as well as Rick Kittles and Jeffrey Long have criticized Lewontin's methodology, with Long noting that there are more similarities between humans and chimpanzees than differences, and more genetic variation within chimps and humans than between them. Edwards also charged that Lewontin made an "unjustified assault on human classification, which he deplored for social reasons". In their 2015 article, Keith Hunley, Graciela Cabana, and Jeffrey Long recalculate the apportionment of human diversity using a more complex model than Lewontin and his successors. They conclude: "In sum, we concur with Lewontin’s conclusion that Western-based racial classifications have no taxonomic significance, and we hope that this research, which takes into account our current understanding of the structure of human diversity, places his seminal finding on firmer evolutionary footing."Genetic clustering studies, and particularly the five-cluster result published by Rosenberg's team in 2002, have been interpreted by journalist Nicholas Wade, evolutionary biologist Armand Marie Leroi, and others as demonstrating the biological reality of race. For Leroi, "Race is merely a shorthand that enables us to speak sensibly, though with no great precision, about genetic rather than cultural or political differences." He states that, "One could sort the world's population into 10, 100, perhaps 1,000 groups", and describes Europeans, Basques, Andaman Islanders, Ibos, and Castillians each as a "race". In response to Leroi's claims, the Social Science Research Council convened a panel of experts to discuss race and genomics online. In their 2002 and 2005 papers, Rosenberg and colleagues disagree that their data implies the biological reality of race.

In 2006, Lewontin wrote that any genetic study requires some priori concept of race or ethnicity in order to package human genetic diversity into a defined, limited number of biological groupings. Informed by genetics, zoologists have long discarded the concept of race for dividing groups of non-human animal populations within a species. Defined on varying criteria, in the same species a widely varying number of races could be distinguished. Lewontin notes that genetic testing revealed that "because so many of these races turned out to be based on only one or two genes, two animals born in the same litter could belong to different 'races'".

Studies that seek to find genetic clusters are only as informative as the populations they sample. For example, Risch and Burchard relied on two or three local populations from five continents, which together were supposed to represent the entire human race. Another genetic clustering study used three sub-Saharan population groups to represent Africa; Chinese, Japanese, and Cambodian samples for East Asia; Northern European and Northern Italian samples to represent "Caucasians". Entire regions, subcontinents, and landmasses are left out of many studies. Furthermore, social geographical categories such "East Asia" and "Caucasians" were not defined. "A handful of ethnic groups to symbolize an entire continent mimic a basic tenet of racial thinking: that because races are composed of uniform individuals, anyone can represent the whole group" notes Roberts.

The model of Big Few fails when including overlooked geographical regions such as India. The 2003 study which examined fifty-eight genetic markers found that Indian populations owe their ancestral lineages to Africa, Central Asia, Europe, and southern China. Reardon, from Princeton University, asserts that flawed sampling methods are built into many genetic research projects. The Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) relied on samples which were assumed to be geographically separate and isolated. The relatively small sample sizes of indigenous populations for the HGDP do not represent the human species' genetic diversity, nor do they portray migrations and mixing population groups which has been happening since prehistoric times. Geographic areas such as the Balkans, the Middle East, North and East Africa, and Spain are seldom included in genetic studies. East and North African indigenous populations, for example, are never selected to represent Africa because they do not fit the profile of "black" Africa. The sampled indigenous populations of the HGDP are assumed to be "pure"; the law professor Roberts claims that "their unusual purity is all the more reason they cannot stand in for all the other populations of the world that marked by intermixture from migration, commerce, and conquest."

King and Motulsky, in a 2002 Science article, state that "While the computer-generated findings from all of these studies offer greater insight into the genetic unity and diversity of the human species, as well as its ancient migratory history, none support dividing the species into discrete, genetically determined racial categories". Cavalli-Sforza asserts that classifying clusters as races would be a "futile exercise" because "every level of clustering would determine a different population and there is no biological reason to prefer a particular one". Bamshad, in 2004 paper published in Nature, asserts that a more accurate study of human genetic variation would use an objective sampling method, which would choose populations randomly and systematically across the world, including those populations which are characterized by historical intermingling, instead of cherry-picking population samples which fit a priori concepts of racial classification. Roberts states that "if research collected DNA samples continuously from region to region throughout the world, they would find it impossible to infer neat boundaries between large geographical groups."

Anthropologists such as C. Loring Brace, philosophers Jonathan Kaplan and Rasmus Winther, and geneticist Joseph Graves, have argued that while it is certainly possible to find biological and genetic variation that corresponds roughly to the groupings normally defined as "continental races", this is true for almost all geographically distinct populations. The cluster structure of the genetic data is therefore dependent on the initial hypotheses of the researcher and the populations sampled. When one samples continental groups the clusters become continental; if one had chosen other sampling patterns the clustering would be different. Weiss and Fullerton have noted that if one sampled only Icelanders, Mayans and Maoris, three distinct clusters would form and all other populations could be described as being clinally composed of admixtures of Maori, Icelandic and Mayan genetic materials. Kaplan and Winther therefore argue that seen in this way both Lewontin and Edwards are right in their arguments. They conclude that while racial groups are characterized by different allele frequencies, this does not mean that racial classification is a natural taxonomy of the human species, because multiple other genetic patterns can be found in human populations that cross-cut racial distinctions. Moreover, the genomic data under-determines whether one wishes to see subdivisions (i.e., splitters) or a continuum (i.e., lumpers). Under Kaplan and Winther's view, racial groupings are objective social constructions (see Mills 1998 ) that have conventional biological reality only insofar as the categories are chosen and constructed for pragmatic scientific reasons.

Commercial ancestry testing and individual ancestry

Commercial ancestry testing companies, who use genetic clustering data, have been also heavily criticized. Limitations of genetic clustering are intensified when inferred population structure is applied to individual ancestry. The type of statistical analysis conducted by scientists translates poorly into individual ancestry because they are looking at difference in frequencies, not absolute differences between groups. Commercial genetic genealogy companies are guilty of what Pillar Ossorio calls the "tendency to transform statistical claims into categorical ones". Not just individuals of the same local ethnic group, but two siblings may end up beings as members of different continental groups or "races" depending on the alleles they inherit.Many commercial companies use data from the International HapMap Project (HapMap)'s initial phrase, where population samples were collected from four ethnic groups in the world: Han Chinese, Japanese, Yoruba Nigerian, and Utah residents of Northern European ancestry. If a person has ancestry from a region where the computer program does not have samples, it will compensate with the closest sample that may have nothing to do with the customer's actual ancestry: "Consider a genetic ancestry testing performed on an individual we will call Joe, whose eight great-grandparents were from southern Europe. The HapMap populations are used as references for testing Joe's genetic ancestry. The HapMap's European samples consist of "northern" Europeans. In regions of Joe's genome that vary between northern and southern Europe (such regions might include the lactase gene), the genetic ancestry test is using the HapMap reference population is likely to incorrectly assign the ancestry of that portion of the genome to a non-European population because that genomic region will appear to be more similar to the HapMap's Yoruba or Han Chinese samples than to Northern European samples. Likewise, a person having Western European and Western African ancestries may have ancestors from Western Europe and West Africa, or instead be assigned to East Africa where various ancestries can be found. "Telling customers that they are a composite of several anthropological groupings reinforces three central myths about race: that there are pure races, that each race contains people who are fundamentally the same and fundamentally different from people in other races, and that races can be biologically demarcated." Many companies base their findings on inadequate and unscientific sampling methods. Researchers have never sampled the world's populations in a systematic and random fashion.