Green anarchism (or eco-anarchism) is a school of thought within anarchism which puts a particular emphasis on environmental issues. A green anarchist theory is normally one that extends anarchist ideology beyond a critique of human interactions, and includes a critique of the interactions between humans and non-humans as well. This often culminates in an anarchist revolutionary praxis that is not merely dedicated to human liberation, but also to some form of nonhuman liberation, and that aims to bring about an environmentally sustainable anarchist society.

Important early influences were Henry David Thoreau, Leo Tolstoy and Élisée Reclus. In the late 19th century there emerged anarcho-naturism as the fusion of anarchism and naturist philosophies within individualist anarchist circles in France, Spain, Cuba, and Portugal. Important contemporary currents (some of which may be mutually exclusive) include anarcho-primitivism, which offers a critique of technology and argues that anarchism is best suited to uncivilised ways of life, Green syndicalism, a Green anarcho-socialist political stance made up of anarcho-syndicalist views, and veganarchism: which argues that human liberation and animal liberation are inseparable; and social ecology, which argues that the hierarchical domination of nature by human stems from the hierarchical domination of human by human.

Early ecoanarchism

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau, influential early green anarchist who wrote Walden

Anarchism started to have an ecological view mainly in the writings of American anarchist and transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau. In his book Walden he advocates simple living and self-sufficiency among natural surroundings in resistance to the advancement of industrial civilization. The work is part personal declaration of independence, social experiment, voyage of spiritual discovery, satire, and manual for self-reliance. First published in 1854, it details Thoreau's experiences over the course of two years, two months, and two days in a cabin he built near Walden Pond, amidst woodland owned by his friend and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson, near Concord, Massachusetts. The book compresses the time into a single calendar year and uses passages of four seasons to symbolize human development. By immersing himself in nature, Thoreau hoped to gain a more objective understanding of society through personal introspection. Simple living and self-sufficiency were Thoreau's other goals, and the whole project was inspired by transcendentalist philosophy, a central theme of the American Romantic Period. As Thoreau made clear in his book, his cabin was not in wilderness but at the edge of town, about two miles (3.2 km) from his family home.

As such "Many have seen in Thoreau one of the precursors of ecologism and anarcho-primitivism represented today in John Zerzan. For George Woodcock this attitude can be also motivated by certain idea of resistance to progress and of rejection of the growing materialism which is the nature of American society in the mid 19th century."[9] John Zerzan himself included the text "Excursions" (1863) by Thoreau in his edited compilation of writings called Against civilization: Readings and reflections from 1999.

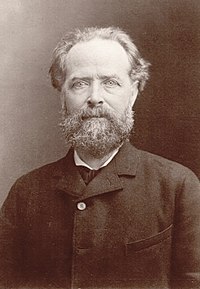

Élisée Reclus

Élisée Reclus, French anarchist geographer and environmentalist

Élisée Reclus (15 March 1830 – 4 July 1905), also known as Jacques Élisée Reclus, was a renowned French geographer, writer and anarchist. He produced his 19-volume masterwork La Nouvelle Géographie universelle, la terre et les hommes ("Universal Geography"), over a period of nearly 20 years (1875–1894). In 1892, he was awarded the prestigious Gold Medal of the Paris Geographical Society for this work, despite his having been banished from France because of his political activism. According to Kirkpatrick Sale:

His geographical work, thoroughly researched and unflinchingly scientific, laid out a picture of human-nature interaction that we today would call bioregionalism. It showed, with more detail than anyone but a dedicated geographer could possibly absorb, how the ecology of a place determined the kinds of lives and livelihoods its denizens would have and thus how people could properly live in self-regarding and self-determined bioregions without the interference of large and centralized governments that always try to homogenize diverse geographical areas.For the authors of An Anarchist FAQ Reclus "argued that a "secret harmony exists between the earth and the people whom it nourishes, and when imprudent societies let themselves violate this harmony, they always end up regretting it." Similarly, no contemporary ecologist would disagree with his comments that the "truly civilised man [and women] understands that his [or her] nature is bound up with the interest of all and with that of nature. He [or she] repairs the damage caused by his predecessors and works to improve his domain."

Reclus advocated nature conservation and opposed meat-eating and cruelty to animals. He was a vegetarian. As a result, his ideas are seen by some historians as anticipating the modern social ecology and animal rights movements. Shortly before his death, Reclus completed L'Homme et la terre (1905). In it, he added to his previous greater works by considering humanity's development relative to its geographical environment. Reclus was also an early proponent of naturism.

Anarcho-naturism

In the late 19th century Anarchist naturism appeared as the union of anarchist and naturist philosophies. Mainly it had importance within individualist anarchist circles in Spain, France, Portugal, and Cuba.Anarcho-naturism advocated vegetarianism, free love, nudism and an ecological world view within anarchist groups and outside them. Anarcho-naturism promoted an ecological worldview, small ecovillages, and most prominently nudism as a way to avoid the artificiality of the industrial mass society of modernity. Naturist individualist anarchists saw the individual in his biological, physical and psychological aspects and tried to eliminate social determinations. Important promoters of this were Henri Zisly and Emile Gravelle who collaborated in La Nouvelle Humanité followed by Le Naturien, Le Sauvage, L'Ordre Naturel, & La Vie Naturelle

France

Richard D. Sonn comments on the influence of naturist views in the wider French anarchist movement:In her memoir of her anarchist years that was serialized in Le Matin in 1913, Rirette Maîtrejean made much of the strange food regimens of some of the compagnons. ... She described the "tragic bandits" of the Bonnot gang as refusing to eat meat or drink wine, preferring plain water. Her humorous comments reflected the practices of the "naturist" wing of individualist anarchists who favored a simpler, more "natural" lifestyle centered on a vegetarian diet. In the 1920s, this wing was expressed by the journal Le Néo-Naturien, Revue des Idées Philosophiques et Naturiennes. Contributors condemned the fashion of smoking cigarettes, especially by young women; a long article of 1927 actually connected cigarette smoking with cancer! Others distinguished between vegetarians, who foreswore the eating of meat, from the stricter "vegetalians," who ate nothing but vegetables. An anarchist named G. Butaud, who made this distinction, opened a restaurant called the Foyer Végétalien in the nineteenth arrondissement in 1923. Other issues of the journal included vegetarian recipes. In 1925, when the young anarchist and future detective novelist Léo Malet arrived in Paris from Montpellier, he initially lodged with anarchists who operated another vegetarian restaurant that served only vegetables, with neither fish nor eggs. Nutritional concerns coincided with other means of encouraging health bodies, such as nudism and gymnastics. For a while in the 1920s, after they were released from jail for antiwar and birth-control activities, Jeanne and Eugène Humbert retreated to the relative safety of the "integral living" movement that promoted nude sunbathing and physical fitness, which were seen as integral aspects of health in the Greek sense of gymnos, meaning nude. This back-to-nature, primitivist current was not a monopoly of the left; the same interests were echoed by right-wing Germans in the interwar era. In France, however, these proclivities were mostly associated with anarchists, insofar as they suggested an ideal of self-control and the rejection of social taboos and prejudices.

Henri Zisly

Henri Zisly (born in Paris, November 2, 1872; died in 1945) was a French individualist anarchist and naturist. He participated alongside Henri Beylie and Émile Gravelle in many journals such as La Nouvelle Humanité and La Vie Naturelle, which promoted anarchist-naturism. In 1902, he was one of the main initiators, alongside Georges Butaud and Sophie Zaïkowska, of the cooperative Colonie de Vaux established in Essômes-sur-Marne, in Aisne.Zisly's political activity, "primarily aimed at supporting a return to 'natural life' through writing and practical involvement, stimulated lively confrontations within and outside the anarchist environment. Zisly vividly criticized progress and civilization, which he regarded as 'absurd, ignoble, and filthy.' He openly opposed industrialization, arguing that machines were inherently authoritarian, defended nudism, advocated a non-dogmatic and non-religious adherence to the 'laws of nature,' recommended a lifestyle based on limited needs and self-sufficiency, and disagreed with vegetarianism, which he considered 'anti-scientific.'"

Cuba

The historian Kirwin R. Schaffer in his study of Cuban anarchism reports anarcho-naturism as "A third strand within the island's anarchist movement" alongside anarcho-communism and anarcho-syndicalism. Naturism was a global alternative health and lifestyle movement. Naturists focused on redefining one's life to live simply, eat cheap but nutritious vegetarian diets, and raise one's own food if possible. The countryside was posited as a romantic alternative to urban living, and some naturists even promoted what they saw as the healthful benefits of nudism. Globally, the naturist movement counted anarchists, liberals, and socialists as its followers. However, in Cuba a particular "anarchist" dimension evolved led by people like Adrián del Valle, who spearheaded the Cuban effort to shift naturism's focus away from only individual health to naturism having a "social emancipatory" function."Schaffer reports the influence that anarcho-naturism had outside naturists circles. So "For instance, nothing inherently prevented an anarcho-syndicalist in the Havana restaurant workers' union from supporting the alternative health care programs of the anarcho-naturists and seeing those alternative practices as 'revolutionary.'". "Anarcho-naturists promoted a rural ideal, simple living, and being in harmony with Nature as ways to save the laborers from the increasingly industrialized character of Cuba. Besides promoting an early twentieth-century "back-to-the-land" movement, they used these romantic images of Nature to illustrate how far removed a capitalist industrialized Cuba had departed from an anarchist view of natural harmony." The main propagandizer in Cuba of anarcho-naturism was the Catalonia born "Adrián del Valle (aka Palmiro de Lidia) ... Over the following decades, Del Valle became a constant presence in not only the anarchist press that proliferated in Cuba but also mainstream literary publications ... From 1912 to 1913 he edited the freethinking journal El Audaz. Then he began his largest publishing job by helping to found and edit the monthly alternative health magazine that followed the anarcho-naturist line Pro-Vida.

Spain

Anarcho-naturism was quite important at the end of the 1920s in the spanish anarchist movement. In France, later important propagandists of anarcho-naturism include Henri Zisly and Émile Gravelle whose ideas were important in individualist anarchist circles in Spain, where Federico Urales (pseudonym of Joan Montseny) promoted the ideas of Gravelle and Zisly in La Revista Blanca (1898–1905):

The linking role played by the Sol y Vida group was very important. The goal of this group was to take trips and enjoy the open air. The Naturist athenaeum, Ecléctico, in Barcelona, was the base from which the activities of the group were launched. First Etica and then Iniciales, which began in 1929, were the publications of the group, which lasted until the Spanish Civil War. We must be aware that the naturist ideas expressed in them matched the desires that the libertarian youth had of breaking up with the conventions of the bourgeoisie of the time. That is what a young worker explained in a letter to Iniciales. He writes it under the odd pseudonym of silvestre del campo (wild man in the country). "I find great pleasure in being naked in the woods, bathed in light and air, two natural elements we cannot do without. By shunning the humble garment of an exploited person, (garments which, in my opinion, are the result of all the laws devised to make our lives bitter), we feel there no others left but just the natural laws. Clothes mean slavery for some and tyranny for others. Only the naked man who rebels against all norms, stands for anarchism, devoid of the prejudices of outfit imposed by our money-oriented society.The "relation between Anarchism and Naturism gives way to the Naturist Federation, in July 1928, and to the lV Spanish Naturist Congress, in September 1929, both supported by the Libertarian Movement. However, in the short term, the Naturist and Libertarian movements grew apart in their conceptions of everyday life. The Naturist movement felt closer to the Libertarian individualism of some French theoreticians such as Henri Ner (real name of Han Ryner) than to the revolutionary goals proposed by some Anarchist organisations such as the FAI, (Federación Anarquista Ibérica)". This ecological tendency in Spanish anarchism was strong enough as to call the attention of the CNT–FAI in Spain. Daniel Guérin in Anarchism: From Theory to Practice reports:

Spanish anarcho-syndicalism had long been concerned to safeguard the autonomy of what it called "affinity groups." There were many adepts of naturism and vegetarianism among its members, especially among the poor peasants of the south. Both these ways of living were considered suitable for the transformation of the human being in preparation for a libertarian society. At the Saragossa congress the members did not forget to consider the fate of groups of naturists and nudists, "unsuited to industrialization." As these groups would be unable to supply all their own needs, the congress anticipated that their delegates to the meetings of the confederation of communes would be able to negotiate special economic agreements with the other agricultural and industrial communes. On the eve of a vast, bloody, social transformation, the CNT did not think it foolish to try to meet the infinitely varied aspirations of individual human beings.

Isaac Puente

Isaac Puente was an influential Spanish anarchist during the 1920s and 1930s and an important propagandist of anarcho-naturism, was a militant of both the CNT anarcho-syndicalist trade union and Iberian Anarchist Federation. He published the book El Comunismo Libertario y otras proclamas insurreccionales y naturistas (en:Libertarian Communism and other insurrectionary and naturist proclamations) in 1933, which sold around 100,000 copies, and wrote the final document for the Extraordinary Confederal Congress of Zaragoza of 1936 which established the main political line for the CNT for that year. Puente was a doctor who approached his medical practice from a naturist point of view. He saw naturism as an integral solution for the working classes, alongside Neo-Malthusianism, and believed it concerned the living being while anarchism addressed the social being. He believed capitalist societies endangered the well-being of humans from both a socioeconomic and sanitary viewpoint, and promoted anarcho-communism alongside naturism as a solution.Other countries

Naturism also met anarchism in the United Kingdom. "In many of the alternative communities established in Britain in the early 1900s nudism, anarchism, vegetarianism and free love were accepted as part of a politically radical way of life. In the 1920s the inhabitants of the anarchist community at Whiteway, near Stroud in Gloucestershire, shocked the conservative residents of the area with their shameless nudity." In Italy, during the IX Congress of the Italian Anarchist Federation in Carrara in 1965, a group decided to split off from this organization and created the Gruppi di Iniziativa Anarchica. In the seventies, it was mostly composed of "veteran individualist anarchists with an orientation of pacifism, naturism, etc, ...". American anarcho-syndicalist Sam Dolgoff shows some of the criticism that some people on the other anarchist currents at the time had for anarcho-naturist tendencies. "Speaking of life at the Stelton Colony of New York in the 1930s, noted with disdain that it, "like other colonies, was infested by vegetarians, naturists, nudists, and other cultists, who sidetracked true anarchist goals." One resident "always went barefoot, ate raw food, mostly nuts and raisins, and refused to use a tractor, being opposed to machinery, and he didn't want to abuse horses, so he dug the earth himself." Such self-proclaimed anarchists were in reality "ox-cart anarchists," Dolgoff said, "who opposed organization and wanted to return to a simpler life." In an interview with Paul Avrich before his death, Dolgoff also grumbled, "I am sick and tired of these half-assed artists and poets who object to organization and want only to play with their belly buttons.".Leo Tolstoy and Tolstoyanism

Leo Tolstoy dressed in peasant clothing by Ilya Repin (1901)

Russian Christian anarchist and anarcho-pacifist Leo Tolstoy is also recognized as an early influence in green anarchism. The novelist was struck by the description of Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu ascetic renunciation as being the path to holiness. After reading passages such as the following, which abound in Schopenhauer's ethical chapters, the Russian nobleman chose poverty and formal denial of the will:

But this very necessity of involuntary suffering (by poor people) for eternal salvation is also expressed by that utterance of the Savior (Matthew 19:24): "It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God." Therefore those who were greatly in earnest about their eternal salvation, chose voluntary poverty when fate had denied this to them and they had been born in wealth. Thus Buddha Sakyamuni was born a prince, but voluntarily took to the mendicant's staff; and Francis of Assisi, the founder of the mendicant orders who, as a youngster at a ball, where the daughters of all the notabilities were sitting together, was asked: "Now Francis, will you not soon make your choice from these beauties?" and who replied: "I have made a far more beautiful choice!" "Whom?" "La povertà (poverty)": whereupon he abandoned every thing shortly afterwards and wandered through the land as a mendicant.Despite his misgivings about anarchist violence, Tolstoy took risks to circulate the prohibited publications of anarchist thinkers in Russia, and corrected the proofs of Kropotkin's "Words of a Rebel", illegally published in St Petersburg in 1906. Tolstoy was enthused by the economic thinking of Henry George, incorporating it approvingly into later works such as Resurrection, the book that played a major factor in his excommunication. Tolstoyans identify themselves as Christians, but do not generally belong to an institutional Church. They attempt to live an ascetic and simple life, preferring to be vegetarian, non-smoking, teetotal and chaste. Tolstoyans are considered Christian pacifists and advocate nonresistance in all circumstances. They do not support or participate in the government which they consider immoral, violent and corrupt. Tolstoy rejected the state (as it only exists on the basis of physical force) and all institutions that are derived from it - the police, law courts and army. Tolstoy influenced Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi who set up a cooperative colony called Tolstoy Farm near Johannesburg, South Africa, having been inspired by Tolstoy's ideas. The colony comprising 1,100 acres (450 ha) was funded by the Gandhian Herman Kallenbach and placed at the disposal of the satyagrahis from 1910. He also inspired similar communal experiments in the United States where the residents were also influenced by the views of Henry George and Edward Bellamy, as well as in Russia, England, and the Netherlands.

Mid-20th century

Several anarchists from the mid-20th century like Herbert Read, Ethel Mannin, Leopold Kohr and Paul Goodman held proto-environmental views linked to their anarchism. Mannin's 1944 book Bread and Roses: A Utopian Survey and Blue-Print has been described by anarchist historian Robert Graham as setting forth "an ecological vision in opposition to the prevailing and destructive industrial organization of society".Leopold Kohr

Leopold Kohr (5 October 1909 in Oberndorf bei Salzburg, Austria – 26 February 1994 in Gloucester, England) was an economist, philosopher and political scientist known both for his opposition to the "cult of bigness" in social organization and as one of those who initiated the small is beautiful movement. For almost twenty years he was Professor of Economics and Public Administration at the University of Puerto Rico. He described himself as a "philosophical anarchist." In 1937, Kohr became a freelance correspondent during the Spanish Civil War, where he was impressed by the limited, self-contained governments of the separatist states of Catalonia and Aragon, as well as the small Spanish anarchist city states of Alcoy and Caspe. In his first published essay "Disunion Now: A Plea for a Society based upon Small Autonomous Units", published in Commonweal in 1941, Kohr wrote about a Europe at war: "We have ridiculed the many little states, now we are terrorized by their few successors." He called for the breakup of Europe into hundreds of city states. Kohr developed his ideas in a series of books, including The Breakdown of Nations (1957), Development without Aid (1973) and The Overdeveloped Nations (1977). From Leopold Kohr's most popular work The Breakdown of Nations:... there seems to be only one cause behind all forms of social misery: bigness. Oversimplified as this may seem, we shall find the idea more easily acceptable if we consider that bigness, or oversize, is really much more than just a social problem. It appears to be the one and only problem permeating all creation. Whenever something is wrong, something is too big. ... And if the body of a people becomes diseased with the fever of aggression, brutality, collectivism, or massive idiocy, it is not because it has fallen victim to bad leadership or mental derangement. It is because human beings, so charming as individuals or in small aggregations, have been welded into overconcentrated social units.Later in his academic and writing career he protested the "cult of bigness" and economic growth and promoted the concept of human scale and small community life. He argued that massive external aid to poorer nations stifled local initiatives and participation. His vision called for a dissolution of centralized political and economic structures in favor of local control. Kohr was an important inspiration to the Green, bioregional, Fourth World, decentralist, and anarchist movements, Kohr contributed often to John Papworth's `Journal for the Fourth World', Resurgence. One of Kohr's students was economist E. F. Schumacher, another prominent influence on these movements, whose best selling book Small Is Beautiful took its title from one of Kohr's core principles. Similarly, his ideas inspired Kirkpatrick Sale's books Human Scale (1980) and Dwellers in the Land: The Bioregional Vision (1985). Sale arranged the first American publication of The Breakdown of Nations in 1978 and wrote the foreword.

Murray Bookchin

Murray Bookchin (January 14, 1921 – July 30, 2006) was an American libertarian socialist author, orator, and philosopher. In 1958, Murray Bookchin defined himself as an anarchist, seeing parallels between anarchism and ecology. His first book, Our Synthetic Environment, was published under the pseudonym Lewis Herber in 1962, a few months before Rachel Carson's Silent Spring. The book described a broad range of environmental ills but received little attention because of its political radicalism. His groundbreaking essay "Ecology and Revolutionary Thought" introduced ecology as a concept in radical politics. In 1968 he founded another group that published the influential Anarchos magazine, which published that and other innovative essays on post-scarcity and on ecological technologies such as solar and wind energy, and on decentralization and miniaturization. Lecturing throughout the United States, he helped popularize the concept of ecology to the counterculture.Post-Scarcity Anarchism is a collection of essays written by Murray Bookchin and first published in 1971 by Ramparts Press. It outlines the possible form anarchism might take under conditions of post-scarcity. It is one of Bookchin's major works, and its radical thesis provoked controversy for being utopian and messianic in its faith in the liberatory potential of technology. Bookchin argues that post-industrial societies are also post-scarcity societies, and can thus imagine "the fulfillment of the social and cultural potentialities latent in a technology of abundance". The self-administration of society is now made possible by technological advancement and, when technology is used in an ecologically sensitive manner, the revolutionary potential of society will be much changed. In 1982, his book The Ecology of Freedom had a profound impact on the emerging ecology movement, both in the United States and abroad. He was a principal figure in the Burlington Greens in 1986-90, an ecology group that ran candidates for city council on a program to create neighborhood democracy. In From Urbanization to Cities (originally published in 1987 as The Rise of Urbanization and the Decline of Citizenship), Bookchin traced the democratic traditions that influenced his political philosophy and defined the implementation of the libertarian municipalism concept. A few years later The Politics of Social Ecology, written by his partner of 20 years, Janet Biehl, briefly summarized these ideas.

Jacques Ellul

Jacques Ellul (January 6, 1912 – May 19, 1994) was a French philosopher, law professor, sociologist, lay theologian, and Christian anarchist. He wrote several books about Christianity, the technological society, propaganda, and the interaction between religion and politics. Professor of History and the Sociology of Institutions on the Faculty of Law and Economic Sciences at the University of Bordeaux, he authored 58 books and more than a thousand articles over his lifetime in all, the dominant theme of which has been the threat to human freedom and religion created by modern technique. The Ellulian concept of technique is briefly defined within the "Notes to Reader" section of The Technological Society (1964). What many consider to be Ellul's most important work, The Technological Society (1964) was originally titled: La Technique: L'enjeu du siècle (literally, "The Stake of the Century"). In it, Ellul set forth seven characteristics of modern technology that make efficiency a necessity: rationality, artificiality, automatism of technical choice, self-augmentation, monism, universalism, and autonomy.For Ellul the rationality of technique enforces logical and mechanical organization through division of labor, the setting of production standards, etc. And it creates an artificial system which "eliminates or subordinates the natural world." Today, he argues, the technological society is generally held sacred (cf. Saint Steve Jobs). Since he defines technique as "the totality of methods rationally arrived at, and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity", it is clear that his sociological analysis focuses not on the society of machines as such, but on the society of "efficient techniques".

Contemporary developments

Notable contemporary writers espousing green anarchism include Layla AbdelRahim, Derrick Jensen, Jaime Semprun, George Draffan, John Zerzan, Starhawk and Alan Carter.Social ecology and Communalism

Social ecology is closely related to the work and ideas of Murray Bookchin and influenced by anarchist Peter Kropotkin. Social ecologists assert that the present ecological crisis has its roots in human social problems, and that the domination of human-over-nature stems from the domination of human-over-human.

Bookchin later developed a political philosophy to complement social ecology which he called "Communalism" (spelled with a capital "C" to differentiate it from other forms of communalism). While originally conceived as a form of Social anarchism, he later developed Communalism into a separate ideology which incorporates what he saw as the most beneficial elements of Anarchism, Marxism, syndicalism, and radical ecology.

Politically, Communalists advocate a network of directly democratic citizens' assemblies in individual communities/cities organized in a confederal fashion. This method used to achieve this is called Libertarian Municipalism which involves the establishment of face-to-face democratic institutions which are to grow and expand confederally with the goal of eventually replacing the nation-state.

Janet Biehl (born 1953) is a writer associated with social ecology, the body of ideas developed and publicized by Murray Bookchin. In 1986, she attended the Institute for Social Ecology and there, began a collaborative relationship with Bookchin, working intensively with him over the next two decades in the explication of social ecology from their shared home in Burlington, Vermont.

From 1987 to 2000, she and Bookchin co-wrote and co-published the theoretical newsletter Green Perspectives, later renamed Left Green Perspectives. She is the editor and compiler of The Murray Bookchin Reader (1997); the author of The Politics of Social Ecology: Libertarian Municipalism (1998) and Rethinking Ecofeminist Politics (1991); and coauthor (with Peter Staudenmaier) of Ecofascism: Lessons from the German Experience (1995).

Green Anarchist

The magazine Green Anarchist was for a while the principal voice in the UK advocating green anarchism, an explicit fusion of libertarian socialist and ecological thinking. Founded after the 1984 Stop the City protests, the magazine was launched in the summer of that year by an editorial collective consisting of Alan Albon, Richard Hunt and Marcus Christo. Early issues featured a range of broadly anarchist and ecological ideas, bringing together groups and individuals as varied as Class War, veteran anarchist writer Colin Ward, anarcho-punk band Crass, as well as the Peace Convoy, anti-nuclear campaigners, animal rights activists and so on. However, the diversity that many saw as the publication's greatest strength quickly led to irreconcilable arguments between the essentially pacifist approach of Albon and Christo, and the advocacy of violent confrontation with the State favoured by Hunt. During the 1990s Green Anarchist came under the helm of an editorial collective that included Paul Rogers, Steve Booth and others, during which period the publication became increasingly aligned with primitivism, an anti-civilization philosophy advocated by writers such as John Zerzan and Fredy Perlman. Starting in 1995, Hampshire Police began a series of at least 56 raids, code named 'Operation Washington', that eventually resulted in the August to November 1997 Portsmouth trial of Green Anarchist editors Booth, Saxon Wood, Noel Molland and Paul Rogers, as well as Animal Liberation Front (ALF) Press Officer Robin Webb and Animal Liberation Front Supporters Group (ALFSG) newsletter editor Simon Russell. The defendants organised the GANDALF Defence campaign. Three of the editors of Green Anarchist, Noel Molland, Saxon Wood and Booth were jailed for 'conspiracy to incite'. However, all three were shortly afterwards released on appeal.Fredy Perlman

Fredy Perlman (August 20, 1934 – July 26, 1985) was a Czech-born, naturalised American author, publisher and militant. His most popular work, the book Against His-Story, Against Leviathan!, details the rise of state domination with a retelling of history through the Hobbesian metaphor of the Leviathan. The book remains a major source of inspiration for anti-civilization perspectives in contemporary anarchism, most notably on the thought of philosopher John Zerzan.Anarcho-primitivism

Anarcho-primitivism is an anarchist critique of the origins and progress of civilization. According to anarcho-primitivism, the shift from hunter-gatherer to agricultural subsistence gave rise to social stratification, coercion, and alienation. Anarcho-primitivists advocate a return to non-"civilized" ways of life through deindustrialisation, abolition of the division of labour or specialization, and abandonment of large-scale organization technologies. There are other non-anarchist forms of primitivism, and not all primitivists point to the same phenomenon as the source of modern, civilized problems. Anarcho-primitivists are often distinguished by their focus on the praxis of achieving a feral state of being through "rewilding".John Zerzan

John Zerzan, anarcho-primitivism theorist

John Zerzan is an American anarchist and primitivist philosopher and author. His works criticize agricultural civilization as inherently oppressive, and advocate drawing upon the ways of life of hunter gatherers as an inspiration for what a free society should look like. Some subjects of his criticism include domestication, language, symbolic thought (such as mathematics and art) and the concept of time.

His five major books are Elements of Refusal (1988), Future Primitive and Other Essays (1994), Running on Emptiness (2002), Against Civilization: Readings and Reflections (2005) and Twilight of the Machines (2008). Zerzan was one of the editors of Green Anarchy, a controversial journal of anarcho-primitivist and insurrectionary anarchist thought. He is also the host of Anarchy Radio in Eugene on the University of Oregon's radio station KWVA. He has also served as a contributing editor at Anarchy Magazine and has been published in magazines such as AdBusters. He does extensive speaking tours around the world, and is married to an independent consultant to museums and other nonprofit organizations. In 1974, Black and Red Press published Unions Against Revolution by Spanish ultra-left theorist Grandizo Munis that included an essay by Zerzan which previously appeared in the journal Telos. Over the next 20 years, Zerzan became intimately involved with the Fifth Estate, Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed, Demolition Derby and other anarchist periodicals. He began to question civilization in the early 80's, after having sought to confront issues around the neutrality of technology and division of labour, at the time when Fredy Perlman was making similar conclusions.

Green Anarchy

Green Anarchy was a magazine published by a collective located in Eugene, Oregon. The magazine's focus was primitivism, post-left anarchy, radical environmentalism, African American struggles, anarchist resistance, indigenous resistance, earth and animal liberation, anti-capitalism and supporting political prisoners. It had a circulation of 8,000, partly in prisons, the prison subscribers given free copies of each issue as stated in the magazine. Green Anarchy was started in 2000 and in 2009 the Green Anarchy website shut down, leaving a final, brief message about the cessation of the magazine's publication. The subtitle of the magazine is "An Anti-Civilization Journal of Theory and Action". Author John Zerzan was one of the publication's editors.Species Traitor

Species Traitor is a sporadically published journal of insurrectionary anarcho-primitivism. It is printed as a project of Black and Green Network and edited by anarcho-primitivist writer, Kevin Tucker. ST was initially labeled as a project of the Coalition Against Civilization (CAC) and the Black and Green Network (BAG). The CAC was started towards the end of 1999 in the aftermath of the massive street protests in Eugene (Reclaim the Streets) and in Seattle (WTO) of that year. That aftermath gave a new voice and standing for green anarchist and anarcho-primitivist writers and viewpoints within both the anarchist milieu and the culture at large. The first issue came out in winter of 2000-2001 (currently out of print) and contained a mix of reprints and some original articles from Derrick Jensen and John Zerzan among others. Issue two came in the following year in the wake of Sept. 11 and took a major step from the first issue in becoming something of its own rather than another mouthpiece of green anarchist rhetoric. The articles took a more in depth direction opening a more analytical and critical draw between anarchy and anthropology, attacks on Reason and the Progress/linear views of human history and Future that stand at the base of the ideology of civilization.Vegananarchism

Veganarchism or vegan anarchism, is the political philosophy of veganism (more specifically animal liberation and earth liberation) and anarchism, creating a combined praxis that is designed to be a means for social revolution. This encompasses viewing the state as unnecessary and harmful to animals, both human and non-human, whilst practising a vegan lifestyle. It is either perceived as a combined theory, or that both philosophies are essentially the same. It is further described as an anti-speciesist perspective on green anarchism, or an anarchist perspective on animal liberation.Veganarchists typically view oppressive dynamics within society to be interconnected, from statism, racism and sexism to human supremacy and redefine veganism as a radical philosophy that sees the state as harmful to animals. Those who believe in veganarchy can be either against reform for animals or for it, although do not limit goals to changes within the law.

Layla Abdel Rahim

Layla AbdelRahim is a Canadian anthropologist and author. Her work critiques civilization, technologies, and, what she calls a "predatory anthropology". In Children's Literature, Domestication, and Social Foundation: Narratives of Civilization and Wilderness (2015), she attributes the Holocene extinction and climate change to the human choice of hunting as a cultural choice for subsistence. This anthropological revolution in human self-construction as predator, she argues, generated the need for developing the technologies that would ensure the propagation of a predatory culture and violence. "The first of these technologies is ... the technology of absence. ... This entails physical and emotional absence, but also includes a metaphysical dimension, since technological development is literally linked to death. Namely, the rise of hunting, i.e. killing of others for food, during the Upper Palaeolithic period in the Middle East led some human groups to develop hunting technologies". She cites palaeoanthropologist Clive Gamble who connects this development in hunting technologies to colonization and the work of anthropologist Richard Lee (1988) who links the appearance of human language to the rise in hunting activities during that period. AbdelRahim concludes that hunting "thus led to domestication, and both of these cultures of subsistence kill intentionally and on a systematic basis". Civilization with its cultural, political, and social institutions that classify living beings for the purpose of exploitation, she says, is the material manifestation of this cultural choice and anthropology.Wild Children – Domesticated Dreams: Civilization and the Birth of Education (2013) argues that civilized child rearing cultures are based on the principles of animal domestication. The institutions of education are responsible for the generation of the epistemology of predation and for the propagation of its ideology through scientific texts, pedagogical methods, and fictional narratives.

Total liberation

Total liberationism is a form of green anarchism that combines an opposition to all forms of human oppression with a commitment to animal and earth liberation. Whilst more conventional approaches to anarchist politics typically maintain a tacit assumption of anthropocentrism, proponents of total liberation espouse a holistic revolutionary strategy aimed at identifying the intersections between all forms of domination and social hierarchy, and building alliances between individual political movements in order to integrate them into a single movement aimed at abolishing a range of social structures such as the state, capitalism, patriarchy, racism, heterosexism, cissexism, disablism, ageism, speciesism, and ecological domination. As David Pellow summarises:The concept of total liberation stems from a determination to understand and combat all forms of inequality and oppression. I propose that it comprises four pillars: (1) an ethic of justice and anti-oppression inclusive of humans, nonhuman animals, and ecosystems; (2) anarchism; (3) anti-capitalism; and (4) an embrace of direct action tactics.

Derrick Jensen

Derrick Jensen is an American author and environmental activist (and critic of mainstream environmentalism) living in Crescent City, California. Jensen's work is sometimes characterized as anarcho-primitivist, although he has categorically rejected that label, describing primitivist as a "racist way to describe indigenous peoples." He prefers to be called "indigenist" or an "ally to the indigenous," because "indigenous peoples have had the only sustainable human social organizations, and ... we need to recognize that we [colonizers] are all living on stolen land."A Language Older Than Words uses the lens of domestic violence to look at the larger violence of western culture. The Culture of Make Believe begins by exploring racism and misogyny and moves to examine how this culture's economic system leads inevitably to hatred and atrocity. Strangely Like War is about deforestation. Walking on Water is about education (It begins: "As is true for most people I know, I've always loved learning. As is also true for most people I know, I always hated school. Why is that?"). Welcome to the Machine is about surveillance, and more broadly about science and what he perceives to be a Western obsession with control. Resistance Against Empire consists of interviews with J. W. Smith (on poverty), Kevin Bales (on slavery), Anuradha Mittal (on hunger), Juliet Schor ('globalization' and environmental degradation), Ramsey Clark (on US 'defense'), Stephen Schwartz (editor of The Nonproliferation Review, on nukes), Alfred McCoy (politics and heroin), Christian Parenti (the US prison system), Katherine Albrecht (on RFID), and Robert McChesney (on (freedom of) the media) conducted between 1999 and 2004. Endgame is about what he describes as the inherent unsustainability of civilization. In this book he asks: "Do you believe that this culture will undergo a voluntary transformation to a sane and sustainable way of living?" Nearly everyone he talks to says no. His next question is: "How would this understanding — that this culture will not voluntarily stop destroying the natural world, eliminating indigenous cultures, exploiting the poor, and killing those who resist — shift our strategy and tactics? The answer? Nobody knows, because we never talk about it: we're too busy pretending the culture will undergo a magical transformation." Endgame, he says, is "about that shift in strategy, and in tactics." Jensen co-wrote the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet with Lierre Keith and Aric McBay

CrimethInc.

CrimethInc. is a decentralized anarchist collective of autonomous cells. CrimethInc. emerged in the mid-1990s, initially as the hardcore zine Inside Front, and began operating as a collective in 1996. It has since published widely read articles and zines for the anarchist movement and distributed posters and books of its own publication. Individuals adopting the CrimethInc. nom de guerre have included convicted ELF arsonists, as well as hacktivists who successfully attacked the websites of DARE, Republican National Committee and sites related to U.S. President George W. Bush's 2004 re-election campaign. The creation of propaganda has been described as the collectives' core function. Among their best-known publications are the books Days of War, Nights of Love, Expect Resistance, Evasion, Recipes for Disaster: An Anarchist Cookbook and the pamphlet Fighting For Our Lives (of which, to date, they claim to have printed 600,000 copies), the hardcore punk/political zine Inside Front, and the music of hardcore punk bands. As well as the traditional anarchist opposition to the state and capitalism, agents have, at times, advocated a straight edge lifestyle, the total supersession of gender roles, violent insurrection against the state, and the refusal of work.Direct action

Some green anarchists engage in direct action (not to be confused with ecoterrorism). Organizing themselves through groups like Earth First!, Root Force, or more drastically the Earth Liberation Front ELF, Earth Liberation Army (ELA) and Animal Liberation Front (ALF). They may take direct action against what they see as systems of oppression, such as the logging industry, the meat and dairy industries, animal testing laboratories, genetic engineering facilities and, more rarely, government institutions.Such actions are usually, though not always, non-violent, with groups such as The Olga Cell attempting assassinations of nuclear scientists, and other related groups sending letterbombs to nano tech and nuclear tech-related targets. Though not necessarily Green anarchists, activists have used the names Animal Rights Militia, Justice Department and Revolutionary Cells among others, to claim responsibility for openly violent attacks.

Convictions

Rod Coronado is an eco-anarchist and is an unofficial spokesperson for the Animal Liberation Front and Earth Liberation Front. On February 28, 1992, Coronado carried out an arson attack on research facilities at Michigan State University (MSU), and released mink from a nearby research farm on campus, an action claimed by the ALF, and for which Coronado was subsequently convicted.In 1997, the editors of Green Anarchist magazine and two British supporters of the Animal Liberation Front were tried in connection with conspiracy to incite violence, in what came to be known as the GANDALF trial.

Green anarchist Tre Arrow was sought by the FBI in connection with an ELF arson on April 15, 2001 at Ross Island Sand and Gravel in Portland, torching three trucks amounting of $200,000 in damage. Another arson occurred a month later at Ray Schoppert Logging Company in Estacada, Oregon, on June 1, 2001 against logging trucks and a front loader, resulting in $50,000 damage. Arrow was indicted by a federal grand jury in Oregon and charged with four felonies for this crime on October 18, 2002. On March 13, 2004, after fleeing to British Columbia, he was arrested in Victoria for stealing bolt cutters and was also charged with being in Canada illegally. He was then sentenced on August 12, 2008 to 78 months in federal prison for his part in the arson and conspiracy ELF attacks in 2001.

In January 2006, Eric McDavid, a green anarchist, was convicted of conspiring to use fire or explosives to damage corporate and government property. On March 8, he formally declared a hunger strike due to the jail refusing to provide him with vegan food. He has been given vegan food off and on since. In September 2007, he was convicted on all counts after the two activists he conspired with pleaded guilty testified against him. An FBI confidential source named "Anna" was revealed as a fourth participant, in what McDavid's defense argued was entrapment. In May 2008, he was sentenced to nearly 20 years in prison.

On March 3, 2006, a federal jury in Trenton, New Jersey convicted six members of SHAC, including green-anarchist Joshua Harper, for "terrorism and Internet stalking", according to the New York Times, finding them guilty of using their website to "incite attacks" on those who did business with Huntingdon Life Sciences HLS. In September 2006, the SHAC 7 received jail sentences of 3 to 6 years.

- Other prisoners:

- Marco Camenisch: Swiss green anarchist accused of arson against electricity pylon;

- Nicole Vosper: green anarchist who pleaded guilty to charges against HLS;

- Marius Mason (born Marie Jeanette Mason): serving 21 years and 10 months (#04672-061, FMC Carswell, Federal Medical Center, P.O. Box 27137, Fort Worth, TX 76127, USA) for his involvement in an ELF arson against a University building carrying out Genetically Modified crop tests. Marius also pleaded guilty to conspiring to carry out ELF actions and admitted involvement in 12 other ELF actions. (vegan).