From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Biosphere 2 is an American

Earth system science research facility located in

Oracle, Arizona. It has been owned by the

University of Arizona since 2011. Its mission is to serve as a center for research, outreach, teaching, and

lifelong learning about Earth, its living systems, and its place in the universe. It is a 3.14-acre (1.27-hectare) structure originally built to be an

artificial, materially closed ecological system, or

vivarium. It remains the largest closed system ever created.

Biosphere 2 was originally meant to demonstrate the viability of

closed ecological systems to support and maintain human life in outer

space.

It was designed to explore the web of interactions within life systems

in a structure with different areas based on various biological

biomes.

In addition to the several biomes and living quarters for people,

there was an agricultural area and work space to study the interactions

between humans, farming, technology and the rest of nature as a new kind

of laboratory for the study of the global ecology. Its mission was a

two-year closure experiment with a crew of eight humans

("biospherians"). Long-term it was seen as a precursor to gain knowledge about the use of closed biospheres in

space colonization.

As an experimental ecological facility it allowed the study and

manipulation of a mini biospheric system without harming Earth's

biosphere. Its seven biome areas were a 1,900-square-meter

(20,000 sq ft)

rainforest, an 850-square-meter (9,100 sq ft)

ocean with a

coral reef, a 450-square-meter (4,800 sq ft)

mangrove wetlands, a 1,300-square-metre (14,000 sq ft)

savannah grassland, a 1,400-square-meter (15,000 sq ft)

fog desert, and two anthropogenic biomes: a 2,500-square-meter (27,000 sq ft)

agricultural system and a human

habitat

with living spaces, laboratories and workshops. Below ground was an

extensive part of the technical infrastructure. Heating and cooling

water circulated through independent piping systems and

passive solar input through the glass

space frame panels covering most of the facility, and

electrical power was supplied into Biosphere 2 from an onsite natural gas energy center.

Biosphere 2 was only used twice for its original intended

purposes as a closed-system experiment: once from 1991 to 1993, and the

second time from March to September 1994. Both attempts, though heavily

publicized, ran into problems including low amounts of food and oxygen,

die-offs of many animals and plants included in the experiment (though

this was anticipated since the project used a strategy of deliberately

"species-packing" anticipating losses as the biomes developed), group

dynamic tensions among the resident crew, outside politics and a power

struggle over management and direction of the project. Nevertheless, the

closure experiments set world records in closed ecological systems,

agricultural production, health improvements with the high nutrient and

low caloric diet the crew followed, and insights into the

self-organization of complex biomic systems and atmospheric dynamics. The second closure experiment achieved total food sufficiency and did not require injection of oxygen.

In June 1994, during the middle of the second experiment, the

managing company, Space Biosphere Ventures, was dissolved, and the

facility was left in limbo. Columbia University assumed management of

the facility in 1995 and used it to run experiments until 2003. It then

looked in danger of being demolished to make way for housing and retail

stores, but was taken over for research by the University of Arizona in

2007. The University of Arizona took full ownership of the structure in

2011.

Planning and construction

Biosphere

2 was originally constructed between 1987 and 1991 by Space Biosphere

Ventures, a joint venture whose principal officers were

John P. Allen,

inventor and executive chairman; Margaret Augustine, CEO; Marie

Harding, vice-president of finance; Abigail Alling, vice president of

research; Mark Nelson, director of space and environmental applications,

William F. Dempster, director of system engineering, and Norberto

Alvarez-Romo, vice president of mission control. Project funding came

primarily from the joint venture's financial partner,

Ed Bass's Decisions Investment. The project cost US$200 million from 1985 to 2007.

It was named "Biosphere 2" because it was meant to be the second fully self-sufficient

biosphere, after the Earth itself.

Location

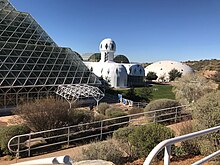

Biosphere 2 sits on a sprawling 40-acre (16-hectare) science campus that is open to the public

Exterior showing parts of the rainforest biome and of the habitat, with the West lung in the background.

Engineering

Biosphere 2, view from the thornscrub, a transition zone between Savannah and Desert (foreground) and Ocean (background) sections.

The tropical rainforest biome in February, 2017

The above-ground physical structure of Biosphere 2 was made of steel

tubing and high-performance glass and steel frames. The frame and

glazing materials were designed and made to specification by a firm run

by a one-time associate of

Buckminster Fuller, Peter Jon Pearce (Pearce Structures, Inc.).

The window seals and structures had to be designed to be almost

perfectly airtight, such that the air exchange would be extremely low,

permitting tracking of subtle changes over time. The patented airtight

sealing methods, developed by Pearce and William Dempster, achieved a

remarkable leak rate of less than 10% per year. Without such tight

closure, the slow decline of oxygen which occurred at a rate of less

than 1/4% per month during the first two-year closure experiment might

not have been observed.

During the day, the heat from the sun caused the air inside to

expand and during the night it cooled and contracted. To avoid having to

deal with the huge forces that maintaining a constant volume would

create, the structure had large diaphragms kept in domes called "lungs"

or variable volume structures.

Since opening a window was not an option, the structure also

required a sophisticated system to regulate temperatures within desired

parameters, which varied for the different biomic areas. Though cooling

was the largest energy need, heating had to be supplied in the winter

and closed loop pipes and air handlers were key parts of the energy

system. An energy center on site provided electricity and heated and

cooled water, employing natural gas and backup generators, ammonia

chillers and water cooling towers.

First mission

The first closed mission lasted from September 26, 1991 to September 26, 1993. The crew were: medical doctor and researcher

Roy Walford,

Jane Poynter,

Taber MacCallum,

Mark Nelson, Sally Silverstone, Abigail Alling, Mark Van Thillo, and Linda Leigh.

The agricultural system produced 83% of the total diet, which

included crops of bananas, papayas, sweet potatoes, beets, peanuts,

lablab and

cowpea beans, rice, and wheat.

No toxic chemicals could be used, since they would impact health and

water and nutrients were recycled back into the farm soils. Especially

during the first year the eight inhabitants reported continual hunger.

Calculations indicated that Biosphere 2's farm was amongst the highest

producing in the world "exceeding by more than five times that of the

most efficient agrarian communities of Indonesia, southern China, and

Bangladesh.”

They consumed the same low-calorie, nutrient-dense diet which Roy Walford had studied in his research on

extending lifespan through diet.

Medical markers indicated the health of the crew during the two years

was excellent. They showed the same improvement in health indices such

as lowering of blood cholesterol, blood pressure, enhancement of immune

system. They lost an average of 16% of their pre-entry body weight

before stabilizing and regaining some weight during their second year. Subsequent studies showed that the biospherians'

metabolism became more efficient at extracting nutrients from their food as an adaptation to the low-calorie, high nutrient diet.

"The overall health of the biospherians crews inside Biosphere 2

confirm that the original design of the Biosphere 2 technosphere systems

did avoid a buildup of toxins, and the bioregenerative technologies and

life systems inside Biosphere 2 maintained a healthy environment."

Some of the domestic animals that were included in the agricultural area during the first mission included four African

pygmy goats and one billy goat, 35 hens and three roosters (a mix of Indian jungle fowl (

Gallus gallus),

Japanese silky bantam, and a hybrid of these), two sows and one boar Ossabaw dwarf pigs, as well as

tilapia fish grown in a rice and

azolla pond system originating millennia ago in China.

A strategy of "species-packing" was practiced to ensure that food

webs and ecological function could be maintained if some species did

not survive. The

fog desert area became more

chaparral

in character due to condensation from the space frame. The savannah was

seasonally active; its biomass was cut and stored by the crew as part

of their management of carbon dioxide. Rainforest

pioneer species grew rapidly, but trees there and in the savannah suffered from

etiolation and weakness caused by lack of

stress wood, normally created in response to winds in natural conditions.

Corals

reproduced in the ocean area, and crew helped maintain ocean system

health by hand-harvesting algae from the corals, manipulating calcium

carbonate and pH levels to prevent the ocean becoming too acidic, and by

installing an improved

protein skimmer to supplement the algae turf

scrubber system originally installed to remove excess nutrients. The mangrove area developed rapidly but with less

understory than a typical

wetland possibly because of reduced light levels.

Nevertheless, it was judged to be a successful analogue to the

Everglades area of Florida where the mangroves and marsh plants were

collected.

Biosphere 2 because of its small size and buffers, concentration

of organic materials and life, had greater fluctuations and more rapid

biogeochemical cycles than are found in Earth's biosphere. Most of the introduced

vertebrate species and virtually all of the

pollinating insects died, though there was reproduction of plants and animals. Insect pests, like

cockroaches, flourished. Many insects had been included in original species mixes in the biomes but a globally invasive tramp ant species,

Paratrechina longicornis, unintentionally sealed in, had come to dominate other ant species.

The planned ecological succession in the rainforest and strategies to

protect the area from harsh incident sunlight and salt aerosols from the

ocean worked well, and a surprising amount of the original biodiversity

persisted. Biosphere 2 in its early ecological development was likened to an island ecology.

Group dynamics: psychology, conflict, and cooperation

View of part of the crew dining room, serving counter from kitchen and stairway up to an entertainment area.

The crew's kitchen as it originally looked during the first mission.

Much of the evidence for isolated human groups comes from psychological studies of scientists overwintering in

Antarctic research stations. The study of this phenomenon is "confined environment psychology", and according to Jane Poynter it was known to be a challenge and often crews split into factions.

Before the first closure mission was half over, the group had

split into two factions and, according to Poynter, people who had been

intimate friends had become implacable enemies, barely on speaking

terms.

Others point out that the crew continued to work together as a team to

achieve the experiment's goals, mindful that any action that harmed

Biosphere 2 might imperil their own health. This is in contrast to other

expeditions where internal frictions can lead to unconscious sabotage

of each other and the overall mission. All of the crew felt a very

strong and visceral bond with their living world.

They kept air and water quality, atmospheric dynamics and health of the

life systems constantly in their attention in a very visceral and

profound way. This intimate “metabolic connection” enabled the crew to

discern and respond to even subtle changes in the living systems.

(Alling et al., 2002; Alling and Nelson, 1993). "Appreciation of the

value of biosphere interconnectedness and interdependency was

appreciated as both an everyday beauty and a challenging reality",

Walford later acknowledged "I don't like some of them, but we were a

hell of a team. That was the nature of the factionalism... but despite

that, we ran the damn thing and we cooperated totally".

The factions inside the bubble formed from a rift and power

struggle between the joint venture partners on how the science should

proceed, as biospherics or as specialist ecosystem studies (perceived as

reductionist). The faction that included Poynter felt strongly that

increasing research should be prioritized over degree of closure. The

other faction backed project management and the overall mission

objectives. On February 14, a portion of the Scientific Advisory

Committee (SAC) resigned.

Time Magazine

wrote: "Now, the veneer of credibility, already bruised by allegations

of tamper-prone data, secret food caches and smuggled supplies, has

cracked ... the two-year experiment in self-sufficiency is starting to

look less like science and more like a $150 million stunt".

In fact, the SAC was dissolved because it had deviated from its mandate

to review and improve scientific research and became involved in

advocating management changes. A majority of the SAC members chose to

remain as consultants to Biosphere 2. The SAC's recommendations in their

report were implemented including a new Director of Research [Dr. Jack

Corliss], allowing import/export of scientific samples and equipment

through the facility airlocks to increase research and decrease crew

labor, and to generate a formal research program. Some sixty-four

projects were included in the research program that Walford and Alling

spearheaded developing.

Undoubtedly the lack of oxygen and the calorie-restricted, nutrient-dense diet contributed to low morale.

The Alling faction feared that the Poynter group were prepared to go so

far as to import food, if it meant making them fitter to carry out

research projects. They considered that would be a project failure by

definition.

In November 1992, the hungry Biospherians began eating seed stocks that had not been grown inside the Biosphere 2. Poynter made Chris Helms,

PR

Director for the enterprise, aware of this. She was promptly dismissed

by Margret Augustine, CEO of Space Biospheres Ventures, and told to come

out of the biosphere. This order was, however, never carried out.

Poynter writes

that she simply decided to stay put, correctly reasoning that the order

could not be enforced without effectively terminating the closure.

Isolated groups tend to attach greater significance to group

dynamic and personal emotional fluctuations common in all groups. Some

reports from polar station crews exaggerated psychological problems.

So, although some of the first closure team thought they were

depressed, psychological examination of the biospherians showed no

depression and fit the explorer/adventurer profile, with both women and

men testing very similar to astronauts.

One of the psychologists noted, "If I was lost in the Amazon and was

looking for a guide to get out, and to survive with, then [the

biospherian crew] would be top choices."

Challenges

Among

the problems and miscalculations encountered in the first mission were

unanticipated condensation making the "desert" too wet, population

explosions of greenhouse ants and cockroaches, morning glories

overgrowing the rainforest area, blocking out other plants and less

sunlight (40-50% of outside light) entering the facility than originally

anticipated. Biospherians intervened to control invasive plants when

needed to preserve biodiversity, functioning as "

keystone predators".

In addition, construction itself was a challenge; for example, it was

difficult to manipulate the bodies of water to have waves and tidal

changes.

Engineers came up with innovative solutions to supplement natural

functions the Earth's biosphere normally performs, e.g. vacuum pumps to

create gentle waves in the ocean without endangering marine biota,

sophisticated heating and cooling systems. All the technology was

selected to minimize outgassing and discharge of harmful substances

which might damage Biosphere 2's life.

There was controversy when the public learned that the project

had allowed an injured member to leave and return, carrying new material

inside. The team claimed the only new supplies brought in were plastic

bags, but others accused them of bringing food and other items. More

criticism was raised when it was learned that, likewise, the project

injected oxygen in January 1993 to make up for a failure in the balance

of the system that resulted in the amount of oxygen steadily declining.

Some thought that these criticisms ignored that Biosphere 2 was an

experiment where the unexpected would occur, adding to knowledge of how

complex ecologies develop and interact, not a demonstration where

everything was known in advance.

H.T. Odum noted: “The management process during 1992-1993 using data to

develop theory, test it with simulation, and apply corrective actions

was in the best scientific tradition. Yet some journalists crucified the

management in the public press, treating the project as if it was an

Olympic contest to see how much could be done without opening the

doors”.

The

oxygen

inside the facility, which began at 20.9%, fell at a steady pace and

after 16 months was down to 14.5%. This is equivalent to the oxygen

availability at an elevation of 4,080 meters (13,400 ft). Since some biospherians were starting to have

symptoms like

sleep apnea

and fatigue, Walford and the medical team decided to boost oxygen with

injections in January and August 1993. The oxygen decline and minimal

response of the crew indicated that changes in air pressure are what

trigger human adaptation responses. These studies enhanced the

biomedical research program.

Managing CO

2 levels was a particular challenge, and a

source of controversy regarding the Biosphere 2 project's alleged

misrepresentation to the public. Daily fluctuation of

carbon dioxide dynamics was typically 600 ppm because of the strong drawdown during sunlight hours by plant

photosynthesis, followed by a similar rise during the nighttime when system

respiration dominated. As expected, there was also a strong seasonal signature to CO

2

levels, with wintertime levels as high as 4,000-4,500 ppm and

summertime levels near 1,000 ppm. The crew worked to manage the CO

2 by occasionally turning on a

CO2 scrubber,

activating and de-activating the desert and savannah through control of

irrigation water, cutting and storing biomass to sequester carbon, and

utilizing all potential planting areas with fast-growing species to

increase system photosynthesis. In November 1991, investigative reporting in the

Village Voice alleged that the crew had secretly installed the CO

2 scrubber device, and claimed that this violated Biosphere 2's advertised goal of recycling all materials naturally.

Others pointed out there was nothing secret about the carbon dioxide

device and it constituted another technical system augmenting ecological

processes. The carbon precipitator could reverse the chemical reactions

and thus release the stored carbon dioxide in later years when the

facility might need additional carbon.

Many suspected the drop in oxygen was due to

microbes in the soil.

The soils were selected to have enough carbon to provide for the plants

of the ecosystems to grow from infancy to maturity, a plant mass

increase of perhaps 20 tons (18,000 kg).

The release rate of that soil carbon as carbon dioxide by respiration

of soil microbes was an unknown that the Biosphere 2 experiment was

designed to reveal. Subsequent research showed that Biosphere 2's farm

soils had reached a more stable ratio of carbon and nitrogen, lowering

the rate of CO

2 release, by 1998.

The respiration rate was faster than the photosynthesis (possibly

in part due to relatively low light penetration through the glazed

structure and the fact that Biosphere 2 started with a small but rapidly

increasing plant biomass) resulting in a slow decrease of oxygen. A

mystery accompanied the oxygen decline: the corresponding increase in

carbon dioxide did not appear. This concealed the underlying process

until an investigation by Jeff Severinghaus and

Wallace Broecker of Columbia University's

Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory using isotopic analysis showed that carbon dioxide was reacting with exposed concrete inside Biosphere 2 to form

calcium carbonate, thereby sequestering both carbon and oxygen.

Second mission

During

the transition period between missions, extensive research and system

improvements had been undertaken. Concrete was sealed to prevent uptake

of carbon dioxide. The second mission began on March 6, 1994, with an

announced run of ten months. The crew was Norberto Alvarez-Romo (Capt.),

John Druitt, Matt Finn, Pascale Maslin, Charlotte Godfrey, Rodrigo Romo

and Tilak Mahato. The second crew achieved complete sufficiency in food

production.

On April 1, 1994 a severe dispute within the management team led to the ousting of the on-site management by

federal marshals serving a restraining order, and financier

Ed Bass hired

Stephen Bannon, manager of the

Bannon & Co. investment banking team from Beverly Hills, California, to run Space Biospheres Ventures.

Some biospherians and staff were concerned about Bannon, who had

previously investigated cost overruns at the site. Two former Biosphere 2

crew members flew back to Arizona to protest the hire and broke into

the compound to warn current crew members that Bannon and the new

management would jeopardize their safety.

At 3 am on April 5, 1994, Abigail Alling and Mark Van Thillo,

members of the first crew, allegedly vandalized the project from

outside,

opening one double-airlock door and three single door emergency exits,

leaving them open for approximately fifteen minutes. Five panes of

glass were also broken. Alling later told the

Chicago Tribune that she "considered the Biosphere to be in an emergency state... In no way was it sabotage. It was my responsibility." About 10% of the biosphere's air was exchanged with the outside during this time, according to systems analyst

Donella Meadows,

who received a communication from Ms. Alling in which she explained

that she and Van Thillo judged it their ethical duty to give those

inside the choice of continuing with the drastically changed human

experiment or leaving, as they didn't know what the crew had been told

of the new situation. “On April 1, 1994, at approximately 10 AM …

limousines arrived on the biosphere site … with two investment bankers

hired by Mr. Bass … They arrived with a temporary restraining order to

take over direct control of the project … With them were 6-8 police

officers hired by the Bass organization … They immediately changed locks

on the offices … All communication systems were changed (telephone and

access codes), and [we] were prevented from receiving any data regarding

safety, operations, and research of Biosphere 2.” Alling emphasized

several times in her letter that the “bankers” who suddenly took over

“knew nothing technically or scientifically, and little about the

biospherian crew.”

Four days later, the captain Norberto Alvarez-Romo (by then

married to Biosphere 2 chief executive Margaret Augustine) precipitously

left the Biosphere for a "family emergency" after his wife's

suspension.

He was replaced by Bernd Zabel, who had been nominated as captain of

the first mission but who was replaced at the last minute. Two months

later, Matt Smith replaced Matt Finn.

The ownership and management company Space Biospheres Ventures

was officially dissolved on June 1, 1994. This left the scientific and

business management of the mission to the interim turnaround team, who

had been contracted by the financial partner, Decisions Investment Co.

Mission 2 was ended prematurely on September 6, 1994. No further

total system science has emerged from Biosphere 2 as the facility was

changed by Columbia University from a closed ecological system to a

"flow-through" system where CO2 could be manipulated at desired levels.

Steve Bannon

left Biosphere 2 after two years, but his departure was marked by a

civil lawsuit filed against Space Biosphere Ventures by the former crew

members who had broken in.

During a 1996 trial, Bannon testified that he had called one of the

plaintiffs, Abigail Alling, a "self-centered, deluded young woman" and a

"bimbo."

He also testified that when the woman submitted a five-page complaint

outlining safety problems at the site, he promised to shove the

complaint "down her fucking throat." Bannon attributed this to "hard

feelings and broken dreams."

At the end of the trial, the jury found for the plaintiffs and ordered

Space Biosphere Ventures to pay them $600,000, but also ordered the

plaintiffs to pay the company $40,089 for the damage they had caused. Some

have observed that Bannon orchestrated the hostile take-over and

destruction of Biosphere 2 as a revolutionary total system global

ecology laboratory, not because of any interest in ecological science.

Science

A

special issue of the Ecological Engineering journal edited by Marino and

Howard T. Odum (1999), published as "Biosphere 2: Research Past and

Present" (Elsevier, 1999) represents the most comprehensive assemblage

of collected papers and findings from Biosphere 2. The papers range from

calibrated models that describe the system metabolism, hydrologic

balance, and heat and humidity, to papers that describe rainforest,

mangrove, ocean, and agronomic system development in this carbon

dioxide-rich environment.

Though several dissertations and many scientific papers used data from

the early closure experiments at Biosphere 2, much of the original data

has never been analyzed and is unavailable or lost, perhaps due to

scientific politics and in-fighting.

Some of the controversy at Biosphere 2 stemmed from the

long-standing division in science between analytic, reductionist science

and integrative, holistic science.

Rebecca Reider expanded her history of science thesis at Harvard

into a book on Biosphere 2. She noted that because Biosphere 2's

creators were perceived as outsiders to academic science, the project

was scrutinized but sometimes poorly understood in the media. She noted

that Biosphere 2 broke a number of unspoken taboos: “’Science’ could be

performed only by official scientists, only the right high priests could

interpret nature for everyone else….’Science’ was separate from art

(and the thinking mind was separate from the emotional heart)…’Science’

required some neat intellectual boundary between humans and nature; it

did not necessarily involve humans learning to live with the world

around them. Finally, ‘science’ must follow a specific method: think up a

hypothesis, test it and get some numbers to prove you were right”.

After Columbia University assumed management, the scrutiny ceased

because it was assumed they were "proper" scientists.

The dichotomy is a false one as there are many valid approaches

to science. John Allen, the inventor of Biosphere 2, wrote: “Four basic

ways uneasily co-exist in science to deal with understanding complex

systems: [1] prolonged naturalist observation, description of observed

regularities and classification of parts… [2] analyzing component parts

of the object of study, formulating restricted hypotheses, and then,

holding all else other than the chosen part as constant as possible,

measure changes produced by measured impacts...[3] accept complexity as

an irreducible element, and then to search for the organized structure

that enables us to examine the entity as a whole, to ascertain its

specific laws or regularities…[4] Put into an operating model a

synthesis of these three approaches, together with test principles of

engineering, to test the validity of the existent thinking’s predictive

powers, and to provide a fecund base for new observations. This full

interplay of observation, analysis and structuring to make a working

apparatus in order to test and extend our knowledge of biospherics is

the approach we used to create Biosphere 2. This interplay of all four

scientific approaches is required to study Earth’s biosphere, the most

complex entity yet encountered.”

Praise and criticism

One view of Biosphere 2 was that it was "the most exciting scientific project to be undertaken in the U.S. since President

John F. Kennedy launched us toward the moon". Others called it "

New Age drivel masquerading as science". John Allen and Roy Walford did have mainstream credentials.

John Allen

held a degree in Metallurgical-Mining Engineering from the Colorado

School of Mines, and an MBA from the Harvard Business School.

Roy Walford received his doctorate of medicine from the University of

Chicago and taught at UCLA as a Professor of Pathology for 35 years.

Mark Nelson obtained his Ph.D. in 1998 under Professor

H.T. Odum in ecological engineering further developing the constructed wetlands used to treat and recycle sewage in Biosphere 2, to coral reef protection along the Yucatán coast where the corals were collected. Linda Leigh obtained her PhD with a dissertation on biodiversity and the Biosphere 2 rainforest working with Odum.

Abigail Alling, Mark van Thillo and Sally Silverstone helped start the

Biosphere Foundation where they worked on coral reef and marine

conservation and sustainable agricultural systems.

Jane Poynter and Taber MacCallum co-founded Paragon Space Development

Corporation which has studied the first mini-closed system and the first

full animal life cycle in space and assisted in setting world records

in high altitude descents.

Questioning the credentials of the participants (despite the

contribution in the preparation phase of Biosphere 2 of worldwide

top-level scientists and among others the

Russian Academy of Sciences),

Marc Cooper wrote that "the group that built, conceived, and directs

the Biosphere project is not a group of high-tech researchers on the

cutting edge of science but a clique of recycled theater performers that

evolved out of an authoritarian—and decidedly

non-scientific—personality cult". He was referring to the

Synergia Ranch in

New Mexico,

where indeed many of the Biospherians did practice theater under John

Allen's leadership, and began to develop the ideas behind Biosphere 2. They also founded the Institute of Ecotechnics

and began innovative field projects in challenging biomes to advance

the healthy integration of human technologies and the environment where

many of the biospherian candidates gained experience in operating

real-time complex projects.

One of their own scientific consultants was earlier critical. Dr.

Ghillean Prance, director of the

Royal Botanical Gardens in

Kew, designed the rainforest

biome

inside the Biosphere. Although he later changed his opinion,

acknowledging the unique scope of this experiment and contributed to its

success as a consultant, in a 1983 interview (8 years before the start

of the experiment), Prance said, "I was attracted to the

Institute of Ecotechnics

because funds for research were being cut and the institute seemed to

have a lot of money which it was willing to spend freely. Along with

others, I was ill-used. Their interest in science is not genuine. They

seem to have some sort of secret agenda, they seem to be guided by some

sort of religious or philosophical system." Prance went on in the 1991

newspaper interview to say "they are visionaries.,.And maybe to fulfill

their vision they have become somewhat cultlike. But they are not a

cult, per se....I am interested in ecological restoration systems. And I

think all sorts of scientific things can come of this experiment, far

beyond the space goal... When they came to me with this new project,

they seemed so well organized, so inspired, I simply decided to forget

the past. You shouldn't hold their past against them."

Poynter in her memoir rebuts the critique that because some of

the creative team of Biosphere 2 weren't highly credentialed scientists,

that that ad hominem argument invalidates the results of the endeavor.

"“Some reporters hurled accusations that we were unscientific.

Apparently because many of the SBV managers were not themselves degreed

scientists, this called into question the entire validity of the

project, even though some of the world’s best scientists were working

vigorously on the project’s design and operation. The critique was not

fair. Since leaving Biosphere 2, I have run a small business for ten

years that sent experiments on the shuttle and to the space station, and

is designing life support systems for the replacement shuttle and

future moon base. I do not have a degree, not even an MBA from Harvard,

as John [Allen] had. I hire scientists and top engineers. Our company’s

credibility is not called into question because of my credentials: we

are judged on the quality of our work”.

H.T. Odum noted that mavericks, outsiders have often contributed to the

development of science: “The original management of Biosphere 2 was

regarded by many scientists as untrained for lack of scientific degrees,

even though they had engaged in a preparatory study program for a

decade, interacting with the international community of scientists

including the Russians involved with closed systems. The history of

science has many examples where people of atypical background open

science in new directions, in this case implementing mesocosm

organization and ecological engineering with fresh hypotheses”.

The Biosphere 2 Science Advisory Committee, chaired by Tom

Lovejoy of the Smithsonian Institution, in its report of August 1992

reported: "The committee is in agreement that the conception and

construction of Biosphere 2 were acts of vision and courage. The scale

of Biosphere 2 is unique and Biosphere 2 is already providing unexpected

scientific results not possible through other means (notably the

documented, unexpected decline in atmospheric oxygen levels.) Biosphere 2

will make important scientific contributions in the fields of

biogeochemical cycling, the ecology of closed ecological systems, and

restoration ecology." Columbia University assembled outside scientists

to evaluate the potential of the facility after they took over

management, and concluded the following: "A group of world-class

scientists got together and decided the Biosphere 2 facility is an

exceptional laboratory for addressing critical questions relative to the

future of Earth and its environment."

Columbia University

In December 1995 the Biosphere 2 owners transferred management to

Columbia University of New York City which embarked on a successful eight-year run at the Biosphere 2 campus. Columbia ran Biosphere 2 as a research site and campus until 2003. Subsequently, management reverted to the owners.

In 1996, Columbia University changed the virtually airtight,

materially closed structure designed for closed system research, to a

"flow-through" system, and halted closed system research. They

manipulated carbon dioxide levels for

global warming research, and injected desired amounts of carbon dioxide, venting as needed.

During Columbia's tenure, students from Columbia and other colleges and

universities would often spend one semester at the site.

Important research during Columbia's tenure demonstrated the

devastating impacts on coral reefs from elevated atmospheric CO2 and

acidification that will result from continued global climate change.

Frank Press, former president of the National Academy of Sciences,

described these interactions between atmosphere and ocean, taking

advantage of the highly controllable ocean mesocosm of Biosphere 2, as

the “first unequivocal experimental confirmation of the human impact on

the planet”.

Studies in Biosphere 2’s terrestrial biomes showed that a

saturation point was reached with elevated CO2 beyond which they are

unable to uptake more. The studies' authors noted that the striking

differences between the Biosphere 2 rainforest and desert biomes in

their whole system responses “illustrates the importance of large-scale

experimental research in the study of complex global change issues".

Site sold

In

January 2005, Decisions Investments Corporation, owner of Biosphere 2,

announced that the project's 1,600-acre (650 ha) campus was for sale.

They preferred a research use to be found for the complex but were not

excluding buyers with different intentions, such as big universities,

churches, resorts, and spas.

In June 2007 the site was sold for $50 million to CDO Ranching &

Development, L.P. 1,500 houses and a resort hotel were planned, but the

main structure was still to be available for research and educational

use.

Acquisition by University of Arizona

On June 26, 2007, the

University of Arizona

announced it would take over research at the Biosphere 2. The

announcement ended fears that the structure would be demolished.

University officials said private gifts and grants enabled them to cover

research and operating costs for three years with the possibility of

extending funding for ten years.

It was extended for ten years, and is now engaged in research projects

including research into the terrestrial water cycle and how it relates

to ecology, atmospheric science, soil geochemistry, and climate change.

In June 2011, the university announced that it would assume full

ownership of Biosphere 2, effective July 1.

CDO Ranching & Development donated the land, Biosphere buildings

and several other support and administrative buildings. The Philecology

Foundation (a nonprofit research foundation founded by Ed Bass) pledged

US$20 million for the ongoing science and operations.

Current research

There are many small-scale research projects at Biosphere 2, as well as several large-scale research projects including: